Exploring Topics and Genres in Storytime Books: A Text Mining Approach

Soohyung Joo

Associate Professor, School

of Information Science

University of Kentucky

Lexington, Kentucky, United

States of America

Email: soohyung.joo@uky.edu

Erin Ingram

Research Assistant, School

of Information Science

University of Kentucky

Lexington, Kentucky, United

States of America

Email: erin.ingram@uky.edu

Maria Cahill

Associate Professor, School

of Information Science

University of Kentucky

Lexington, Kentucky, United

States of America

Email: maria.cahill@uky.edu

Received: 15 Apr. 2021 Accepted: 14 Oct. 2021

![]() 2021 Joo, Ingram, and Cahill. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2021 Joo, Ingram, and Cahill. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29963

Abstract

Objective

–

While storytime programs for preschool children are offered in nearly all public

libraries in the United States, little is known about the books librarians use

in these programs. This study employed text analysis to explore topics and

genres of books recommended for public library storytime programs.

Methods

–

In the study, the researchers randomly selected 429 children books recommended

for preschool storytime programs. Two corpuses of text were extracted from the

titles, abstracts, and subject terms from bibliographic data. Multiple text

mining methods were employed to investigate the content of the selected books,

including term frequency, bi-gram analysis, topic modeling, and sentiment

analysis.

Results

–

The findings revealed popular topics in storytime books, including

animals/creatures, color, alphabet, nature, movements, families, friends, and

others. The analysis of bibliographic data described various genres and formats

of storytime books, such as juvenile fiction, rhymes, board books, pictorial

work, poetry, folklore, and nonfiction. Sentiment analysis results reveal that

storytime books included a variety of words representing various dimensions of

sentiment.

Conclusion

–

The findings suggested that books recommended for storytime programs are

centered around topics of interest to children that also support school readiness.

In addition to selecting fictionalized stories that will support children in

developing the academic concepts and socio-emotional skills necessary for later

success, librarians should also be mindful of integrating informational texts

into storytime programs.

Introduction

Storytime

programs for preschool children are a common provision of public libraries

worldwide. With a long history (Albright et al., 2009) and the highest rates of

attendance among public library program offerings (Miller et al., 2013),

storytimes serve as the backbone of public library programming. Preschool

storytimes are typically designed to be highly interactive, learning-focused,

thirty-minute enjoyable endeavors that incorporate shared book readings, props,

songs, and activities intended to engage both children and their adult

caregivers (Diamant-Cohen & Hetrick, 2014; Goulding et al., 2017; Mills et

al., 2018).

Book selection

is one task among many that storytime providers undertake when planning a

public library storytime program. Other planning tasks may include deciding on

a theme, incorporating educational tips for caregivers, gathering supplies for

an activity or craft, creating handouts for caregivers, integrating technology

resources, and choosing songs, interactive rhymes, fingerplays, movement

activities, or flannel board activities (Diamont-Cohen

& Hetrick, 2014; Ghoting & Martin-Diaz,

2006). To aid in planning these tasks, storytime providers may rely on

professional resources for storytime development such as conferences, books

published by the American Library Association and other library publishers,

trainings offered through state library agencies and consortia, and webinars or

courses from commercial websites such as Webjunction

or Library Juice Academy. However, these formal resources may not be accessible

to all storytime providers due to financial costs or time constraints.

Therefore, storytime providers at a public library with a limited budget may

prefer to plan with the aid of a free informal, online resource, such as a

librarian’s blog about storytime programs or a library’s website with

recommended reading lists.

In this study,

we explored the subject matter of books recommended by online resources for

public library preschool storytime programs. We extracted bibliographic records

of books recommended for storytimes and analyzed them to explore topics,

genres, and sentiment of those books. We applied text mining methods for data

analysis, such as term frequency and network analysis, LDA topic modeling, and

sentiment analysis.

Literature Review

Theoretical Framework

Picture books

serve as unique multimodal sources of information in which verbal and visual

elements combine and interact to convey meaning (Martens et al., 2012). The

tension between visual and verbal modes—the tendency to slowly gaze upon images

and layout versus the forward momentum of reading text—make the picture book

reading experience distinct and synergistic (Sipe, 1998). Serafini (2012) has

posited four roles essential for picture book reading: 1) the navigator role

entails proficiently employing conventions of print and cognitive strategies

and skills to move through the written text while simultaneously making sense

of the visual design and images; 2) the interpreter role consists of meaning

making; 3) in acting as a designer, the reader determines the path through

which a text is experienced by determining the order of attention to and

importance of textual and visual elements; and 4) in enacting the interrogator

role, the reader serves as a critical analyst acknowledging that messages and

interpretations are socially constructed and politically, socially, and

culturally powerful. Using Eisenberg and Small’s (1993) framework for

information-based education, Campana (2018) demonstrated that information

resources, information process, and individuals interact within the storytime

context to provide learning opportunities for all involved. As a primary

information resource within storytime programs, picture books are an important

element of the storytime learning environment, and the storytime librarians’

processes facilitate children’s picture book reading and meaning making.

General Content of Children’s Books

Nearly half of

all picture books published in English in the United States feature animals as

leading characters (Horning, 2016). Preschool-aged children have shown an

aesthetic preference for artwork, such as picture book covers, that feature

animals (Danko-McGhee & Slutsky, 2011). Markowsky (1975) pointed to four reasons why children’s

book authors and illustrators might choose animal characters: a) void of the

accoutrements associated with specific groups of people, animal characters are

relatable to children of all stripes and circumstances; b) animal characters

produce an element of whimsy, enabling escape, inspiration, and imagination; c)

animal characters serve as a form of shorthand or symbolic representation; and

d) animal characters with exaggerated features and characteristics lend an

element of humor.

Book Choice in Preschool Education

Several studies

have examined characteristics of books read aloud in preschool classrooms and

centers. Mesmer (2018) interviewed the staff of 31 preschool centers in the

southwestern United States who expressed that the characteristics they

considered most frequently were illustrations, rhyme, length, simple content,

and a topic relevant to children. When examining the genres of such books,

researchers have noted a lack of informational books (Pentimonti

et al., 2011; Thoren, 2016). This is concerning

because sharing informational books provides many educational benefits to

children, such as content knowledge and preparation for successfully reading

this genre in school (Lennox, 2013; Neuman et al., 2016), and because children

are highly interested in informational books (Baldwin & Morrow, 2019; Price

et al., 2012). In addition, studies of preschool classrooms revealed a lack of

concept books, or books that focused on foundational academic topics such as

counting and the alphabet (Gou et al., 2013; Pentimonti

et al., 2011).

Book Choice in Public Library Storytimes

Diamant-Cohen

and Hetrick (2014) contended that “the main goal of preschool storytime is to

help children develop a positive connection with books and illustrations, which

will later translate into a positive attitude toward books in general” (p. 4).

To accomplish this goal, librarians typically incorporate three to four books

in each storytime program (Diamant-Cohen & Hetrick, 2014; Goulding et al.,

2017; Kociubuk & Campana, 2019). Naturally, the

topics and sentiment of books shared in public library storytime programs will

affect the extent to which children develop a positive connection; thus,

librarians’ book choices are important.

Despite the

importance of book choice, only a few studies have examined the characteristics

of books chosen for storytime programs. One study examined the books shared in

69 baby, toddler, preschool, and family storytimes in public libraries in the

state of Washington during 2013 (Kociubuk &

Campana, 2019). The book characteristics collected were genre (fiction or

nonfiction) and publication date; thus, this study does not provide insight

into the topic or sentiment of storytime books. In contrast, two surveys of

professionals who choose storytime books revealed that they did take into account the topic and other aspects of a book’s

content (Carroll, 2015; Fullerton et al., 2018). Carroll (2015) identified

seven influential factors in book selection: length and complexity;

illustrations; subjects, concepts, and themes; use of language such as rhyme

and repetition; how easily the book could be used to invite audience

participation; elements such as suspense or humor that could emotionally engage

the children; and personal preference. Similarly, respondents to Fullerton et

al.’s (2018) survey chose language use and illustrator’s craft as top

considerations when selecting books.

Objectives of Public Library Storytimes

One of the

important program objectives of storytimes lies in learning and education

(Campana, 2018; Fehrenbach et al., 1998; Peterson,

2012). Storytime providers have long emphasized early literacy development of

young children when designing programs (Albright et al, 2009), but scholars

have recently noted the broader role libraries play in supporting school

readiness (Campana, 2018). Storytime serves as a valuable opportunity for

children to build knowledge structures of colors, numbers, singing, alphabet,

and more (Cahill et al., 2018). According to Celano

and Neuman (2001), “by reading books, telling stories, and reciting rhymes,

librarians offer children a ‘leg up’ in developing emergent reading skills” (p.

39).

While parents

and caregivers certainly value storytimes for the learning opportunities they

afford, many view these programs as family entertainment venues (Khoir et al., 2017) and worthy experiences simply because of

the joy they bring to children (Cahill et al., 2020). Most storytime programs

offer opportunities for children and adults to interact, play, and sing (Celano & Neuman, 2001). Stories told in rhymes and

picture book versions of songs, in addition to encouraging playful interaction,

may aid children in developing early literacy skills such as phonological

awareness (Giles & Fresne, 2015).

Additionally,

storytimes serve as opportunities to stimulate and extend children’s feelings

and emotional experiences because reading children’s literature can be a source

of emotional learning for children (Short, 2018; Thoren,

2016) and shared book reading has been found to be a viable activity to help

children build socio-emotional competence (Schapira

& Aram, 2019). Further, a majority of literacy educators, including

librarians, regard social emotional learning as a responsibility of literacy

educators but one for which they need further support (International Literacy

Association, 2020).

The Aim and Research Questions of the

Study

Storytime programs for young children are offered in

nearly all public libraries. However, few researchers have investigated the

topics and content of the books that librarians use in such programs. It is

important to have a better understanding of the content of the books to produce

best practices and suggestions for book selection in storytimes for young

children. Our overarching aim through this study was to explore topics and

genres of the books that are read in storytimes for young children in public

libraries. In addition, we aimed to examine the nature of sentiment represented

in books widely used in storytimes for young children. The methodological

contribution of this study is that it employed computational text analysis

methods to investigate the content of a large sample size of books recommended

for library storytime programs. The following two research questions guide the

investigation of this study:

RQ 1. What are the topics and genres of books

recommended for public library storytime programs designed for preschool

children?

RQ 2. What is the nature of sentiment represented in

books recommended for public library storytime programs designed for preschool

children?

Table 1

Online Resources for Storytime Chosen for This Study

|

Resource |

Number

of Total Themes |

Number

of Themes in Stratified Random Sample |

|

Esther

Storytimes |

74 |

15 |

|

Jbrary |

19 |

4 |

|

MCLS

kids |

158 |

32 |

|

Silly

Librarian Preschool |

100 |

20 |

|

Storytime

Katie |

195 |

39 |

|

Storytime

Secrets |

70 |

14 |

|

Total |

616 |

124 |

Methods

To identify informal sources that storytime providers

were likely to encounter and use, we conducted a simple Internet search for

“storytime resources for librarians.” We then selected the first six sources

that recommended books for storytime use based on theme: Esther Storytimes, Jbrary, MCLS Kids, Silly Librarian,

Storytime Katie, and Storytime Secrets. We next created a

list of all preschool storytime themes shared on each site, which totaled 616

in all (Table 1). Because each theme contained multiple book recommendations,

including the entire population would be laborious and unfeasible from a data

preparation standpoint; thus, we randomly selected 20% of the themes, resulting

in 124 themes in the sample. For each theme, we recorded the name and author of

each book recommended as supporting the theme and appropriate for storytime.

In this study, we analyzed largely two types of

textual information collected about each book from the WorldCat database:

“titles and abstracts” and “subject terms.” We excluded any books that did not

have an abstract available from WorldCat. After removing them from the book

list, 429 books were used for analysis. Two sets of text corpus data were made

for text mining: (1) titles and abstracts and (2) subject terms.

Multiple text mining techniques were employed to

explore the content of storytime books. First, a term frequency analysis was

conducted to identify the most frequent terms that occurred in each corpus. The

collected text underwent a pre-processing process, including tokenization, stopword elimination, and stemming. In addition, bi-grams

were further investigated to identify key concepts or popular genres in

storytime books. Second, we analyzed the relationships among the terms based on

term co-occurrence analysis. A term co-occurrence map was created to identify

key topics and genres in storytime books. Third, Latent Dirichlet Allocation

(LDA) topic modeling was applied to uncover prevailing topics underlying the

books commonly recommended for storytimes. LDA topic modeling is an

unsupervised machine learning method to discover hidden themes or topics from

unstructured text (Blei, 2012). We extracted 20

topics from the corpus of titles and abstracts. Fourth, we explored the nature

of emotion reflected in storytime books by analyzing sentiment terms. The

sentiment lexicon constructed by Liu (2015) was adopted to investigate

emotional aspects of the text from storytime books. The bing

lexicon classifies selected words into the binary categories, i.e., positive

and negative sentiment categories (https://www.cs.uic.edu/~liub/FBS/sentiment-analysis.html).

Textual analysis was conducted using various R

software packages. R is a software tool that can be used for statistical

analysis and data science, and it includes a multitude of packages for natural

language processing and text mining. For term frequency analysis, two packages

were mainly used: R tm and R tidy. For the LDA topic model, the R topic models

package was employed.

Results

RQ 1. What are the topics and genres of books recommended for public library storytime programs designed for preschool children?

First, we

calculated the most frequent terms from the corpus of titles and abstracts. It

exhibited 2,289 unique terms and 7,718 tokens after removing stopwords. In textual analysis, a unique word (also called

type) refers to a distinct term in a corpus while a token indicates an

occurrence of a unique type (Jackson & Moulinier,

2007). We investigated the top 96 stemmed terms that appeared more than 15

times (Appendix A). The two most frequent terms are “book” (1st, 1.35%) and “anim” (2nd, 1.17%). Abstracts usually summarize the books,

so it is not a surprise that the term “book” occurred most frequently from the

corpus. Interestingly, “anim,” which indicated the

term of “animal(s),” was observed second most frequently. In addition, there

were other animal-related terms observed among top ranked terms; for instance,

“bear” (3rd), “cat” (15th), and “dog” (21st), among several others. The results

also included several terms associated with early learning, such as “color”

(8th), “rhyme” (12th), “alphabet” (26th), “read” (43rd), and “count” (82nd).

Another distinct group of frequent terms can be classified as book audiences or

characters, such as “young” (7th), “babi” (9th),

“children” (10th), “boy” (12th), and “reader” (23rd). In addition, several

terms were related to actions or movements, such as “play” (3rd), “find” (3rd),

and “danc” (37th). We also observed terms depicting

emotion, such as “love” (3rd), “fun” (43rd), and “enjoy” (82nd).

We next turned

attention to the “subject terms” corpus and tallied frequencies of the terms

observed in it. The corpus consisted of 538 unique terms and 3,642 tokens.

Subject terms were much shorter than the combinations of titles and summaries.

Also, this corpus mostly consisted of nouns with only few adjectives or verbs

observed. The top 82 most frequent terms that appeared more than five times are

listed in Appendix B. The analysis showed that subject terms are likely to

provide genre information or more condensed topic terms. The two top-ranked

terms indicated genres of books: “fiction” (1st, 25.95%) and “juvenil” (2nd, 13.40%). WorldCat organizes books by genre

using subject headings. For example, A

Fairy-Tale Fall by Apple Jordan has three subject terms: “Autumn --

Juvenile fiction,” “Princesses -- Juvenile fiction,” and “Halloween -- Juvenile

fiction,” and represents a typical format of WorldCat subject terms, which is a

combination of a topical term and a genre. Thus, genre related terms were a

frequent observation from the corpus. Other genre classification terms that

ranked highly included “stori” (3rd), “rhyme” (6th),

“literatur” (7th), “pictori”

(10th), “picture” (15th), “movabl” (17th), and

several others. This finding implied that most storytime books could be

categorized as juvenile fiction, stories in rhyme, pictorial works, picture

books, or movable books. We can also infer that storytime books involved other

genres, such as “folklore” (24th), “poetri” (26th),

and “nonfict” (55th).

In addition,

subject terms depicted prevalent topics in storytime books. Interestingly,

similar to the results from the titles and abstracts, the term “anim” is ranked highly at 5th, revealing the popularity of

animal related topics in storytimes. Animal related terms included “dog”

(19th), “bear” (20th), “cat” (24th), “rabbit” (46th), and several others.

Several of the terms implied topics related to knowledge and skills important

for young children; for example “count” (20th), “song”

(28th), “alphabet” (34th), “sound” (46th), “scienc”

(46th), “read” (68th), and “languag” (83rd).

Storytime books also reflected social and behavioural

topics, such as “friendship” (46th), “behavior” (61st), and “social” (68th).

Other notable topics or concepts that children can learn included: family

(e.g., “famili” (32nd), “mother” (34th), “parent”

(46th), “son” (61st), and “father” (55st)), nature (e.g., “natur”

(32nd), “snow” (46th), “moon” (61st), and “tree” (83rd)), settings (e.g.,

“farm” (39th), “garden” (46th), and “zoo” (83rd)), Halloween (e.g., “Halloween”

(34th) and “pumpkin” (68th)), and other objects/characters (e.g., “monster”

(55rd), “pirat” (61st), and “dinosaur” (68th)).

We further

analyzed bi-gram terms, which indicated two adjacent tokens, from the titles

and abstracts corpus. In total, 9,018 unique bi-grams were observed after

removing stopwords. Appendix C lists the top 44

bi-gram terms that were counted four times or more. The top two bi-grams are

“picture book” and “rhyming text.” Also, among the ranked bi-grams, there were

bi-grams that indicated the types of books, including “board book,” “simple

text,” and “illustrations rhyming.” This finding highlighted that the nature of

storytime books related to pictures, rhymes, and simple text to be shared with

young children. The bi-gram analysis result also showed popular topics and

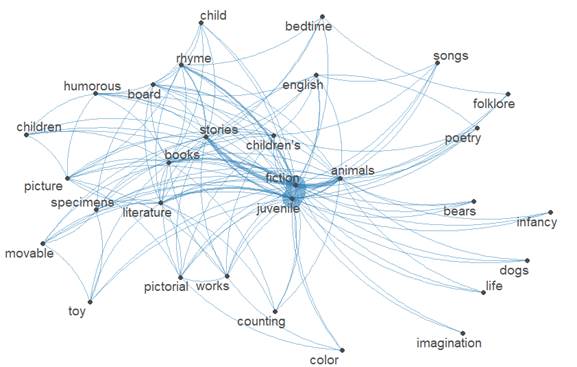

characters in storytime books. As shown in Figure 1, a term co-occurrence

network revealed relationships among key terms in storytime books. The term

“book” showed close associations with “picture,” “children,” and “animal,”

which reveals popular types of books in storytimes. Another notable linking

group is made of “text,” “illustrations,” and “rhyming.”

The same bi-gram

analysis was conducted for the subject terms (Appendix D). In total, 3,250

bi-grams (1,312 unique bi-gram types) were observed. The most frequent bi-grams

indicated the genres or types of storytime books; for example

“juvenile fiction,” “juvenile literature,” “fiction stories,” “board books,”

“pictorial works,” and so on. The visualization of term co-occurrence analysis

highlighted the genres of storytime books as it placed “juvenile” and “fiction”

among other genre terms in the center of the network diagram (Figure 2).

To explore

popular topics in storytime books, we derived 20 topics from the titles and

abstracts corpus using the LDA topic model (Table 2). Not all topics exhibit

distinct and coherent thematic terms, but we found that these topics can be

classified largely into several categories. There are several learning components

observed from the extracted topics: for example, T7 (e.g., alphabet, letter)

and T4 (e.g., color, crayon, count). Animals and creatures were another

prominent topic in storytimes, such as T6 (e.g., cat,

dog), T2 (e.g., mouse, spider, pigeon), and T11 (e.g., bear, elephant). The LDA

topic model also detected topic terms relevant to book types, such as T9 (e.g.,

book, illustration), T14 (e.g., rhyme, illustration, and interactive) and T20

(e.g., illustration, rhyme). The components of activities, actions, and

movements were also reflected in storytime books: for

example, T5 (e.g., dance, swim, discover) and T4 (e.g., play). Moreover, topic

terms obtained from the LDA algorithm represented other aspects of topics

covered in storytime books, ranging from audiences

(e.g., children, young reader), friends and families (e.g., friend, family,

mother), nature (e.g., tree, sky, flower), settings (e.g., farm, garden), and

emotions (e.g., fun, love, happy).

Figure 1

A network of

term co-occurrence relationships: titles and abstracts.

Figure 2

A network of

term co-occurrence relationships: subject terms.

Table 2

LDA Topic Model

(20 Topics)

|

T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

T4 |

T5 |

T6 |

T7 |

T8 |

T9 |

T10 |

|

night fun stop home busi visit pig differ follow pictur |

mous spider includ pigeon back web mommi cooki long varieti |

hat magic text rabbit classic pop best name treasur chicken |

play color crayon children creat heart zoo bestsel count time |

danc pumpkin halloween swim discov five favorit board pirat grade |

cat love dog shoe imagin pete around white kitti sing |

alphabet letter featur differ time pictur world full pea everi |

grow follow mani plant turn tree eat forest celebr librari |

book illustr life old artist time cut journey color easi |

egg girl back salli bug butterfli ice big chick bring |

|

T11 |

T12 |

T13 |

T14 |

T15 |

T16 |

T17 |

T18 |

T19 |

T20 |

|

bear big boy brown bus eleph tree celebr around cake |

find boy tri song pictur school describ best everyth join |

farm bunni mother text dinosaur tale bed amaz world readi |

young reader rhyme garden illustr moon children interact reveal edit |

stori give introduc train blanket surpris children includ sit answer |

perfect famili crocodil keep three full live water know show |

anim tail page cloth enjoy everyon wear parent louis aloud |

book babi love penguin toe red along delight flap page |

friend read simpl snow tri sheep monster kiss text hous |

appl ten illustr tree rhyme leav gingerbread pie simpl trick |

RQ 2. What is the nature of sentiment represented in books recommended for public library storytime programs designed for preschool children?

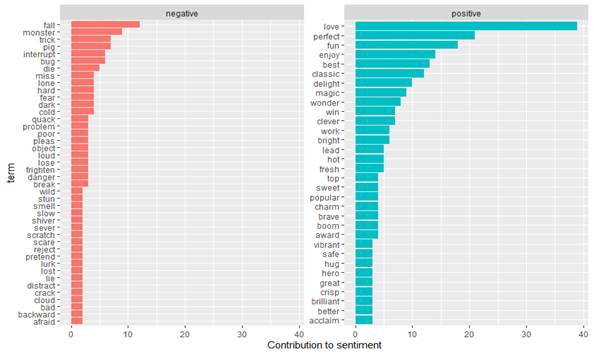

Sentiment analysis was conducted to explore the

emotional aspects of storytime language. We identified the top 25 positive and

negative terms respectively (Figure 3). Overall, there were more positive terms

than negative terms observed from the titles and abstracts corpus. Frequently

observed positive terms include “like,” “love,” “perfect,” “fun,” “classic,”

“favorite,” and others. These positive terms described storytime books as

likable, easy, fun, enjoyable, playful, happy, and other upbeat descriptions.

On the contrary, there were fewer negative terms observed. The top ranked

negative term turned out to be “fall.” According to our further observation,

however, there were more cases when the term “fall” was used to indicate the

season, rather than an act of falling or moving down: for example, “a little

girl spends a glorious fall day picking apples and searching for the perfect

pumpkin in this edition of a timeless favorite” in the book Apples and Pumpkins

by Anne Rockwell. Other negative terms did not necessarily have any negative

nuance in the context of children's stories. For instance, pigs and bugs are

likely to be featured as friendly characters rather than unpleasant objects in

storytime books. Despite the nuance based on context, other terms appeared with

obvious negative connotations, such as “die,” “tired,” “trouble,” “lonely,”

“skeptical,” “fear,” and others.

Figure 3

Positive and

negative terms in storytime books.

Discussion

By analyzing the most frequent terms, we explored

different aspects of storytime books, such as popular topics, audiences, and

styles or techniques for sharing the books. Not surprisingly, animals were a

major topic in these recommended books just as they are in picture books in

general (Horning, 2016). In our results, various types of animals were ranked

highly, such as bear, cat, dog, mouse, and rabbit. Because preschool-age

children have shown a preference for artwork that features animals (Danko-McGhee & Slutsky, 2011), our results indicated

that sharing these recommended books would appeal to children’s interests.

The frequent terms also pointed to opportunities to

integrate school readiness and other elements of early learning into storytime

programs. Several different concepts related to children’s learning were

observed, such as color, rhymes, alphabet, read, song, and count. The use of

concept books may be especially important in public library storytimes to give

children additional support in these content areas because studies have found

that preschool classrooms and centers may offer only small numbers of concept

books (Guo et al., 2013; Pentimonti et al., 2011).

Additionally, the findings coincided with the storytime providers’ preference

for concept books that may engage and empower children with familiar,

repetitive content (Carroll, 2015). The frequency of terms related to early

learning concepts indicated that providers can use these recommended books to

achieve the school readiness related objectives of storytimes.

The term frequency analysis also pointed to

opportunities for librarians to structure storytimes as emotionally positive

and fun. Frequent terms included “play,” “love,” “fun,” “enjoy,” and “dance.”

Based on attendees’ expectations that storytimes are a place for entertainment

(Khoir et al., 2017) and joyful experiences (Cahill

et al., 2020), sharing these recommended books can be part of meeting

attendees’ expectations and accomplishing storytime objectives.

The analysis of subject terms illuminated popular

genres of storytime books as they tended to include controlled heading terms of

book genres/categories. The top 10 terms identified the most common genres of

books shared in storytimes: fiction, juvenile, story books, rhymes, children's

literature, board books, and pictorial works. We found that storytime books

also included poetry, folklore, and nonfiction, although to a much smaller

extent. These findings were similar to those of Kociubuk

and Campana (2019), who found that less than 10% of stories shared in

storytimes were in the narrative informational or non-narrative informational

genres.

The term-level analysis revealed both visual and sound

modes of story delivery in storytimes. Terms related to visual mode, such as

pictures and illustrations, were highly ranked in both the corpuses. Also,

storytime books actively involved sound modes, in particular, rhymes and songs.

That is, storytime books are not simply text of stories, they promote

interactivity through multiple modes by utilizing both visual and sound sensory

channels to deliver stories to children. The importance of visual elements as a

rationale for choosing books for read-alouds is

reflected in research with children, storytime providers, children’s literature

experts, and early childhood education teachers (Carroll, 2015; Danko-McGhee & Slutsky, 2011; Fullerton et al., 2018;

Mesmer, 2018).

Movements and actions are another mode to facilitate

interactions and are often integrated into storytimes; however, not many

action/movement terms were observed among the top terms. This may be because

storytime providers plan to get the audience moving before or after reading

books aloud through activities such as songs, rhymes, or fingerplays (Giles

& Fresne, 2015; Kociubuk

& Campana, 2019).

We also explored emotional aspects of storytime books

based on sentiment analysis. Overall, the sentiment nature of the storytime

context is very positive, showing more positive vocabulary proportionately in

this study. That is, the fundamental atmosphere of storytimes would be very

positive and enjoyable. In addition, we observed that storytime books included

various words representing emotion. They can be sources for children to learn

and understand a diverse spectrum of emotion and sentiment, thus giving

providers the opportunity to contribute to children’s social-emotional

learning, another objective of storytime programs.

This study was not without limitations. First, the

analysis was done with the bibliographic records from the WorldCat database.

The dataset consisted of titles, abstracts, and subject terms of the selected

books, but it did not include full-text. Second, the sample of 429 books might

not represent the entire book selection in storytime practices. The books

included are recommended widely across the storytime community, but there is no

information on which books are actually adopted and read in the field. Third,

several of the terms were not interpreted correctly in the sentiment analysis

as the computational tool did not catch the meaning or nuance currently in the

context. For example, the word “fall” was categorized into the negative terms

even though it indicated the season. These limitations indicated a need for

further research, which can investigate full-text content of an enlarged sample

of storytime books. Future research can also develop a sophisticated method to

better analyze topical terms and sentiment based on text mining. Additionally,

the complexity of language can be investigated to assess the levels of

vocabulary exposed to children via storytimes.

Conclusion

In this study, we employed a text mining approach to

explore topics of storytime books. We identified 429 books recommended for use

in public library storytime sessions designed for preschool age children, and

we collected two corpuses of text from the WorldCat database based on these

books: a) titles and abstracts, and b) subject terms. To investigate the nature

of theme and sentiment in storytime books, we applied multiple text mining

techniques for the collected text, such as term frequency analysis, bi-grams

analysis, term co-occurrences network analysis, LDA topic modeling, and

sentiment analysis. The findings revealed popular topics and genres as well as

emotional terms that would likely be addressed in storytimes drawing from these

sources.

So what? Why does it matter what books librarians may

choose to share with children and caregivers during storytime? According to

Sipe (2008), “literature … allows us to perceive our lives, the lives of

others, and our society in new ways, expanding our view of what is possible,

serving as a catalyst to ignite our capacity to imagine a more just and

equitable world. To understand stories and how they work is thus to possess a

cognitive tool that not only allows children to become comprehensively

literate, but also to achieve their full human potential” (p. 247). Our

findings suggested that the books recommended for storytime programs hold the

promise of preparing children for school and for life.

Author Contributions

Soohyung Joo:

Conceptualization, Data collection, Data analysis, Investigation, Writing –

original draft, Writing – revision and editing Erin Ingram: Conceptualization, Data collection, Literature review,

Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – revision and editing Maria Cahill: Conceptualization, Data

collection, Literature review, Investigation, Discussion, Writing – original

draft, Writing – revision and editing.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Institute of Museum and

Library Services (Federal Award Identification Number: LG-96-17-0199-17). We

are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.

References

Albright, M., Delecki, K.,

& Hinkle S. (2009). The evolution of early literacy. Children & Libraries, 7(1), 13–18.

Baldwin, C. G., & Morrow, L. M. (2019).

Interactive shared book reading with a narrative and an informational book: The

effect of genre on parent-child reading. Preschool

& Primary Education, 7(2), 81–101. https://doi.org/10.12681/ppej.20909

Blei, D. M. (2012).

Probabilistic topic models. Communications

of the ACM, 55(4), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1145/2133806.2133826

Cahill, M., Joo, S., &

Campana, K. (2018). Analysis of language use in public library storytimes. Journal of Librarianship & Information

Science, 52(2), 476–484. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000618818886

Cahill, M., Joo, S., Howard,

M., & Walker, S. (2020). We’ve been offering it for years, but why do they

come? The reasons why adults bring young children to public library storytimes.

Libri, 70(4), 335–344. https://doi.org/10.1515/libri-2020-0047

Campana, K. (2018). The multimodal power of storytime: Exploring an information environment

for young children (Publication No. 10825573) [Doctoral dissertation,

University of Washington]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Carroll, V. (2015). Preschool storytime in Auckland’s public libraries: A qualitative study

of book selection practices [Master’s thesis, Victoria University of

Wellington]. Victoria University of Wellington Research Archive. https://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/xmlui/handle/10063/4690

Celano, D., &

Neuman, S. B. (2001). The role of public

libraries in children’s literacy development: An evaluation report. Pennsylvania

Library Association.

Danko-McGhee, K.,

& Slutsky, R. (2011). Judging a book by its cover: Preschool children’s

aesthetic preferences for picture books. International

Journal of Education through Art, 7(2), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1386/eta.7.2.171_1

Diamant-Cohen, B., & Hetrick, M. A. (2014). Transforming preschool storytime: A modern vision and a year of

programs. American Library Association Neal-Schuman.

Eisenberg, M. B., & Small, R. V. (1993).

Information-based education: An investigation of the nature and role of

information attributes in education. Information

Processing and Management, 29(2), 263–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4573(93)90010-B

Fehrenbach, L. A., Hurford, D. P., Fehrenbach, C.

R., & Brannock, R. G. (1998). Developing the

emergent literacy of preschool children through a library outreach program. Journal of Youth Services, 12(1), 40-45.

Fullerton, S. K., Schafer, G. J., Hubbard, K.,

McClure, E. L., Salley, L., & Ross, R. (2018). Considering quality and

diversity: An analysis of read-aloud recommendations and rationales from

children’s literature experts. New Review

of Children's Literature and Librarianship, 24(1), 76–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614541.2018.1433473

Giles, R. M., & Fresne, J. (2015). Musical

stories infusing your read-alouds with music,

movement, and sound. Public Libraries,

54(5), 31–34. http://publiclibrariesonline.org/2015/11/musical-stories-infusing-your-read-alouds-with-music-movement-and-sound/

Ghoting, S., & Martin-Diaz,

P. (2006). Early literacy storytimes @

your library: Partnering with caregivers for success. American Library Association.

Goulding, A., Dickie, J., & Shuker, M. J. (2017).

Observing preschool storytime practices in Aotearoa New Zealand's urban public

libraries. Library & Information

Science Research, 39(3), 199–212.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2017.07.005

Guo, Y., Sawyer, B. E., Justice, L. M., & Kaderavek, J. N. (2013). Quality of the literacy

environment in inclusive early childhood special education classrooms. Journal of Early Intervention, 35(1), 40–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815113500343

Horning, K. T. (2016, July 28). Drilling down on

diversity in picture books. CCBlogC. https://ccblogc.blogspot.com/2016/07/drilling-down-on-diversity-in-picture.html

International Literacy Association. (2020). What’s hot in literacy report. https://www.literacyworldwide.org/docs/default-source/resource-documents/whatshotreport_2020_final.pdf

Jackson, P., & Moulinier,

I. (2007). Natural language processing

for online applications: Text retrieval, extraction and categorization.

John Benjamins.

Khoir, S., Du, J. T.,

Davison, R. M., & Koronios, A. (2017).

Contributing to social capital: An investigation of Asian immigrants’ use of

public library services. Library &

Information Science Research, 39(1), 34-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2017.01.005

Kociubuk, K. J., &

Campana, K. (2019). Sharing stories: An exploration of genres in storytimes. Journal of Librarianship and Information

Science, 52(3), 905–915. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000619882751

Lennox, S. (2013). Interactive read-alouds – An avenue for enhancing children's language for

thinking and understanding: A review of recent research. Early Childhood Education Journal, 41(5), 381–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-013-0578-5

Liu, B. (2015). Sentiment

analysis: Mining opinions, sentiments, and emotions. Cambridge University

Press.

Markowsky, J. K. (1975).

Why anthropomorphism in children’s literature? Elementary English, 52(4), 460-462, 466.

Martens, P., Martens, R., Doyle, M. H., Loomis, J.,

& Aghalarov, S. (2012). Learning from picturebooks: Reading and writing multimodally in first

grade. The Reading Teacher, 66(4),

285-294. https://doi.org/10.1002/TRTR.01099

Mesmer, H. A. (2018). Books, read-alouds,

and voluntary book interactions: What do we know about centers serving

three-year-olds? Literacy

Research and Instruction, 57(2),

158–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388071.2017.1347220

Miller, C., Zickuhr, K., Rainie, H., & Purcell,

K. (2013). Parents, children, libraries,

and reading. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2013/05/01/parents-children-libraries-and-reading-3/

Mills, J. E., Campana, K., Carlyle, A., Kotrla, B., Dresang, E. T.,

Urban, I. B., Capps, J. L., Metoyer, C., Feldman, E. N., Brouwer, M, &

Burnett, K. (2018). Early literacy in library storytimes, part 2: A

quasi-experimental study and intervention with children’s storytime providers. Library Quarterly: Information, Community,

Policy, 88(2), 160–176. https://doi.org/10.1086/696581

Neuman, S. B., Kaefer, T., &, Pinkham, A. M.

(2016). Improving low-income preschoolers’ word and word knowledge: The effects

of content-rich instruction. The

Elementary School Journal, 116(4),

652–674. https://doi.org/10.1086/686463

Pentimoti, J. M., Zucker,

T. A., & Justice, L. M. (2011). What are preschool teachers reading in

their classrooms? Reading Psychology, 32(3),

197–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711003604484

Peterson, S. S. (2012). Preschool early literacy

programs in Ontario public libraries. Partnership:

The Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 7(2),

1–21. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v7i2.1961

Price, L. H., Bradley, B. A., & Smith, J. M.

(2012). A comparison of preschool teachers’ talk

during storybook and information book read-alouds. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27(3), 426–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.02.003

Schapira, R., &

Aram, D. (2019). Shared book reading at home and preschoolers’ socio-emotional

competence. Early Education and

Development, 31(6), 819–837. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2019.1692624

Serafini, F. (2012). Expanding the four resources

model: Reading visual and multi-modal texts. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 7(2), 150–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554480X.2012.656347

Short, K. G. (2018). What’s trending in children’s

literature and why it matters. Language

Arts, 95(5), 287–298. https://old.coe.arizona.edu/sites/default/files/pages/files/whats-trending-childrens-literature.pdf

Sipe, L. R. (1998). How picture books work: A

semiotically framed theory of text-picture relationships. Children's Literature in Education, 29(2), 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022459009182

Sipe, L. (2008). Storytime:

Young children’s literary understanding in the classroom. Teachers College

Press.

Thoren, J. E. (2016). Exploring preschool teachers’ perceptions regarding

the barriers to selecting literature genres and utilizing extension activities:

A qualitative multiple case study (Publication No. 10240705) [Doctoral

dissertation, Northcentral University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses

Global.

Appendix A

Most

Frequent Terms from the Titles and Abstracts Corpus

|

Rank |

Term |

Freq. |

Percent |

Rank |

Term |

Freq. |

Percent |

|

1 |

book |

104 |

1.35% |

43 |

full |

19 |

0.25% |

|

2 |

anim |

90 |

1.17% |

50 |

back |

18 |

0.23% |

|

3 |

love |

48 |

0.62% |

50 |

bed |

18 |

0.23% |

|

3 |

bear |

48 |

0.62% |

50 |

everyon |

18 |

0.23% |

|

3 |

find |

48 |

0.62% |

50 |

magic |

18 |

0.23% |

|

3 |

play |

48 |

0.62% |

50 |

garden |

18 |

0.23% |

|

7 |

young |

45 |

0.58% |

50 |

old |

18 |

0.23% |

|

8 |

color |

42 |

0.54% |

56 |

follow |

17 |

0.22% |

|

9 |

babi |

39 |

0.51% |

56 |

celebr |

17 |

0.22% |

|

10 |

children |

38 |

0.49% |

56 |

toe |

17 |

0.22% |

|

11 |

illustr |

37 |

0.48% |

56 |

just |

17 |

0.22% |

|

12 |

boy |

36 |

0.47% |

56 |

farm |

17 |

0.22% |

|

12 |

rhyme |

36 |

0.47% |

56 |

egg |

17 |

0.22% |

|

14 |

text |

35 |

0.45% |

56 |

board |

17 |

0.22% |

|

15 |

tri |

33 |

0.43% |

56 |

monster |

17 |

0.22% |

|

15 |

cat |

33 |

0.43% |

56 |

home |

17 |

0.22% |

|

17 |

stori |

32 |

0.41% |

65 |

surpris |

16 |

0.21% |

|

18 |

tree |

31 |

0.40% |

65 |

girl |

16 |

0.21% |

|

19 |

friend |

30 |

0.39% |

65 |

busi |

16 |

0.21% |

|

19 |

pictur |

30 |

0.39% |

65 |

learn |

16 |

0.21% |

|

21 |

dog |

29 |

0.38% |

65 |

shoe |

16 |

0.21% |

|

21 |

time |

29 |

0.38% |

65 |

featur |

16 |

0.21% |

|

23 |

reader |

28 |

0.36% |

71 |

child |

15 |

0.19% |

|

23 |

mani |

28 |

0.36% |

71 |

crayon |

15 |

0.19% |

|

23 |

big |

28 |

0.36% |

71 |

goe |

15 |

0.19% |

|

26 |

alphabet |

25 |

0.32% |

71 |

keep |

15 |

0.19% |

|

26 |

page |

25 |

0.32% |

71 |

kiss |

15 |

0.19% |

|

28 |

simpl |

24 |

0.31% |

71 |

beauti |

15 |

0.19% |

|

28 |

night |

24 |

0.31% |

71 |

pumpkin |

15 |

0.19% |

|

28 |

world |

24 |

0.31% |

71 |

stop |

15 |

0.19% |

|

28 |

hat |

24 |

0.31% |

71 |

give |

15 |

0.19% |

|

32 |

grow |

23 |

0.30% |

71 |

school |

15 |

0.19% |

|

32 |

mother |

23 |

0.30% |

71 |

snow |

15 |

0.19% |

|

32 |

includ |

23 |

0.30% |

82 |

crocodil |

14 |

0.18% |

|

35 |

ten |

22 |

0.29% |

82 |

count |

14 |

0.18% |

|

35 |

appl |

22 |

0.29% |

82 |

best |

14 |

0.18% |

|

37 |

perfect |

21 |

0.27% |

82 |

around |

14 |

0.18% |

|

37 |

danc |

21 |

0.27% |

82 |

creat |

14 |

0.18% |

|

37 |

red |

21 |

0.27% |

82 |

enjoy |

14 |

0.18% |

|

40 |

penguin |

20 |

0.26% |

82 |

share |

14 |

0.18% |

|

40 |

know |

20 |

0.26% |

82 |

everyth |

14 |

0.18% |

|

40 |

famili |

20 |

0.26% |

82 |

introduc |

14 |

0.18% |

|

43 |

fun |

19 |

0.25% |

82 |

spider |

14 |

0.18% |

|

43 |

water |

19 |

0.25% |

82 |

imagin |

14 |

0.18% |

|

43 |

read |

19 |

0.25% |

82 |

heart |

14 |

0.18% |

|

43 |

discov |

19 |

0.25% |

82 |

bath |

14 |

0.18% |

|

43 |

differ |

19 |

0.25% |

82 |

song |

14 |

0.18% |

|

43 |

mous |

19 |

0.25% |

82 |

duck |

14 |

0.18% |

Appendix B

Most Frequent Terms from the Subject Terms

|

Rank |

Term |

Freq. |

Percent |

Rank |

Term |

Freq. |

Percent |

|

1 |

fiction |

945 |

25.95% |

39 |

appl |

10 |

0.27% |

|

2 |

juvenil |

488 |

13.40% |

39 |

domest |

10 |

0.27% |

|

3 |

stori |

126 |

3.46% |

39 |

farm |

10 |

0.27% |

|

4 |

book |

110 |

3.02% |

39 |

play |

10 |

0.27% |

|

5 |

anim |

99 |

2.72% |

46 |

scienc |

9 |

0.25% |

|

6 |

rhyme |

81 |

2.22% |

46 |

rabbit |

9 |

0.25% |

|

7 |

literatur |

60 |

1.65% |

46 |

american |

9 |

0.25% |

|

8 |

children |

55 |

1.51% |

46 |

parent |

9 |

0.25% |

|

9 |

board |

50 |

1.37% |

46 |

garden |

9 |

0.25% |

|

10 |

pictori |

42 |

1.15% |

46 |

sound |

9 |

0.25% |

|

11 |

work |

41 |

1.13% |

46 |

friendship |

9 |

0.25% |

|

12 |

humor |

27 |

0.74% |

46 |

text |

9 |

0.25% |

|

13 |

toy |

23 |

0.63% |

46 |

snow |

9 |

0.25% |

|

13 |

specimen |

23 |

0.63% |

55 |

penguin |

8 |

0.22% |

|

15 |

pictur |

22 |

0.60% |

55 |

fictiti |

8 |

0.22% |

|

16 |

color |

21 |

0.58% |

55 |

monster |

8 |

0.22% |

|

17 |

english |

19 |

0.52% |

55 |

nonfict |

8 |

0.22% |

|

17 |

movabl |

19 |

0.52% |

55 |

duck |

8 |

0.22% |

|

19 |

dog |

18 |

0.49% |

55 |

father |

8 |

0.22% |

|

20 |

count |

17 |

0.47% |

61 |

hat |

7 |

0.19% |

|

20 |

bear |

17 |

0.47% |

61 |

moon |

7 |

0.19% |

|

22 |

subject |

16 |

0.44% |

61 |

individu |

7 |

0.19% |

|

22 |

child |

16 |

0.44% |

61 |

behavior |

7 |

0.19% |

|

24 |

folklor |

15 |

0.41% |

61 |

pirat |

7 |

0.19% |

|

24 |

cat |

15 |

0.41% |

61 |

son |

7 |

0.19% |

|

26 |

bedtim |

14 |

0.38% |

61 |

magic |

7 |

0.19% |

|

26 |

poetri |

14 |

0.38% |

68 |

train |

6 |

0.16% |

|

28 |

life |

13 |

0.36% |

68 |

read |

6 |

0.16% |

|

28 |

imagin |

13 |

0.36% |

68 |

autumn |

6 |

0.16% |

|

28 |

school |

13 |

0.36% |

68 |

pumpkin |

6 |

0.16% |

|

28 |

song |

13 |

0.36% |

68 |

bath |

6 |

0.16% |

|

32 |

famili |

12 |

0.33% |

68 |

butterfli |

6 |

0.16% |

|

32 |

natur |

12 |

0.33% |

68 |

dinosaur |

6 |

0.16% |

|

34 |

halloween |

11 |

0.30% |

68 |

social |

6 |

0.16% |

|

34 |

chicken |

11 |

0.30% |

68 |

cloth |

6 |

0.16% |

|

34 |

alphabet |

11 |

0.30% |

68 |

danc |

6 |

0.16% |

|

34 |

mother |

11 |

0.30% |

68 |

dress |

6 |

0.16% |

|

34 |

infanc |

11 |

0.30% |

68 |

easter |

6 |

0.16% |

|

39 |

charact |

10 |

0.27% |

68 |

state |

6 |

0.16% |

|

39 |

babi |

10 |

0.27% |

68 |

unit |

6 |

0.16% |

|

39 |

mice |

10 |

0.27% |

68 |

emot |

6 |

0.16% |

Appendix C

Top Bi-grams: Titles and Abstracts

|

Rank |

Bi-gram |

Freq. |

Rank |

Bi-gram |

Freq. |

|

1 |

picture book |

24 |

18 |

illustrations rhyming |

5 |

|

2 |

rhyming text |

17 |

18 |

letter alphabet |

5 |

|

3 |

young boy |

14 |

18 |

grades k-3 |

5 |

|

4 |

board book |

11 |

18 |

york times |

5 |

|

5 |

full color |

10 |

18 |

one day |

5 |

|

5 |

pete cat |

10 |

18 |

new york |

5 |

|

7 |

simple text |

9 |

18 |

one one |

5 |

|

8 |

young readers |

8 |

30 |

past four |

4 |

|

9 |

many things |

7 |

30 |

times bestseller |

4 |

|

9 |

little girl |

7 |

30 |

stop kissing |

4 |

|

11 |

young children |

6 |

30 |

brown bear |

4 |

|

11 |

ten little |

6 |

30 |

letters alphabet |

4 |

|

11 |

definitely wear |

6 |

30 |

heart like |

4 |

|

11 |

babba zarrah |

6 |

30 |

like zoo |

4 |

|

11 |

ice cream |

6 |

30 |

spin web |

4 |

|

11 |

minerva louise |

6 |

30 |

text reveal |

4 |

|

11 |

wear clothing |

6 |

30 |

new way |

4 |

|

18 |

apple pie |

5 |

30 |

animals definitely |

4 |

|

18 |

magic hat |

5 |

30 |

book celebrates |

4 |

|

18 |

white shoes |

5 |

30 |

minutes past |

4 |

|

18 |

board pages |

5 |

30 |

old lady |

4 |

|

18 |

gingerbread man |

5 |

30 |

old macdonald |

4 |

Appendix D

Top Bi-grams: Subject Terms

|

Rank |

Bi-gram |

Freq. |

Rank |

Bi-gram |

Freq. |

|

1 |

juvenile fiction |

412 |

33 |

fictitious character |

8 |

|

2 |

stories rhyme |

76 |

33 |

fiction dogs |

8 |

|

3 |

juvenile literature |

59 |

33 |

juvenile nonfiction |

8 |

|

4 |

fiction stories |

51 |

33 |

fiction domestic |

8 |

|

5 |

board books |

50 |

38 |

mother child |

7 |

|

6 |

fiction animals |

42 |

38 |

apples juvenile |

7 |

|

7 |

pictorial works |

41 |

38 |

fiction color |

7 |

|

8 |

animals fiction |

38 |

38 |

fiction family |

7 |

|

9 |

works juvenile |

34 |

38 |

fiction imagination |

7 |

|

10 |

animals juvenile |

27 |

38 |

fiction bears |

7 |

|

11 |

humorous stories |

26 |

38 |

child juvenile |

7 |

|

12 |

books specimens |

21 |

38 |

dogs juvenile |

7 |

|

13 |

picture books |

20 |

38 |

fiction mother |

7 |

|

14 |

children's stories |

19 |

38 |

rabbits fiction |

7 |

|

14 |

toy movable |

19 |

38 |

mice fiction |

7 |

|

14 |

fiction humorous |

19 |

38 |

sons fiction |

7 |

|

14 |

movable books |

19 |

38 |

life fiction |

7 |

|

14 |

fiction board |

19 |

38 |

imagination fiction |

7 |

|

14 |

fiction juvenile |

19 |

38 |

color fiction |

7 |

|

20 |

books children |

14 |

53 |

clothing dress |

6 |

|

21 |

fiction children's |

13 |

53 |

united states |

6 |

|

22 |

bedtime fiction |

12 |

53 |

parent child |

6 |

|

23 |

animals infancy |

11 |

53 |

baby books |

6 |

|

23 |

fiction picture |

11 |

53 |

infancy juvenile |

6 |

|

23 |

bears fiction |

11 |

53 |

cats juvenile |

6 |

|

26 |

domestic animals |

10 |

53 |

fiction schools |

6 |

|

27 |

counting juvenile |

9 |

53 |

fiction alphabet |

6 |

|

27 |

fiction counting |

9 |

53 |

fiction friendship |

6 |

|

27 |

chickens fiction |

9 |

53 |

fiction halloween |

6 |

|

27 |

child fiction |

9 |

53 |

fiction social |

6 |

|

27 |

dogs fiction |

9 |

53 |

pirates fiction |

6 |

|

27 |

rhyme juvenile |

9 |

53 |

play fiction |

6 |

|

33 |

children's songs |

8 |

53 |

books juvenile |

6 |