Review Article

Library Instruction for

Graduate Nursing Students: A Scoping Review

Adelia Grabowsky

Health Sciences Librarian

Ralph Brown Draughon Library

Auburn University

Auburn, Alabama, United

States of America

Email: abg0011@auburn.edu

Katherine Spybey

Former Adjunct Professor

Nursing Department

Calhoun Community College

Decatur, Alabama, United

States of America

Email: katiespybey@gmail.com

Received: 7 Apr. 2022 Accepted: 17 Oct. 2022

![]() 2022 Grabowsky and Spybey. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2022 Grabowsky and Spybey. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30145

Abstract

Objective – The number of graduate nursing programs in the U.S. has increased

significantly in recent years. This scoping review seeks to examine the range

of literature discussing librarian instruction for graduate nursing students to

identity the types of studies being published, the characteristics of

instructional sessions, knowledge gaps which may exist, and the evidence

available for a subsequent systematic review evaluating instructional

effectiveness.

Methods – Guidelines established by the PRISMA statement for

scoping reviews (PRISMA-Scr) were used to conduct this review. Concepts for

library instruction and graduate nursing students were searched in six

databases as well as Google Scholar. The two authors used titles/abstracts and

when necessary, full-text to independently screen identified studies.

Conflicting screening decisions were resolved by discussion.

Results – Data was extracted from 20

sources. Thirteen of the sources were descriptions of classes or programs, one

was a program evaluation, two were mixed methods studies that looked at library

use and program support respectively but did not assess instruction, two were

surveys of students’ feelings and attitudes about instruction, and two were

quasi-experimental studies which included pre-post instruction quizzes. The

most popular format for library instruction was online (synchronous or

asynchronous) instruction. Most sources did not include information about the

timing or duration of instruction. In addition, most sources did not reference

instructional theory although a few mentioned aspects of instructional theory

such as active learning. Only one source mentioned using a specific model to

develop instructional content. While several sources mentioned assessment of

student learning, only four studies included the results of assessment.

Conclusions – Sources reporting on

instruction for graduate nursing students consisted primarily of descriptions

of programs or instructional sessions. Many of the descriptive studies lacked

essential information such as specifics of format, timing, and duration which

would aid replication at other institutions. Only four sources were research

studies that evaluated instructional effectiveness.

Introduction

The number of graduate

nursing programs in the U.S. as well as enrollment in those programs has been

increasing steadily (Jonas Philanthropies, 2015). Although librarians and

nursing faculty might imagine that students enter graduate school with

information literacy (IL) skills already fully developed, researchers have

found that many students, including those in graduate nursing programs,

struggle with finding, evaluating, and using information effectively (Robertson

& Felicilda-Reynaldo, 2015). Therefore, graduate nursing students may

benefit from librarian-led instruction intended to improve information literacy

skills.

While librarians might

consider using the same information and instructional techniques employed in

undergraduate nursing classes, graduate students tend to differ from

undergraduates in meaningful ways. Graduate nursing students are likely to be

older, may have been out of school for many years, and may have additional

family or work responsibilities (Salani et al., 2016). In addition, graduate

nursing students are expected to develop more advanced information literacy

skills than undergraduates to facilitate translating evidence into practice,

identifying gaps in practice, and disseminating their scholarship (American

Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2021). Finally, as adult learners,

graduate nursing students may have a greater need for library instruction that

allows them to be self-directed, to have their prior experience taken into

account, and to understand why they are learning and how the new knowledge will

be helpful in real-world situations (Knowles et al., 1998; Ross-Gordon et al.,

2017).

Aims

This scoping review seeks

to identity and summarize the published literature related to library

instruction provided to graduate nursing students. The following research

questions guided the study:

- What types of studies are being published?

- What characteristics of instructional sessions

are included in published literature?

Methods

Guidelines established by

the PRISMA statement for scoping reviews (PRISMA-Scr) were used to conduct this

review (Tricco et al., 2018). No protocol was prepared for the review. One

author (AG), a health sciences librarian with prior experience creating

searches for systematic and scoping reviews, developed and executed all

searches. Six databases were searched on July 30, 2019 with concepts for

library instruction and graduate nursing students along with related synonyms

and subject headings (see Appendix A for complete searches). CINAHL; Medline;

ERIC; Library Literature & Information Science Index (H.W. Wilson); and

Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts were searched

concurrently though the EBSCO interface while Library & Information Science

Abstracts (LISA) was searched through the ProQuest interface. The searches were

rerun on December 7, 2021 to update content before publication submission. Hand

searching consisted of examining the reference lists of reviews included in the

search results and screening the first 100 results of a search run in Google

Scholar. All results were exported to an EndNote library (Version X9). After

deduping, sources were exported to Excel spreadsheets for screening.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Types of Participants

The

population of interest was graduate nursing students. Studies that included

only undergraduate students or professional nurses were excluded; however,

studies that involved more than one level of student (e.g., undergraduates and

graduate students) or more than one type of student (e.g., nursing and pharmacy

students) were included as long as specific information about graduate nursing

students could be extracted.

Concept

Sources

had to include some type of librarian-led instruction. That instruction could

be provided wholly by the librarian(s) or in partnership with other

institutional faculty or staff. There were no restrictions on format of

instruction; sessions could be provided in-person or virtually, and either

synchronously or asynchronously.

Context

Due

to the change from print-focused to electronic resources beginning in the late

1990s and subsequent changes to library instruction, sources had to have been

published in or after 1994.

Types of sources of evidence

No

restrictions were placed on type of source. Book reviews, article reviews,

editorials, and evidence syntheses were excluded. All other source types

including articles, book chapters, dissertations, and theses were included. Due

to language restrictions of the reviewers and lack of funding for translation

services, all sources had to be written in English.

Screening

The

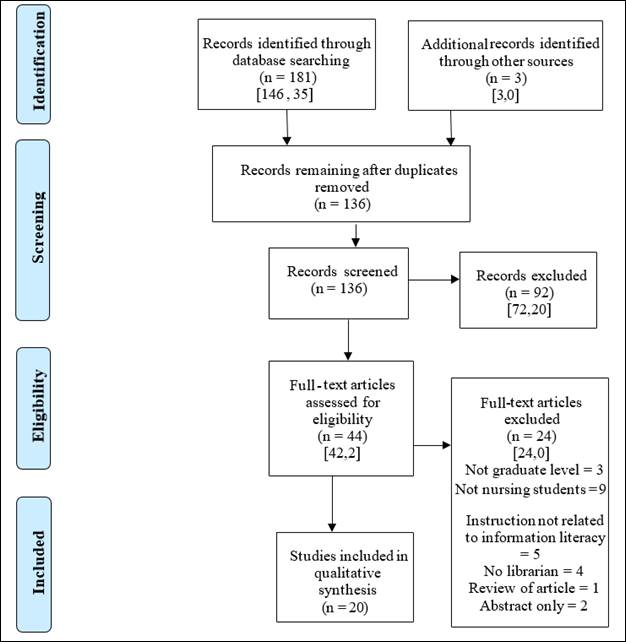

number of sources screened at each stage is shown in Figure 1. Numbers in parentheses are the total of the

initial search and the bridge search. Separate figures for each search are

provided in square brackets. At each level

(title/abstract and full-text) the two authors independently screened sources,

then met to compare decisions. Conflicting screening decisions were resolved by

discussion. After the full-text screening, 20 sources were retained for

synthesis.

Data Extraction

A

data extraction form was created using Excel. Variables on the form included

population; location; extent of instruction (class or program);

standards/guidelines/theories used to develop

instruction;

format, timing, and duration of instruction; content taught; additional support

offered; methodology; assessment; and additional notes (see Appendix B). One

author (AG) extracted data from each source and the second author (KS) checked

the extracted data for accuracy and completeness.

Results

Overview of Sources

The 20 sources included in

this review were primarily journal articles (n=19; Bernstein et al., 2020;

Dorner et al., 2001; Francis & Fisher, 1995; Guillot & Stahr, 2004;

Guillot et al., 2010; Hinegardner & Lansing, 1994; Hodson-Carlton & Dorner,

1999; Honey et al., 2006; Layton & Hahn, 1995; Leasure et al., 2009;

Lemley, 2016; Milstead & Nelson, 1998; Schilperoort, 2020; Thompson, 2009;

Welch et al., 2016; Whitehair, 2010; Whiting & Orr, 2013; Wills et al.,

2001; Wimmer et al., 2014). The one exception was a book chapter (Deberg,

2014). Publication dates ranged from 1994 to 2020 with zero to two publications

each year. Most instruction took place in the United States (n=18; Bernstein et

al., 2020; Deberg, 2014; Dorner et al., 2001; Francis & Fisher, 1995;

Guillot & Stahr, 2004; Guillot et al., 2010; Hinegardner & Lansing,

1994; Hodson-Carlton & Dorner, 1999; Layton & Hahn, 1995; Leasure et

al., 2009; Lemley, 2016; Milstead & Nelson, 1998; Schilperoort, 2020; Welch

et al., 2016; Whitehair, 2010; Whiting & Orr, 2013; Wills et al., 2001;

Wimmer et al., 2014), although there was one source from Canada (Thompson, 2009) and one from New

Zealand (Honey et al., 2006).

From: Moher

D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G., The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews

and Metanalyses: The PRISMA

Statement. PLoS Med 6(7):

e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.

For more

information, visit www.prisma-statement.org.

Figure

1

PRISMA

flow diagram.

Four sources included

instruction for more than one level of student. One of the four included Master’s,

DNP, and PhD students (Whitehair,

2010), two included Master’s and PhD students (Francis & Fisher, 1995;

Layton & Hahn), and one included Master’s and DNP students (Lemley, 2016).

The remaining sources included only one level of students. Master’s was the most common (n=9; Dorner et al., 2001;

Guillot & Stahr, 2004; Guillot et al., 2010; Hinegardner & Lansing,

1994; Hodson-Carlton & Dorner, 1999; Honey et al., 2006; Schilperoort,

2020; Thompson, 2009; Wills et al., 2001) followed by PhD (n=3; Milstead &

Nelson, 1998; Welch et al., 2016; Wimmer et al., 2014) and DNP (n=3; Bernstein

et al., 2020; Deberg, 2014; Whiting & Orr, 2013). The remaining source referred only to

graduate nursing students without indicating what level(s) were included

(Leasure et al., 2009).

Characteristics of Sources (see

Appendix B)

Format of Instruction

The 20 identified sources

included descriptions of format for 21 classes and programs. The most popular

format for library instruction was virtual (n=7); however, only one source used

online synchronous instruction (Wimmer et al., 2014). Other virtual options

included interactive tutorials (n=4; Dorner et al., 2001; Hodson-Carlton &

Dorner, 1999; Schilperoort, 2020; Welch et al., 2016), videos (n=1; Deberg, 2014), and

a static webpage (n=1; Milstead & Nelson, 1998). Five additional sources

used hybrid methods with both virtual and face-to-face (F2F) components. Two of

the five used F2F followed by online tutorials (Honey et al., 2006; Leasure et

al., 2009), one used F2F followed by a recording (Deberg, 2014), one used F2F

followed by optional individual virtual sessions (Guillot & Stahr, 2004),

and one used both F2F and synchronous instruction followed by optional

individual sessions (Whitehair, 2010). Four

sources included only F2F instruction; however, it is important to note that three

of those four were from 1994 and 1995, the earliest years included in this

review (Francis & Fisher, 1995; Hinegardner & Lansing, 1994; Layton

& Hahn, 1995). The fourth

F2F source occurred later but involved instruction on SPSS using library

computers (Thompson, 2009). Three

of the remaining five sources reported on librarians who were embedded in a

course or courses throughout the semester (Guillot et al., 2010; Lemley, 2016;

Wills et al., 2001). The final two did not indicate the format of instruction

(Bernstein et al., 2020; Whiting & Orr, 2013).

Timing of Instruction

Three sources involved

embedded librarians (Guillot et al., 2010; Lemley, 2016; Wills et al., 2001)

and one a static webpage (Milstead & Nelson,

1998) so instruction could be considered to be available throughout the

class. There were 17 classes described in the remaining 16 studies. There was

no indication of when instruction took place during the semester for eight of

those classes (Deberg, 2014; Francis & Fisher, 1995; Guillot & Stahr,

2004; Hinegardner & Lansing, 1994; Layton & Hahn, 1995; Leasure et al.,

2009; Thompson, 2009; Whiting & Orr, 2013). The remaining nine reported

instruction which took place early in the semester, i.e., before class started

or within the first month (Bernstein et al., 2020; Deberg, 2014; Dorner et al.,

2001; Hodson-Carlton & Dorner, 1999; Honey et al., 2006; Schilperoort,

2020; Welch et al., 2016; Whitehair, 2010; Wimmer et al., 2014). In addition, some authors reported that

instruction was tied to course assignments or course content (Bernstein et al.,

2020; Deberg, 2014; Dorner et al., 2001; Guillot & Stahr, 2004; Hinegardner

& Lansing, 1994; Hodson-Carlton & Dorner, 1999; Thompson, 2009), that

library assignments were required/graded (Francis & Fisher, 1995;

Schilperoort, 2020), and that assistance

(Guillot et al., 2010) or tutorials (Dorner

et al., 2001) were provided at point of need. Finally, seven authors reported

inclusion in the course learning management system which provided access to

syllabi, assignments, discussion boards, and class email lists (Dorner et al.,

2001; Guillot et al., 2010; Lemley, 2016; Whitehair, 2010; Whiting & Orr,

2013; Wills et al., 2001; Wimmer et al., 2014).

Duration of Instruction

Very few sources reported

how long instruction lasted. Most that did mention duration were

discussing either F2F sessions or the F2F session of hybrid instruction.

Durations reported included two mentions each of one-hour sessions (Guillot

& Stahr, 2004; Whitehair, 2010), two-hour sessions (Francis & Fisher,

1995; Layton & Hahn, 1995), and three-hour sessions (Hinegardner &

Lansing, 1994; Thompson, 2009). Only Schilperoort (2020) mentioned

the length of instructional

tutorials, reporting an average time of 15 to 30 minutes to complete the

self-paced tutorial.

Content of Instruction

Fourteen

of the 20 sources included introducing students to databases, in many cases

mentioning specific health science databases such as CINAHL and Medline (Bernstein et al., 2020;

Deberg, 2014; Dorner et al., 2001; Francis & Fisher, 1995; Guillot &

Stahr, 2004; Hinegardner & Lansing, 1994; Honey et al., 2006; Layton &

Hahn, 1995; Leasure et al., 2009; Lemley, 2016; Schilperoort, 2020; Welch et

al., 2016; Whitehair, 2010; Wills et al., 2001). Nine of those 14 sources also included

specific instructional content related to searching skills such as choosing

keywords, finding subject headings, and using Boolean operators or filters (Bernstein et al., 2020;

Dorner et al., 2001; Francis & Fisher, 1995; Hinegardner & Lansing,

1994; Layton & Hahn, 1995; Leasure et al., 2009; Lemley, 2016;

Schilperoort, 2020; Whitehair, 2010). Although all instruction might be

assumed to discuss library services, 11 sources explicitly mention introducing

library services in general or specific services such as how to access

full-text, use interlibrary loan or contact a librarian for help (Guillot & Stahr, 2004;

Guillot et al., 2010; Honey et al., 2006; Layton & Hahn, 1995; Leasure et

al., 2009; Lemley, 2016; Milstead & Nelson, 1998; Thompson, 2009;

Whitehair, 2010; Whiting & Orr, 2013; Wimmer et al., 2014). Five instructors included content about

citing sources (Dorner et al., 2001; Guillot et al., 2010; Lemley, 2016; Welch

et al., 2016; Whiting & Orr, 2013), and four included instruction on

evaluating research sources (Bernstein et al., 2020; Dorner et al., 2001;

Hodson-Carlton & Dorner, 1999; Leasure et al., 2009).

Additional

content mentioned more than once included: bibliographic management software

(n=3; Hinegardner & Lansing, 1994; Leasure et al., 2009; Welch et al.,

2016), developing research questions (n=3; Deberg, 2014; Guillot et al., 2010;

Welch et al., 2016), evaluating evidence/levels of evidence (n=3; Deberg, 2014;

Lemley, 2016; Schilperoort, 2020), and resources to find research instruments

(n=2; Dorner et al., 2001; Francis & Fisher, 1995). Finally, there was content mentioned by

only one author including current awareness services (Whitehair, 2010), data concepts and

using SPSS (Thompson, 2009), off-campus access (Francis & Fisher, 1995),

and in a pre-2000 source, how to use email and the Internet (Layton & Hahn,

1995).

Additional Support

In

many cases students were offered additional support beyond the actual instructional

session(s). The most common type of support offered was online discussion

boards/rooms within learning management systems (n=5; Dorner et al., 2001;

Hodson-Carlton & Dorner, 1999; Lemley, 2016; Whiting & Orr, 2013; Wills

et al., 2001). Other support

included encouraging students to contact a librarian or a library help desk

with questions (n=3; Lemley, 2016; Thompson, 2009; Whitehair, 2010), offering

individual sessions (n=3; Bernstein et al., 2020; Deberg, 2014; Wills et al.,

2001), holding chat sessions for group help (n=2; Dorner et al., 2001;

Hodson-Carlton & Dorner, 1999), sending follow-up emails (n=2; Guillot

& Stahr, 2004; Guillot et al., 2010), providing information about

additional training opportunities (n=2; Honey et al., 2006; Leasure et al.,

2009), offering a research guide (n=1; Wimmer et al., 2014), and providing a

brochure (n=1; Honey et al., 2006).

Assessment of Instruction

Most of the sources (n=16)

did not assess the effectiveness of library instruction. Instead, authors

provided descriptions of how instruction was implemented in a specific class or

classes (n=6; Deberg, 2014; Guillot & Stahr, 2004; Guillot et al., 2010; Hinegardner

& Lansing, 1994; Wills et al., 2001; Wimmer et al., 2014), how instruction

was implemented in a new program of study (n=3; Francis & Fisher, 1995;

Honey et al., 2006; Lemley, 2016), or how instruction was implemented in both a

program and one or more specific classes (n=7; Dorner et al., 2001; Layton

& Hahn, 1995; Leasure et al., 2009; Milstead & Nelson, 1998; Welch et

al., 2016; Whitehair, 2010; Whiting & Orr, 2013). Three of those 16 sources were research

studies, but the research was intended to assess library use (Honey et al., 2006), students’

satisfaction with library services and resources (Whiting & Orr, 2013), or

the practicalities of providing instruction (Guillot & Stahr, 2004) rather

than instructional effectiveness.

Several authors did

mention assessing the effectiveness of instruction with varied means including

pre/posttests and evaluations; however, no results of assessment were provided

(Deberg, 2014; Dorner et al., 2001; Francis & Fisher, 1995; Layton &

Hahn, 1995; Welch et al., 2016). Four

authors provided anecdotal evidence of instructional success derived from

informal feedback from faculty or students (Deberg, 2014; Dorner et al., 2001),

course evaluations (Guillot et al., 2010), or colleagues at the reference desk

(Francis & Fisher, 1995).

Only four sources were

research studies assessing the effectiveness of library instruction. Two were

quasi-experimental studies utilizing pre and posttests of knowledge with

additional open-ended questions about student confidence (Hodson-Carlton &

Dorner, 1999; Schilperoort, 2020). The

other two studies surveyed students about their feelings and attitudes

concerning instruction (Bernstein et al., 2020; Thompson, 2009). Results of the research studies

assessing instructional effectiveness are shown in Table 1. There were mixed

results from surveys of student confidence, with three studies reporting

increased confidence (Bernstein et al., 2020; Hodson-Carlton & Dorner,

1999; Schilperoort, 2020) and one study reporting students almost equally

divided among more confident and less confident (Thompson, 2009). Both studies with pre and postquizzes

reported that the percentage of correct answers increased on the postquiz

(Hodson-Carlton & Dorner, 1999; Schilperoort, 2020).

Learning Theories/Standards/Guidelines

Fourteen

of the 20 sources did not mention using any standards, guidelines, or theories

to inform development of instructional content (Dorner et al., 2001; Francis & Fisher,

1995; Guillot & Stahr, 2004; Hinegardner & Lansing, 1994;

Hodson-Carlton & Dorner, 1999; Layton & Hahn, 1995; Leasure et al.,

2009; Lemley, 2016; Milstead & Nelson, 1998; Thompson, 2009; Welch et al.,

2016; Whiting & Orr, 2013; Wills et al., 2001; Wimmer et al., 2014). In the remaining six sources, two

authors mentioned library standards with Honey et al. (2006) referencing the Australian and

New Zealand Information Literacy Framework (Bundy, 2004) and Guillot et al. (2010) referencing both the

Association of Colleges and Research Libraries (ACRL, 2000) Information

Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education and the ACRL (2008)

Standards for Distance Learning Library Services. Three authors referenced

nursing standards with Bernstein et al. (2020) and Deberg (2014) citing the Essentials

of Doctoral Education for Advanced Nursing Practice (American Association of Colleges of

Nursing, 2006) and Whitehair (2010) citing the Practice Doctorate Nurse

Practitioner Entry-Level Competencies (National Panel for NP Practice

Doctorate Competencies, 2006).

Only

two authors mentioned using a specific learning model or theory to develop

instructional content. Whitehair (2010)

used both the student-centered model of Kraft and Androwich and Kuhlthau’s Model

of the Information Search Process. Schilperoort (2020) mentioned using both constructivist learning theory

and andragogy (adult learning theory) to develop an interactive tutorial. Six

additional authors (Dorner et al., 2001; Francis & Fisher, 1995;

Hinegardner & Lansing, 1994; Hodson-Carlton & Dorner, 1999; Layton

& Hahn, 1995; Leasure et al., 2009; Welch et al., 2016) did mention

elements such as active learning, hands-on learning, point-of-need instruction,

or accommodating different skill levels which would be consistent with adult

learning theory or constructivist approaches (Knowles

et al., 1998; Ross-Gordon et al., 2017).

Table 1

Results of Research Studies

Assessing Instructional Effectiveness

|

Population, Location |

Methodology |

Specifics |

Results of Assessment |

|

Surveys |

|||

|

Bernstein et al., 2020, DNP Students, United States |

Survey of student feelings and attitudes |

No indication of how many students completed the

survey. Results were given as broad statements rather than

as numbers or percentages. |

Most students felt they understood the components of

nursing literature. Most students felt confident in using databases to

find relevant literature. Students valued the integration of the library and

the writing center into the class and felt both should be included in future

classes. |

|

Thompson, 2009, Master’s students, Canada |

Survey of students’ feelings and attitudes |

No indication of how many students completed the

survey. Results were given as broad statements rather than

as numbers or percentages |

Most students agreed content was relevant. Students were divided about whether the class

increased their comfort with undertaking future quantitative projects. Students were divided about whether they felt more

comfortable reading and interpreting quantitative research. Most students felt the assignment was too difficult. |

|

Quasi-Experimental Studies |

|||

|

Hodson-Carlton & Dorner, 1999, Master’s students, Indiana |

Quasi-experimental (pre & postquiz plus open-ended questions) |

30 students took the prequiz and 24 took the

postquiz. (6 students did not complete the course so did not take the

post-quiz). |

88% (21/24) answered the 6 post-module questions

correctly compared to 63% (19/30) pre-module. |

|

Schilperoort, 2020, Master’s students, California |

Quasi-experimental (pre-post quiz plus survey of confidence with some open-ended

questions) |

59 students completed the pre and postquiz. 57 were

required to do so as part of a class, the other 2 chose to complete the

module voluntarily. 13 students provided additional comments. |

The percentage of correct answers increased on the

post-test for each of 5 questions. The biggest change (+46%) occurred in a

question asking students to rank by level of evidence. All students felt much more (49%) or somewhat more

(51%) confident in their ability to identify high-level research. All students felt much more (59%) or somewhat more

(41%) confident in their ability to use library resources to find various

types of evidence. Additional comments were positive. |

Challenges and Benefits

Some

challenges seemed to be almost universal while others were related to specific

types of instruction. The need for collaboration between nursing faculty and

librarians was mentioned by almost all authors (Bernstein et al., 2020; Deberg, 2014; Dorner

et al., 2001; Francis & Fisher, 1995; Guillot & Stahr, 2004; Guillot et

al., 2010; Hodson-Carlton & Dorner, 1999; Honey et al., 2006; Layton &

Hahn, 1995; Leasure et al., 2009; Lemley, 2016; Schilperoort, 2020; Welch et

al., 2016; Whitehair, 2010; Wimmer et al., 2014). In contrast, the

time-consuming aspects of instruction were mentioned primarily when discussing

embedded librarianship (Guillot et al., 2010; Lemley, 2016) or when offering

individual consultations (Bernstein et al., 2020; Deberg, 2014; Guillot &

Stahr, 2004). Dorner et al. (2001) also mentioned time as a

challenge when discussing the need to update videos frequently because of

database interface changes, a problem echoed in Schilperoort’s (2020) recommendation to review and

update tutorials at the beginning of each semester or use. One benefit

mentioned for tutorials is that even when created for a specific class, they

can also be offered as standalone sources of instruction (Hodson-Carlton &

Dorner, 1999; Schilperoort, 2020). Other

challenges reported for embedded librarianship include unrealistic expectations

of students (Guillot et al.,

2010) and role confusion, i.e., students asking questions of the librarian

which should be directed to nursing faculty (Guillot et al., 2010; Lemley,

2016). Benefits of embedded

librarianship included extended rapport with students (Guillot et al., 2010), the ability to be proactive (Lemley, 2016), and the ability to

broadcast messages to an entire class (Guillot et al., 2010; Lemley, 2016).

Other

instructional challenges mentioned include difficulties in providing equal

access to off-campus students (Dorner et al., 2001; Francis & Fisher, 1995;

Milstead & Nelson, 1998), technological costs associated with virtual

instruction (Guillot &

Stahr, 2004), and nursing faculty turnover (Dorner et al., 2001; Lemley, 2016).

Discussion

This scoping review sought to identify and summarize literature on

librarian-led instruction for graduate nursing students. Like previous research

(Salani et al., 2016), many of the reviewed sources suggest that the

needs of graduate nursing students differ from those of undergraduates in

multiple ways. Graduate nursing students tend to be older (Guillot & Stahr,

2004; Honey et al., 2006; Whiting & Orr, 2013) and to be working while

attending school (Dorner et al., 2001; Francis & Fisher, 1995; Guillot

& Stahr, 2004; Honey et al., 2006; Thompson, 2009; Whitehair, 2010; Whiting

& Orr, 2013). In addition, many graduate students have been out

of school for several years (Guillot & Stahr, 2004; Guillot et al., 2010;

Lemley, 2016; Whitehair, 2010; Whiting & Orr, 2013) and may have increased

family responsibilities (Guillot & Stahr, 2004; Whitehair, 2010).

Sources reporting on library instruction for graduate nursing students

consisted primarily of case reports, i.e., descriptions of instructional

sessions, tutorials, or programs rather than research studies evaluating

instructional effectiveness. Descriptions, particularly of new programs or

classes, can be helpful for librarians looking for different ways to approach

instruction, however, these descriptions often lacked details which would aid

in replicating library sessions or tutorials at other institutions. Although

all sources provided some information about instructional content and most

sources indicated the format of instruction, in many cases, other information

such as timing and duration which would assist in replicating the session was

missing.

Although several authors mentioned assessing instructional

effectiveness, few reported assessment results which could also aid in

replication decisions. In addition, the studies that did assess results varied

in significant ways. Two looked only at student’s feelings and attitudes

(Berstein et al., 2020; Thompson, 2009) which provides an incomplete measure of

effectiveness. The remaining two studies assessed both changes in knowledge and

attitude (Hodson-Carlton & Dorner, 1999; Schilperoort, 2020) which offers a

more complete assessment of learning. Although published 21 years apart, both

of the studies reported on the creation of a Web-based, point-of-need tutorial.

The older tutorial was intended to teach students to evaluate the quality of

websites, while the newer taught students to find evidence based information

and evaluate levels of evidence. Both studies reported an increase in student

knowledge after instruction.

Finally, although authors may have developed instruction and assessment

based on learning theories, standards, or guidelines, with a few exceptions,

there was little indication of which standards and/or theories were used and

how those standards/theories influenced instructional development.

Implications

Findings illustrate the need for librarians to provide more detail in

published class descriptions so that sessions can be replicated by others. Also

helpful would be more explicit information about instructional theories,

standards, or guidelines used to develop class content. More importantly,

librarians should consider adopting or creating assessment strategies to

determine the effectiveness of instruction for graduate nursing students, and

then publish the results of those assessments for the benefit of others. Only a

robust assortment of published assessment studies will enable a clearer

understanding of the effectiveness of library instruction for graduate nursing

students.

Limitations

Searching always involves compromise between comprehensiveness (finding

all relevant sources) and precision (finding a minimum of irrelevant sources).

This study sought to err on the side of comprehensiveness in two ways: (a) by

searching both subject headings and keywords in the title, abstract, and

subject heading fields and (b) by using compound searching (X AND Y) rather

than quoted phrase searching (“X Y”).

However, there are still limitations to the search. For example, there

may be other words or phrases used in the literature to refer to graduate

nursing students or library instruction that were not included in this search

strategy. In addition, search results were limited to results in English, which

would have limited the inclusion of studies completed outside the United

States.

Conclusion

This scoping review

examining published literature of librarian-led instruction for graduate nursing

students found that most of the sources were descriptions of classes or

programs which did not report any results from measures of instructional

effectiveness. An additional three sources evaluated programs or library use

but did not assess instruction. All sources reported some characteristics of

instructional sessions, but few provided enough information to allow others to

accurately replicate instruction at other institutions. Only four sources

provided measures of instructional effectiveness. Two included surveys of

students’ feelings and attitudes about instruction, and two were

quasi-experimental studies which included pre-post knowledge quizzes. The lack

of evidence related to the effectiveness of librarian-led instruction for the

population of graduate nursing students reveals a gap in library research and

suggests there is insufficient evidence to warrant a systematic review

evaluating this topic.

Author Contributions

Adelia Grabowsky: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis,

Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft,

Writing – review & editing Katherine Spybey: Conceptualization, Data

curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing

References

*References included in

scoping review

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2006). The essentials

of doctoral education for advanced practice nursing. https://www.pncb.org/sites/default/files/2017-02/Essentials_of_DNP_Education.pdf

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2021). The essentials:

Core competencies for professional nursing education. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/AcademicNursing/pdf/Essentials-2021.pdf

Association of College and Research Libraries. (2000). Information

literacy competency standards for higher education. https://alair.ala.org/handle/11213/7668

Association of College and Research Libraries. (2008). Standards for

distance learning library services. https://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/guidelinesdistancelearning

*Bernstein, M., Roney, L., Kazer, M. & Boquet, E. H. (2020).

Librarians collaborate successfully with nursing faculty and a writing centre

to support nursing students doing professional doctorates. Health

Information and Libraries Journal, 37, 240-244. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12327

Bundy, A. (2004). Australian and New Zealand information literacy

framework, https://www.utas.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/79068/anz-info-lit-policy.pdf

*Deberg, J. (2014). Reflections on involvement in a graduate nursing

curriculum. In A. E. Blevins (Ed.), Curriculum-based library instruction (pp.

165-170). Rowman & Littlefield.

*Dorner, J. L., Taylor, S. E. & Hodson-Carlton, K. (2001).

Faculty-librarian collaboration for nursing information literacy: A tiered

approach. Reference Services Review, 29(2), 132-40. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320110394173

*Francis, B. W. & Fisher, C. C. (1995). Multilevel library

instruction for emerging nursing roles. Bulletin of the Medical Library

Association, 83(4), 492-8.

*Guillot, L. & Stahr, B. (2004). A tale of two campuses: Providing

virtual reference to distance nursing students. Journal of Library

Administration, 41(1-2), 139-52. https://doi.org/10.1300/J111v41n01_11

*Guillot, L., Stahr, B. & Meeker, B. J. (2010). Nursing faculty

collaborate with embedded librarians to serve online graduate students in a

consortium setting. Journal of Library & Information Services in

Distance Learning, 4(1/2), 53-62. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332901003666951

*Hinegardner, P. G. & Lansing, P. S. (1994). Nursing informatics

programs at the University of Maryland at Baltimore. Bulletin of the Medical

Library Association, 82(4), 441-3.

*Hodson-Carlton, K. & Dorner, J. L. (1999). An electronic approach

to evaluating healthcare web resources. Nurse Educator, 24(5),

21-6. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006223-199909000-00013

*Honey, M., North, N., & Gunn, C. (2006). Improving library services

for graduate nurse students in New Zealand. Health Information and Libraries

Journal, 23(2), 102-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2006.00639.x

Jonas Philanthropies. (2015). New AACN data confirms enrollment surge

in schools of nursing. https://tinyurl.com/y3u262gd

Knowles, M. S., Holton, E. F., & Swanson, R. A. (1998). The adult

learner (5th ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann.

*Layton, B. & Hahn, K. (1995). The librarian as a partner in nursing

education. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, 83(4),

499-502.

*Leasure, A. R., Delise, D., Clifton, S. C., & Pascucci, M. A.

(2009). Health information literacy: Hardwiring behavior through multilevels of

instruction and application. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 28(6),

276-82. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCC.0b013e3181b4003c

*Lemley, L. (2016). Virtual embedded librarianship program: A personal

view. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 104(3), 232-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.104.3.010

*Milstead, J. A., & Nelson, R. (1998).

Preparation for an online asynchronous university doctoral course: Lessons

learned. Computers in Nursing, 16(5), 247-58.

National Panel for NP Practice Doctorate Competencies. (2006). Practice

doctorate nurse practitioner entry-level competencies. https://www.pncb.org/sites/default/files/2017-02/NONPF_DNP_Competencies.pdf

Robertson, D. S. & Felicilda-Reynaldo, R. F. (2015). Evaluation of graduate nursing students' information literacy

self-efficacy and applied skills. The Journal of Nursing Education, 54(3,

Suppl), S26-S30. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20150218-03

Ross-Gordon, J. M., Rose, A. D., & Kasworm, C. E. (2017). The adult

learner. In Foundations of adult and continuing education (pp. 215-253).

Jossey-Bass.

Salani, D., Albuja, L. D., & Azaiza, K. (2016). The keys to success

in doctoral studies: A preimmersion course. Journal of Professional Nursing,

32(5), 358-363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2016.01.005

*Schilperoort, H. M. (2020). Self-paced tutorials to support

evidence-based practice and information literacy in online health sciences

education. Journal of Library & Information Services in Distance

Learning, 14(3-4), 278-290. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2021.1873890

*Thompson, K. (2009). Torturing nurses with data: Building a successful

quantitative research module. IASSIST Quarterly, 33(3), 6-9. https://doi.org/10.29173/iq112

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H.,

Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl,

E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson,

M. G., Garritty, C., . . . Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping

reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal

Medicine, 169(7), 467-73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

*Welch, S., Cook, J. & West, D. (2016). Collaborative design of a

doctoral nursing program online orientation. Nursing Education Perspectives,

37(6), 343-4. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nep.0000000000000053

*Whitehair, K. J. (2010). Reaching part-time distance students in

diverse environments. Journal of Library & Information Services in

Distance Learning, 4(3), 96-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2010.503166

*Whiting, P. & Orr, P. (2013). Evaluating library support for a new

graduate program: Finding harmony with a mixed methods approach. The Serials

Librarian, 64(1-4), 88-98. https://doi.org/10.1080/0361526X.2013.760329

*Wills, C. E., Stommel, M. & Simmons, M. (2001). Implementing a

completely web-based nursing research course: Instructional design, process,

and evaluation considerations. Journal of Nursing Education, 40(8),

359-362. https://doi.org/10.3928/0148-4834-20011101-07

*Wimmer, E., Morrow, A., & Weber, A. (2014). Collaboration in

eTextbook publishing: A case study. Collabrative Librarianship, 6(2),

82-86.

.

Appendix A

Search Strategies

Initial searches were

completed on July 30, 2019. Bridge searches were run on December 7, 2021.

CINAHL; Medline; ERIC;

Library Literature & Information Science Index (H.W. Wilson); and Library,

Information Science & Technology Abstracts

(Graduate nursing students

OR students, nursing, graduate OR students, nursing doctoral OR students,

nursing, Masters OR education, nursing, graduate OR MSN OR DNP OR ((masters OR

PhD OR doctoral OR graduate student*) AND nurs*)) AND (Library orientation OR

library user education OR library instruction OR ((Librar* OR information

literacy) AND (instruction OR workshop OR orientation OR session OR class)))

Search notes:

Subject headings and

keywords associated with the two concepts of graduate nursing students and library

instruction were included in the search (see Table A1 for list of included

subject headings). Medline, CINAHL,

ERIC, and PsycINFO were searched concurrently through the EBSCO Interface.

While it is possible to use field codes to restrict search terms to specific

fields, a more comprehensive search is possible with the “Select a Field”

option. When using “Select a Field” all search terms are searched in the

author, subject, keyword, title, and abstract fields which reduces the chance

of missing relevant results. More information about using the “Select a Field”

option can be found here: https://help.ebsco.com/interfaces/EBSCO_Guides/General_Product_FAQs/fields_searched_using_Select_a_Field_drop_down_list).

All searches were limited to

English. The initial search was limited to 1994 through July 2019. The bridge

search was limited to July 2019 through December 2021.

Table A1

Subject Headings for Each

Database

|

|

Concept – Graduate nursing students |

Concept – Library instruction |

|

Database |

Subject headings |

Subject headings |

|

CINAHL |

Students, nursing,

graduate Students, nursing, masters Students, nursing,

doctoral |

Library user education |

|

Medline |

Education, nursing,

graduate |

Libraries |

|

ERIC |

Graduate students Nursing students Doctoral students |

Library instruction |

|

Library Literature &

Information Science Index |

Students |

Library orientation |

|

Library, Information

Science, & Technology Abstracts |

Students |

Library orientation |

Library & Information

Science Abstracts (LISA) (searched

through ProQuest interface):

(Graduate nursing students

OR students, nursing, graduate OR students, nursing doctoral OR students,

nursing, Masters OR education, nursing, graduate OR MSN OR DNP OR ((masters OR

PhD OR doctoral OR graduate student*) AND nurs*)) AND (Library orientation OR

library user education OR library instruction OR ((Librar* OR information

literacy) AND (instruction OR workshop OR orientation OR session OR class)))

Search notes:

All searches were limited to

English. The initial search was limited to 1994 through July 2019. The bridge

search was limited to July 2019 through December 2021.

Google Scholar (first 100 results examined)

(Graduate nursing students |

MSN | DNP | ((masters | PhD | doctoral | graduate student) AND nurse))

((Library OR information literacy) AND (instruction | workshop | orientation |

session| class))

Search notes:

The initial search was

limited to 1994 through 2019. The bridge search was limited to 2019 through

2021.

Appendix B

Sources Included in Scoping

Review

Table B1

Characteristics of Sources

*S/G/T are Standards,

Guidelines, or Theories used to develop instruction.

|

Author(s), Date, Population, Location |

Class

OR Program S/G/T* |

Format (F2F

= face-to-face) |

Timing, Duration |

Content

taught |

Additional

support |

Methodology, Assessment, Other

notes |

|

Bernstein

et al., 2020, DNP

Students, United

States |

Class

- DNP Intro Level Class Essentials

of Doctoral Education for Advanced Practice Nursing |

No

indication of format. |

First

week of class. No

indication of class duration. |

Reading

and evaluating nursing research; database searching focused on advanced

features such as filters. |

Follow-up

research appointments with librarian. |

Survey. Survey

of feelings and attitudes. Instruction

tied to course assignments. |

|

Deberg, 2014, DNP

Students, Iowa |

Two

classes - 1.

Primary Care and Older Adult II 2. Finding Evidence

for Practice. Essentials

of Doctoral Education for Advanced Practice Nurses. |

1.

Hybrid -F2F lecture, recorded for distance students. 2.

Virtual- Online videos of database demos and lectures. |

1.

& 2. No mention of timing or duration. |

Class

1 -structuring clinical questions, evaluating evidence strength, utilizing

clinical and literature databases. Class

2 - Databases demoed, no specifics. |

1.

& 2. Individual meetings via phone, email, or Web. |

Case

report. 1.

& 2. Assessment mentioned but no results provided. 1.

Anecdotal evidence of success from nursing faculty and conversations with

students. Not

clear if F2F lecture in class 1 was delivered by librarian or nursing

faculty. Instruction

was tied to course assignments. |

|

Dorner

et al., 2001, Master’s

students, Indiana |

Both

- Program

was tiered approach in BSN and MSN. Specific

MSN class – NURS

605. No

S/G/T mentioned. |

Virtual

– online tutorials, each with a pre and postquiz, developed for specific

courses and inserted at point of need. |

Module

for NURS 605 was assigned during first two weeks of semester and contained multiple

tutorials. No

mention of duration or number of tutorials. |

NURS

605 - |

Online

discussion boards, online chat sessions for small groups. |

Case

report. Each

tutorial of the module had a pre and postquiz, however no results were provided. Instruction

was tied to course assignments. |

|

Francis

& Fisher, 1995, Master’s

and PhD students, Florida |

Program No

S/G/T mentioned. |

F2F |

No

indication of timing. Two

sessions, each two hours long. |

CINAHL/Medline

(search strategies including limits, controlled vocab |

Additional

content for off-campus users: Using

databases from off-campus. |

Case

report. Mentions

assessment but no results provided. Anecdotal

evidence - librarians reported that nursing students asked fewer basic

questions. Instruction

was tied to course work. Students

were required to participate, assignments were graded, or credit was received

for participation. |

|

Guillot

& Stahr, 2004, Master’s

students, Louisiana |

Class

- NURS

600 Theoretical

Foundations of Advanced Nursing No

S/G/T mentioned. |

Hybrid

- Traditional

bibliographic instruction followed by optional individual virtual sessions. |

No

indication of timing. Session

was 1 hour with 20 minutes spent scheduling individual sessions. Duration of

individual sessions varied. |

Health

science databases, library services, virtual reference. Individual

virtual sessions were tailored to each student with students expected to have

chosen relevant search terms before the meeting. |

Follow-up

email with a transcript of the virtual session. |

Program

evaluation. Focus

was assessment of practicalities of providing the program, no assessment of

instructional effectiveness mentioned. |

|

Guillot

et al., 2010, Master’s

students, Louisiana |

Class

- NURS

500/600 Theoretical

Foundations of Advanced Nursing Information

Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education; Standards

for Distance Learning Library Services. |

Embedded |

Available

throughout semester. Assistance

provided at point of need. |

Content

driven by student questions on discussion board. Questions for the specific

semester included assessing library resources remotely, using interlibrary

loan, APA, and help with research questions. |

Broadcast

email about how to access assigned articles. |

Case

report. Anecdotal

evidence that students were enthusiastic about the service (derived from

course evaluations). Librarian

embedded into course management system. |

|

Hinegardner

& Lansing, 1994, Master’s Students, Maryland |

Class

- Computer

Applications in Nursing and Health Care No

S/G/T mentioned. |

F2F |

No

indication of timing. 3-hour

session. |

Computerized

literature searching, databases, search strategy development, file management

software. |

None

mentioned. |

Case

report. No

assessment mentioned. Focus

of article is development of Nursing Informatics program. Instruction

tied to class assignment. |

|

Hodson-Carlton

& Dorner, 1999 Master’s

students, Indiana |

Class

- NUR

605 No

S/G/T mentioned. |

Virtual

- Interactive

Web instructional module. |

Module

took place in the 3rd or 4th week of the semester. No

indication of duration of module. |

Evaluation

of Web resources using seven evaluation criteria (scope, audience, authority,

currency, accuracy, purpose, and organization). |

One

synchronous chat session; asynchronous online bulletin board which included

both a nursing faculty member and a librarian. |

Quasi-experimental.

Pre-post

quiz with six true/false questions about Web information. Open-ended

questions about perceptions also included in postquiz. Instruction

tied to class assignments. |

|

Honey

et al., 2006, Master’s

students, New

Zealand |

Program Australian

& New Zealand Information Literacy Framework |

Hybrid

- F2F

plus online tutorials and Web-based resource pages. |

F2F

orientation beginning of semester. No

indication of duration. Course

related sessions provided within classes. |

F2F

orientation - nursing specific resources, library tutorials, workshops,

librarian contact info. Voluntary

F2F sessions - catalogue, nursing-specific databases including CINAHL,

e-journals. |

Informational

brochure about library resources for nursing students. Small

F2F voluntary sessions. |

Mixed

methods (student surveys plus library staff interviews). Assessment

of library use but no mention of assessment of instructional effectiveness. Focus

of the study is a survey of use of technology by nursing students and changes

made as a result. |

|

Layton

& Hahn, 1995, Master’s

and PhD students, Maryland |

Both

- Program and two classes; MSN

class - Computer Technologies in Nursing. PhD

class - Technology Applications in Nursing Research. No

S/G/T mentioned. |

Both

classes F2F |

MSN

Class 2)

two-hour sessions. No

indication of timing. PhD

class two

sessions. No

indication of timing or duration. |

MSN

Class - Internet, email, databases, search strategies, controlled vocab,

Medline, CINAHL, PsycINFO, library services. |

None

mentioned. |

Case

report. Assessment

mentioned but no results provided. All

instructional sessions include lecture, demo, and hands-on training with

students performing exercises on the computer. |

|

Leasure

et al., 2009, Graduate

students (level not specified), Oklahoma |

Both

- Program and

two graduate nursing classes. No

S/G/T mentioned. |

Hybrid

- Both

F2F and online tutorials. |

Early

Graduate Nursing Class No

indication of timing or duration of F2F instruction. Graduate

Research Course No

indication of timing or duration. |

Early

Course - Online

tutorial – webpage evaluation. Research

Course – |

Additional

free training sessions were available to individuals wishing to improve their

skills. |

Case

report. No

assessment mentioned. Instructional

sessions consisted of lecture plus live demo searches followed by discussion

among students, librarian, and nursing faculty member. |

|

Lemley,

2016, Master’s

and DNP Students, Alabama |

Program No

S/G/T mentioned (did reference best practices for embedded librarians). |

Embedded |

Available

throughout semester. Assistance

provided at point of need. |

Driven

by questions. Individual questions answered include APA, definitions of

research types, where to search, CINAHL. |

Encouraged

to contact the librarian by phone, email, or discussion board. Online

videos and tutorials for specific databases and ILL. |

Case

report. No

assessment mentioned. Librarian

listed as instructor in course management system. |

|

Milstead

& Nelson, 1998, PhD

students, Pennsylvania |

Both

- Program

and Nursing PhD course -Politics and Health Policy Development. No

S/G/T mentioned. |

Virtual (webpage) |

Webpage

available throughout the course. |

Frequently

used library functions/resources. |

Vendor

rep provided instruction for class on Westlaw database. |

Case

report. Mentioned

assessment of library use and access, but no results provided. No assessment

of instructional effectiveness mentioned. Primary

focus is development of program, limited discussion of library involvement,

no librarian author on article. |

|

Schilperoort, 2020, Master’s

students, California |

Two

clinical classes (no specifics on class name). Andragogy,

Constructivist learning theory |

Virtual

asynchronous interactive video tutorial. |

Embedded

in LMS. Self-paced,

estimated 15 to 30 minutes to complete tutorial. |

Identifying

level of evidence and locating library resources to find evidence. |

None

mentioned. |

Quasi-experimental. Pre-post

tests, Survey of confidence with some open-ended questions. Unique

focus on clinical courses. Tutorial

was required; assignment was graded credit or no-credit. |

|

Thompson, 2009, Master’s

students, Canada |

Class

– Research

Methods Course No

S/G/T mentioned. |

F2F |

No

indication of timing of class. Compared

two iterations with differing durations. First

iteration was 1) 3-hour class, second iteration was 3) 3-hour classes. |

1st

iteration (3 hr. class) – lecture on basic concepts of data &

quantitative research, demo of basic analysis in SPSS, hands-on practice with

provided dataset. |

Assistance

at the academic data center on a walk-in basis. |

Survey

(students’ feelings/ attitudes). 1st

iteration – anecdotal evidence (Instructor reported high grades on

assignment). 2nd

iteration – student survey. Instruction

tied to class assignment.

|

|

Welch

et al., 2016, PhD

students, Georgia |

Program

-Orientation No

S/G/T mentioned. |

Virtual (online

interactive modules). |

Access

before classes began, but not clear if modules had to be completed before

classes began. No

indication of duration of modules. |

4

modules - topics included scholarly writing, APA, library databases, lit

reviews, research questions/ hypotheses, popular vs. scholarly, theoretical

frameworks, Endnote, planning a research study, research ethics. |

None

mentioned |

Case

report. Reports

meeting as a group to discuss orientation assessments and evaluations but no results

provided. Describes

shift to online modules for student support. |

|

Whitehair,

2010, Master’s,

DNP, and PhD students, Kansas |

Both

- Program

and two classes - DNP

capstone course PhD

on-site sessions. Practice

Doctorate Nurse Practitioner Entry-Level Competencies; Kuhlthau’s Model of

the Information Search Process; Kraft

and Androwich’s student-centered model. |

Hybrid

- F2F,

synchronous online instruction, videos. |

Orientation

preclass. DNP

course - beginning of semester, recorded; No indication of duration. Q&A

session several weeks later. PhD

students – 1st & 3rd

week included 1-hr library sessions; 2nd week individual meetings. |

Orientations

- critical resources, off-site access. DNP

Capstone Course - lit searching, video tutorials, resources. PhD

sessions -1. library services, website, databases, 2. - voluntary

meetings. 3. complex searching, refining searches, current awareness

services. |

One-on-one

interaction with library liaisons was encouraged and available in person, via

phone, online conferencing, and instant messaging. |

Case

report. No

assessment mentioned. SON

faculty encouraged to add library contact info to the syllabus and to set up

"Ask a Librarian" discussion boards in all courses. |

|

Whiting

& Orr, 2013, DNP

students, Indiana |

Both

- Program, Orientation No

S/G/T mentioned. |

No

indication of format of orientation. |

No

indication of timing or duration of orientation. |

Content

that changed as a result of the research – improved explanation of ILL and

document delivery, more time spent on citing and citation resources, greater

emphasis on nine nursing journals added to the collection in support of the

new DNP program. |

Librarians

maintained a "library support" section within the general

Blackboard site. |

Mixed

methods. Analysis

of research paper reference lists and survey

of library resources/services satisfaction but no assessment of instructional

effectiveness mentioned. Focus

is support of DNP program over three years rather than instruction. |

|

Wills

et al., 2001, Master’s

students, Michigan |

Class

- Nursing

811 Concepts

of Research and Evaluation for Advanced Practice Nurses No

S/G/T mentioned. |

Embedded |

Available

throughout semester. |

CINAHL,

Medline, ProQuest Direct, and other health-science databases. |

Individual

consultations via email or F2F. Discussion room in WebTalk for questions and

where the librarian posted content. |

Case

report. There

was an end-of-class evaluation, but no assessment of library support was

reported. Focus

is the development of an online nursing class in the Master’s program,

including info about library support. |

|

Wimmer

et al., 2014, PhD

students, Utah |

Class

- Research

with Diverse Populations No

S/G/T mentioned. |

Virtual

-synchronous |

Second

week of class was an orientation to library resources with question-and-answer

session. No

indication of duration. |

No

information beyond that it was an orientation to library resources. Librarian

assisted with full-text, remote access, and ILL. |

Research

guide for Evidence-Based Nursing shared via course management system. |

Case

report. No

assessment mentioned. Focus

is describing librarians' involvement in the creation of an e-textbook by

students in the class. |