Research Article

Federal Library Utilization of

LibGuides to Disseminate COVID-19 Information

Sarah C. Clarke

Medical Reference Librarian

Darnall Medical Library

Walter Reed National

Military Medical Center

Bethesda, Maryland, United

States of America

Email: Sarah.c.clarke.civ@mail.mil

Emily E. Shohfi

Clinical Medical Librarian

Darnall Medical Library

Walter Reed National

Military Medical Center

Bethesda, Maryland, United

States of America

Email: Emily.e.shohfi.civ@mail.mil

Sharon Han

Engagement Specialist

All of Us National Program

Network of the National

Library of Medicine

University of Iowa

Iowa City, Iowa, United

States of America

Email: Sharon-han@uiowa.edu

Received: 29 July 2021 Accepted: 14 Dec. 2021

![]() 2022 Clarke, Shohfi, and Han. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2022 Clarke, Shohfi, and Han. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30017

Abstract

Objective

–

In winter 2019-2020, the world saw the emergence of coronavirus disease

(COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

(SARS-CoV-2). More than a year later, the pandemic continues with the U.S.

death toll surpassing 550,000. Over the last decade, librarians have increased

their roles in infectious disease outbreak response. However, no existing

literature exists on use of the widely-used library content management

platform, LibGuides, to respond to infectious disease outbreaks. This research

explores how Federal Libraries use LibGuides to distribute COVID-19 information

throughout the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

–

Survey questions were created and peer-reviewed by colleagues. Survey questions

first screened for participant eligibility and collected broad demographic

information to assist in identifying duplicate responses from individual

libraries, then examined the creation, curation, and maintenance of COVID-19

LibGuides. The survey was hosted in Max.gov, a Federal Government data

collection and analysis tool. Invitations to participate in the survey were

sent via email to colleagues and listservs and posted to personal social media

accounts. The survey was made publicly available for three weeks. Collected

data were exported into Excel to clean, quantify, and visualize results. Long

form answers were manually reviewed and tagged thematically.

Results

–

Of the 78 eligible respondents, 42% (n = 33) reported that their library uses

LibGuides to disseminate COVID-19 information; 45% of these respondents said

they spent 10+ hours creating their COVID-19 LibGuide, and 60% of respondents

spent <1 hour a week on maintenance and updates. Most LibGuides were created

in early spring 2020 as the U.S. first saw an uptick in COVID-19 cases. For

marketing purposes, respondents reported using web/internal announcements (75%)

and email (50%) most frequently. All respondents reported inclusion of U.S.

Government resources in their COVID-19 LibGuides, and a majority also included

guidelines, international websites, and databases to inform their user

communities.

Conclusion

–

Some Federal Libraries use LibGuides as a tool to share critical information,

including as a tool for emergency response. Results show libraries tend to

start from scratch and share the same resources, duplicating efforts. To

improve efficiency in LibGuide curation and use of library staff time, one

solution to consider is the creation of a LibGuides template that any Federal

Library can use to quickly set up and adapt an emergency response LibGuide

specifically for their users. Additionally, findings show that libraries are

uncertain of archiving and preservation plans for their guides post-pandemic,

suggesting a need for recommended best practices.

Introduction

In

the winter of 2019-2020, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

(SARS-CoV-2) emerged, creating a new strain of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) (WHO, 2020). People infected with

COVID-19 present varying symptoms and degrees of severity; common

characteristics include coughing, difficulty breathing, fever, and loss of

taste or smell (CDC, 2020a). COVID-19’s

rapid global spread and severity in impacted populations led the World Health

Organization (WHO) to declare the first pandemic caused by a coronavirus on

March 11, 2020 (Adhanom Ghebreyesus, 2020).

Early official reports of COVID-19 cases in the United States emerged in

January 2020, and cases have exceeded 32.5 million as of May 12, 2021 (CDC, 2020b; Stein, 2020). Following examples

set from previous management of respiratory disease outbreaks, such as Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS, 2012)

and severe acute respiratory

syndrome (SARS, 2003), public health officials recommended frequent

handwashing and avoiding close contact with infected individuals to reduce

transmission rates (Lai et al., 2020). In

the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provided further

guidance to slow virus transmission by limiting mass gatherings, closing

schools and non-essential businesses, issuing stay-at-home orders, and wearing

cloth face coverings in public areas (Schuchat,

2020). As COVID-19 cases continue in the U.S., mitigation and monitoring

strategies remain priorities for many Government and public health

professionals.

Literature Review

Over

the last decade, libraries have increased their roles in infectious disease

outbreak response. During the 2014-2016 Ebola

outbreak, librarians were involved with providing information and website support

to affected African countries (Jackson, 2014;

Landgraf, 2014). At the U.S. Federal level, the Disaster Information

Management Research Center (DIMRC) at the National Library of Medicine (NLM)

created a special health topic page, “Ebola Outbreak 2014: Information

Resources” (Love et al., 2015). DIMRC

also curated pages for pandemic influenza, Zika, and the 2018 Ebola outbreak.

Through the Medical Library Association (MLA), librarians can earn a Disaster

Information Specialization, which provides knowledge of disaster preparedness

and response structure at varying levels of Government and prepares them to

assist in the response of various disasters, including infectious disease

outbreaks (MLA). There is no existing

literature focused on the use of the widely-used library content management and

curation platform, LibGuides, to respond to

information needs during infectious disease outbreaks. However, during

the current COVID-19 pandemic, Springshare, the creator of LibGuides,

highlighted several examples of COVID-19 specialty pages on their blog (Creech, 2020; Talia, 2020). A recently

published paper examines the roles librarians fill in response to COVID-19 and

determined there are three dimensions of librarian support: to promote consumer

level information for preventive measures, support researchers and/or faculty

in their varying needs, and maintain core-needs of patrons (Ali & Gatiti, 2020). LibGuides is an acceptable platform to meet these objectives.

LibGuides

is an annually licensed product designed specifically for libraries. The

purchased system serves as the primary web presence basis for many libraries,

helping library staff curate knowledge, share information, and organize subject

specific resources (Springshare, 2020b).

As of May 2021, LibGuides were employed at 6,100 institutions across 82

countries, with nearly 800,000 guides created by more than 130,000 library

staff (Springshare, 2021). Springshare is

unable to provide a complete list or data regarding Federal Library customers

(Ware, 2021). The platform is known for its ease of use and navigation, as well

as its reusability for resources. It is mobile-optimized and available without

institutional log-in. It provides automatic link checking and easily captures

usage statistics for entire LibGuides or individual pages (Leibiger & Aldrich, 2013). Because of its

ease of set-up and external access, libraries that use LibGuides can quickly

add or pivot content to meet user demands without relying on intranet

administrators, therefore removing lengthy wait times. However, some barriers

may exist to those acquiring LibGuides, such as budget constraints, staffing,

or IT concerns surrounding security.

The

LibGuides Community allows for libraries to choose to share all or part of

their guides for other libraries to reuse. Customizing a reused guide will not

affect the original guide. When a library chooses to use this function, the

original guide owner will be notified. Best practices call for obtaining

permission before copying a guide (Springshare

2020a). The system allows for private and hidden pages, which many use

for content pages under development, or those with more sensitive information

not intended for public audiences. Customization is important as it allows

libraries to highlight licensed resources accessible to their patron base.

Aims

Multiple

U.S. Federal Libraries utilize LibGuides, many of which are publicly available.

With this in mind, we set out to understand how Federal Libraries use LibGuides

to distribute COVID-19 information throughout the course of the pandemic. The

decision to restrict the scope of research to Federal Libraries was inspired by

the literature gap in Federal Library response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Currently published literature regarding library response to the pandemic was

heavily focused on public and academic library response. Similarly, a gap in

the literature exists with regards to Federal Library utilization of LibGuides.

Due to security, some Federal Libraries must create and maintain their

LibGuides privately to protect their organizational mission. Surveying this niche

population begins a conversation surrounding which types of Federal Libraries

utilize this tool. Learning more about the creation, curation, and maintenance

of COVID-19 LibGuides will shed light on response effort capabilities within

Federal Libraries and help determine future best practices for streamlining the

urgent information-sharing process, should there be future pandemics or other

emergencies.

Methods

Survey Design

In

this qualitative study, we selected a written survey method for assessing the

Federal Library sample population on their practices in utilizing LibGuides for

distribution of COVID-19 information. Surveys are common in library research,

and for our purposes, were utilized for conveniently and safely obtaining

information from a sizable, wide-spread sample of Federal Libraries amid a

global pandemic. They are especially useful in eliciting information about

attitudes that “are otherwise difficult to measure using observational

techniques” (Glasow, 2005). Survey

questions were designed based on research objectives and demographic

information of interest. The final survey included 20 questions. Two questions

screened for participant eligibility for the study, and three questions

collected broad demographic information used to identify duplicate responses

from individual libraries. The remaining questions focused on the creation,

curation and design, and engagement and preservation of COVID-related LibGuides

in Federal Libraries. These topics were selected to obtain a comprehensive overview

of the continuum of LibGuide activities related to the pandemic. Questions were

externally reviewed by colleagues and key stakeholders and revised based on

feedback. The survey was submitted for creation to MAX.gov, a Federal

Government data collection and analysis tool, for hosting. MAX.gov

administrators created the survey and made revisions before survey

dissemination. MAX Survey allows for conditional logic and used a generic

survey link. Survey questions can be viewed in Appendix A.

Survey Distribution

The

written survey was distributed electronically. Email, forums, and social media

were used to solicit responses from Federal librarians. Emails or forum posts

were sent to Federal librarian groups, such as FEDLIB, a listserv moderated by

the Library of Congress, and other Federal librarianship interest groups within

national library associations, including the Medical Library Association,

Special Libraries Association, and the American Library Association. These

groups are commonly used to connect with Federal librarians and are heavily

utilized to recruit voluntary survey participants. The authors’ personal social

media accounts on Facebook and Twitter were also used to invite participants.

Posts used the following hashtags to promote the study: #medlibs,

#librarytwitter, #covidlibrary, #librarians, #LibGuides, and #federallibraries.

The

initial timeframe for responses was two weeks, beginning September 23, 2020,

and was extended an additional week until October 16, 2020. Three rounds of

reminders were engaged to elicit voluntary survey participants.

At

the beginning of the survey, respondents were asked a screener question gauging

if they were a federal librarian. If they responded no, the survey would

automatically end.

Data Collection, Cleaning, and Analysis

Survey

responses were collected online and data was stored securely through Max.gov’s MAX Survey. Survey results were exported in XLSX

format view using MAX Analytics.

Results

data were de-identified, cleaned, quantified, and visualized using Excel. Long

form answers were manually reviewed and tagged based on consistent themes that

appeared in responses; we reviewed these themes as a group. Themes are further

explained in the Results and Discussion. The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in

Open Source Framework (OSF) at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/SWF34 (Clarke, Han,

& Shohfi, 2021).

Results

Use and

Creation

The survey had 96 library respondents. Eighteen

respondents (19%) were immediately screened out for eligibility, as they

selected that they did not work in a Federal Library. Based on the broad

demographic responses provided, we did not identify a single library as having

multiple staff respondents. Of the remaining 78 respondents, 33 (42%) reported

that their library uses LibGuides. One-third (n=11) of respondents reporting

LibGuide use had publicly viewable LibGuide pages, 7 (21%) had LibGuides set to

private access, and 2 (6%) had a mix of both private and public pages.

When surveyed if

their library utilized LibGuides to disseminate COVID-19 information, 20 (61%)

respondents utilizing LibGuides stated yes, 12 (36%) stated no, and one was

unsure. Ten respondents explained with free text why their institutions did not

share COVID-19 information in their LibGuides. Of these, 80% of the respondents

elucidated that this information was out of scope for their library’s services,

or the duty belonged to another department within their agency. The remaining

respondents could not share COVID-19 information due to logistical reasons

including staffing constraints.

Thirteen

respondents had primary responsibility over their library’s COVID-19 LibGuide

page(s), while five shared responsibility. 2 respondents did not have

responsibility over their library’s COVID-19 LibGuide page(s) but were able to

provide details about what their guides contained.

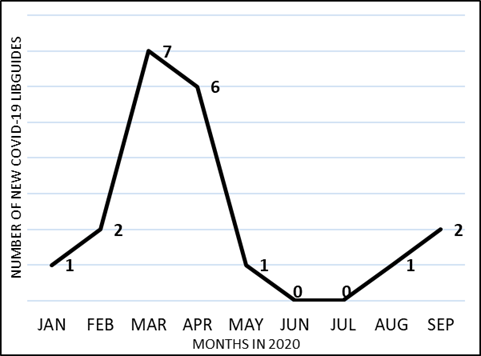

Figure 1

Months which respondents

reported creation of their COVID-19 LibGuides in Federal Libraries.

Figure 2

Reported time spent on

initial content curation and ongoing weekly maintenance.

According to responses, the earliest

Federal COVID-19 LibGuide was created in January 2020 (Figure 1). 7 COVID-19

LibGuides were created in March 2020, making it the most popular month for

creation. COVID-19 LibGuides creation continued during data collection for this

study, which began in September 2020.

The estimated

initial time spent on the creation/curation of COVID-19 LibGuide information

varied amongst respondents (Figure 2). While one respondent spent under an hour

and two spent 1-5 hours on initial LibGuide creation, the majority of

respondents spent either 6-10 hours (40%) or more than ten hours (45%). After

the initial set-up and curation of resources, respondents reported less time

investment engaging in weekly updates and maintenance. Twelve respondents

estimated they spent under an hour each week updating COVID-19 LibGuide

information, and six respondents spent an estimate of 1-5 hours. One respondent

spent between 6-10 hours, and one respondent spent over ten hours.

Respondents

using LibGuides had varied audiences for COVID-19 information. The number of

respondents who selected specific audiences (count and %) are represented in

Table 1. Respondents were able to select more than one audience type for their

COVID-19 LibGuide while responding to this question on the survey. Responses

indicated many had overlapping or multiple audiences.

Table 1

Intended Audiences for COVID-19 LibGuides as Selected by Respondents (N

= 20)

|

Intended Audience |

Number of Respondents Included (N = 20) |

% of Respondents Included |

|

Health Professionals |

9 |

18.8% |

|

Military |

7 |

14.6% |

|

Government |

7 |

14.6% |

|

Library Staff |

6 |

12.5% |

|

Researchers |

5 |

10.4% |

|

Students |

5 |

10.4% |

|

Administration |

4 |

8.3% |

|

Other |

3 |

6.3% |

|

Public |

1 |

2.1% |

|

Patients |

1 |

2.1% |

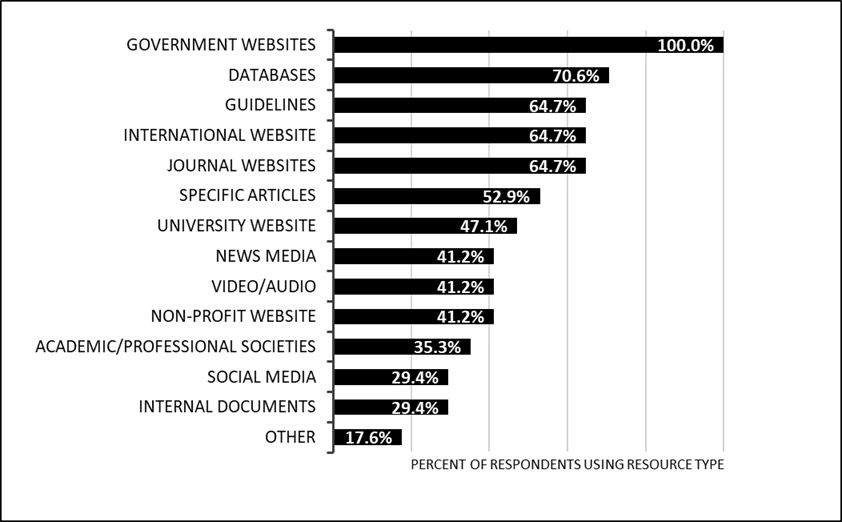

Figure 3

Types of resources used in COVID-19

LibGuides as reported by respondents.

Curation, Organization, and

Marketing

As

seen in Figure 3, respondents shared a wide variety of resources on their

LibGuides. Government websites were included in all Federal LibGuides, and

databases, guidelines, international websites, journal websites, and specific

articles were included in more than half of respondents’ COVID-19 LibGuides.

Less than a third of respondents indicated they included social media or

internal documents on their LibGuides.

Regarding

reuse, only 3 respondents reused all or part of another library’s COVID-19

LibGuide. Thirteen respondents did not reuse all or part of another library’s

COVID-19 LibGuide, instead creating and curating their content from scratch. 1

respondent granted reuse permission to multiple libraries to reuse their

COVID-19 LibGuide, 4 did not grant reuse permission to other libraries from

requests received, and 10 were not asked for their LibGuide to be reused.

There were 12 free-text responses on

how libraries determined sources most applicable and appropriate for their

COVID-19 LibGuides. To determine which sources were most appropriate for a

LibGuide, respondents reported consideration of the following: quality (7

responses), user feedback/focus (5), what others were doing (4), convenience

(2), access/availability (2), and current topics (1).

One respondent reported great freedom

and latitude in decision making, focusing content curation and resources based

on conversations and feedback with their patron base and communication from

leadership. They also were able to respond to needs based on common questions

or ongoing topics of conversation within their organization. Another respondent

sought authoritative information based on recommendations from healthcare

professionals.

According to free-text responses, some

respondents (greater than four) looked primarily at user feedback, or focused

on their user base, while others looked more toward what other libraries were

doing to guide decision-making in source curation. Both groups sought to have

current topics and up-to-date information. In several instances, respondents

looked to other individual information professionals’ pages, such as other

Federal Health Libraries, or to institutions that took a lead in information

curation during the early part of the pandemic (e.g., Johns Hopkins University)

to guide their content curation. Some respondents sought broad information,

rather than in-house content, while others specifically tried to tailor their

pages to local resources and internal guidance.

At least two respondents mentioned

convenience, access, and availability of resources being a deciding factor.

Some of these were resources sent to them by their agency or easily copied or

downloaded from another Federal Agency. Others used resources that were open

access, or their content curation was driven by what vendors were providing

through their license agreements.

Across the board, respondents agreed

quality of information was critical in their source curation. Peer-reviewed and

authoritative sources, such as Federal Government agencies (e.g., CDC and NLM)

were cited often. There was also a focus on finding non-biased coverage of

information and looking to leading institutions in the pandemic for clear

direction.

Twelve respondents reported four different ways of

organizing their content within their LibGuides, which included: by content

(7), resource type (6), audience (4), and chronologically (1). Content included

references to specific information provided by resources. While most mentions

of content were specific to the spread and response to COVID-19 (“disease

tracking” and “Local Information”), at least one respondent also included

information on teleworking (“teleworking during COVID tips”). Resource type

included mentions of different publication formats, although only two

respondents provided specifics (“special reports, peer-reviewed literature,

preprints”; “databases, and then other research tools”). Several respondents

mentioned creating resource pages for specific users, particularly for medical

staff (“nurses, physicians”) and patients. Only one respondent mentioned

ordering information chronologically so the most current information would

precede older information.

Sixteen

respondents provided free text answers regarding marketing their new COVID-19

LibGuide pages. To market these guides, respondents implemented the following:

web/internal announcements (12), email (9), social media (2), targeted audience

messaging (3), and word of mouth (1). All but one free-text response relied on

electronic means of marketing. Most

respondents noted using a combination of two marketing practices (9), and one

respondent utilized a combination of three. Included in the web/internal

announcements category were agency intranets, web notices, newsletters, webpage

announcements, blogs, or online message boards. Social media platforms

mentioned in the responses included Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and a more

general “social media channels.” Targeted audience messaging referred to

marketing towards leadership, relevant department heads, or specific students.

While the question referred to the marketing of new LibGuide pages, one

respondent provided that they had not “been diligent about updates.”

Engagement, Quality, and Future Plans

Eleven

respondents provided free text responses discussing how they measure

engagement, including feedback, of their COVID-19 LibGuide page(s). Eight

respondents (73%) utilized Springshare’s integrated LibGuide web analytics,

five respondents (45%) engaged patrons for feedback directly, and one library

reported not currently measuring engagement. Respondents using LibGuide’s web analytics mentioned usage statistics or page

view statistics, or more broadly referenced Springshare statistics. One

respondent noted that “for a few months [the COVID-19 LibGuide] was our most

visited LibGuide page.” Personal feedback included responses such as e-mails, phone

calls, narratives, direct contact, and patron engagement. One respondent shared

that their library tries “to engage our patrons and encourage them to submit

relevant content/resources. If they provide any input, it is discussed and

responded to.”

To

measure the quality of COVID-19 LibGuides, respondents relied on patron

feedback (15%), analytics (7.7%), and peer/self-review (38%). Three (23%)

respondents were unsure or did not implement any quality measures. Several

respondents specifically mention taking audience needs and expectations into

consideration, and one respondent mentioned directly responding to input if

provided. Peer/self-review described by free-text responses explicitly

mentioned personal expectations or group curation efforts to produce a quality

LibGuide (“personal high standard”; “curated by a team”). Only one respondent

mentioned continuous review of information in order to remove “incorrect or

outdated links.” One respondent also used analytics, such as site visits, as a

measure for quality.

A

final question asked respondents to describe their plans for the COVID-19

LibGuide once the pandemic ends. Post-pandemic, six respondents planned to

maintain and regularly update their COVID-19 LibGuides, three planned to keep

the guides viewable but no longer update, one planned to archive the page, and

seven were unsure or had no plans at the time of the survey.

Discussion

Our

findings show that, of the Federal Library respondents who used LibGuides, over

half (61%) were using LibGuides to share COVID-19-related information. This

value indicates that LibGuides were actively being used to disseminate critical

public health information in a timely manner. It is important to note that of

the respondents who used LibGuides, those who did not use them to disseminate

COVID-19 information were often constrained by job responsibilities or another

agency department having authority over COVID-19 information dissemination.

At

the beginning of the pandemic, the Wellcome Trust

initiated a statement calling on funders, researchers, and publishers to ensure

that relevant data is openly accessible to ensure a prompt health response

globally (Trust, 2020). Because of this

collaborative statement, many major publishers or journals created open access

COVID-19 resources and marketed them to their library customers. Such resources

were often used (64.7%) in Federal Library COVID-19 LibGuides. Such a statement

ensures broad access to crucial information regardless of existing licenses.

More libraries, regardless of their purchased content or operating budget, were

able to share timely articles on COVID-19.

There was heterogeneity with respect to the degree to which

Federal Libraries had control over their content and where the responsibility

lay for disseminating pandemic information. Respondents varied in accessibility

to page viewing, time spent curating and updating information, best practices

for measuring quality of the information provided, and plans for archiving the

information post-pandemic.

To market COVID-19 LibGuides, respondents used a variety of

techniques throughout the pandemic. Most utilized internal or web announcements

or email to reach their target audiences, whereas some sent targeted messages

to their audiences or had to rely on word of mouth. Of note, at the beginning

of the pandemic, many libraries transitioned to virtual services, at least

temporarily (American Library Association, 2020),

and some lost access to their normal avenues for marketing in this transition.

While some libraries were able to continue with marketing on agency intranet

sites, others may have needed to rely more heavily on email

communication to the agency at large or to smaller specific audiences to spread

information. Additionally, libraries may have relied more heavily on word of

mouth or non-traditional platforms such as social media sites to inform their

customer base, given the widespread access limitations the Federal workforce

experienced during the work-from-home transition for non-essential personnel in

the early months of the pandemic.

The

number of COVID-19 LibGuides created over time appears to reflect the early

spread of the disease and widespread uncertainty beginning in spring 2020. For

example, the highest number of COVID-19 LibGuides were created in March (7) and

April (6), correlating with mass telework options made available to Government

agencies via the Office of Personnel Management (Office of Personnel

Management, 2021). As the pandemic continued, respondents were still creating

new COVID-19 LibGuides in fall 2020. It is unclear as to why respondents

specifically created LibGuides six months or more into the pandemic, as the

survey did not ask for respondents to provide rationale for creation.

Researching,

reviewing, compiling, building, organizing, and formatting a new LibGuide on an

emergent topic from scratch can be daunting and time-consuming; 40% of

respondents spent 6-10 hours and 45% spent more than ten hours on LibGuide

creation. Survey results, paired

with free text responses from

respondents about their curation process, suggest that the bulk of the curation and creation time was spent reviewing and

selecting resources. To

reduce the time burden and labor of this task, three respondents reused all or

part of another library’s COVID-19 LibGuides. And while audience types varied

widely, types of resources included in a COVID-19 LibGuide had evident overlap.

For example, Government websites were present in all respondent LibGuides,

acting as a baseline resource across varying audience types. In future

pandemics or public health crises, libraries with similar audience bases can

save time and effort perhaps by collaborating to create a LibGuide with

standard information as a starting point to share with one another.

Creating

such a collaborative effort would involve proactively locating similarly scoped

libraries, contacting them for interest, and creating a collaborative plan for

domain of responsibility. Depending on how many libraries are participating,

tasks like researching, reviewing, and compiling resources at the broadest

level appropriate could be assigned. Furthermore, libraries or librarians with

the greatest collective expertise could build, organize, and format the content

in LibGuides. All libraries participating in this collaborative effort could

have permission to reuse and edit the LibGuide as they saw fit for their

individual library. Benefits of taking part in such a collaboration include

saved time and effort of library staff, both of which can impact personnel

budgets. The LibGuide could also be peer-reviewed, as multiple library staff

with different levels and areas of expertise could work collaboratively while

engaging in constructive feedback. An

additional benefit could be giving back to the library science field and

allowing these LibGuides to be available for reuse by libraries outside of the

Federal Government who may not have the staff or means to create their own.

Best

practices in LibGuide design for specific audiences cannot be determined from

this survey, as most respondents serve a wide variety of military, civilian,

internal, and/or external audiences. However, general guidelines for where to

start finding relevant public health information for the broadest audience

could be informed by the most common resources used by respondents, to include

government websites, databases, guidelines, international organizations, and

journal websites. Knowing where to start reviewing resources to curate could

then potentially reduce the initial time and resource burden to create these

guides.

Limitations

Due to the narrow scope of our research question and audience,

addressing the use of LibGuides for COVID-19 information in only Federal

Libraries, we may have missed other findings from the general or specialized

library populations (medical, academic, public, research, law, etc.) that also

contribute to best practices for disseminating information. Additionally, we

only explored the use of LibGuides, and we recognize that while this is a

broadly-used platform, many Federal Libraries do not use it and may be

providing curated content and library services related to the pandemic in other

ways. While this focus was chosen purposefully given the dramatically different

relationships that exist between Federal Libraries and the populations they

serve, and the broader library community and their patrons, it may still have

excluded important findings. With these limitations in mind, this study can serve as a springboard for future inquiries

into the literature and studies in the library community for pandemic planning,

preparedness, and response.

Conclusion

The

ability to quickly disseminate information is imperative during a public health

crisis, let alone a global pandemic. The emergence of COVID-19 put the U.S.

health response to the test as organizations at every level scrambled to

provide answers to an ever-growing list of questions. Federal Libraries found

themselves in a unique position of providing services remotely while also

attempting to curate and provide quality COVID-19 resources for their diverse

patrons. This research surveyed how Federal Libraries used LibGuides to

distribute COVID-19 information throughout the course of the pandemic. Federal

Libraries began publishing their COVID-19 LibGuides as early as January 2020,

when the U.S. announced the first case, with a spike in their creation in March

2020 as states began issuing guidance on lockdowns. Creating a LibGuide is a

time consuming process, and creating one on an ever-changing and rapidly

growing topic requires dedicated time for consistent maintenance as information

evolves. Tracking engagement, eliciting and considering feedback, and

determining quality of resources all helped shape COVID-19 LibGuide content. Results

highlight the potential for future collaborative opportunities to streamline

Federal Library public health response. This study provides valuable insight

into the information-sharing process, which will help reduce the burden and

save time for future libraries should there be another public health emergency.

Disclaimer

The

research protocol and online survey used in this study were approved by the

Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC) Institutional Review

Board (IRB): WRNMMC-EDO-2020-0535, 927350; and the Defense Health Agency:

Department of Defense (DoD) Survey License Exemption (#9)-Exempt #0053.

This

research was supported in part by an appointment to the National Library of

Medicine (NLM) Research Participation Program. This program is administered by

the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency

agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and the National Library

of Medicine (NLM). ORISE is managed by ORAU under DOE contract number DE-SC0014664.

All opinions expressed in this paper are the author's and do not necessarily

reflect the policies and views of NLM, DOE, or ORAU/ORISE.

The

views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy

of the Department of the Army/Navy/Air Force, Department of Defense, or U.S.

Government.

Author Contributions

Sarah Clarke:

Conceptualization (equal), Formal analysis (supporting), Investigation (equal),

Methodology (equal), Project administration (lead), Visualization (supporting),

Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal) Emily Shohfi:

Conceptualization (equal), Formal analysis (supporting), Investigation (equal),

Methodology (equal), Project administration (supporting), Visualization (lead),

Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal) Sharon Han: Conceptualization (equal), Formal

analysis (lead), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Project

administration (supporting), Visualization (supporting), Writing – original

draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal)

References

Adhanom Ghebreyesus, T. (2020). WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on

COVID-19—11 March 2020 [Interview]. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020

Ali, M. Y., & Gatiti, P. (2020). The COVID-19

(coronavirus) pandemic: reflections on the roles of librarians and information

professionals. Health Information &

Libraries Journal, 37(2),

158-162. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12307

American Library Association. (2020). Libraries respond: COVID-19 survey. http://www.ala.org/tools/covid/libraries-respond-covid-19-survey

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020a). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) –

Symptoms. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved May 8,

2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020b). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention. Retrieved May 7, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html

Clarke, S. C., Han, S., & Shohfi, E. E.

(2021). Federal Library utilization of

LibGuides to disseminate COVID-19 information survey data [Data set]. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/SWF34

Creech, L. (2020, April 17). Supporting patrons during the

pandemic using Springshare tools. The Springy Share. https://blog.springshare.com/2020/04/17/supporting-patrons-during-the-pandemic-using-springshare-tools/

Glasow, P. A. (2005). Fundamentals

of survey research methodology. The MITRE Corporation. https://www.mitre.org/sites/default/files/pdf/05_0638.pdf

Jackson, C. (2014, October 22). Chapel Hill librarians

helping Ebola fight in West Africa. North

Carolina Public Radio. https://www.wunc.org/post/chapel-hill-librarians-helping-ebola-fight-west-africa

Lai, C. C., Shih, T. P., Ko, W. C., Tang, H. J., &

Hsueh, P. R. (2020). Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

(SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): The epidemic and the

challenges. International Journal of

Antimicrobial Agents, 55(3),

105924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924

Landgraf, G. (2014, October 3). Tracking Ebola in Liberia. American Libraries. https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2014/10/03/tracking-ebola-in-liberia/

Leibiger, C. A., & Aldrich, A. W. (2013). “The Mother of All LibGuides”: Applying

principles of communication and network theory in LibGuide design. Imagine,

Innovate, Inspire: Proceedings of the ACRL 2013 Conference, Indianapolis, IN,

United States. https://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/conferences/confsandpreconfs/2013/papers/LeibigerAldrich_Mother.pdf

Love, C. B., Arnesen, S. J., & Phillips, S. J. (2015).

Ebola outbreak response: the role of information resources and the National

Library of Medicine. Disaster Medicine

and Public Health Preparedness, 9(1),

82-85. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2014.108

United States Office of Personnel Management. (2021,

February 19). Policy, data, Oversight:

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). United States Office of Personnel

Management. Retrieved June 24, 2021, from https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/covid-19/

Medical Library Association (2021). Disaster Information Specialization. Medical Library Association.

Retrieved January 1, 2021, from https://www.mlanet.org/page/disaster-information-specialization

Schuchat, A. (2020). Public health response to the

initiation and spread of pandemic COVID-19 in the United States, February

24-April 21, 2020. Morbidity and

Mortality Weekly Report, 69(18),

551-556. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6918e2

Springshare. (2020a). Guides:

Create or copy a guide. Springshare. Retrieved January 1, 2021, from https://ask.springshare.com/libguides/faq/770#section2

Springshare. (2020b). LibGuides:

Curate resources, share knowledge, publish content. Springshare. Retrieved

January 27, 2021, from https://www.springshare.com/libguides/

Springshare. (2021). LibGuides

community. Springshare. Retrieved January 27, 2021, from https://community.libguides.com/

Stein, R. (2020, January 24). 2nd U.S. Case Of Wuhan

coronavirus confirmed. National Public

Radio. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/01/24/799208865/a-second-u-s-case-of-wuhan-coronavirus-is-confirmed

Talia. (2020, March 16). Tips & tricks for the

remote-First World. The Springy Share.

https://blog.springshare.com/2020/03/16/tips-tricks-for-the-remote-first-world/

Ware, D. (2021). Federal Libraries using LibGuides from

Springshare! In E. Shohfi (Ed.). Personal Email Communication.

Wellcome Trust. (2020, January 31). Sharing research data and findings relevant to the novel coronavirus

(COVID-19) outbreak [Press release]. https://wellcome.org/press-release/sharing-research-data-and-findings-relevant-novel-coronavirus-ncov-outbreak

World Health Organization. (2020). Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it.

World Health Organization. Retrieved May 8, 2020, from https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it

Appendix A

Survey Questions

Section

1. LibGuide Creation

1.

Does

your library use LibGuides?

o

Yes

o

No

2.

Are

your LibGuides publicly viewable?

o

Yes

o

No

o

Some

pages

3.

Has

your library used LibGuides to disseminate COVID-19 information?

o

Yes

o

No

o

Unsure

4.

If

no to Question 3, why not?

o

[Free

text]

5.

Do

you have primary responsibility over COVID-19 content on your LibGuides?

o

Yes

o

No

o

Shared

6.

What

month did your library begin curating COVID-19 information on your LibGuide?

o

December

2019

o

January

2020

o

February

2020

o

March

2020

o

April

2020

o

May

2020

o

June

2020

o

Unsure

7.

Who

is the intended audience(s) for your COVID-19 LibGuide. Please select all that

apply.

o

General

Public

o

Health

Professionals

o

Military

o

Researchers

o

Administrators

o

Government

o

Patients

o

Students

o

Library

staff

o

Other:

[free text]

8.

Estimate

how much time (in hours) was spent on the initial creation/curation of COVID-19

LibGuide information?

o

<1

hour

o

1-5

hours

o

6-10

hours

o

10+

hours

9.

Estimate

how much time (in hours) is spent each week updating COVID-19 LibGuide

information?

o

<1

hour

o

1-5

hours

o

6-10

hours

o

10+

hours

Section

2. LibGuide Curation and Design

10.

Which

of the following information resource types are linked to or included in your

LibGuides? Please select all that apply.

o

Databases

o

Journal

Websites

o

Specific

Articles

o

Government

Websites

o

International

Websites

o

Non-profit

Websites

o

University

Websites

o

Video/Audio

o

Internal

Documents

o

Guidelines

o

Academic/Professional

Societies

o

News

Media

o

Social

Media

o

Other:

[free text]

11.

How

did you determine which sources were most appropriate for your LibGuide?

o

[Free

text]

12.

Describe

how you organized the content within your COVID-19 LibGuide.

o

[Free

text]

13.

Did

your library reuse any part of another library’s existing COVID-19 related

LibGuide?

o

Yes

- Reused all or part of another library’s COVID-19 LibGuide

o

No

- Did not reuse another library’s COVID-19 LibGuide

o

Unsure

14.

Did

your library grant permission to another library to reuse your COVID-19 related

LibGuide?

o

Yes

– We granted reuse permission

o

No

– We did not grant reuse permission

o

N/A

– No library asked permission for reuse

o

Unsure

Section

3. LibGuide Engagement and Preservation

15.

How

does your library market new LibGuide pages (related to COVID-19) to patrons?

o

[Free

text]

16.

How

do you measure engagement, such as feedback, of your COVID-19 LibGuide?

o

[Free

text]

17.

How

do you measure quality of your COVID-19 LibGuide?

o

[Free

text]

18.

Currently,

what are your plans for this page post-pandemic?

o

Maintain/update

regularly

o

Viewable,

but no longer updated

o

Archive

it (offline or as a hidden/unpublished page)

o

Not

sure/no plans

o

Other:

[free text]

Section

4. Demographic Questions

19.

Which

federal government agency/department/division does your library serve?

o

[Free

text]

20.

What

is the name of your library? (This information will not be shared – it’s to

ensure we don’t record duplicate information)

o

[Free

text]

21.

What

is your library’s zip code? (This information will not be shared – it’s to ensure we

don’t record duplicate information)

o

[Free

text]