Research Article

Doing More with a DM: A Survey on

Library Social Media Engagement

Jason Wardell

Health & Life Sciences

Librarian

University Libraries

University of Dayton

Dayton, Ohio, United States

of America

Email: jwardell1@udayton.edu

Katy Kelly

Coordinator of Marketing and

Engagement

University Libraries

University of Dayton

Dayton, Ohio, United States

of America

Email: kkelly2@udayton.edu

Received: 4 Apr. 2022 Accepted: 20 July 2022

![]() 2022 Wardell and Kelly. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2022 Wardell and Kelly. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30141

Abstract

Objectives

– This study sought to determine the role social

media plays in shaping library services and spaces, and how queries are

received, responded to, and tracked differently by different types of

libraries.

Methods

– In April and May of 2021, researchers conducted a

nine-question survey (Appendix A) targeted to social media managers across

various types of libraries in the United States, soliciting a mix of

quantitative and qualitative results on prevalence of social media

interactions, perceived changes to services and spaces as a result of those

interactions, and how social media messaging fits within the library’s question

reporting or tracking workflow. The researchers then extracted a set of

thematic codes from the qualitative data to perform further statistical

analysis.

Results

– The survey received 805 responses in total, with

response rates varying from question to question. Of these, 362reported

receiving a question or suggestion via social media at least once per month,

with 247 reporting a frequency of less than once per month. Respondents

expressed a wide range of changes to their library services or spaces as a

result, including themes of clarification, marketing, reach, restriction,

collections, access, service, policy, and collaboration. Responses were

garnered from all types of libraries, with public and academic libraries

representing the majority.

Conclusion – While there remains a disparity in how different types of libraries

utilize social media for soliciting questions and suggestions on library

services and spaces, those libraries that participate in the social media

conversation are using it as a resource to learn more from their patrons and

communities and ultimately are better situated to serve their population.

Introduction

Social media use

by libraries as institutions is a well-established research topic. Existing

published research tends to focus on content strategies at a practical level,

such as case studies and how-tos. In contrast, this

study intends to fill a gap within the literature about current practices of

social media management and the direct engagement happening between libraries

and the communities they serve. The literature review will focus on social

media and libraries in terms of the current landscape, user engagement, and

managers’ perspectives.

Literature Review

Current Landscape

As a free

communication tool, social media increases the capacity for companies,

institutions and groups to promote themselves, view what people are saying

about them, and converse with customers. According to Edison Research (2021),

82% of the total U.S. population over the age of 12 use social media, an

increase from 79% in 2019 and 80% in 2020 (p. 20). The Pew Research Center

(2021, April 7) reports usage as around 72% and that Facebook and YouTube are

the most used platforms, also stating that those companies’ “user base is

broadly representative of the population as a whole.” Institutions can use

social media surveys like these to inform their strategy, depending on their

intended audience and the content they produce.

Accordingly,

libraries in the U.S. that manage social media accounts use Facebook more than

any other social platform while “Twitter is the next most popular platform,

used by 67% of libraries, followed by Instagram, used by 56% of libraries”

(OCLC WebJunction, 2018, February 13). These

platforms provide opportunities to share content widely and communicate

one-on-one with people. Most libraries use their social media to share upcoming

events and event photos, while some choose to engage directly with their

communities by offering reader’s advisory or research help (OCLC WebJunction, 2018, February 13). The American Library

Association (ALA, 2018) approved a set of social media guidelines for

libraries, including creating a social media policy, staffing and managing the

platforms, and making strategic decisions about intended audience and one-way

or two-way communication. The guidelines conclude with the potential positive

outcomes of libraries using social media, such as presenting the opportunity

for “libraries to engage with users and to make significant contributions to

shared knowledge. This robust civic engagement leads to an informed citizenry

and a healthy society, while also demonstrating the great value of our

institutions” (ALA, 2018). The ALA’s guidelines offer both encouragement and

caution, striking a balance of outlining opportunities as well as consequences

libraries could face.

User Engagement

The literature also weighs the opportunities,

positives, and negatives of using social media to engage with users as

individual institutions. Researchers conduct content analyses of social media

accounts to arrive at conclusions about trends and strategies. A study by Kushniryk and Orlov (2021) analyzes the Twitter posts and

interactions of 12 large public libraries in North America and concludes with

suggestions of how libraries have opportunities to better leverage Twitter by

engaging in dialogic communication. They suggest building better relationships

by “replying to inquiries, providing feedback, commenting, and retweeting

messages” (p. 6). Practitioners and researchers emphasize the importance of

continuously developing a communication strategy, or keeping social media

social, with practices such as such as surveying your intended audiences’

social media habits and preferences (Howard, Huber, Carter and Moore, 2018) and

moving beyond simply broadcasting messages and towards building connections and

having conversations to “develop relationships, improve real-world services and

resources, affect policy, and meet target goals (Trucks, 2019, p. 12).

Some have compared traditional services to what’s now

possible with social media. In the introduction to their study of academic

librarians’ perspectives, Ahenkorah-Marfo and Akussah (2017) write “[reference librarians] employed

face-to-face conversations with users. Of late, however, the service

environment increasingly demands digital reference service, more especially,

synchronous service” (p. 1). On the other hand, researchers express caution

concerning the negative outcomes of using social media to engage with patrons. Katopol (2017) warns that it enables greedy behavior

because a library’s social media presence needs constant attention and requires

staff to be available 24/7 through cell phone and email (p. 3). Kliewer (2018) calls attention to privacy concerns and the

problematic practices of social media companies. Social media engagement

tactics can run counter to longstanding library ethics and principles.

Managers’ Perspectives

Some research, including this study, seeks out social

media managers in libraries to ask about their practices and perspectives. One

of the earliest surveys was presented by Rogers (2009, May 22) and reveals

library use of blogs, social networking, and instant messaging to market and

promote library services. The excitement and potential for reaching more people

and meeting them online, where they were increasingly spending time, is a major

theme of survey respondents (p. 6). Another theme is respondents’ perceiving

the lack of staff time as a major barrier to participating in these tools

(pp.6-7). In 2014, Taylor & Francis Group published a white paper about

libraries’ practices and future opportunities with social media. Their survey

results show that promoting events, services, and resources were all top

priorities, followed by more engagement-centered objectives such as connecting

with new students, engaging with the academic and local community, and as a

customer service tool (p. 8). Social media tracking and assessment varied, some

citing the fact that they don’t have a significant number of users to warrant

writing a report, like other libraries choose to do (p. 21).

Other manager-specific perspectives are discussed in a

study that surveyed art librarians; 71% agreed or strongly agreed that social

media can increase visitors and collection use in their library (Sulkow et al., 2019, pp. 308-309) and in their case study,

a manager cites that “content creation, regular engagement, image editing, and

other time-consuming activities are forms of labor that are often hidden from

coworkers and administration” (p. 315). Unlike the study presented below, these

do not focus on direct messaging or engagement with social media users. The

themes in this literature review, such as staff time, reporting, and providing

services, are relevant to the survey results.

Aims

This study’s aim was to determine the role social

media messaging plays in shaping library services and spaces across all types

of libraries. The authors sought to explore how and how often libraries of

different types directly engage with their patrons on social media and how

queries are managed.

Methods

To better

understand the current use of social media by libraries to solicit and respond

to questions and feedback, the researchers wrote an online survey intended for

managers of social media within all types of libraries in the United States.

For this research, “managers of social media” was defined as any individual who

is responsible for monitoring or posting on social media on a library’s behalf.

All library social media managers were encouraged to respond; there was no

limit per library.

Following IRB

approval, the 9-question online survey (see appendix A) launched in April 2021.

Each question was optional. Between April 28 and May 14, the researchers and

their colleagues shared the invitation to participate, focusing the project’s

initial communication on Ohio library workers through Ohio-specific electronic

mailing lists. Between May 18 and June 4, the invitation was shared to a

national audience by the researchers and their colleagues using the American

Library Association’s discussion boards, library marketing-specific Facebook

groups, and various professional association electronic mailing lists. The

survey was intentionally distributed to professional organizations for multiple

types of libraries to ensure data collection and representation from public,

academic, school, government, and special libraries. Appendix B includes a

timeline of the invitation sharing to each communication channel and their

approximate reach.

Between April 28

and June 4, 2021, 805 people responded to the survey. The researchers

independently analyzed and coded responses to the survey’s two open-ended

questions using Qualtrics XM software for qualitative and quantitative

analysis, identifying 12 themes within Q7 responses and 6 in Q8 after comparing

findings and reconciling discrepancies.

Results

Survey results revealed experiences and practices of

social media managers in libraries. The first two questions filtered out

respondents who were ineligible to participate. All 100% affirmed they were

willing to take the survey. Of these, 23 respondents said they were not social

media managers in response to question 3 and the survey ended for them. The

remaining 763 participants, self-identified social media managers, continued

the survey. Since the individual questions were optional, the total number of

responses varied from question to question.

The subsequent questions inquired about the person’s

own engagement experiences while using their library’s social media account(s).

Of those who answered question 4 (n=615), nearly 92% reported receiving

questions or suggestions; 8% have not. For the respondents of question 5

(n=614), nearly 97% reported that they respond to questions or suggestions.

There were 29 people who answered Q5 affirmatively, but either skipped or said

no to Q4.

The next section of the survey asked participants to

report the frequency of engagement and practices related to questions or

suggestions received on social media. It includes the survey’s two open-ended

questions that the researchers coded and analyzed.

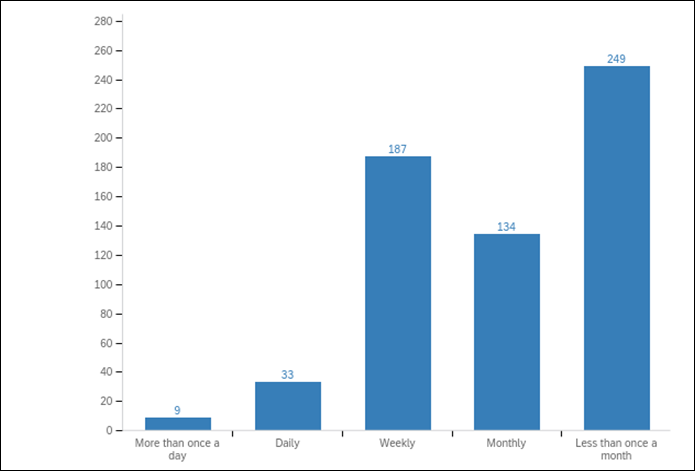

Most commonly, respondents reported receiving

questions or suggestions less than once a month (n=249). The next highest

number of respondents (n=187) said they received questions or suggestions

weekly. The remaining options presented in the survey were monthly (n=134),

daily (n=33), and more than once a day (n=9). See Figure 1.

Figure 1

Q6:

“Approximately how often do you receive questions on your library’s social

media?”

Question 7 asked survey respondents “what has changed

in your library services or spaces as a direct result of questions or

suggestions received via social media?” The 12 themes that emerged from the

researchers’ qualitative coding process on changes to library services or

spaces are listed in the next section. Each individual response was given one

or more of these codes, describing how the library’s services or spaces changed

or didn’t change.

Description of Codes, With Representative Samples

Samples have

been abbreviated for clarity. The anonymized data set of responses is available

upon request.

Clarification (n=143): A response to a question via social media. This includes quick, ready

reference questions in addition to access-related questions. This is considered

a change to services, as it represents a new platform by which to communicate

with patrons.

●

Public library in New York: “People want to verify

services and hours of operations as well as ask questions about programs”

●

Government library in Kentucky: “[The] majority of

questions we receive are how to research, and we direct them to the appropriate

page on our website.”

●

Academic library in Pennsylvania: “[Questions] are

generally just basic ones like "Is the library open today?"”

Marketing (n=49): An

adjustment to messaging off social media. This includes changes to physical

signage, website content, or advertising. This is considered a change to

spaces, either physical or digital.

●

Academic library in Ohio: “Mostly it has been people DMing questions or letting us know about noise

complaints…We did increase signage as a result.”

●

Public library in Pennsylvania: “It helped me identify

where we can improve communication with the public such as where and what we

include on flyers and brochures”

●

Public library in Massachusetts: “We became aware of

people with autism preferring the term "Autism Acceptance," and

changed our signs and SM accordingly.”

Reach (n=103): An increase in

usage of social media on the part of the library social media manager. This

includes consciously increasing the content, maintenance, or monitoring of a

library’s social media. This is considered a change to services.

●

Government library in Mississippi: “[Social] media is

an easy way for people to contact us. It helps us to be available to all of our

patrons, not just those who can make it into the building or call us on the

phone.”

●

Public library in California: “Social media gives us a

bit of a thermometer on what people know, want to know, and don't know about

our services.”

Restriction (n=5): A

decrease in usage of social media. This includes automatic responses saying the

library does not check social media messages, messaging redirecting users to

traditional service points, or anything to dissuade users from contacting the

library over social media. This is considered a change to services.

●

Public library in Massachusetts: “We have more

explicit autoresponders on social media telling people we don't monitor in realtime [sic], and alerting them to [phone, email,] chat

options instead.”

●

Public library in Massachusetts: “[We] had an

autoresponder asking folks to email us…especially so the more detailed requests

that involve different people could have everything altogether instead of

spread out through a chat. Also because messages sent

to the page were easy to accidentally miss and often sent at odd times when no

one was online.”

Collections (n=33): An

addition to the library collection instigated by communications using social

media. This includes physical and digital purchases and subscriptions as well

as coordination for donations. This is considered a change to services.

●

Public library in Pennsylvania: “We have purchased a

couple books based off of some suggestions on social media.”

●

Public library in Pennsylvania: “Sometimes patrons'

messages help us with collection development, as they message us through

Facebook to ask us if a certain title is available or if we can purchase a

certain title.”

Access (n=33): A change to

the ways in which a patron might interact with the physical library space. This

includes changes to hours, reconfiguration of seating, improved WiFi. This is considered a change to services or spaces.

●

Public library in New York: “It's hard to measure

exactly, but we speeded up our timeline for reopening our doors to the public

because of "suggestions" -- more like annoyed comments! -- from

patrons.”

Service (n=76): A change to or

addition of patron-facing programming. This includes in-person events, online

versions of previously offered services, or the creation of new platforms for

patron interaction. This is considered a change to services.

●

Academic library in California: “We notice trends,

when there is a preponderance of questions, it means that [we] have to address

the topic, either on our social media or with addressing changes itself on our

library space. For example, our campus has many parents, and since we received

many questions about children in the library, we created a children's space.”

●

Public library in Pennsylvania: “We are able to handle

more online reference questions and online programs due to social media”

Policy (n=16): An internal

change to how the library—in whole or in part—responds to certain situations.

This includes policies on social media, mindfulness and continuity in

messaging, and procedures when it comes to recording social media messages as

reference transactions. This is considered a change to services.

●

Public library in Pennsylvania: “We have formed a team

of public service staff responsible for monitoring and answering questions on

social media. Previously this task was the responsibility of marketing.”

●

Public library in New York: “We had many questions

that we realized staff had different answers to. It made us rethink, rewrite,

or write new procedures that made clarifications for both staff and patrons.”

Collaboration (n=8): A new connection between

departments within the library or between the library and external partners,

either instigated by or founded on social media communication.

·

Academic library in Ohio: “Lots of partnerships with

other departments on campus. The questions are in the forms of tagging us in an

event or initiative to share with our audience. But we have had comments

questioning our intent when posting about race. We took immediate internal

action by meeting and consulting with the university social media contact.”

In addition, three “no-change” codes were identified:

Nothing (n=124): The respondent states that

there has been no change to library spaces or services as a result of social

media interaction.

·

Public library in Maine: “Not much. Because I am

technically not a member of our patrons services team,

I let people know what is being said but not much changes.”

·

Public library in Florida: “Very little. I report the

suggestions and questions but it's rare department heads or administrators

actually act on the feedback, unfortunately.”

N/A (n=19): The respondent claims that the question is not

applicable to their library, and no further clarification is given. The authors

considered this to be different from a “Nothing” response, in that it suggests

there has been no opportunity for change, whereas “Nothing” suggests the

opportunity existed, but no change was made.

Unclear (n=9): The wording of the response is ambiguous or

uninterpretable.

·

Academic library in Florida: “Unsure, information

doesn't usually reach back to me.”

A total of 618 respondents elaborated on their

experiences in response to this question. Overall, the top three themes across

all libraries were Clarification, Nothing, and Reach.

Question 8 inquired “how are these questions and

suggestions reported and/or tracked?” The six themes that emerged were:

·

Not (n=289): They are not reported or tracked.

·

Included (n=100): They are included in the library’s

overall reporting or tracking mechanism.

·

Referral (n=69): They are referred to the appropriate

person or department.

·

Separate (n=37): They are tracked separately as social

media engagement.

·

Yes, other (n=16): They are reported and tracked but

in other ways.

·

Unknown (n=2): The respondent does not know.

There were 513 responses to this question. The

majority of participants (56%) stated that questions or suggestions are not

reported and/or tracked. The other top themes showed that social media

engagements are included in overall library counts (19%) or that questions and

suggestions are referred to someone else by the social media manager (13%).

The final survey questions investigated the

demographics of respondents. Question 9 asked “what type of library do you work

for?” 612 participants answered this question; every type of library was

represented by at least one respondent. The majority represented public

libraries (61.60%) while workers in academic libraries (26.63%) represented the

second largest group of participants.

Question 10 asked respondents to report the state where

their library is located. Social media managers in Pennsylvania represented

26.6% of the respondents while libraries in Ohio and Texas had high

representation as well.

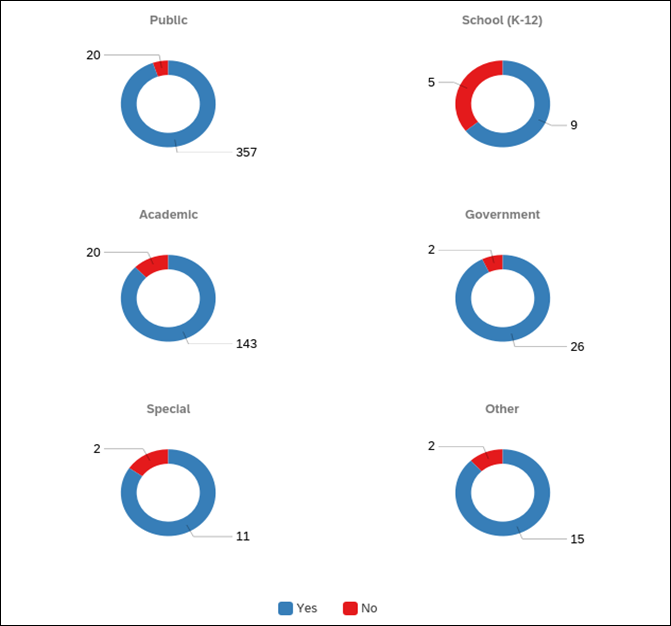

Figure 2

Q4: “Have you

received questions or suggestions…” by library type.

The researchers also compared results across library

types to explore any differences or similarities between them. Out of all types

of libraries, public libraries were the most likely to receive messages over

social media, and K-12 school libraries were the least likely. Figure 1 shows

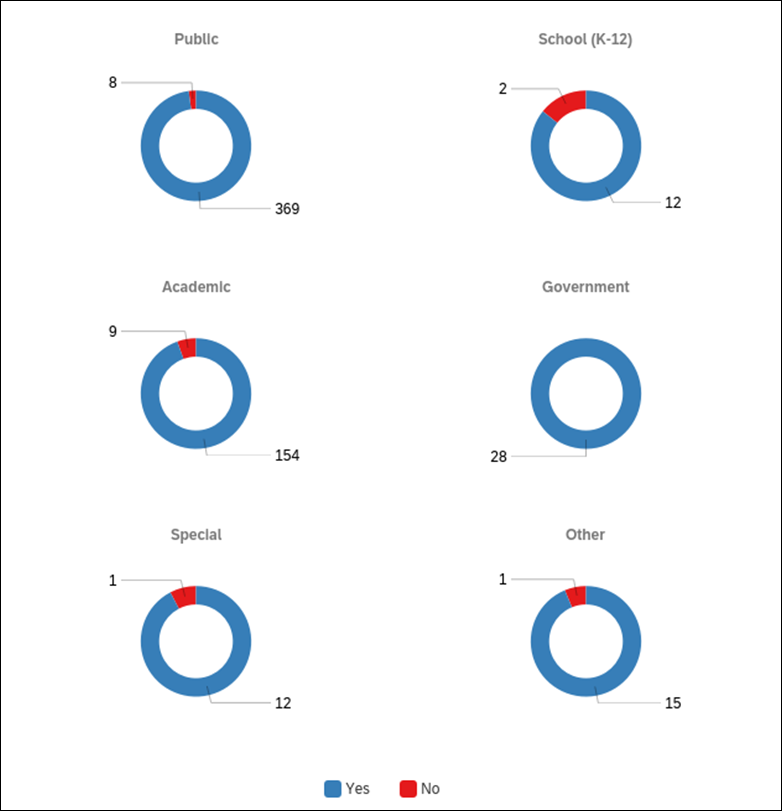

whether libraries receive questions or suggestions over social media, by

library type. Apart from government libraries, for whom all of those who

responded to the survey reported responding to social media questions or suggestions,

public libraries were also the most likely to respond to these inquiries, as

seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Q5: “Do you

respond to questions or suggestions…” by library type.

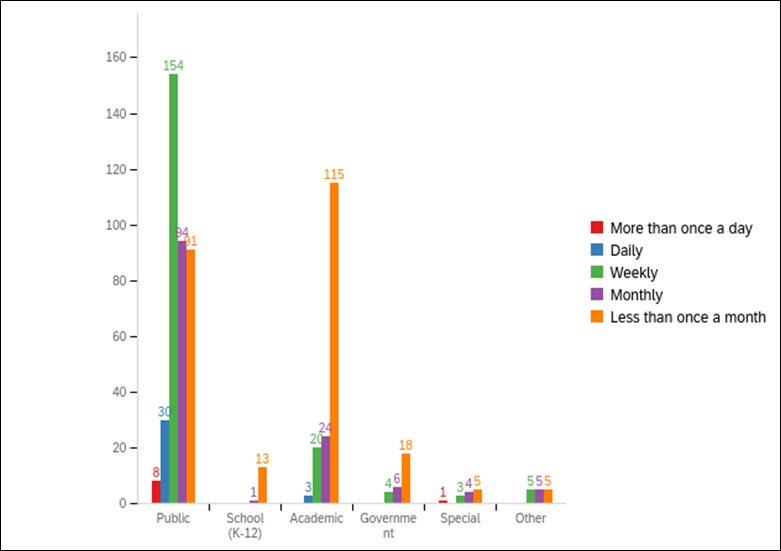

In addition to receiving a greater percentage of

messages over social media, public libraries also receive much more frequent

communication, the most common response stating they receive messages weekly,

whereas all other types of libraries predominantly reported receiving messages

less than once a month. Figure 4 shows frequency by library type.

Figure 4

Q6: Social media

contact frequency, by library type.

Types of libraries also differed in how they saw

social media messaging as affecting change and how they reported or tracked

questions or suggestions received over social media. Public libraries, for

instance, ranked Clarification (n=98) and Reach (n=69) as their two most

frequent changes, while academic libraries’ most frequent change was Nothing

(n=43). See Table 1 for the theme frequency according to library type.

Table 1

Q7: “What Has Changed

in Your Library Services or Spaces…” by Library Type

|

Code |

Public |

School (K-12) |

Academic |

Government |

Special |

Other |

Total |

|

Clarification |

98 |

2 |

31 |

5 |

2 |

5 |

143 |

|

Nothing |

67 |

1 |

43 |

7 |

4 |

2 |

124 |

|

Reach |

69 |

2 |

18 |

5 |

4 |

5 |

103 |

|

Service |

57 |

1 |

13 |

3 |

0 |

2 |

76 |

|

Marketing |

30 |

0 |

15 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

49 |

|

Collections |

26 |

1 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

33 |

|

Access |

19 |

1 |

12 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

33 |

|

N/A |

10 |

0 |

8 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

19 |

|

Policy |

9 |

0 |

6 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

16 |

|

Unclear |

5 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

9 |

|

Collaboration |

4 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

|

Restriction |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

5 |

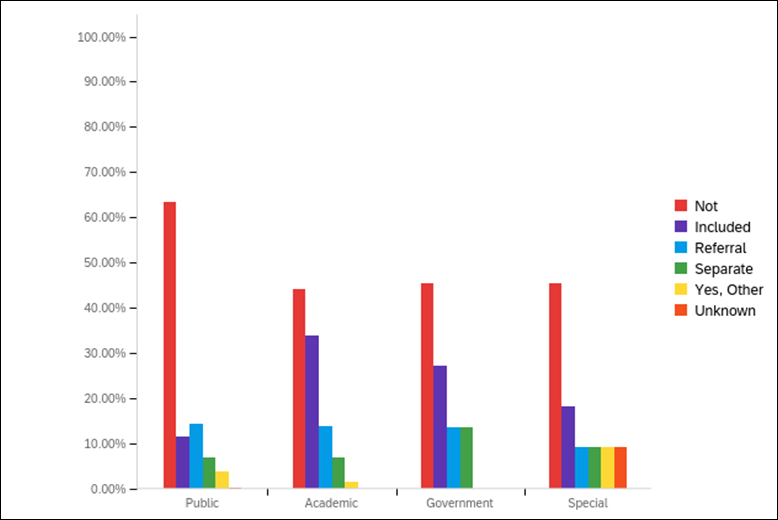

Though more respondents from public libraries

identified some manner of change resulting from social media messaging, they

were less likely to report or track these messages in any formal way. Whereas

around 45% of academic, government, and special libraries each report not

tracking social media messages, 66% of public libraries neither track nor refer

incoming questions or suggestions received on social media. Figure 5 shows

percentages of how each type of library tracks or reports questions or

suggestions received on social media.

Figure 5

Q8: Message

tracking or reporting, by library type.

Table 2

Q8: Message Tracking

or Reporting, by Library Type

|

Q8 |

Public |

|

School |

|

Acad. |

|

Gov. |

|

Special |

|

Other |

|

|

Not |

63.29% |

200 |

85.71% |

6 |

44.14% |

64 |

45.45% |

10 |

45.45% |

5 |

33.33% |

4 |

|

Referral |

14.24% |

45 |

0.00% |

0 |

13.79% |

20 |

13.64% |

3 |

9.09% |

1 |

0.00% |

0 |

|

Included |

11.39% |

36 |

0.00% |

0 |

33.79% |

49 |

27.27% |

6 |

18.18% |

2 |

58.33% |

7 |

|

Separate |

6.96% |

22 |

0.00% |

0 |

6.90% |

10 |

13.64% |

3 |

9.09% |

1 |

8.33% |

1 |

|

Yes, Other |

3.80% |

12 |

14.29% |

1 |

1.38% |

2 |

0.00% |

0 |

9.09% |

1 |

0.00% |

0 |

|

Unknown |

0.32% |

1 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

9.09% |

1 |

0.00% |

0 |

|

Total |

|

316 |

|

7 |

|

145 |

|

22 |

|

11 |

|

12 |

Discussion

Survey

results show that a library's social media presence provides a valuable patron

interaction point beyond being a platform for simply sharing content and

soliciting feedback. For many libraries, social media has joined other methods

of interaction—such as phone, email, face-to-face, etc.—as an integral service

point. Those libraries that provide even a modicum of interaction on a social

media platform are better at reaching their patrons where they are, and the

most engaged among them report connecting with their users in ways that might

not happen otherwise. While nearly 92% of respondents of Q4 acknowledge

receiving some manner of question or suggestion from a patron on social media,

nearly 97% of them report using their social media to address questions or

suggestions. More respondents reported responding than receiving, which may

suggest the use of social media to address questions or suggestions received

elsewhere, or it may be a result of multiple individuals on a social media team

having responsibility for receiving, reporting, and responding to messages.

This uncertainty is discussed further in this study’s limitations and

opportunities for future research.

Engaging With Questions and Suggestions

Across

all libraries, 59% receive at least one question or suggestion via social media

per month, and 37% receive at least one per week. For public libraries,

communication over social media is more frequent, with nearly 51% receiving at

least one question or suggestion per week. Other library types primarily report

receiving fewer than one per month, though with the exception of K-12 school

libraries, at least 25% report receiving one or more per month. Those libraries

that engage in proactive methods to garner social media communications have a more

positive experience in receiving and utilizing social media feedback. Among

libraries the authors identified as increasing social media reach in response

to messages received—a group including all types of libraries—the frequency of

received messages is greater, with 72% receiving at least one message per month

and 50% receiving at least one per week.

This study does not assess patron communication

tendencies, but rather the libraries’ response to social media interaction. In

response to Q7, 20% of survey respondents claimed that nothing changed, but

then went on to describe how social media has become a platform to receive and

respond to ready reference questions. The act of responding to these questions

constitutes a change in service: a new platform by which to communicate with a

patron base that may not have reached out via other methods. This change is

subtler than something collections or service-related, where a patron

explicitly asks for something not previously offered, and as a result the

library changes its offerings. Instead, the act of reaching out over social

media is the implicit ask—“Will you respond?”—and as

reported in the survey, the answer is not always “Yes.”

In a minority of cases, older, more traditional

methods of communication such as email or phone are preferred, and library

social media services have been restricted to direct patrons to reach out

through those official channels. A Wisconsin public library anticipated this

tendency, writing, “We also offer direct links to our website/events/registration

instead of just saying "go to our website.””

Some respondents also identified the tendency to

attract bad-faith interactions with “trolls” or individuals using the anonymity

of the internet to justify mean-spirited or hurtful criticism. Opening the door

to interaction on social media also invites these individuals to participate.

Across the board, survey respondents who identified this sort of behavior also

report ignoring or blocking the offenders.

In some cases, social media served as an impetus to

increase messaging mindfulness. Some survey respondents noted requests to

change certain phrasing to more acceptable terminology, both in functional

library tools—"feedback has influenced naming practices in our catalog”

from a Texas academic library—and on public-facing media platforms—“We became aware of...the term “Autism Acceptance” and

changed our signs and SM accordingly” from a Massachusetts public library.

Others said their social media interactions led to including depictions of a wider

variety of individuals when posting images.

The

quick feedback afforded to and expected by users of social media often make it

a good venue for suggestions, provided the library is open to receiving

feedback in this way. Several libraries identified an improvement in their

communication style after receiving social media feedback. “It helped me

identify where we can improve communication…what we include on flyers and

brochures [and] information we make available through social media.” Others

identify changing “where and when we post announcements,” with a goal of making

services “more customer friendly.”

Tracking and Reporting Practices

When it comes to incorporating social media comments

and suggestions into a tracking or reporting workflow, there are some notable

differences in how libraries handle this task. While public libraries report

receiving the most frequent communication via social media, they also report

having the least codified tracking structure for any questions or suggestions

received in that way.

One Washington academic library notes, “So far they

are few and far between, so not tracking currently.” This is a recurring theme

throughout the responses: many libraries share that the volume of social media

questions and suggestions is too low to warrant tracking. However, this

suggests that should the number of social media interactions increase, it might

be worth recording. As one Texas academic library responds: “I am in the

process of developing a social media engagement reporting schedule to help

track social media engagement in general. Since our engagement is typically

very low, there is not much to report or track, which is why this hasn't been

done in the past.”

Smaller libraries, too, identify less of a need to

track or report social media interactions. One Minnesota public library

responds: “If I received questions/suggestions, I would not track them. I might

report them to the city administrator. I am the ONLY librarian in the library.”

Similarly, from a Michigan public library, “We are small, so I report to our

Interim Manager.” In these cases, where incorporating social media comments

into reported reference statistics is perhaps unnecessary, they still see value

in referring the social media feedback up to an administrator.

There is a trend of directly informing others about social

media feedback but not incorporating it into existing structures. Several

libraries refer social media suggestions directly to administration, with 17

responses sharing any feedback directly with their director, dean, or senior

management. This may suggest that social media feedback carries more importance

than feedback received through traditional channels since it is afforded a

direct route to library administration.

One

of the study’s goals was to find out how social media interactions are managed,

including opportunities to track, report, and refer. Findings show that most

social media managers do not track questions received through social media

channels, such as through existing workflows like reference question reporting

or referring to other departments. Without this information, how could library

social media managers best support their continued use of these tools? Perhaps

new parameters such as measuring the quantity and quality of engagements and

changes to services or collections could be new, evidence-based parameters for

success. This data would help showcase the impact and intentionality of a

library’s social media presence, more so than other available analytics such as

number of followers, likes, or views.

Timeliness

Responses to this survey were clearly impacted by its

timing, distributed as it was in the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

During this worldwide event with major ramifications for the safety and

practicality of in-person library services, many libraries either added or

expanded their online presence, and social media communications became an

extension of this. One Pennsylvania public library remarked that social media

"helped us innovate pandemic services and work toward keeping popular ones

in a modified fashion." While this is one of 34 responses to Q7 or Q8

directly mentioning either COVID or the pandemic, any change to clarification,

reach, or virtual services would be a benefit to a patron base that was

incapable of visiting the library in person. Thus, we can assume that many more

of the suggestions and comments received by librarians were a direct result of

COVID-related communication needs.

As

libraries have reopened (and while some never closed), COVID-19 also led to

changes to physical spaces. One Minnesota K-12 school library received social

media feedback from students who "commented that they liked the reduced

seating in the learning commons" for COVID-related physical distancing

requirements, which had the unintended effect of "[allowing] them a more quiet area to work." Other libraries variously

reported boosting WiFi signals, adjusting hours of

operation, incorporating pop-up outdoor events, and other demonstrations of

flexibility in reaction to pandemic demands. What remains to be seen is how

these services and communication channels will change in a post-pandemic world.

Follow-up research is warranted to further explore the effects of COVID-19 on

libraries' social media use.

Limitations and Future Research

First, while the authors were elated at the number and

range of survey responses and the trends derived from commonalities in the

qualitative portions, the low number of responses from school (K-12),

government, special, and other libraries besides public and academic makes it

difficult to draw generalized conclusions from those library types. Any future

studies interested in one or more of those populations should target them

directly via their professional organizations, mailing lists, and interest

groups rather than large, generic organizations.

Also

in relation to survey responses, study limitations arose since the researchers

invited all who identified as library social media managers to participate;

there was no limit per library. Survey respondents’ self-identification as a

social media manager presented the possibility of a wide range of job duties

and expertise represented across all participants. In addition, multiple

responses from the same library could have affected the sample size, and add an

uncertainty about whether individuals responded according to their own

experience or assumed they were answering on behalf of their library.

Lastly,

the broad and exploratory nature of the qualitative portion of this survey led

to some confusion among the respondents. Both Q7 and Q8 were written in an ambiguous

way, so while some responses covered services, spaces, questions, and

suggestions, many more addressed just one or two of those aspects.

Additionally, there was room for interpretation when it came to our definitions

of "what has changed" in library services or spaces and how social

media interactions might be "tracked." Utilizing the coding data

generated in this study, future exploration into this topic might limit the amount of open-ended questions and instead provide a list of

options for both how things have changed and how social media interaction is

reported, with limited space to write in explanations or examples.

The

survey results and analysis reveal opportunities for deeper research regarding

library social media management. Future research questions might include:

●

The

authors noted a theme of social media messages having a faster path directly to

library administration. Do questions or suggestions from people using social

media get higher priority over those received through traditional reference

channels? A survey of library administrators as to their impression of social

media effectiveness may reveal additional insight.

●

There

was little agreement among libraries as to how to best track and report on

social media interaction. Further, there was great disparity between those

libraries claiming to get a lot out of social media interaction and those

claiming to get none. Are there trainings or competencies on library social

media best practices that should be developed for library social media

managers?

Conclusion

This

study shows a variety of practices related to communicating and social media,

including sharing, listening, tracking, and making changes. Although social

media is usually part of an overall communication strategy, it can become just

another mechanism to just share news and updates. Many libraries, however, are

using it as a resource to learn more from their patrons and communities to

better serve their population. This increases a library’s approachability and

reach.

Author Contributions

Jason

Wardell: Conceptualization (equal),

Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Investigation (equal),

Visualization (lead), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review &

editing (equal) Katy Kelly:

Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (equal),

Investigation (equal), Visualization (supporting), Writing – original draft

(equal), Writing – review & editing (equal)

References

Ahenkorah-Marfo, M., & Akussah, H. (2017). Information on

the go: Perspective of academic librarians on use of social media in reference

services. International Information &

Library Review, 49(2), 87-96. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572317.2016.1278190

American Library Association. (2018, June). Social media guidelines for public and academic libraries. https://www.ala.org/advocacy/intfreedom/socialmediaguidelines

Edison Research. (2021). The

Infinite Dial 2021. http://www.edisonresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/The-Infinite-Dial-2021.pdf

Howard, H. A., Huber, S., Carter, L. V., & Moore, E. A. (2018).

Academic libraries on social media: finding the students and the information

they want. Information Technology and

Libraries, 37(1), 8-18. https://doi.org/10.6017/ital.v37i1.10160

Katopol,

P. (2017). The library as a greedy institution. Library Leadership & Management, 31(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.5860/llm.v31i2.7251

Kliewer,

C. (2018). Library social media needs to be evaluated ethically. Public Services Quarterly, 14(2),

170–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228959.2018.1447418

Kushniryk,

A., & Orlov, S. (2021). ‘Follow us on Twitter’: How public libraries use

dialogic communication to engage their publics. Library & Information Science Research, 43(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2021.101087

OCLC WebJunction. (2018, February 13). Social media and libraries survey summary.

https://www.webjunction.org/news/webjunction/social-media-libraries-survey.html

Pew Research Center. (2021, April 7). Social media fact sheet. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/

Rogers, C. (2009, May 22). Social media, libraries, and Web 2.0: How

American libraries are using new tools for public relations and to attract new

users. Presented at the German Library Association Annual Conference: Deutscher Bibliothekartag 2009 in

Erfurt. https://dc.statelibrary.sc.gov/bitstream/handle/10827/6738/SCSL_Social_Media_Libraries_2009-5.pdf?sequence=1

Sulkow,

C., Ferretti, J. A., Blueher, W., & Simon, A.

(2019). #artlibraries: Taking the pulse of social

media in art library environments. Art

Documentation: Bulletin of the Art Libraries Society of North America, 38(2), 305–323. https://doi.org/10.1086/706630

Taylor & Francis Group (2014). Use

of social media by the library: Current practices and future opportunities [White

paper]. Taylor & Francis Group.

Trucks, E. (2019). Making social media more social: a literature review

of academic libraries’ engagement and connections through social media

platforms. In J. Joe & E. Knight (Eds.), Social media for communication and instruction in academic libraries. (pp.

1-16). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-8097-3.ch001

Appendix A

Survey

INVITATION TO PARTICIPATE IN RESEARCH

Surveys and Interviews

Research Project Title: Library Social Media Management

and Engagement

You have been asked to participate in a research

project conducted by (researchers) from (institution). We are looking for

managers of social media at all types of libraries in the United States to

answer a 5-minute survey with mostly yes or no questions. For the purposes of

this survey, we are defining “managers of social media” as any individual who

is responsible for monitoring or posting on social media on a library’s behalf.

All library social media managers are encouraged to respond; there is no limit

per library.

The purpose of this project is to better understand

the current use of social media by libraries to solicit and respond to

questions and feedback.

●

You should read

the information below, and ask questions about anything you do not understand,

before deciding whether or not to participate.

●

Your

participation in this research is voluntary. You have the right not to answer

any question and to stop participating at any time for any reason. Answering

the questions will take about 5 minutes.

●

You will not be

compensated for your participation.

●

All of the

information you tell us will be confidential.

●

If this is a

recorded interview, only the researcher and faculty advisor will have access to

the recording and it will be kept in a secure place.

●

If this is a

written or online survey, only the researcher and faculty advisor will have

access to your responses. If you are participating in an online survey: We will

not collect identifying information, but we cannot guarantee the security of

the computer you use or the security of data transfer between that computer and

our data collection point. We urge you to consider this carefully when

responding to these questions.

●

I understand

that I am ONLY eligible to participate if I am over the age of 18.

Please contact the following investigator with any

questions or concerns:

(Researcher and contact information)

If you feel you have been treated unfairly, or you

have questions regarding your rights as a research participant, please email (email

address) or call (phone).

2. Do you agree to participate in this survey?

●

Yes

●

No

3. Are you a manager of a library's social media

account(s)?

(Note: for the purposes of this survey, a

"manager" is anyone responsible for monitoring or posting on social media

on the library's behalf.)

●

Yes

●

No

4. Have you received questions or suggestions on your

library's social media?

●

Yes

●

No

5. Do you respond to questions or suggestions on your

library social media?

●

Yes

●

No

6. Approximately how often do you receive questions or

suggestions on your library's social media?

●

More than once a

day

●

Daily

●

Weekly

●

Monthly

●

Less than once a

month

7. What has changed in your library services or spaces

as a direct result of questions or suggestions received via social media?

8. How are these questions and suggestions reported

and/or tracked?

9. What type of library do you work for?

●

Public

●

School (K-12)

●

Academic

●

Government

●

Special

●

Other

10. In which state is your library located?

●

Included all 50

states, Washington D.C., and Puerto Rico

Appendix B

Timeline of the Survey Invitation Sharing to Each Communication Channel and Their

Approximate Reach

|

Invitation Date, 2021 |

Channel |

Members at Invitation Date, approx., if known |

|

April 28 |

Academic Library Association of Ohio (ALAO) listserv |

645 |

|

April 28 |

Ohio Library Council (OLC) Marketing and PR Division |

|

|

April 28 |

Ohio Library Support Staff Institute (OLSSI) |

|

|

April 28 |

Society of Ohio Archivists |

376 |

|

April 29 |

Academic Library Association of Ohio (ALAO)

Programming, Outreach, and Marketing Interest Group (PROMIG) listserv |

39 |

|

May 3 |

Ohio Educational Library Media Association (OELMA) |

|

|

May 3, May 10 |

OhioLINK May weekly updates |

|

|

May 6 |

OhioNET May newsletter |

|

|

May 18 |

Facebook Group: Association of College and Research

Libraries (ACRL) Library Marketing and Outreach Interest Group |

5,400 |

|

May 18 |

Facebook Group: Libraries & Social

Media |

13,400 |

|

May 18 |

American Library Association (ALA) Connect: ALA All

Members |

45,000 |

|

May 18 |

ALA Connect: ACRL Library Marketing and Outreach

Interest Group |

1,400 |

|

May 19 |

Medical Library Association |

|

|

May 19 |

Society of American Archivists |

6,369 |