Research Article

Charting the Future of the Ginans: Needs and Expectations of the Ismaili Youth in the Western Diaspora

Karim Tharani

Information Technology Librarian

University of Saskatchewan Library

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada

Email: karim.tharani@usask.ca

Received: 8 Oct. 2021 Accepted: 23 Feb. 2022

![]() 2022 Tharani. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2022 Tharani. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30055

Abstract

Objective – The heritage of ginans of the Nizari

Ismaili community comprises hymn-like poems in various Indic dialects that were

transmitted orally. Despite originating in the Indian subcontinent, the ginans

continue to be cherished by the community in the Western diaspora. As part of a

study at the University of Saskatchewan, an online survey of the Ismaili

community was conducted in 2020 to gather sentiments toward the ginans in the

Western diaspora. This article presents the results of the survey to explore

the future of the ginans from the perspective of the English-speaking Ismaili

community members.

Methods – An online survey was developed to solicit the needs

of the global Ismaili community using convenience sampling. The survey

attracted 515 participants from over 20 countries around the world. The

English-speaking members of the Ismaili community between 18 to 44 years of age

living in Western countries were designated as the target group for this

study. The survey responses of the target group (n = 71) were then benchmarked

against all other respondents categorized as the general group (n =

444).

Results –

Overall, 85% of the respondents of the survey were from the diaspora and 15%

were from the countries of South Asia including India, Pakistan, and

Bangladesh. The survey found that 97% of the target group respondents preferred

English materials for learning and understanding the ginans compared to 91% in

the general group. Having access to online ginan materials was expressed as a

dire need by respondents in the two groups. The survey also revealed that over

90% of the respondents preferred to access private and external ginan websites

rather than the official community institutional websites. In addition, the

survey validated the unified expectations of the community to see ginans become

an educational and scholarly priority of its institutions.

Conclusion – Based on the

survey results, it can be concluded that the respondents in the target group are educated citizens of

English-speaking countries and regard the heritage of ginans to be an important

part of their lives. They value the emotive and performative aspects of the

tradition that help them express their devotion and solidarity to the Ismaili

faith and community. They remain highly concerned about the future of the

ginans and fear that the teachings of the ginans may be lost due to lack of

attention and action by the community institutions. The development and

dissemination of curriculum-based educational programs and resources for the

ginans emerged as the most urgent and unmet expectation among the survey

respondents. The article also identifies actions that the community

institutions can take to ensure continued transmission and preservation of the

ginans in the Western diaspora.

Introduction

The word “ginan”

is a derivative of the Sanskrit term jnan,

which means knowledge or gnosis. In the context of the Nizari

Ismaili community, the term is used for the community’s collection of gnostic

hymn-like poems. The religious corpus of the ginans comprises some 1,000

individual works composed primarily using Indo-Aryan dialects with loanwords

from Perso-Arabic languages. While the ginans originated in the Indian

subcontinent, the Ismaili community is now a global and culturally diverse

community living in over 25 countries around the world (The Ismaili, 2022).

The emotive

tunes of the ginans continue to be cherished by the community members in the

Western diaspora, particularly those who come from the Indian subcontinent

lineage commonly known as Khojas. Due to the language barrier, however,

the teachings of the ginans remain inaccessible to the English-speaking community

members born and raised in the Western diaspora. This issue is further

compounded by the inaction of the community institutions to develop and

disseminate educational resources for the motivated community youth interested

in learning about the teachings of the ginans. Failing to attend to the needs

and expectations of the youth – who are ultimately responsible for carrying

these traditions forward – may result in the loss of the tradition altogether.

To address this lacuna and explore the future of the

ginans in the digital age, an online

survey was conducted in 2020 to gather and analyze the needs and expectations

of the Ismaili community members interested in the ginans from across the

globe. The survey was administered independently at the University of

Saskatchewan, which currently hosts the searchable online ginan portal called Ginan

Central. Following a brief review of the history of the community and the

corpus of ginans, this article presents the results of the survey. The insights

from the survey results inform the discussion on the future of the ginans in

the Western diaspora.

Literature Review

Today’s digital age presents unprecedented

opportunities for ethnocultural communities to teach and transmit their

knowledge in ways that were not possible in the print era. With information technology becoming an essential enabler for learners

in Western countries, this study is based on the premise that the successive

generations of the Ismaili community expect to engage with the ginans online

and on-demand. Thus, the use of information technology in

conjunction with traditional teaching can enhance motivation and engagement of

the community youth, which in turn can ensure the long-term viability of the

ginans in the Western diaspora.

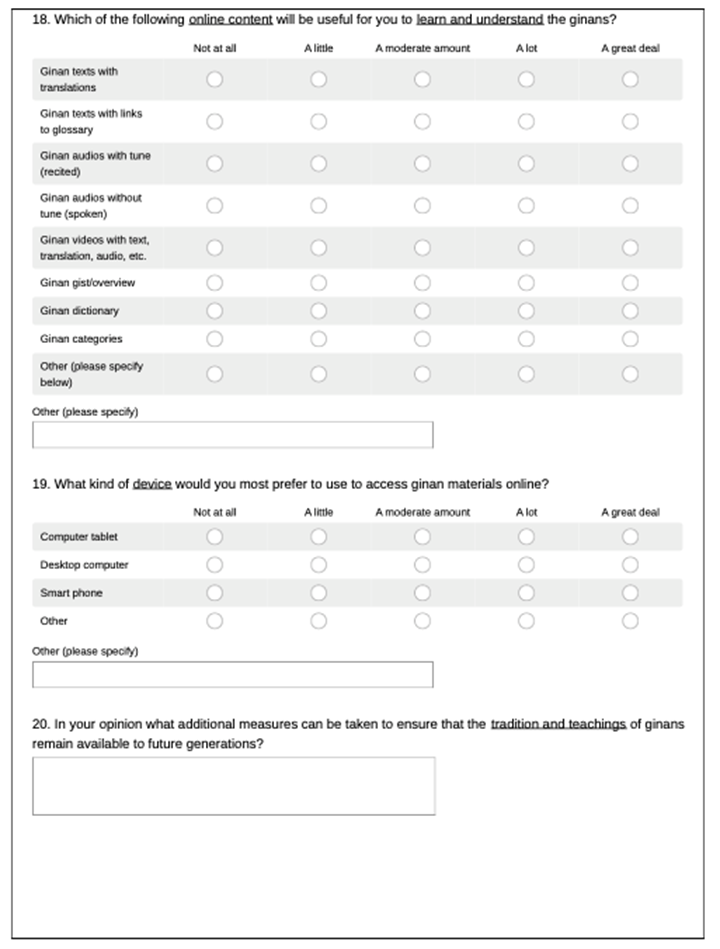

This research utilizes the e-learning theoretical

framework which identifies three theoretical dimensions of an effective

e-learning system (Aparicio et al., 2016). These dimensions include people,

technology, and services. The people dimension defines various roles

that stakeholders may have in an e-learning system, such as learners, content

providers, educators, etc. The technology dimension of an e-learning

system serves as an interface to communicate and connect users with the content

curated for learning activities. The services dimension of an e-learning

system encapsulates the pedagogical models and instructional strategies that

guide the design and development of the e-learning system.

In the context of this study of the Ismaili

community and its tradition of the ginans, the e-learning system framework is

applied by identifying community learners (representing the people dimension)

whose needs and expectations to engage with the ginans online (i.e., the

technology dimension) must be gathered and analyzed to develop effective

curriculum and instruction (manifesting the services dimension). This study

assumes that understanding the needs and expectations of the community and its

youth remains crucial for ensuring that the tradition and its teachings

continue to be passed on from generation to generation in the West. Thus,

the initial focus of the study was to gather and analyze the needs of the

Ismaili community as depicted in the figure below (Figure 1).

Figure 1

E-learning

system framework and the ginans.

The Ismaili Community of the Indian Subcontinent

As mentioned

earlier, the present-day Nizari Ismaili community

members were historically referred to as the Khojas in the pre-colonial

Indian subcontinent. The religious path of the Khojas was known as Satpanth (True Path) which subscribed to the single

spiritual reality of humans irrespective of specific religion, race, or

practice. The ginans were venerated as spiritual teachings by the followers of Satpanth, the authorship of

which is attributed to several preacher-saints who are known as pirs and

sayyids in the community. The ginans were composed using a mixed

language that borrowed vocabulary primarily from Indo-Aryan languages,

including Gujarati, Hindi, Sanskrit, among others (Shackle & Moir, 2000).

The use of a mixed language enabled the composers to draw from the “bewildering

thicket of Indian religions, mythologies and intellectual traditions… The

ginans thus became and remained, until the contemporary project to

reconceptualize and reformulate the Ismaili Tariqah

(Tradition), the de facto supreme scripture for Satpanth

Ismailis.” (Alibhai, 2020, n.p.). The historical

practice of composing ginans came to an end in the mid-nineteenth century and

no new ginans have been composed since then (Asani,

2011).

The subsequent

colonization of India forced the Satpanth followers

to choose between the two dominant religious persuasions – Hinduism and Islam.

As a result, the community’s identity evolved from Satpanthi

Khojas to Ismaili Muslims. The end of the colonial rule in 1947 resulted in the

partition of the Indian subcontinent into two independent countries, India and

Pakistan. While the tradition of ginans is the heritage of the Satpanthi Ismailis, it continues to be cherished around the

world, albeit as one of many of the community’s diverse devotional religio-cultural traditions, including qasida, munqabat, munajat,

and geet. In the context of this study, the

term community is used to refer to those members of the Nizari Ismaili community in the diaspora who continue to

recognize and revere ginans as part of their religio-cultural

heritage.

The Origin and Evolution of the Corpus of Ginans

The initial

efforts to formalize and preserve the ginan corpus can be traced back to

various Ismaili individuals and entrepreneurs in the late 19th

century. For instance, Lalji Devraj (1842-1930) of India is credited to have

published the initial canon of authorized texts of ginans

in Khojki (Asani, 2011). A

few specimens of these historic publications from India have been catalogued

and preserved at Harvard Library (Asani, 1992). In

the first quarter of the twentieth century, the responsibility to publish

ginans was taken over by community institutions – starting in 1922 with the

Recreation Club Institute in India and followed by the Ismaili Tariqah and Religious Education Board

(ITREB) – a network of community-led national and regional committees across

the globe. The ITREB remained responsible for publishing religious materials

available to the community members, including the ginans.

In 1977, the Institute of Ismaili Studies (IIS) was established for the

community by the Aga Khan to promote historical and contemporary study of

Muslim cultures and their relationship with other societies and faiths. Over

time, the mandate of developing curriculum and instruction for religious

education was gradually assumed by the IIS. As Karim (2022) points out, an

unfortunate consequence of this transition has been the lack of ginan

publications:

[The IIS] has produced over a hundred books,

including five volumes on the primary materials in its collection relating to

the Arab and Persian aspects of the movement. The institute has received

hundreds of Satpanth-related manuscripts from

communal and family collections since the late 1970s; however, these sources

have suffered from neglect and their cataloguing was still awaiting completion

in 2021. Harvard University published its catalogue in 1992. Even though the

endowment of the IIS has been funded mainly by Khojas, it has produced only three

monographs on their tradition.

Asani (2021) also observes that while the Satpanth

Ismailis continue to revere ginans, the “Hinduistic” elements of the ginans remain problematic for

the institutions. This divergence of perspectives on the ginans

between Satpanth Ismailis and certain Ismaili

institutional circles remains a barrier in making any significant headway in

preserving the ginans through formalized teaching and transmission (Asani, 2021):

Anxieties about perceptions that other Muslims may

have of the ginans, in particular their vernacular Indic character, have been

the primary concerns to Ismaili institutions. These concerns have led to a

marked de-emphasis of the semantic dimension of the gināns in the contemporary articulation of official Ismaili

doctrine in favor of a Quranic one. Instead, there is an increased focus on the

performative aspects of the gināns, and their ritualization as a form of Ismaili

“devotional literature,” thus reframing them within the context of Ismaili

literary traditions in Arabic and Persian (p. 50).

This methodical reformulation of the ginans

from “Satpanthi scripture” to “devotional literature”

by the community institutions led to grave concern and anxiety about the future of ginans, particularly

among the Khoja Ismailis. Consequently, local community preachers

and missionaries (referred to as Al-waez in

the community) took it upon themselves to preserve and propagate the scriptural

status of the ginans. The efforts of Kamaluddin Ali

Muhammad and his wife Zarina Kamaluddin, notes Virani

(2015), have made ginans more accessible and comprehensible to those not

familiar with Gujarati and Khojki scripts:

Al-Waʿiẓ

Kamaluddin Ali Muhammad and al-Waʿiẓa Zarina Kamaluddin have made Herculean efforts to study and

translate this literature. Their work has added tremendously to our knowledge

of not only the Ginans, but of medieval South Asian verse in general, for the Ginanic symbols and vocabulary draw on the rich universe of

mystical meaning that had become the common inheritance of Sufis, yogis,

sadhus, bhaktas and sants. All students of this field

and lovers of the Ginans are indebted to their endeavours (p. viii).

In 2020, the IIS established the South Asian Studies (SAS) unit with

the mandate to

“contribute to current academic debates as they relate to Islam and Muslims in

South Asia and to further scholarly understanding of Satpanth

history, literature, heritage and identity to promote critical thinking in the

field of South Asian Ismaili Studies” (The Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2018).

While this broad mandate falls short of

mentioning the ginans, it is hoped that a primary responsibility of this unit

will be the development and dissemination of ginan materials to meet the needs

of community members, in particular the English-speaking community members now

living in the Western diaspora.

Aims

The

purpose of the online survey was to gather and analyze the needs and

expectations of the community members who wish to learn and understand the

ginans, and to pass on the tradition and its teachings from generation to

generation. This survey was guided by the following research

question: What are the needs and expectations of motivated English-speaking

Ismaili community learners to engage with the ginans in the Western diaspora?

The use of information technology in learning and engaging with the ginans was

assumed to be an important consideration for the English-speaking learners born

and raised in the West.

Methods

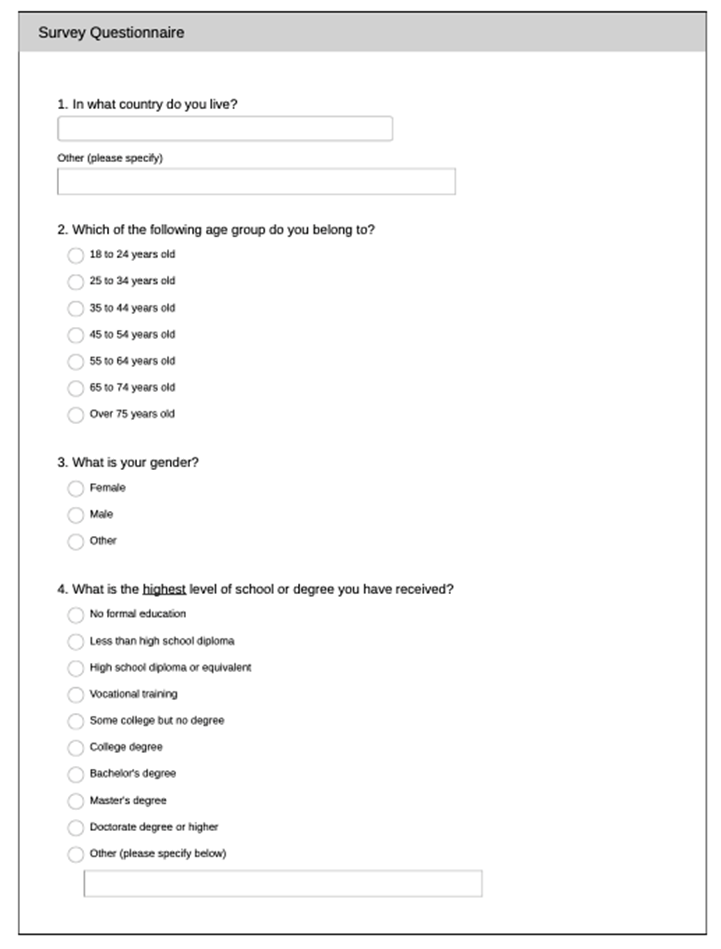

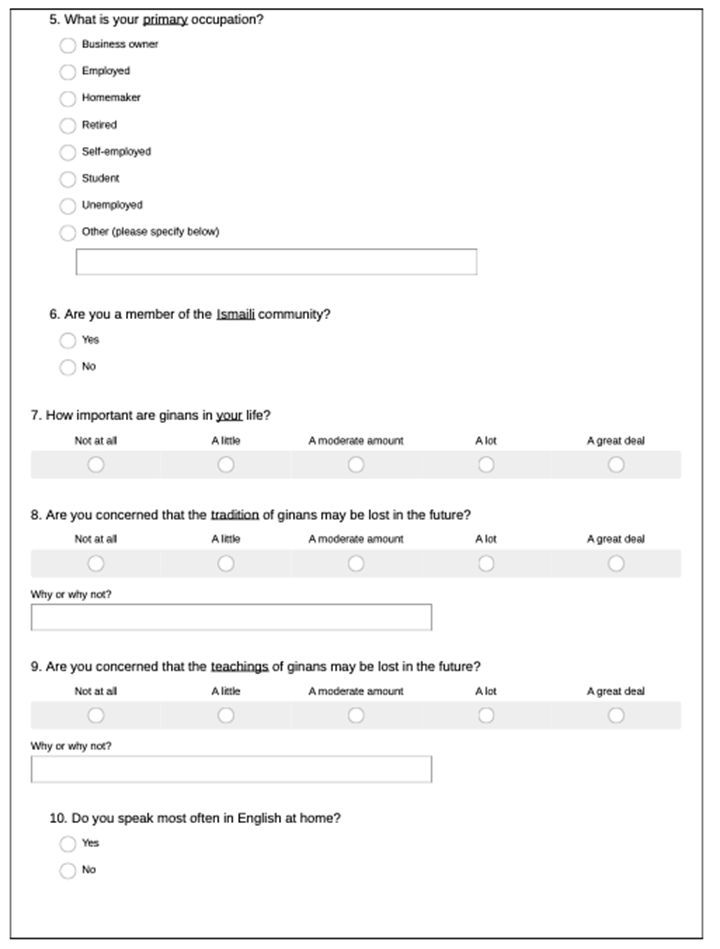

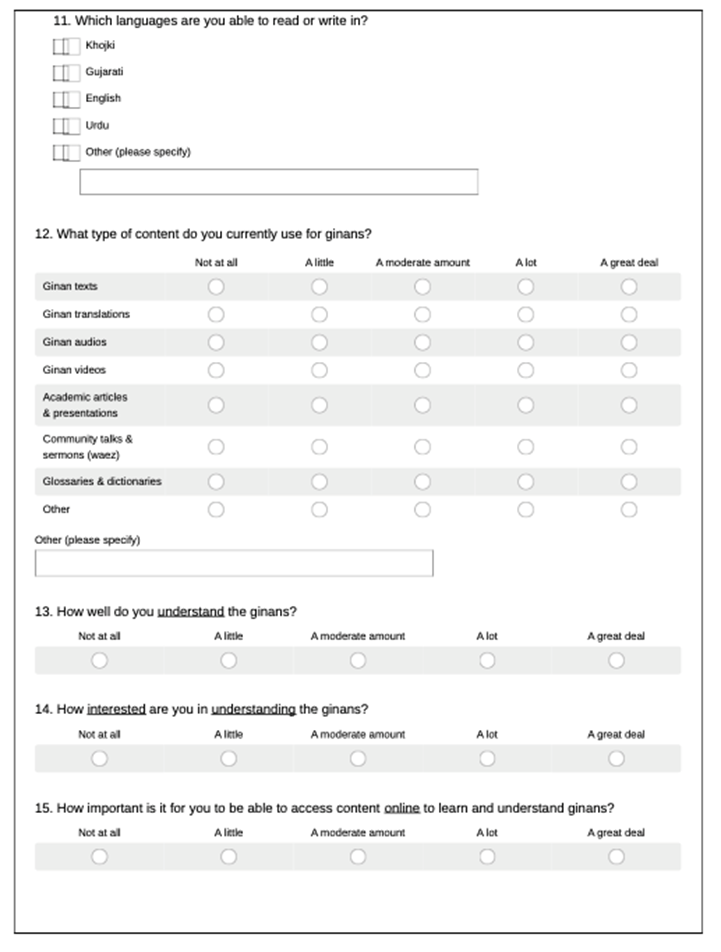

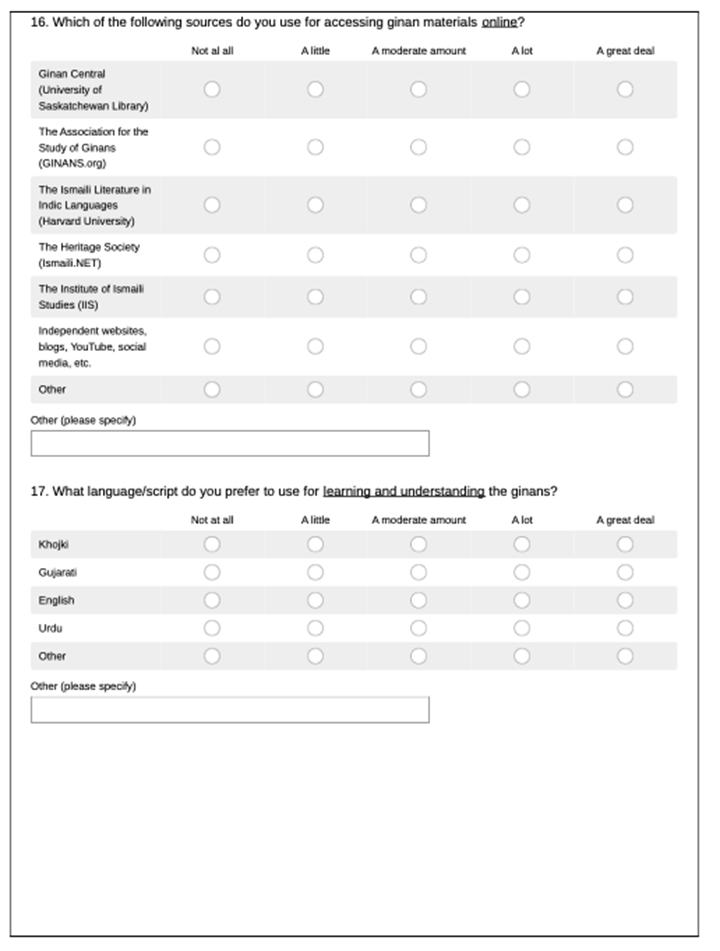

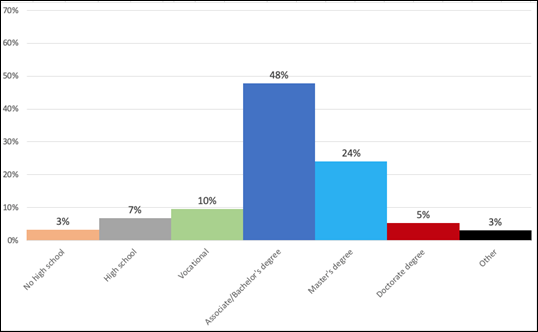

An online survey

was developed as part of this study to solicit the needs of the global Ismaili

community. The survey questionnaire contained a total of 20 questions, none of

which were mandatory and allowed participants to skip over any of the

questions. The survey questionnaire is available as an appendix (Appendix A).

The online survey was administered independently of any Ismaili community

institutions. This independence also necessitated recruiting community

participants for the survey directly using a variety of communications channels

popular in the community, including Ginan Central at the University of

Saskatchewan, Ismaili.Net Heritage, JollyGul, and GinanGuru.

Results

The online survey was administered between July 9,

2020, and September 10, 2020. It attracted 515 participants from over 20

countries around the world. Given that the global population of the Ismaili

community is estimated to be approximately 12 to 15 million, the results of

this survey are not generalizable to the entire global Ismaili community (The

Ismaili, 2022). As noted in the table below (Table 1), most of the respondents

living in the West were from Canada (46%), the United States of America (23%),

and the United Kingdom (4%). Respondents from Pakistan (8%) and India (5%) were

the leading participants from South Asia. Overall, around 85% of the survey

participants were from the diaspora and 15% were from the South Asian

countries.

Table 1

Survey

Respondents by Country

|

Country |

No. of Respondents |

Percentage |

|

Canada |

237 |

46% |

|

United States of America |

116 |

23% |

|

Pakistan |

43 |

8% |

|

India |

26 |

5% |

|

United Kingdom |

21 |

4% |

|

Other |

72 |

14 % |

|

Total |

515 |

100% |

Demographic Statistics

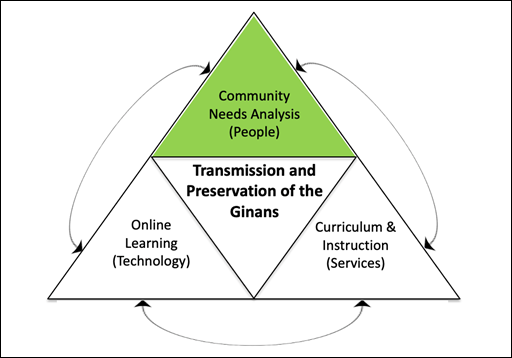

The age distribution of the respondents was grouped

into seven intervals between 18 years and those over 75 years of age. With a

98% of response rate for the question on age, the highest number of respondents

of the survey (24%) were in the age group of 55 to 64 years old (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Survey respondents by age groups.

The question on gender was answered by 505

respondents, of whom 290 identified as female (57%), 213 as male (42%), and two

as neither male nor female (0.4%). The lead by female respondents was

consistent across all age groups except in the group aged 75 years and over,

which was predominantly male at 70% (see Table 2).

Table 2

Survey

Respondents by Gender

|

Age Groups |

Female |

Male |

Other |

Total |

|

18 to 24 years old |

52% |

45% |

2% |

100% |

|

25 to 34 years old |

52% |

48% |

0% |

100% |

|

35 to 44 years old |

58% |

42% |

0% |

100% |

|

45 to 54 years old |

64% |

35% |

1% |

100% |

|

55 to 64 years old |

65% |

35% |

0% |

100% |

|

65 to 74 years old |

56% |

44% |

0% |

100% |

|

Over 75 years old |

30% |

70% |

0% |

100% |

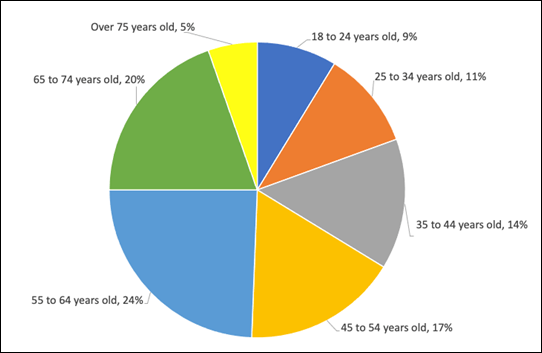

In terms of educational attainment, over 75% of the

respondents claimed to have at least one degree and only 3% of the respondents

had not completed a high school degree (see Figure 3). Further analysis of this

data revealed that 89% of the respondents from South Asia had at least one

degree as opposed to 75% of respondents in the diaspora with at least one

degree.

Figure 3

Survey respondents by highest level of education.

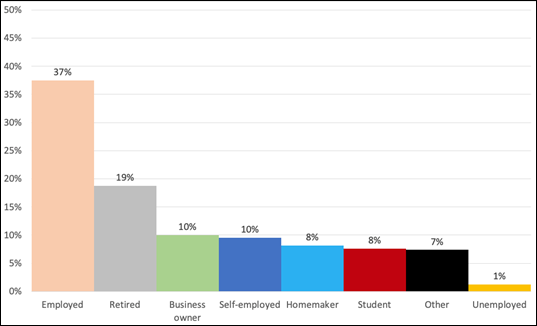

Around 37% of the survey respondents identified

themselves as employed professionals. In addition, 20% of the respondents

identified as either business owners or self-employed. Over one-quarter of the

respondents (27%) identified as either retired or homemakers. A visual summary

of the primary occupation of the survey respondents is presented in the chart

below (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Survey respondents by primary occupation.

Target Population Profile

As evident from the demography analysis, there was a

wide range of diversity in terms of geography, age, gender, education, and

occupation among the respondents. Owing to this geographic and demographic

spread of the survey participants, the survey respondents were divided into two

groups. The survey target group consisted of respondents who

belonged to the target population defined for this study – English-speaking

Ismaili community members aged between 18 and 44 years who currently reside in

Euro-American countries. In contrast, the general group comprised the

respondents who fell outside the target population. The target group

respondents were identified by combining the responses of four specific

questions in the survey (Q1 – Country of residence, Q2 – Age group, Q6 –

Community membership, and Q10 – Primary language).

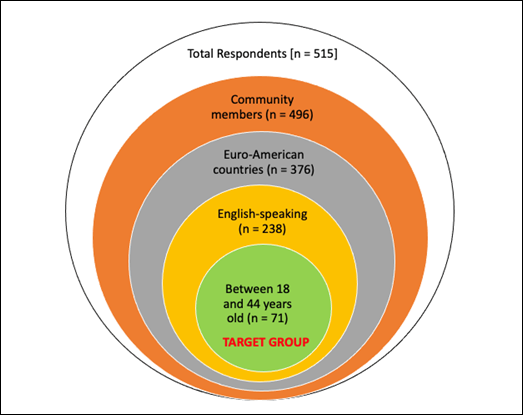

As depicted in the chart below (Figure 5), of the

515 total survey respondents, 496 respondents identified themselves as members

of the Ismaili community. A total of 376 of these respondents lived in

Euro-American countries, and 238 of them designated English as their primary

language. Finally, the pool of respondents in the target group was reduced to

71 when the age requirement was considered. Thus, the final size of the survey

target was determined to be 71 or around 14% of the total number of respondents

(n = 515).

Figure 5

Identifying respondents in the survey target group.

Gathering Needs and Expectations

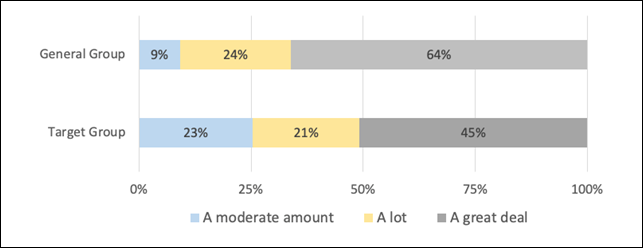

It was helpful to benchmark the target group in

relation to the other respondents in the general group to analyze the needs

assessment survey data. Doing so helped provide a consistent baseline in

identifying and comparing, as well as contextualizing, unique needs and

attitudes between the two groups. For instance, when analyzing the data for the

question on the importance of ginans in their lives (Q7), the expected

difference in the attitudes between the two groups could now be visualized. A

lower percentage of the target group (89%) attached moderate to high importance

to ginans than the general group (97%), as depicted in the figure below (Figure

6). The evidence also validates the fundamental premise of this study that

ginans must be made relevant to the younger generations based on their current

socio-economic contexts.

A strong agreement between the needs of the two

groups was observed with regards to having access to ginan resources. An

overwhelming majority (97%) in both groups attached moderate to high importance

to having online access to ginan resources. On the question of preferred

devices to access online ginan resources as well, there was notable synergy in

the needs of the two groups. The use of mobile phones remained the most

preferred device in the target group for 97% of the respondents in comparison

to 91% for the general group. The two groups diverge in their preferences,

however, when it comes to accessing ginan resources in the form of books, CDs,

cassettes, etc. More than one-quarter (28%) of the respondents in the general

group attach moderate to high importance to analog resources in comparison to

less than one-tenth of the respondents in the target group.

Figure 6

Importance of ginan in target and general respondents groups.

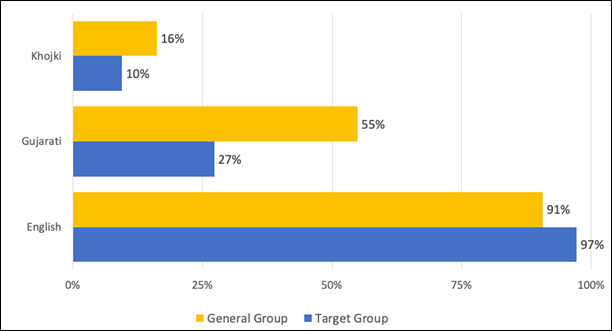

Given the demography of the target group, it was

expected to find an overwhelming demand (97%) for the Latin script and English

as the language of instruction for the ginans. It was surprising, however, to

find the English language to be preferred by 91% of the respondents in the

general group. While none of the other scripts come close to the strong support

shown for English, Khojki and Gujarati remain alive

and important in the community even today (Figure 7). The findings of the

survey reflect the historical decline of Khojki and

Gujarati scripts in favour of English as a substantial number of the community

members have moved away from the Indian subcontinent to the West.

Figure 7

Language preference for learning and understanding

ginans.

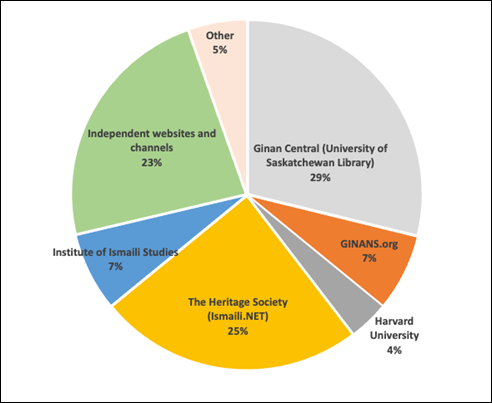

Most of the respondents in both groups (89%)

considered online access to ginan materials to be important. Due to the lack of useful ginan content on the official community

institutional websites, community

members use various external websites to access ginan materials

(Figure 8). Thus, there is a deep

desire in the community to use online ginan websites and content that are

either produced or endorsed by community institutions. As one community

participant stated, the need for developing “a unified website which is

accredited by IIS that is made available globally and it should have authentic

text and raags of ginans” (Respondent #506).

Figure 8

Most preferred websites for accessing ginan materials.

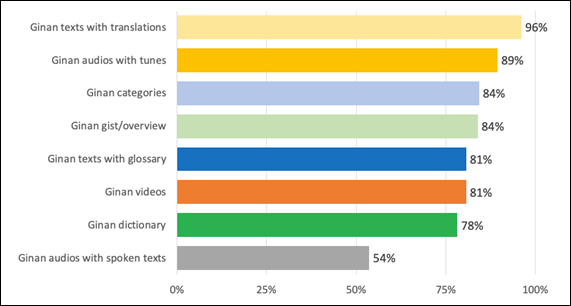

To ascertain the types of online materials desired

by ginan learners, a variety of options were presented to the respondents to

rank as part of the needs assessment survey. These options were ranked

independent of each other by the respondents. Having access to ginan texts and

translations in English was ranked as the most desirable resource for learning

and understanding of the ginans (Figure 9). This outcome is not surprising as

it is a common practice to use ginan text and translation side-by-side during

in-person instructional sessions.

Figure 9

Useful resources for learning and understanding

ginans.

The second most desired

content type was audio recitations of ginans. In an in-person instructional

setting, the instructor is responsible for reciting ginans to the learners. In

an online and self-learning setting, where there are no instructors, the

availability of digital audio is crucial. The need for information on ginan

categories was also ranked as desirable by 84% of the respondents. The ginan

categories are used to group ginans based on various ceremonial and topical

themes. In recent years, the knowledge of ginan categories has been confined to

the community elders and experts who typically impart this knowledge to

learners during their in-person instructional sessions.

Another sought-after resource

for learning and understanding ginans that was ranked considerably higher in

the needs assessment survey was the summary of individual ginans, commonly

referred to as ginan “gist” in the community. Over the past decade, it has

become a common practice for reciters to read out the gist of the ginan in

English that they are called upon to recite during congregational services held

for special occasions. The gist texts explain the message and sentiments of

ginans in broad strokes for the English-speaking members of the congregation

who often struggle to understand what is being recited. Despite this being a

common practice, the community institutions have yet to produce any publication

with ginan gists that can

be readily accessed by the community.

Ginan dictionary and

multimedia ginan videos were ranked equally high in the survey. When analyzed

based on specific groups, only 67% of the respondents in the target group

attach moderate to high importance to a ginan dictionary as opposed to 80% of

those outside the target group. The need for multimedia videos is also

relatively less pronounced in the target group at 77% as opposed to 81% in the

general group.

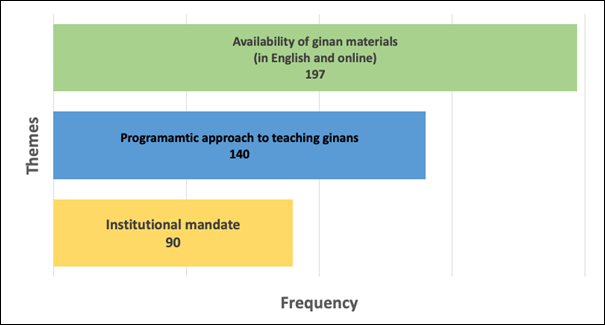

Figure 10

Thematic summary of the needs and expectations of

the survey respondents.

The qualitative analysis of the only open-ended

question in the survey (question # 20) revealed three distinct themes (Figure

10). Overall, the survey found that the availability of ginan resources in

English remains a crucial need for the target group members who have little or

no knowledge of the language of the ginans. The development and dissemination

of curriculum-based educational programs and supporting materials for the

ginans emerged as the most urgent and unmet expectations. The sentiment for a

more pronounced acknowledgement of the heritage of ginans and its significance

in the communal and scholarly undertakings of its institutions and leaders was

found to be equally prevalent amongst the target and general group respondents.

Discussion

Based on the analysis

of the survey data, an aggregate profile of the needs and expectations of the

target group – English-speaking Ismaili community members aged between 18 and

44 years who currently reside in the West – can be depicted as follows. A typical target group member is an

educated citizen of an English-speaking country such as Canada. They consider

ginans to be an important part of their life even though the language of ginans

remains mostly foreign to them. They value the emotive and performative aspects

of the tradition that help them express their devotion and solidarity to the

Ismaili faith and community. They remain very concerned that the ginans, and

more so the teachings that the tradition encapsulates, will be lost if nothing

is done about it by the community and its institutions.

The

survey results provide tangible evidence of the need to utilize information

technology for making ginans accessible. The survey revealed that close to 90%

of the survey respondents preferred having access to ginan materials online,

which challenges the taboo of incorporating contemporary information

technology to complement traditional ways of accessing and teaching the ginans.

From a learner-centric perspective, the use of information technology is imperative

for engaging learners to embrace traditional languages and traditions.

There is little

doubt that the present-day ginan corpus has survived over the past centuries

primarily due to the foresight and adaptability of the Ismaili community to embrace

print technology to preserve the ginan texts. Now it is time for the community

to once again summon its spirit of adaptability and courage to embrace

information technology to ensure the continuity of the ginans in the digital

age. The future survival of the tradition of the ginans in the West remains

highly dependent on the continued engagement of the community youth through

information technology.

With its

deliberate focus on the people dimension of the e-learning framework to

gather community needs, this research opens pathways to expand on the technology

and process dimensions of the e-learning system framework in charting

the future of the ginans by the Ismaili community and its institutions. The

community institutions are well-positioned to address some of the fundamental

issues to ensure continued transmission and preservation of the ginans in the

Western diaspora.

Standardized Romanization

The phonetic

demands of the oral and mixed nature of the ginan language posed challenges for

the limited phonetic strength of the Khojki script

initially used to transcribe the ginans (Virani, 2017).

Unfortunately, these shortcomings were never addressed systematically and were

passed on as the ginan corpus was canonized from Khojki

to a more established Gujarati script. The canonized ginan

corpus in Khojki and Gujarati were then used as the

basis for the romanization of ginans into the Latin or English writing system. As a result, variant ginan romanization conventions started to emerge

from different countries where the community resided. For instance,

the palatal or hard “d” sound as in the word doctor, is

found to be romanized with variants such as the use of successive d (dd),

capitalization (D), italicization (d),

and with a dot below (ḍ). Community

institutions such as the national ITREBs and the IIS are

well-placed to standardize romanization conventions for the transliteration of

the ginans.

Having a

standardized romanization convention will not only make the ginan corpus more

reader-friendly but will allow ginan texts to be computationally analyzed using

natural language processing for various purposes, including creation of lexical

resources. As Bowker (2018) explains, availability of credible and

representative corpus remains at the heart of enhancing human understanding

through computational analysis in language learning:

Consider that a corpus is a text file. It could be made up of tens,

hundreds, or thousands of documents and may run to hundreds of thousands or

even millions of words. Trying to count the number of words, or the number of

times each word occurs, would be a time-consuming, labor-intensive and

error-prone process if it were done manually. However, this type of work is

easily accomplished by a computer, and corpus analysis software can be used to

calculate several different measures of frequency, including raw frequency

counts (e.g., word lists), measures of disproportionate frequency (e.g., keyness), and measures of relative frequency (e.g.,

collocations) (p. 361).

Ginan Dictionary

Another potential measure that the community institutions can take is

to commission an English dictionary of the ginans. While several ginan

resources feature back-of-the-book ginan glossaries with English meanings, an

English dictionary of the ginans is yet to be developed and published. If

ginans are to be understood by English-speaking youth of the community, the

availability of a ginan dictionary must become a priority for community elders

and leaders. Given the high preference in the community for online access, it

may be worthwhile to make such a dictionary available online.

When it comes to forgotten and endangered languages, a dictionary

becomes a tool for language preservation (Gippert et

al., 2006). With the language of the ginans being oral, mixed,

and endangered simultaneously, it must be preserved not just for the community

but also for scholarly research. Thus, a comprehensive ginan dictionary will

make it possible to study rare and complex forms of linguistic expressions manifested

in the vocabulary of the ginans.

Ginan Curriculum

There appears to be a deep desire in the community for its institutions

to embrace a programmatic approach for the development and administration of

curriculum-based in-person and online ginan classes. The expectation here is

that the curriculum for these classes will not only teach the meanings and

tunes but will ensure that the history and teachings of ginans are also made

relevant to the community’s contemporary context as a diaspora community. At a

deeper level, this need of the community

youth is indicative of their desire to find comparable and compatible

expressions of their faith and devotion in English-speaking societies. From

this perspective, “translation” is no longer an exercise in finding linguistic

equivalence but, as Stewart (2006) notes, a quest to seek equivalence of one’s

faith in the local culture (p. 286-87):

[T]he search for

equivalence in the encounter of religions—when understood through the

translation models we have characterized as literal, refractive, dynamic, and

metaphoric—is an attempt to be understood, to make oneself understood in a

language not always one’s own; it does not necessarily reflect religious

capitulation or theological ignorance or serve as the sign of a weak religious

identity…. The texts that reveal actors attempting to locate commensurate

analogues within the language tradition capture a unique ‘moment’ in the

process of cultural and religious encounter, as each tradition explores the

other and tries to make itself understood (p. 286-7).

The ginans, like

many other ethnocultural traditions and knowledge, remain under-studied as an

academic area of research in Western academia. From a

broader perspective, the results of this study have wider relevance to other

diasporic ethnocultural communities that may be facing similar challenges in

imparting and safeguarding their traditions and knowledge.

Conclusion

This article presented a brief historical overview of how the Ismaili community members have managed to

safeguard the ginans despite the geopolitical upheavals that the community has

been subjected to as a political, ethnic, and religious minority community. It

also unveiled the present divergent perspectives on

the ginans between the community members of Khoja descent and the

community institutions which continue to exacerbate the anxiety about the

future of ginans. Finally, the responses of the global

online survey were analyzed to identify the needs and expectations of the

community to chart the future of the ginans in the Western diaspora. The survey

found that the availability of online ginan materials and resources are highly

desirable by the English-speaking community members who want to learn and

understand the teachings of the ginans. In addition, the survey also uncovered

the community’s strong expectation to see the ginans become a priority in

educational and scholarly programming and publishing initiatives of the

community institutions.

Acknowledgement

This article is an abridged version of the author’s

unpublished doctoral dissertation, titled Tradition and Technology: A

Design-Based Prototype of an Online Ginan Semantization Tool, which was supervised by

Professor Jay Wilson at the University of Saskatchewan.

References

Alibhai,

M. (2020, March 5). Tajbibi Abualy

Aziz (1926-2019) Part one: A Satpanthi Sita. https://theolduvaireview.com/tajbibi-abualy-aziz/

Aparicio,

M., Bacao, F., & Oliveira, T. (2016). An

e-learning theoretical framework. Journal of Educational Technology

& Society, 19(1), 292-307. https://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.19.1.292

Asani, A. S.

(1992). The Harvard collection of Ismaili literature in Indic

languages: A descriptive catalog and finding aid. Boston: G.K. Hall. https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:13785163$1i

Asani, A. S.

(2002). Ecstasy and enlightenment: The Ismaili devotional literature of

South Asia. London: I.B. Tauris. https://www.iis.ac.uk/publication/ecstasy-and-enlightenment-ismaili-devotional-literature-south-asia

Asani, A.

S. (2011). From Satpanthi to Ismaili Muslim: The

articulation of Ismaili Khoja identity in South Asia. In F. Daftary (Ed.), A modern history of the

Ismailis: Continuity and change in a Muslim community (pp. 95-128).

London: I. B. Tauris Publishers. https://words.usask.ca/ginans/files/2020/05/2011-Asani-Khoja-Identiity-in-Modern-History-of-Ismailis.pdf

Asani, A.

S. (2020, December 20). Towards a religiohistory

of Ginans [Webinar]. The Association for the

Study of Ginans. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=23KHQGiED24

Bowker,

L. (2018). Corpus linguistics is not just for linguists: Considering the

potential of computer-based corpus methods for library and information science

research. Library Hi Tech, 36(2), 358-371. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHT-12-2017-0271

Gippert, J., Himmelmann, N., & Mosel, U. (Eds.). (2006). Essentials

of language documentation. Berlín: Mouton de

Gruyter. https://genderi.org/pars_docs/refs/58/57633/57633.pdf

Ivanow, W. A.

(1948). Collectanea (Volume 1). Leiden, Holland: E. J. Brill. http://www.ismaili.net/Source/0723.html

Karim,

K. H. (2022). Khoja Isma’ilis in Canada and

the United States. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.841

Kassam,

T. R. (1995). Songs of wisdom and circles of dance: hymns of the Satpanth Isma'ili Muslim saint, Pir Shams. SUNY Press. https://sunypress.edu/content/download/449846/5466323/version/1/file/9780791425916_imported2_excerpt.pdf

Shackle,

C., & Moir, Z. (2000). Ismaili hymns from South Asia: An

introduction to the Ginans. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon Press. https://books.google.ca/books?id=y8lO79JtYjUC

Stewart,

T. K. (2001). In search of equivalence: Conceiving Muslim-Hindu encounter

through translation theory. History of Religions, 40(3),

260-287. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3176699

Tennant,

R. (2004). A bibliographic metadata infrastructure for the twenty‐first

century. Library Hi Tech, Vol. 22 No. 2, pp. 175-181. https://doi.org/10.1108/07378830410524602

The

Institute of Ismaili Studies. (2018). South Asian Studies. https://www.iis.ac.uk/content/south-asian-studies

The

Ismaili. (2022). The Ismaili Community. https://the.ismaili/global/about-us/the-ismaili-community

Virani,

S. (2015). Introduction. In Ginans with English translation and glossary –

Volume 9 (pp. viii-xvi). Pakistan. https://www.academia.edu/37220475/Introduction_Ginans_with_English_Translation_and_Glossary_Volume_9

Virani, S. (2017, October). Garlands of sounds

(Varṇamālā): Establishing

a phonology of the Khojki script. Paper presented

at Before the printed word: Texts, scribes and transmission - A symposium on

manuscripts collections housed at the Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, UK.

https://www.iis.ac.uk/events/printed-word-texts-scribes-and-transmission

Appendix A

Online Survey

Questionnaire