Research Article

A Mismatched Group of Items That

I Would Not Find Particularly Interesting: Challenges and Opportunities with

Digital Exhibits and Collections Labels

Melissa Harden

Product Owner, Center for Research Computing

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame, Indiana, United States of America

Email: mharden@nd.edu

Anna Michelle Martinez-Montavon

Online Education and Technology Consultant

Indiana University South Bend

South Bend, Indiana, United

States of America

Email: ama9@iu.edu

Mikala Narlock

Director, Data Curation Network

University of Minnesota

Minneapolis, Minnesota,

United States of America

Email: mnarlock@umn.edu

Received: 21 June 2022 Accepted: 18 Oct. 2022

![]() 2022 Harden, Martinez-Montavon, and Narlock. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2022 Harden, Martinez-Montavon, and Narlock. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30194

Abstract

Objective – The authors sought to identify link language that is

user-friendly and sufficiently disambiguates between a digital collection and digital

exhibit platform for users from a R1 institution, or a university with high

research activity and doctoral programs as classified in the Carnegie

Classification of Institutions of Higher Education.

Methods – The authors distributed two online surveys using a

modified open card sort and reverse-category test via university electronic

mailing lists to undergraduate and graduate students to learn what language

they would use to identify groups of items and to test their understanding of

link labels that point to digitized cultural heritage items.

Results – Our study uncovered that the link terms utilized by

cultural heritage institutions are not uniformly understood by our users. Terms

that are frequently used interchangeably (i.e., Digital Collections, Digital

Project, and Digital Exhibit) can be too generic to be meaningful for different

user groups.

Conclusion – Because the link terms utilized by

cultural heritage institutions were not uniformly understood by our users, the most user-friendly way to link to these resources is to

use the term we—librarians, curators, and archivists—think is most accurate as

the link text based on our professional knowledge and provide a brief

description of what each site contains in order to

provide necessary context.

Introduction

The main library website serves as a prominent access point for the entire

enterprise of library resources, including print and online materials,

services, and spaces. As Polger (2011) described

“[t]he library website is a living document” (para. 1), changing as new

information, resources, services, or features are made available. Because a

library website makes a wide range of information available to users, it is

imperative that the resources linked from the site are labeled, described, and

contextualized in a meaningful way. In order to allow

users to make informed decisions about which links are relevant to their needs,

link labels must make sense.

At the time this study was conducted, there was a link in the main

navigation of our library’s website labeled “Digital Collections,'' which

pointed to a platform that included digital exhibits from our rare books

department entitled “Digital Exhibits and Collections.” At the same time, we

were about to launch a new site called “Marble,” a platform for providing

access to digitized cultural heritage materials from our campus art museum,

university archives, and rare books departments. We needed to determine an

appropriate link label for this new site that succinctly and appropriately

described it without introducing confusion. The digital exhibit platform

primarily featured digital exhibits—interactive sites that feature curatorial

text and collection highlights—while the new site primarily featured digital

collections– akin to a catalog of items that are made available with basic

descriptive data. This marked the first time our library had two separate

platforms for these two distinct use cases. As a result, the name of the

original platform, Digital Exhibits and Collections, would no longer be

accurate because the two functions were split into two different sites, with

collections moved to Marble. Therefore, we needed to identify link labels for both of these sites that accurately, meaningfully, and

concisely described and differentiated the two resources in a way that made

sense to users. We also wanted to ensure that any link language

leveraged would be useful and understandable to both novice and advanced users,

as our campus population includes undergraduate and graduate students,

postdoctoral scholars, and faculty members from a wide variety of disciplines.

The need to add

a link to the new digital collections site in the library website’s main

navigation provided an opportunity to learn what link labels users thought best

described the types of specialized resources found on the digital exhibits platform and digitized collections site. In our

local context, because one site primarily featured digital collections and the

other platform primarily featured digital exhibits, we needed to find out what

meaning, if any, the term “digital exhibits” had for our users to determine if

this would be a useful link label. We sought to test language that would

resonate with users and strike a balance between the overly general and overly

specific.

We first

conducted an environmental scan of Association of Research Library (ARL)

websites to see if there was consistent link label language used by our peer

libraries for digital exhibits and digital collections links. Finding none, we

looked to the literature to see if other studies had been conducted for this

purpose. Because no study was identified that tested these specific terms (i.e.,

“Digital Collections” and “Digital Exhibits”) against each other, we determined

that we needed to design our own study for this purpose. Therefore, we designed

a user study to help us answer the question, “What meaningful, user-centered,

and concise link language accurately describes and differentiates between two

sites?” Specifically, we were interested in testing how well the terms “digital

collections” and “digital exhibits” resonated with users, including both

undergraduate and graduate students. The intention of this dual audience was to

see if there was a difference between novice and advanced users. Given that the

library website is the main portal for the entire student body, we wanted to be

sure that any link language used would be understandable for all.

Literature Review

For the purposes of this research, we focused on the published articles and

presentations on user experience testing that focus on link labels (or link

language) and card sorting activities. This selected literature review provided

a solid grounding in the theories and best practices of both to ensure we were

not duplicating research efforts and allowed us to build on previous work so we

could be thoughtful and intentional in how we designed our surveys. Because our

study falls at the intersection of link labels and card sorting exercises, we

have divided our literature review into these two categories below.

Link Labels

Link labels are

the words or phrases that display a hyperlink. It is important that link titles contain meaningful natural language but

are also specific enough to give a clear impression of where those links point.

There are several factors users consider when

determining whether or not to click on a link, one of which is the link label (Budiu, 2020). Through various studies, it

is clear that using terminology that is too broad to be helpful has been

identified as an issue in library card sorts (Duncan & Holliday, 2008;

Hennig, 2001; Lewis & Hepburn, 2010). Alternatively, using very specific

language may cause link text to be too long (Dickstein & Mills, 2000),

leading to visual clutter. While there may be some variation in findings based

on individual library context, one common theme is that links with branded

names are unlikely to be interpreted correctly by users (Gillis, 2017; Hepburn

& Lewis, 2008; Kupersmith, 2012). Based on this

information, we did not consider using the branded names—the institutionally-specific name used to market and promote a resource

or service—of our digital exhibits platform

and collections site as potential link labels on the main library website and

sought to test language that would resonate with users and strike a balance

between the overly general and overly specific.

A user-centered approach means using website language that resonates with

users; however, as Francoeur (2021b) pointed out, it can be challenging “to

balance the demands to be concise, clear, and understandable” (para. 2). This

is especially true when library- or archives-specific language or jargon is

used (Burns et al., 2019). The terms used to describe materials by information

professionals have distinct meanings: reducing them to common terms is not only

a disservice to our profession and unique skill set, but also to our users, as

overly generic terms can be equally confusing. Moreover, leveraging the

appropriate term can serve as an educational opportunity, teaching even casual

browsers of content the nuances between terms, leading to more efficient searching

and use of materials in the future. Burns et al. (2019), described the

importance of the challenge accurately: “More than just an issue of semantics,

the branding and labeling we employ in digital library interfaces plays a

critical role in helping users find, utilize, and understand archival and

special collections in the online environment” (p. 5).

The study Burns et al. (2019) conducted presented the closest match to the

information we wanted to discern in our own case. In this study, the researchers

reviewed terminology used by ARL member libraries to identify which terms were most commonly used to label digitized cultural heritage

collections. They identified a variety of terms, noting that the inconsistent

use of terms may be confusing to users. Burns et al. designed a survey-based

study to identify the terminology that users were “most likely to associate

with different materials commonly found in digital libraries” (p. 5) and the

terms that “are potentially confusing and likely to be misunderstood by users”

(p. 6). Their task-based questions asked users where they would click to find

various items that typically appear in digital libraries and were meant to help

identify terminology that would disambiguate the term “digital library.” The label

options provided to respondents included Digital History Collections, Digital

Library, Digital Archives, and Digital Collections (Burns et al., 2019, p. 7).

Their results suggested that there is little to no consensus about the

interpretation of these various labels, highlighting the challenge that exists

in meeting various web usability goals with respect to link labels and

terminology.

While the study conducted by Burns et al. (2019) addressed a very similar

question to ours and provided a useful framework for the design of our study,

theirs did not test or address the use of “digital exhibit” as a link or

navigation label. Similarly, there was no mention of best terms for digital

collections and digital exhibits in the document “Library Terms That Users

Understand” (Kupersmith, 2012). In our local context,

because one site primarily features digital collections and the other platform

primarily features digital exhibits, we needed to find out what meaning, if

any, the term “digital exhibits” has for our users to determine if this would

be a useful link label. A deeper dive into the relevant literature indicated

that the term “digital exhibits” has not been adequately studied from a

user-experience perspective. When studying digital libraries, the researchers

in usability studies have tended to focus on terms like “digital library” or

“digital archive” without much analysis as to why those were the terms selected

(e.g., Burns et al., 2019; Kelly, 2014). Instead, terms like “digital

collections” and “digital exhibits” can be, and often are, used interchangeably

in library literature without much analysis. In some instances, the words are

used synonymously, e.g., the book Digital

Collections and Exhibits is exclusively about exhibits, yet the author

published under both terms (Denzer, 2015).

For the purposes

of this research, we defined digital collections as a catalog of items

that are made available with basic descriptive data, and users search and sort

as they wish; digital exhibits, on the other hand, are highly mediated online

experiences that feature specially selected items, extensive curatorial text,

and often a predetermined path to explore the content.

Card Sorting

Card sorting has been used by several libraries to test site structure and nomenclature, and is in fact a frequent testing option for

libraries (Brucker, 2010). A key benefit of card sorting is that users can

propose their own organizational and mental models for information and are not

influenced by pre-existing structure (Faiks &

Hyland, 2000). There are numerous variants of the card sorting exercise, all of

which are used for different purposes (Spencer, 2009). For example, some

studies leveraged an open card sorting activity, which allowed testing

participants to sort cards into categories they create (e.g., Dickstein &

Mills, 2000; Lewis & Hepburn, 2010; Robbins et al., 2007; Sundt &

Eastman, 2019; Whang, 2008). Others have used closed card sorting tests, in

which users were provided categories and asked to put content into the

pre-defined groupings (e.g., Diller & Campbell, 1999; Faiks

& Hyland, 2000; Guay et al., 2019; Hennig, 2001;

Paladino et al., 2017; Rowley & Scardellato,

2005). Others have used a hybrid approach (e.g., Paladino et al., 2017), in

which participants could sort into predefined groups or create their own.

Lastly, while card sorting is commonly used for in-person user experience

testing, it has also been leveraged remotely (e.g., Ford, 2013).

Reverse category tests have been used by some academic library teams to

validate or expand upon results from prior card sorting activities in

preparation for larger website redesign projects (Hennig, 2001; Sundt &

Eastman 2019; Whang, 2008). In these cases, users were asked where they would

click to find specific items, resources, types of information, and others, and

were provided different categories as answer options. These categories

corresponded with main navigation categories.

Aims

In order to determine a

concise, specific, and non-duplicative term to label the newly launching

digital library platform, Marble, and relabel the existing digital exhibits

platform, Digital Exhibits and Collections, the authors set out to answer the

question: which link terms do our users not only understand, but also find

meaningful? How can we, as librarians and information professionals,

sufficiently differentiate between terms like “Digital Collections” and

“Digital Exhibits”— terms that are often used interchangeably but have specific

meanings?

Method

To address this challenge, our team developed a multi-phased, institutional

review board (IRB) approved study that was conducted in

Spring 2021, when the authors all worked at Hesburgh Libraries, University of

Notre Dame. First, with the help of student workers, we conducted an

initial review of different link titles used on the websites of ARL member

libraries. This work was critical to confirm that there was no consensus on or

consistency in application of various terms, as well as to identify potential

terms to test in parts two and three of our study. Secondly, we developed an

initial survey that was a modified open card sort—we provided users with items

already sorted into groups and asked them to supply labels for the groups. Thirdly,

using the terms provided from the first survey, as well as from the ARL

members’ websites, we developed a second survey, a reverse category test, in

which users were asked to identify which items or features they would expect to

find based on various link terms. Data was analyzed to identify patterns and

themes, and ultimately to inform decisions about link language on the main

library website. This section provides more details on our methods and

decisions.

ARL Link Language Environmental Scan

We chose to focus the initial scan on ARL libraries because they are part

of our peer network; many of these libraries dedicated similar time and

resources to their digital collections and exhibits. We recruited student

workers to browse the websites of all 148 ARL libraries and record any link

related to digital exhibits or online collections on the home page or main

navigation; anything that was online and could be even tangentially related was

captured, including terms such as “digital library” and “digital resources.”

For sites that leveraged explanatory language to clarify their links (e.g.,

“This site is for X, Y, Z”) the title of the link, as well as the additional

contextual information, was captured for a holistic view of how these libraries

presented their digital collections. While we did capture a few sites with

branded names, we did not include those in our analysis, as those would be too

specific to the institution and not helpful for our purposes.

User Surveys

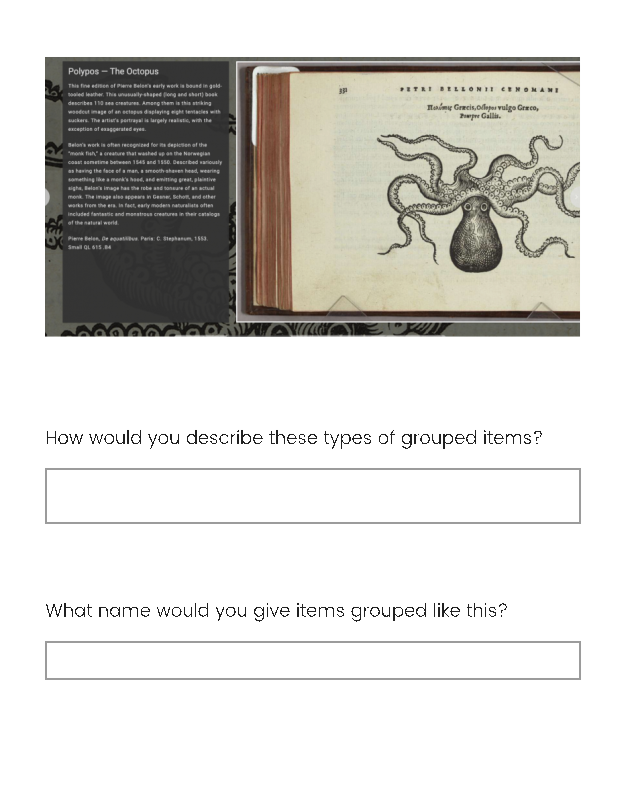

Modified Open Card Sort

As a follow-up

to our environmental scan of ARL libraries, we conducted two surveys of Notre

Dame students. The first survey was designed to operate like a modified open

card sort—we provided users with items already sorted into groups and asked

them to supply labels for the groups (see Appendix A for full survey). It was

critical that the questions on the survey did not include the language we were

testing so as to not predispose our users to the

language we expected (Nielsen, 2009). The first group of items contained

screenshots of items and descriptions from the digital collections

platform, and the second group of items contained screenshots from portions of

digital exhibits. All screenshots were cropped to remove any site branding or

logos. For both groups of items, we asked users two open-ended questions: “How

would you describe this group of items?” and “What name would you give a group

of items like this?” Both of these questions were

designed to better understand how users interpret these items and elicit

potential terminology, without suggesting common library terms, like

“collections” or “exhibits.” While the second question directly asked

respondents to provide a group label, the first one was purposefully meant to

elicit longer responses, with the aim of understanding users’ thinking and

collecting additional link label terms to test in the second survey. We did not

use a formal coding method to analyze the survey results but rather noted the

frequency of the terminology supplied by our users for the link labels as well

as in the free-text descriptions of content. We focused on identifying unique

terms that were used most often, as well as less-used terms that might appear

on library websites.

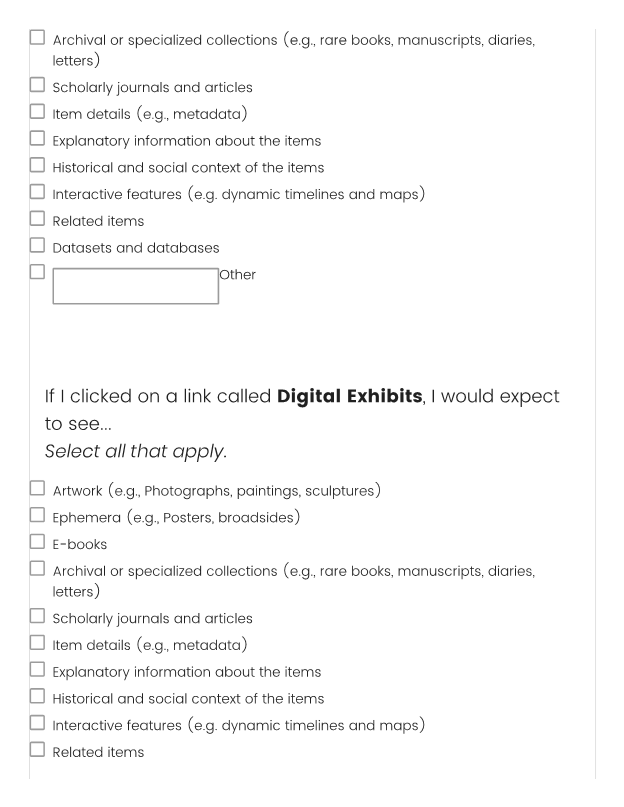

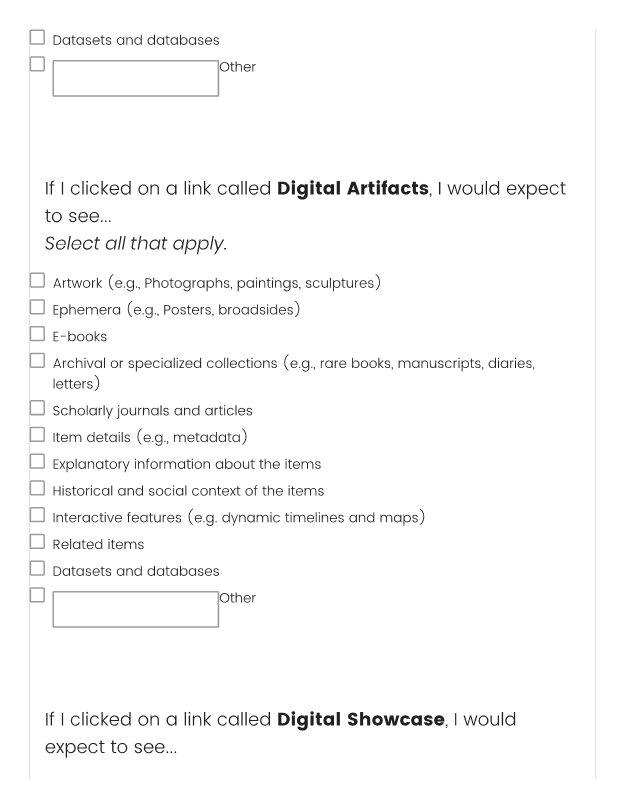

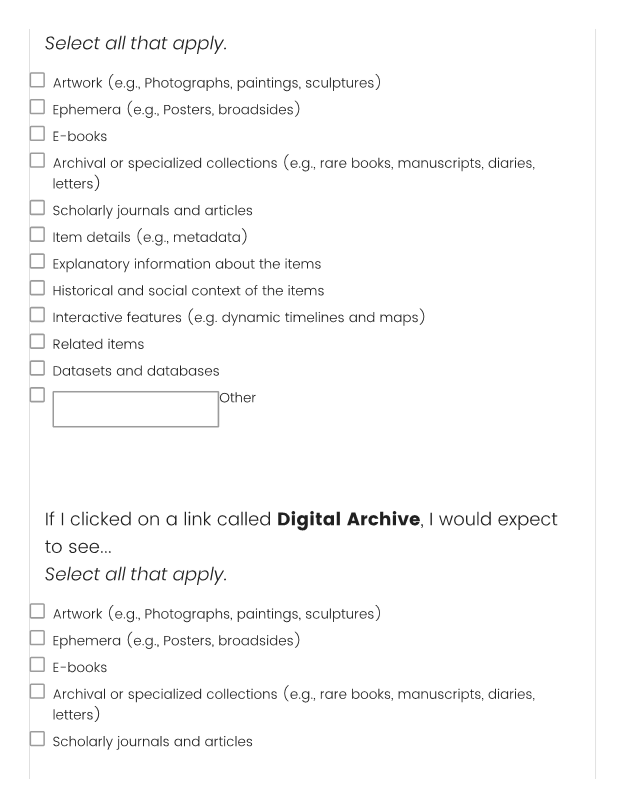

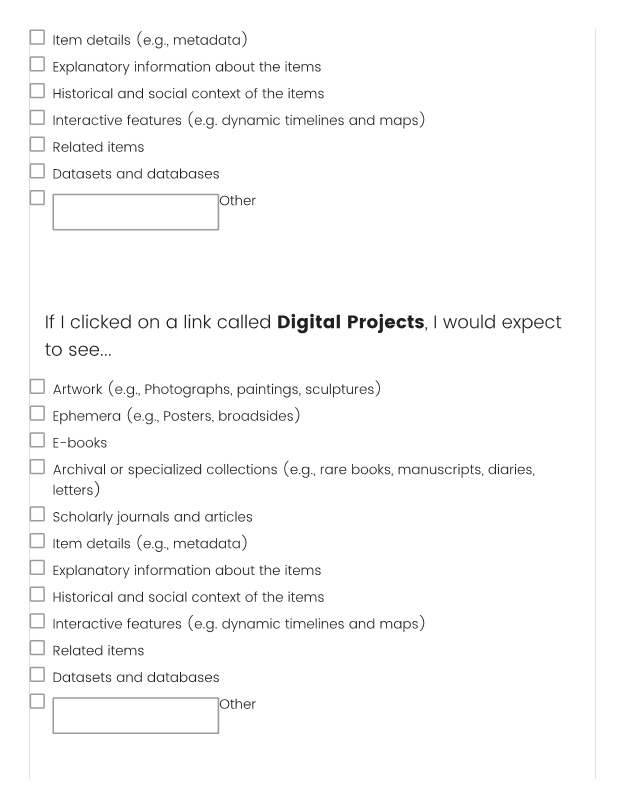

Reverse Category Test

The second user

survey was designed to operate like a reverse category test, much like the one

described in the Burns et al. (2019) study. The key difference between their

study and ours is our inclusion of digital exhibits in the test. The first set

of six questions asked students, “If I clicked on a link called [link label], I

would expect to see…” where the link label was changed to test different words

or phrases. The link labels tested were: “Digital Collections,” “Digital

Exhibits,” “Digital Artifacts,” “Digital Showcase,” “Digital Archive,” “Digital

Projects,” and “other” where students could provide their own text. We chose

these labels based on our own local context (“Digital Collections” and “Digital

Exhibits” have meanings and scopes that are well understood in our own library

system), the student responses from the first survey (“Digital Artifacts” and

“Digital Showcase”), and our analysis of ARL library websites (“Digital

Archive” and “Digital Projects”).

For each link

label, respondents were asked to select all answer options that applied. Answer

options included: artwork (e.g., photographs, paintings, sculptures), ephemera

(e.g., posters, broadsides), e-books, archival or specialized collections

(e.g., rare books, manuscripts, diaries, letters), scholarly journals and articles,

item details (e.g., metadata), explanatory information about the items,

historical and social context of the items, interactive features (e.g., dynamic

timelines and maps), related items, datasets and databases, and other (with a

write-in option). Some of these answer options were included based on student

responses from the first survey, and some of them were supplied by the authors.

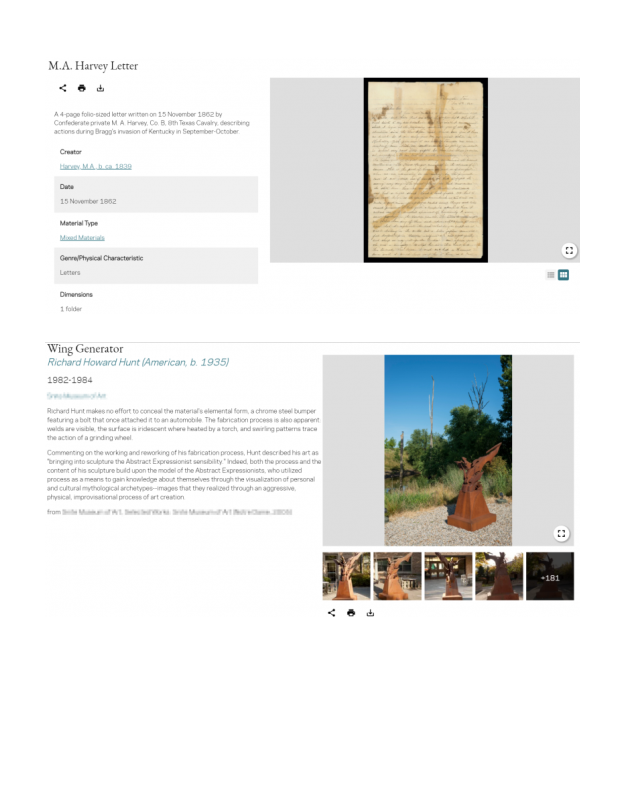

The second set

of questions on the second survey asked: “Below are examples of content linked

from a library website. What link would you follow to get to each item?” The

examples contained screenshots of digitized items from our digital collections

and digital exhibit platforms, plus descriptive text

and metadata (see Appendix A for full survey). In order to

minimize the visual differences between the way that items in these two

platforms are presented, we used screenshots of just the item image and cut and

pasted the exhibit text or collection metadata into the survey platform so that

the formatting from the different sites would not influence student answers.

The answer options were the same as the labels for the first part of the survey

(“Digital Collections,” “Digital Exhibits,” “Digital Artifacts,” “Digital

Showcase,” “Digital Archive,” and “Digital Projects” along with an “Other”

write-in option). Students were only able to select one of these choices.

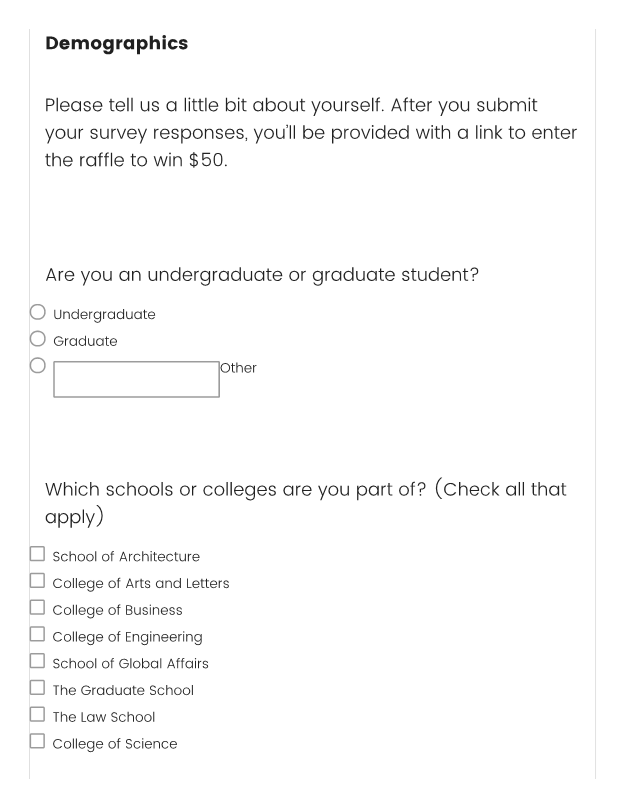

These surveys

were distributed online through two key mechanisms: the university-wide weekly

update, which reaches all undergraduate and graduate students, and electronic

mailing lists of different disciplines, including political science and art

history, which reach more targeted groups of undergraduates and graduate

students. The goal with using the university-wide email was to reach and

solicit input from users that might rarely leverage online cultural heritage

materials, such as students from disciplines like business, engineering, or

psychology. We chose the political science and art history specific electronic

mailing lists because we assumed these students would be familiar with online

cultural heritage materials and might represent our more advanced users. By

approaching the survey distribution from this perspective, we hoped to

represent both novice and advanced users.

For both

surveys, students who completed the survey were entered into a chance to win a

$50 gift card; for the first survey, one gift card was offered, and for the

second, three $50 cards were offered. These incentives were funded as part of a

grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Contact information was collected

separately from the survey instrument via a Google Form to keep responses

anonymous.

We reviewed

results from the second survey to determine if there were consistent patterns

among responses that might suggest link labels and terminology that were

commonly understood across user groups.

Results

ARL Link Language Environmental Scan

Unsurprisingly, we found most institutions used terms

like digital collections, digital archives, and digital library; however, those

phrases were not necessarily applied consistently across institutions. For

example, link labels of “Digital Collections” on two different library sites

did not necessarily point to the same types of resources. Some of these digital

collections brought together curated, digitized resources from the library’s

archives and special collections, while others also included scholarship from

university researchers or journals published by the library or university. We

found that links related to digital collections were often located alongside or

underneath headings such as “Collections” or “Specialized Collections.” For

libraries that provided access to and publicized online exhibits, these were

more frequently discoverable alongside digital scholarship projects or events

as a companion to physical exhibits.

With no clear consensus on link labels found through the literature or our

environmental scan, we decided to conduct two user surveys to learn more about

how our students understand the terminology relevant to our question. While

there are numerous ways to evaluate digital libraries, we needed to find

solutions that would more closely match our circumstances. As has been

demonstrated over the past few decades, because “digital libraries are designed

for specific users and to provide support for specific activities… [they]

should be evaluated in the context of their target users and specific

applications and contexts” (Chowdhury et al., 2006, p. 671. For that reason, we

chose to focus on the needs of our students and test them directly through

online surveys.

User Surveys

Modified Open Card Sort

In the first survey, 52 participants started the survey. Twenty individuals

did not complete the survey, and incomplete answers, including partials, were

removed from the dataset for analysis. One respondent who started the survey

noted that these items were “a mismatched group of items that I would not find

particularly interesting,” and did not complete the survey. This left a total

of 32 responses. Respondents were evenly split between graduate and

undergraduate students (n=16). Notre Dame has 8,874 undergraduate

students and 3,935 graduate students (University of Notre Dame, 2022), so our

sample represents a heavier skew toward graduate students than the general

student body. Respondents skewed heavily towards College of Arts and

Letters students (n=32), though this makes sense because the College of Arts

and Letters is the largest college on campus, with 3,000 undergraduate and

1,100 graduate students. The next largest college is the Mendoza College of

Business, with 1,700 undergraduate and 625 graduate students (Mendoza College

of Business, 2022), for about 18% of the student body. In contrast, the School

of Architecture, the smallest school, only awarded 1.6% of all the degrees

conferred at Notre Dame between July 1, 2020, and June 30, 2021 (Office of Strategic

Planning & Institutional Research, 2022). Some students listed multiple

affiliations, e.g., College of Arts and Letters and College of Science, which

is why the total adds up to more than the 32 participants.

Due to the open-ended nature of the survey questions, students’ answers

varied wildly. When asked what term they would give to a group of items

librarians might refer to as digital collections, many used terms like

Historical (n=10, 31%), Art (n=7, 22%) and Artifacts (n=6, 19%). One user also

wondered why these items would be grouped together in one space.

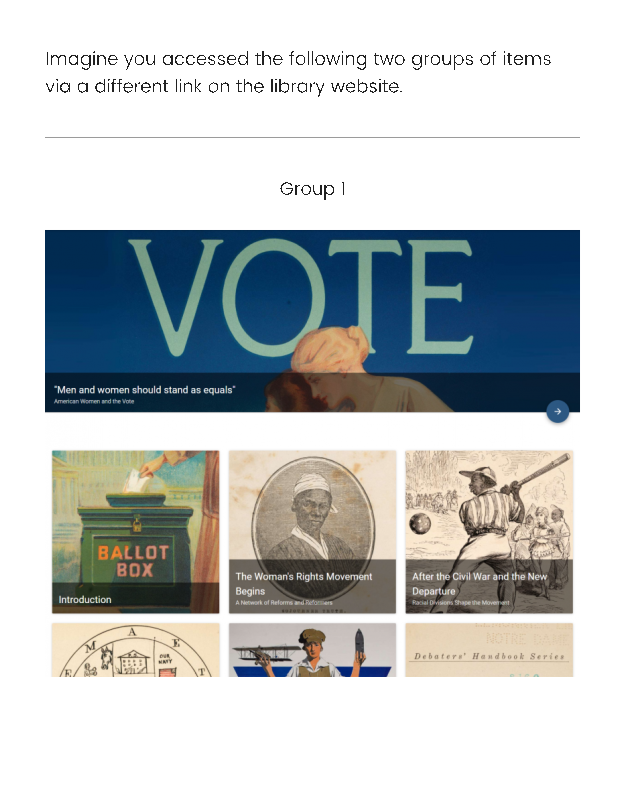

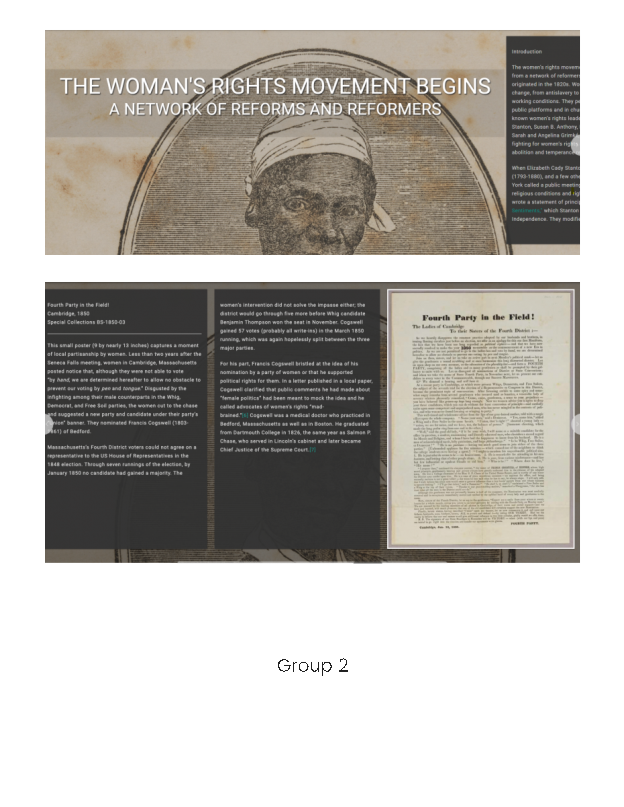

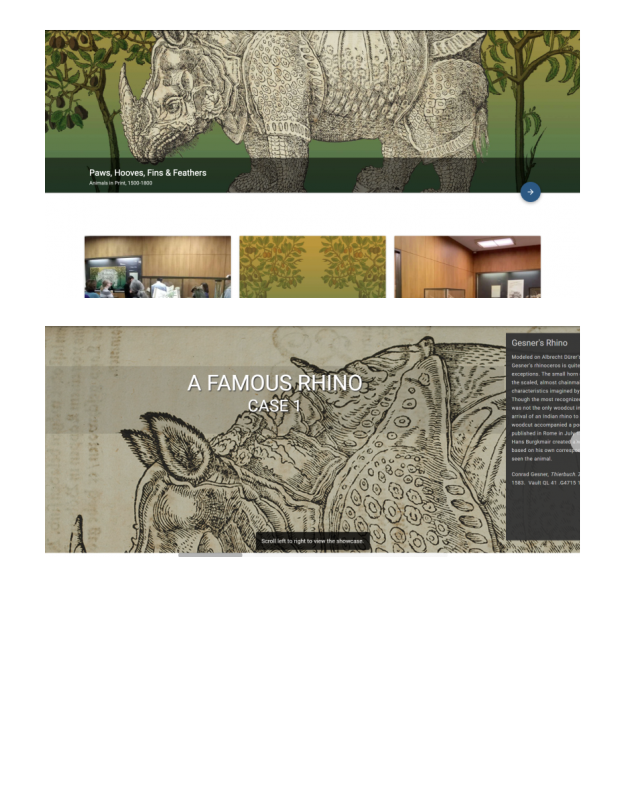

When asked to assign a term to what librarians might call a digital

exhibit, students often focused on the content of the exhibit instead of the

media. We had selected two extant exhibits from our platform: one about women’s

right to vote, and one about printed representations of animals. As a result,

many students used terms like “Socio Political” or “Drawings” to describe the

two. Others were again wondering why these items would be grouped together. At

least three respondents suggested a variation of “collections” and two

suggested “exhibit” or “exhibition.” Based on

students’ responses to this survey, we identified two terms of interest to

test: digital artifacts, because of the frequency in which it showed up in

answers to the first set of questions, and digital showcase, because it seemed

to capture the respondents’ focus on “art” in both sets of questions.

Table 1

First Survey

Respondents by School or College

|

School/College |

Count |

|

School of Architecture |

0 |

|

College of Arts and Letters |

21 |

|

Mendoza College of Business |

5 |

|

College of Engineering |

2 |

|

Keough School of Global

Affairs |

2 |

|

The Graduate School |

4 |

|

The Law School |

0 |

|

College of Science |

5 |

|

Total |

39 |

Reverse Category Test

In the second survey, 45 participants started the survey and 3 did not

complete it. We once again removed all incomplete answers from the dataset for

analysis. Of the 42 participants who completed the survey, 31 were

undergraduate students, 10 were graduate students, and 1 was a postdoctoral

research assistant. Respondents again skewed heavily towards the College of

Arts and Letters (n=27). Some students listed multiple affiliations, e.g.,

College of Arts and Letters and College of Science, which is why the total adds

up to more than the 42.

Table 2

Second Survey: Respondents by School or College

|

School/College |

Count |

|

School of Architecture |

0 |

|

College of Arts and

Letters |

27 |

|

Mendoza College of

Business |

5 |

|

College of Engineering |

6 |

|

Keough School of Global

Affairs |

2 |

|

The Graduate School |

8 |

|

The Law School |

0 |

|

College of Science |

10 |

|

Total |

58 |

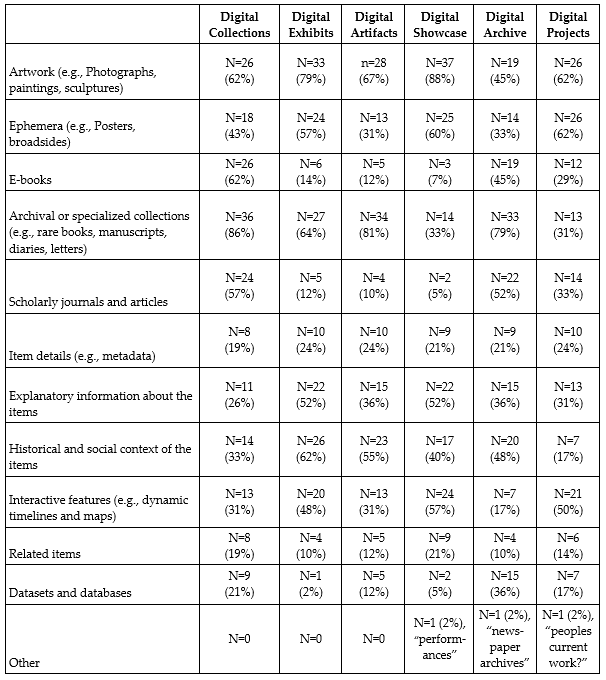

The questions in the second survey were more close-ended, which allowed us to observe some interesting

patterns. When we asked users what they would expect to see in each of the six

potential link labels (Digital Collections, Digital Exhibits, Digital

Artifacts, Digital Showcase, Digital Archive, and Digital Projects), we found

that many expected to find archival or specialized collections in Digital

Collections (n=36), Digital Artifacts (n=34), and Digital Archives (n=33),

while slightly fewer expected to find those materials in Digital Exhibits

(n=27). More than half the students also expected to find e-books (n=26) and scholarly

journals and articles (n=24) in Digital Collections, and a significant number

of students expected to find scholarly journals and articles (n=22) and

datasets and databases (n=15) in Digital Archive.

When it came to features that librarians, archivists, and

curators often associate with our work, student expectations did not always

line up. While a majority of students did expect to

see explanatory information about the items (n=22) and historical and social

context of the items (n=26) in Digital Exhibits, fewer expected to see item

details (e.g., metadata) in any of the link labels (n= between 8 and 10).

There was a wide range of responses to the questions that asked students to

apply labels to specific examples of digitized items. In other words, there was

no identifiable pattern, suggesting that there is not widespread shared meaning

of these terms.

Table 3

Aggregated Responses to the Question “What Would

You Expect to See If You Clicked on the Following Link?”

Table 4

Aggregated Responses from the Second Survey to

the Question, “What Link Would You Click to Get to Each of the Following?”

|

Item Name |

Digital Collections |

Digital Exhibits |

Digital Artifacts |

Digital Showcase |

Digital Archive |

Digital Projects |

Where it lives on our website |

|

Shoes |

N=8 (19%) |

N=24 (57%) |

N=2 (5%) |

N=3 (7%) |

N=4 (10%) |

N=1 (2%) |

Digital Collections |

|

Peru’s First Newspaper |

N=4 (10%) |

N=8 (19%) |

N=17 (40%) |

N=1 (2%) |

N=12 (29%) |

0 |

Digital Exhibits |

|

Collegiate Jazz Festival |

N=8 (19%) |

N=5 (12%) |

N=4 (10%) |

N=5 (12%) |

N=17 (40%) |

N=3 (7%) |

Digital Collections |

|

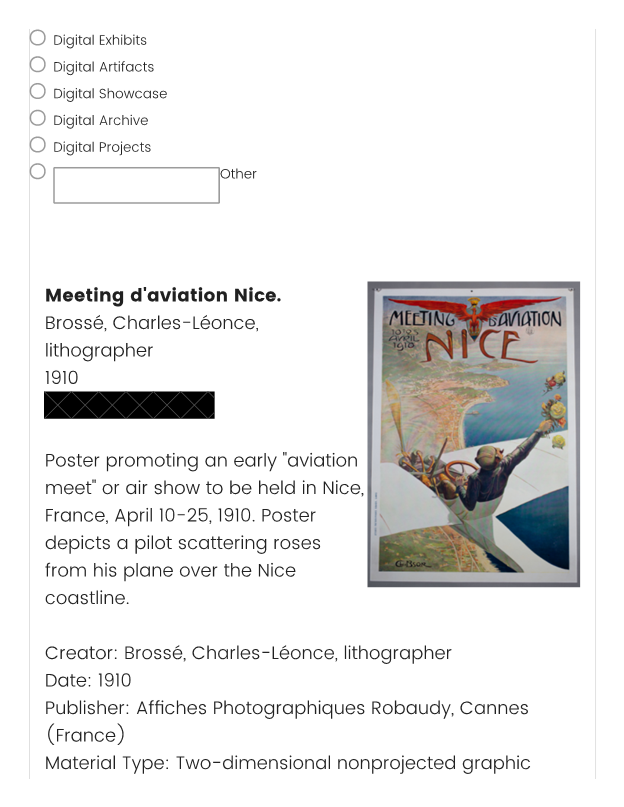

Meeting d’aviation Nice. |

N=14 (33%) |

N=7 (17%) |

N=4 (10%) |

N=3 (7%) |

N=13 (31%) |

N=1 (2%) |

Digital Collections |

|

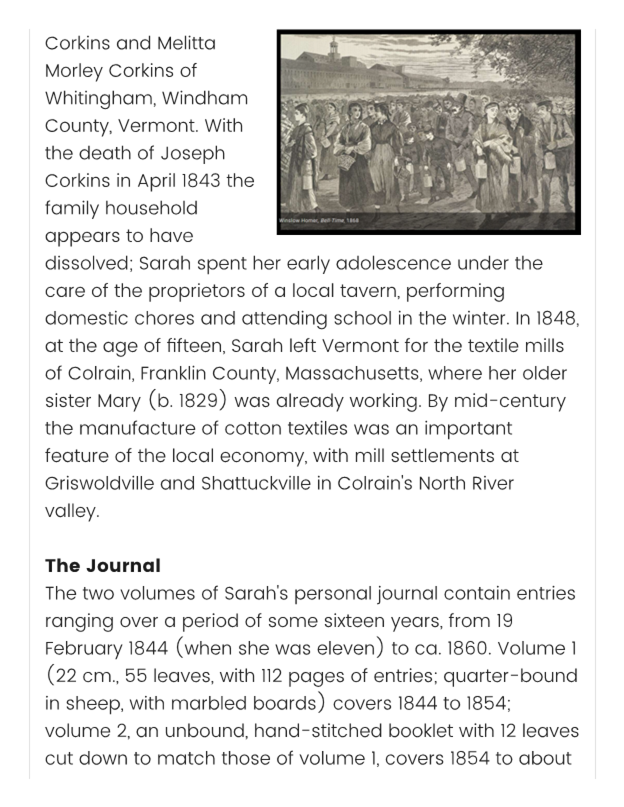

The Author; The Journal |

N=9 (21%) |

N=12 (29%) |

N=11 (26%0 |

0 |

N=7 (17%) |

N=3 (7%) |

Digital Exhibits |

|

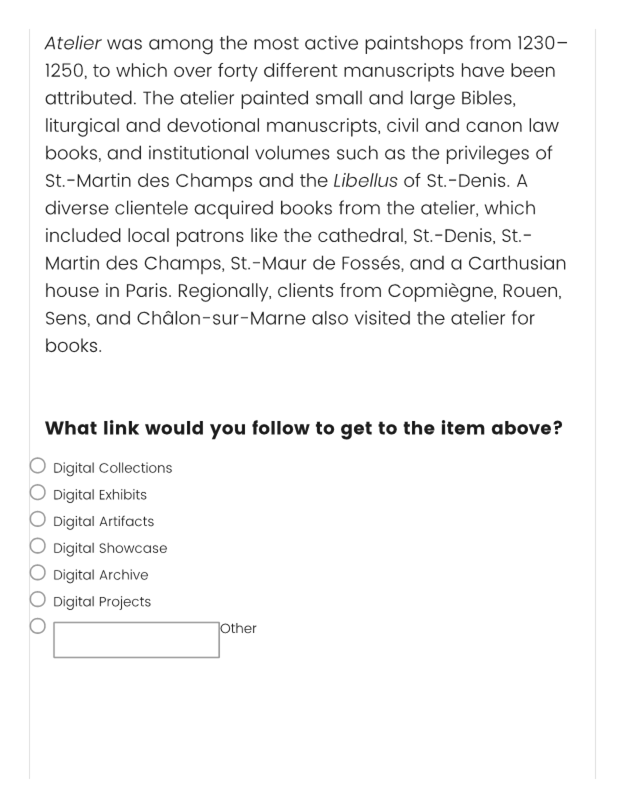

The Ferrell Bible |

N=6 (14%) |

N=6 (14%) |

N=16 (38%) |

N=3 (7%) |

N=11 (26%) |

0 |

Digital Exhibits |

|

New edition of a general Collection of the ancient Irish music |

N=16 (38%) |

N=4 (10%) |

n=7 (17%) |

n=4 (10%) |

n=8 (19%) |

n=3 (7%) |

Digital Collections |

Discussion

The results of our study suggested that, among our users, there was no

consistent understanding of the terms most commonly used

by libraries to describe the types of digitized cultural heritage items found

on our digital exhibits and collections platforms. Without a common

understanding or interpretation of these terms, using those terms alone as link

labels would not be enough for most users to clearly understand the types of information they would find by following those links.

Similarly, the other terms suggested by our students were not well-understood

across the board in the follow-up survey. There were several terms that showed

up more frequently in the student responses, such as “archives” and

“artifacts.” However, these terms have specific meaning to librarians,

curators, archivists, and other researchers. As

mentioned earlier, using them to describe our

digitized and contextualized content would not be entirely accurate and may in

fact cause confusion for more advanced researchers who have specific associations

with these terms. As such, we would not use these terms as link text to broadly

label entire digital collections or exhibits sites because of the additional

confusion this would cause for internal workflows and the work of another key

constituency: advanced researchers.

Additionally, more graduate students selected the term “Digital Projects”

than undergraduates in the second survey. While this term seemed to resonate

well with this small group of users, it is an all-encompassing term that may not

provide enough information to users about what they might find at a link with

that label. Other researchers using card sorting have found that some terms can

be so broad and vague as to be unhelpful, such as “resources” (Hennig, 2001)

and “services” (Hennig, 2001; Duncan & Holliday, 2008). We suspect that

“digital projects” might be one such term.

While beyond the

scope of this study, an interesting data point emerged related to scholarly

articles, e-books, and datasets: nearly half of respondents indicated they

would expect to see e-books and scholarly journal articles in Digital

Collections (e-books, n=26, and scholarly journal articles, n=24) and Digital

Archives (e-books, n=19, and scholarly journal articles, n=22). A significant

number of participants would expect to see datasets and databases in Digital

Archives (n=15) (See Table 3). Future research could explore this to better

understand why users expected to find datasets and databases in digital

archives, and whether it, too, is a term that is poorly understood.

Based on these results, we determined the most user-friendly way to link to

these resources was to use the term we—librarians, curators, and

archivists—think is most accurate as the link text based on our professional knowledge

and provide a brief description of what each site contains in

order to provide necessary context. For example, the link entitled

“Digital Exhibits,” could also include the brief description: “In-depth

explorations of a theme using items from our collections, curated by our

librarians and staff.” This solution allows librarians and archivists to refer

to various digital collections or exhibits sites in a clear, distinct, and

consistent manner, and the brief description provides necessary additional

context and serves as a teaching tool to help our users understand what we mean

by these link label terms. The brief description, when appropriate, can also

include words that students might be looking for, such as “archives” and

“artifacts,” without making inaccurate claims about our digital exhibits or

collections. Lastly, this approach also allows our library to leverage specific

and meaningful terms to help educate users on library resources. Less than a

quarter of respondents expected to see descriptive information (metadata) or

related items in any of the options (see Table 3). In leveraging precise

language to concisely describe the links and supplementing that with additional

descriptive text, we can educate users not only on the meanings of these words,

but also on the different types of resources and support available to them. In

other words, while our profession has a tendency to

use terms like digital collections and digital exhibits interchangeably, it is

critical that we use terms precisely—not necessarily because students

intuitively know the difference, but because this is an opportunity to educate

users on different ways to access content online.

These

descriptions could be added in a variety of ways. The link could be accompanied

by a brief phrase or sentence to provide context. This option would require web

content or menu structure that allows for links to have additional text next to

them. Another option is to provide the descriptive text in a tooltip that

appears when a user hovers over the link. The method for providing descriptive

text could be tested further in a usability study.

Limitations

This study has a

few limitations. First, this was a relatively small sample size: 32 respondents

completed the first survey, and 42 respondents completed the second survey.

While there was a mixture of undergraduates and graduate students who responded

to each survey, the total number of respondents to each survey overall was not

large. Additionally, respondents skewed heavily toward affiliation with the

College of Arts and Letters. Approaches to research and experience with and

awareness of digital collections and digital exhibits may be different among

students with different primary college affiliations. Due to limited responses

from some of the colleges, there were not enough data to be able to determine

whether there were any significant disciplinary differences for preferred link

labels. Finally, these surveys were sent only to students at the University of

Notre Dame. While these survey results represent the thoughts of students at

one campus, the results may provide a launching point for other institutions’

usability studies.

Conclusion

In this research

study, we set out to learn more about users’ understandings of terms related to

digital libraries, specifically to disambiguate a digital collections site from

a digital exhibits site. Following a literature review, the authors conducted

an environmental scan of ARL Libraries’ websites to get a clearer picture of

how peer institutions were approaching this distinction. Without a consensus,

the authors conducted two surveys of undergraduate and graduate students at an

R1 institution. The results suggested that there was no clear understanding of

various terms among users. We suggested the best path forward in labeling the

links of these sites was to provide additional contextual information to help

educate users and make links clearer.

These examples demonstrated the importance of partnering user input and

feedback with professional expertise. While our first instinct may be to

leverage language that is most familiar to some users, this approach not only

minimizes our professional contributions and expertise, but also can be

confusing to other users. This study affirmed the importance of using

meaningful language: while broad terms like “digital project” might be catchy,

they are ultimately too broad to be helpful. There was no consensus among the

undergraduate and graduate students surveyed as to what these terms might actually lead to.

This study, building on the work of previous scholars (Burns, 2019)

included examples of digitized items from our library system; however, the

terms tested were not necessarily specific to our context. Therefore, the

results of this study may provide useful guidance or considerations for other

libraries and archives attempting to identify appropriate link language on

their own organizations’ websites or as a jumping off point for developing

their own user studies. As libraries, archives, museums, and other cultural

heritage organizations continue to distribute content online, build and

implement new services, and even consolidate and sunset previous services,

using specific terms to clearly label and disambiguate links will be of

continued importance.

Author Contributions

Melissa Harden:

Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review

& editing Anna Michelle Martinez-Montavon: Formal

analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review &

editing Mikala Narlock: Funding acquisition,

Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

References

Brucker, J. (2010). Playing with a

bad deck: The caveats of card sorting as a web site redesign tool. Journal of Hospital Librarianship, 10(1), 41-53. https://doi.org/10.1080/15323260903458741

Burns, D., Sundt, A., Pumphrey, D., & Thoms,

B. (2019). What we talk about when we talk about digital libraries: UX

approaches to labeling online special collections. Weave: Journal of Library User Experience, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.3998/weave.12535642.0002.102

Budiu, R. (2020,

February 2). Information scent: How users

decide where to go next. Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/information-scent/

Chowdhury, S., Landoni,

M., & Gibb, F. (2006). Usability and impact of digital libraries: A review.

Online Information Review, 30(6),

656-680. https://doi.org/10.1108/14684520610716153

Denzer, J. (2015). Digital collections and exhibits. Rowman

& Littlefield.

Dickstein, R., & Mills, V. (2000). Usability testing at the University

of Arizona Library: How to let the users in on the design. Information Technology and Libraries, 19(3), 144–151.

Diller, K. R., & Campbell, N. (1999). Effective library web sites: How

to ask your users what will work for them. Proceedings

of the Integrated Online Library Systems Meeting, 14, 41–54.

Duncan, J., & Holliday, W. (2008).

The role of information architecture in designing a third-generation library

web site. College & Research

Libraries, 69(4), 301-318. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.69.4.301

Faiks, A., & Hyland,

N. (2000). Gaining user insight: A case study illustrating the card sort

technique. College & Research

Libraries, 61, 349–357. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.61.4.349

Ford, E. (2013). Is digital better than analog? Considerations for online

card sort studies. College & Research

Libraries News, 74(5), 258–261.

Francoeur, S. (2021a, March 5). More

thoughts on language usage and design.

Beating the Bounds: Library Stuff I’m Thinking About. https://www.stephenfrancoeur.com/beatingthebounds/2021/03/05/more-thoughts-on-language-usage-and-design/

Francoeur, S. (2021b, March 4). Watching

the language parade of our users. Beating the Bounds: Library Stuff I’m

Thinking About. https://www.stephenfrancoeur.com/beatingthebounds/2021/03/04/watching-the-language-parade-of-our-users/

Gillis, R. (2017). “Watch your language!”: Word choice in library website

usability. Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library and Information

Practice and Research, 12(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v12i1.3918

Guay, S., Rudin, L.,

& Reynolds, S. (2019). Testing, testing: A usability case study at

University of Toronto Scarborough Library. Library Management, 40(1/2), 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-10-2017-0107

Hennig, N. (2001). Card sorting usability tests of the MIT Libraries’ web

site: Categories from the user’s point of view. In N. Campbell (Ed.), Usability

assessment of library related web sites: Methods and case studies (pp. 88–99).

LITA, American Library Association.

Hepburn, P., & Lewis, K. M. (2008). What’s in a name? Using card

sorting to evaluate branding in an academic library’s web site. College &

Research Libraries, 69(3), 242-251. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.69.3.242

Kelly, E. J. (2014). Assessment of digitized library and archives

materials: A literature review. Journal of Web Librarianship, 8(4), 384–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2014.954740

Kupersmith, J. (2012). Library

terms that users understand. UC Berkeley Library.

http://escholarship.org/uc/item/3qq499w7

Lewis, K. M., & Hepburn, P. (2010). Open card sorting and factor

analysis: A usability case study. The Electronic Library, 28(3), 401–416. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02640471011051981

Mendoza College of Business. (2022). About Mendoza. Retrieved September 11,

2022, from https://mendoza.nd.edu/about/

Nielsen, J. (2009, August 23). Card sorting: Pushing users beyond

terminology matches. Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/card-sorting-terminology-matches/

Office of Strategic Planning & Institutional Research. (2022). Common

Data Set 2021-2022 [Data set]. University of Notre Dame. https://www3.nd.edu/~instres/CDS/2021-2022/CDS_2021-2022.pdf

Paladino, E. B., Klentzin, J. C., & Mills, C.

P. (2017). Card sorting in an online environment: Key to involving online-only

student population in usability testing of an academic library web site?

Journal of Library & Information Services in Distance Learning, 11(1–2),

37–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2016.1223967

Polger, M. (2011).

Student preferences in library website vocabulary. Library Philosophy and

Practice, 1-16. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/618

Robbins, L. P., Esposito, L., Kretz, C., & Aloi, M. (2007). What a user wants: Redesigning a library's

web site based on a card-sort analysis. Journal of Web Librarianship, 1(4),

3-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322900802111346

Rowley, P., & Scardellato, K. (2005). Card

sorting: A practical guide. Access, 2, 26–28

Spencer, D. (2009). Card sorting:

Designing usable categories. Rosenfeld Media.

Sundt, A., & Eastman, T. (2019). Informing website navigation design

with team-based card sorting. Journal of Web Librarianship, 13(1), 37–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2018.1544873

University of Notre Dame. (2022). About: Notre Dame at a

glance. Retrieved September 11, 2022, from https://www.nd.edu/about/

Whang, M. (2008). Card-sorting usability tests of the WMU Libraries’ web

site. Journal of Web Librarianship, 2(2–3), 205–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322900802205940

Appendix A

Survey Instruments Distributed Through Electronic Mailing

Lists

Survey 1

Survey 2

If

If