Research Article

Chat Transcripts in the Context

of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Analysis of Chats from the AskAway Consortia

Barbara Sobol

Public Services Librarian

University of British Columbia, Okanagan

Kelowna, British Columbia, Canada

Email: barbara.sobol@ubc.ca

Aline Goncalves

Information Literacy/Reference Librarian

Yukon University Library

Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada

Email: agoncalves@yukonu.ca

Mathew Vis-Dunbar

Data and Digital Scholarship Librarian

University of British Columbia, Okanagan

Kelowna, British Columbia, Canada

Email: Mathew.Vis-Dunbar@ubc.ca

Sajni Lacey

Learning and Curriculum Support Librarian

University of British Columbia, Okanagan

Kelowna, British Columbia, Canada

Email: sajni.lacey@ubc.ca

Shannon Moist

Head of Reference Services

Douglas College

New Westminster, British Columbia, Canada

Email: moists@douglascollege.ca

Leanna Jantzi

Head, Fraser Library

Simon Fraser University

Surrey, British Columbia, Canada

Email: leanna_jantzi@sfu.ca

Aditi Gupta

Engineering and Science Librarian

University of Victoria Libraries

Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

Email: aditig@uvic.ca

Jessica Mussell

Distance Learning and Research

Librarian

University of Victoria Libraries

Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

Email: jmussell@uvic.ca

Patricia L. Foster

Public Services/AskAway Coordinator

University of British Columbia, Point Grey Campus

Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Email: patricia.foster@ubc.ca

Kathleen James

Instruction Librarian

Mount Royal University

Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Email: kjames@mtoroyal.ca

Received: 12 Dec. 2022 Accepted: 13 Mar. 2023

![]() 2023 Sobol, Goncalves, Vis-Dunbar, Lacey, Moist, Jantzi, Gupta, Mussell, Foster,

and James.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2023 Sobol, Goncalves, Vis-Dunbar, Lacey, Moist, Jantzi, Gupta, Mussell, Foster,

and James.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Data Availability: Sobol, B., Goncalves, A., Vis-Dunbar, M., Lacey, S., Moist, S., Jantzi,

L., Gupta A., Mussell, J., Foster, P., & James, K. (2023). Data:

Chat transcripts in the context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Analysis of chats

from the AskAway Consortia. Open Science Framework, V1. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/FESWQ

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30291

Abstract

Objective

– During the COVID-19 pandemic, the majority of

post-secondary institutions in British Columbia remained closed for a prolonged

period, and volume on the provincial consortia chat service, AskAway, increased

significantly. This study was designed to evaluate the content of AskAway

transcripts for the 2019-2020 and 2020-2021 academic years to determine if the

content of questions varied during the pandemic.

Methods – The following programs were used to evaluate the dataset

of more than 70,000 transcripts: R, Python (pandas), Voyant Tools and

Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC).

Results

– Our findings indicate that the content of questions remained largely

unchanged despite the COVID-19 pandemic and the related increase in volume of

questions on the AskAway chat service.

Conclusion – These findings suggest that

the academic libraries covered by this study were well-poised to provide

continued support of patrons through the AskAway chat service, despite an

unprecedented closure of physical libraries, a significant increase in chat

volume, and a time of global uncertainty.

Context

This study was designed to evaluate the content of AskAway transcripts for

the 2019-2020 and 2020-2021 academic years in response to this question: Did

the types of questions, or the substance of those questions, change during the

COVID-19 pandemic? Our hypothesis was that the questions would differ when

compared with the pre-pandemic period. We were curious about what could be

learned about academic library patron needs during this time, based on changes

in language usage and the types of questions asked. What could we ascertain

about reference needs in this time period, and how

could that help us to prepare for future service disruptions? Could anything be

discovered about unique information needs during a pandemic?

Chat reference in post-secondary libraries in British Columbia, Canada is

provided through AskAway, which is described as “a collaborative service that

is supported and staffed by post-secondary libraries from BC and the Yukon” and

comprises 29 member libraries (BC ELN, 2022a). The member libraries represent a

diverse set of institutions, from private two-year colleges to large publicly

funded research universities that span an enormous geographic area and

represent both rural and urban settings (BC Stats, 2018). AskAway was

established in 2006 and has since been an important part of library services at

all participating institutions. When the pandemic was declared in March 2020

(World Health Organization, 2022), physical libraries were closed and chat

reference was perceived by most libraries as the primary means of service

provision. This shift is described by Hervieux (2021) as moving chat reference

from the margins of a service model to a “vital community service in a time of

great uncertainty” (p. 267), a sentiment echoed by Radford et al. (2021) who

describe chat during the pandemic as a “premier essential user service” (p.

106).

The long-term closure of academic libraries in British Columbia was

unprecedented, with many libraries remaining closed for up to 18 months (BC

ELN, 2021). During the height of the pandemic, demand for AskAway chat

reference services increased by 62% over pre-pandemic years. Post-secondary

students also reported severe disruptions in their studies, finances

and career plans (Statistics Canada, 2020). Foreshadowing our findings, Lapidus

(2022) and Watson (2022) nonetheless found that “for some institutions at

least, the existing online reference infrastructure was capable of absorbing

the demand during the pandemic” (Watson, 2022, p.11).

In order to address the

pandemic-specific questions that we had of the dataset, the standard practice

of comparing academic years was deemed to be inadequate. As such, we created a

timeline for analysis tied to key dates in the pandemic. September 2019 through

March 2020 is the pre-pandemic timeline; the pandemic was declared on March 11,

2020, and BC post-secondary institutions closed on different dates throughout

the month. April 2020 through December 2020 is the main pandemic period when

institutions were fully online and library buildings were primarily closed.

January 2021 through August 2021 represents a lessening of restrictions in BC

and the reopening of libraries on different dates in advance of the 2021-2022

academic year; we refer to this period as late pandemic. The natural ebb and

flow of the academic year is not reflected in the pandemic timelines and each time period includes regular term peaks and intersession

breaks.

Literature Review

Academic Library Chat Reference Analysis

Virtual reference is defined as a “reference service initiated

electronically for which patrons employ technology to communicate with public

services staff without being physically present” (Reference and User Services

Association, 2017). Academic library virtual reference services began in the

1990s and were in widespread use by the 2000s, allowing services to reach users

at their point of need (Francoeur, 2001; Sloan, 1998). Research has found that

chat services have resulted in a decrease in library in-person visits as more

people access Web resources on home computers (Francoeur, 2001; Harlow, 2021).

With physical space closures and public safety measures being implemented by

libraries during the COVID-19 pandemic, reliance on chat reference increased

which resulted in a renewed urgency to examine this topic (De Groote &

Scoulas, 2021; Hervieux, 2021; Kathuria, 2021). While there are many studies

evaluating different aspects of chat reference, this literature review is

focused on methodological approaches for unearthing meaning and evaluating

language in academic library chat transcripts.

In an effort to discover and understand the complex behaviors, experiences, and

interactions between virtual reference chat users and librarians, chat

transcript analysis has moved beyond usage statistics and standardized question

tagging to a more contextualized examination of transcripts using

transcript-harvested data-based topic modeling, sentiment analysis, and

visualizations (Wang 2022, Chen & Wang, 2019; Ozeran & Martin, 2019).

This developing analysis trend has technical limitations in its implementation

and the lack of a standardization for evaluation (Chen, 2019; Grabarek &

Sobel, 2012; Harlow, 2021; Kathuria, 2021; Ozeran & Martin, 2019). Grabarek

and Sobel (2012) highlight the challenges of anonymous data in evaluating

social and emotional meaning. Further exploration with larger datasets and chat

transcripts over longer and various date ranges for comparison may elucidate

more areas of interest, and visualization tools will be helpful for analysis

(Chen & Wang, 2019; Ozeran & Martin, 2019). Sharma, Barrett and

Stapelfeldt (2022) utilize a Python library and Tableau for visualization,

demonstrating the utility of mixed method analysis. Walker and Coleman (2021)

explore machine learning as a method for examining the complexity of chats with

a large dataset.

The use of coding methods is heavily utilized in chat transcript analysis

to examine meaning and satisfaction, yet large datasets often make this

impractical without relying upon sampling. Schiller (2016) used the

Cultural-Historical Activity Theory framework to conduct their analysis,

generating a codebook and a cluster analysis to determine relationships. Logan,

Barrett, and Pagotto (2019) used SPSS to code chat user satisfaction based on

transcripts and exit surveys. Harlow (2021) coded nursing chat transcripts

using Atlas.ti to evaluate reference efficacy. Logan and Barrett (2018) coded a

sample of chats to evaluate the relationship between provider communication

style and patron willingness to return; chi-square tests were used to assess

this relationship. Kathuria (2021) utilized a two-part method of grounded

theory tagging followed by sentiment analysis using R to evaluate positive and

negative sentiments. Grounded theory has been used in many studies as part of a

mixed methods analysis to examine meaning (Harlow, 2021; Mungin, 2017; Smith et

al., 2016).

Chat Reference in Libraries During COVID-19

A number of studies which examine chat services and transcripts in the

context of the COVID-19 pandemic have already been published, and many found an

increase in chat volume when academic libraries, along with their institutions,

closed their doors and shifted to remote instruction and services (De Groote

& Scoulas, 2021; Hervieux, 2021; Kathuria, 2021; Lapidus, 2022; Radford et

al., 2021). When comparing chat transcripts between Fall 2019 and Fall 2020,

Hervieux (2021) found that while “percentages of each type of interaction were

fairly similar…with known items, circulation and reference queries making up

the majority of the questions asked,” there was a “substantial difference” in

questions about branch library information due to COVID-protocols and procedures

applied to study spaces (p. 275-6).

Kathuria (2021) found that “questions about accessing and returning the

physical collection grew the most during COVID” (p. 112). Other questions that

increased included those regarding fines and fees, library hours and technical

troubleshooting (Kathuria, 2021). An increase in questions regarding course and

assignment support and assignments has also been noted (Hervieux, 2021;

Kathuria, 2021). Alternatively, Watson (2022) compared the University of

Mississippi Libraries’ pandemic chat data to a pre-pandemic period and found no

increase in chats and no significant difference in word frequency in chat

transcripts. Graewingholt et al., (2022) argue that review of chat transcripts,

regardless of the pandemic context, can further support revisions, adjustments,

and improvements to library services.

Multiple methods of analysis for examining chat reference during the

COVID-19 pandemic have been utilized. Hervieux (2021) used qualitative coding

and quantitative metadata analysis to examine both the complexity and duration

of chats. Hervieux (2021) concluded that more questions were being asked, more

downtime during a chat was occurring, and that “librarians and patrons use more

relational cues during their interactions” (p. 277). Kathuria (2021) used a

grounded theory of analysis relying on coding and sentiment analysis in R and

found an increase in negative sentiment when comparing pre-pandemic and

pandemic chats. Radford, Costello & Montague (2021) relied on surveys and

interviews to inform their examination of patron chat behavior and service

perceptions. DeGroote & Scoulas (2021) also used patron surveys and paired

this with statistical analysis to examine library use patterns during COVID-19.

Lapidus (2022) conducted statistical analysis of metadata to understand

reference services overall, including chat. Watson (2022) analyzed metadata and

word frequency utilizing NVivo and Voyant in a multi-method approach not

dissimilar from that reported in this study. Finally, Graewingholt et. al.

(2022) started with machine classification followed by manual coding to

understand trends in questions and inform training. Consensus on how to best

evaluate large chat datasets has not yet emerged within the literature.

Methods and Tools

Data Acquisition

AskAway chat data for this study covering September 1, 2019 to August 31,

2021 were obtained from software vendor LibraryH3lp. Names, email addresses,

student numbers, and other information that could lead to patron or service

provider identification were removed by LibraryH3lp in accordance with the BC

ELN privacy policy. In addition, four categories of chats were removed prior to

data acquisition: chats from a university that withdrew from the service early

in the timeline being studied, chats where the privacy script was employed by

service providers, practice chats, and chats fewer than five seconds in length.

Based on these criteria, LibraryH3lp provided two datasets: AskAway

transcripts, containing chats between patron and provider with each chat as an

individual text file for a total of 70,728 chats; and AskAway metadata,

containing chat metadata, including start date, start time, queue, duration,

and tags. Tags are standardized categories applied to chats by service

providers (AskAway, 2022). This second data set consisted of 73,483 rows, one

row for each chat, suggesting 2,754 additional records than were included in

the transcript data set; this discrepancy is discussed below.

Data Description

AskAway transcripts are composed of four elements: a header with metadata,

system text (like a welcome message), provider text, and patron text. These

transcripts, like most chat data, are not well-structured. The informal nature

of chat communication and the lack of standardization or error correction

across chats (as an example, 'Thank you', vs 'Thank-you', vs 'Thankyou', vs

'Thnkyou'), present challenges in derived analyses. These challenges are

further exacerbated by a variety of other features of chat data: the use of

shorthand, such as emoticons and acronyms; a need to be expressive in a text

environment, resulting in things like excessive punctuation; fast typing

resulting in misspellings and excess white space; and content pasted from other

sources introducing a variety of printed and non-printed characters. These

features of the data set make even basic descriptive statistics, such as word

counts, challenging. Conceptually, we can see this when comparing the terms

'meta data' and 'metadata', counted as two words and one word, respectively.

AskAway metadata is highly structured data and consists

of two categories: system-generated and provider-generated. System-generated

metadata include variables such as time stamps, institution, and duration.

Provider-generated metadata consists of tags, of which there are thirty

available (AskAway, 2022). Service providers select those most appropriate to

the chat to represent the interaction; multiple tags can be selected and there

is no free-text option. In March 2020, AskAway advised service providers to

apply the tag “Other” to COVID-19 chats and in June 2020, AskAway introduced a

new COVID-19 tag to indicate if a question was specifically related to an

aspect of the pandemic.

LibraryH3lp was unable to provide an explanation for the

discrepancy between number of transcripts provided and number of chats

suggested by the metadata dataset. To investigate this further, metadata was

extracted from the transcripts and compared against the metadata dataset. While

a definitive conclusion could not be derived, noted anomalies such as the

duration time stamps occasionally being off by a second, suggest minor errors

in the collection of data attributed to this inconsistency. Representing just

under 4% of the transcript data, this discrepancy was considered manageable for

the purposes of this study.

We added a field to the metadata to classify

participating institutions by the size of their student body using the value of

Full-Time Equivalent (FTE). FTE numbers were derived from BC ELN (2022b), and

divide post-secondary institutions into three categories, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1

AskAway Post-Secondary Institutions by FTE

|

Institution size |

FTE Count |

Number of Institutions |

|

Small |

4,999 or less |

18 |

|

Medium |

5,000-9,999 |

9 |

|

Large |

10,000 or more |

4 |

Data Cleaning & Preparation for Analysis

AskAway transcript data was iteratively cleaned and organized using R. The

text chats were initially merged into a single data set, and all

system-generated text and metadata stripped from the main corpus; metadata

remained associated with the text and allowed for subsequent subsetting of the

data. Several subsets of the data were produced, including patron-only

transcripts, provider-only transcripts, and time series transcripts. As part of

this process, general cleaning included removal of excess white space,

conversion to lowercase, and stripping of punctuation. Single text files of

each subset were then produced for analysis.

The AskAway metadata dataset arrived clean with no post-processing needed,

other than including additional data about the FTE category. To prepare the

data for use in LIWC, a small modification to the original datasets was made:

replacing the strings ‘https://’ and ‘http://’ with the string ‘URL,’ as the

element ‘:/’ was being interpreted as an

emoticon and skewing the scores for the tone dimension analysis.

Selection of Text Analysis Tools

With a dataset of 70,728 items, the research team used multiple approaches in an attempt to find patterns and meaning. Uncertain of

which tools and techniques would be the most appropriate for examining meaning

in large bodies of chat text, we first ran a random sample of the LIWC, AskAway

transcript (n = 3,800) through a series of text analysis applications. This

allowed us to assess the general format and contents of the dataset and to

identify the most appropriate tools to address our research questions. The test

analysis was run in the following programs: R, Atlas.ti, NVivo, Python

(pandas), Voyant, LIWC, and OpenRefine. Based on functionality and researcher

expertise, R and Python (pandas) were selected for metadata and quantitative

chat analysis. LIWC and Voyant were selected as tools to explore meaning in the

chat transcripts.

Voyant Tools

Voyant Tools is a suite of Web-based textual analysis

tools used in digital humanities (Sinclair & Rockwell, 2022). Voyant allows

for text files to be explored and visually represented in an easy to manipulate

interface; it is particularly useful for examining patterns within texts. Of particular relevance to this analysis were the Cirrus,

Document Terms, Terms Berry, and Trends tools; these were used to determine

patterns and meaning within each dataset and between them.

Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC)

LIWC is a software program focused on identifying

people’s social and psychological states from the language they use. LIWC

achieves this by calculating word count distributions in psychologically

meaningful categories (Tausczik &

Pennebaker, 2010). The current

version, LIWC-22, uses over 100 built-in dictionaries consisting of words, word

stems, emoticons, and other verbal structures to capture several psychological

categories (LIWC, n.d.). Since our objective was to assess if there was a

difference between the types of inquiries received by AskAway throughout the

pandemic, and not to evaluate linguistic characteristics per se, we focused on

the summary dimensions, described in Table 2.

Table 2

LIWC Summary Dimensions

|

Summary dimensions |

Description |

|

Analytic |

Captures the use of formal, logical, and hierarchical thinking patterns.

Low scores correspond to intuitive, personal, and less rigid language. High

scores suggest more formal or academic language correlated with higher grades

and reasoning skills. |

|

Clout |

Refers to language related to social status, confidence, or leadership. |

|

Authenticity |

Describes self-monitoring language, associated with levels of

spontaneity. Higher scores in this category mean use of less “filtered”

language, while prepared texts tend to have lower scores. |

|

Tone |

Puts positive and negative emotional tones into a single summary

variable. The higher the number, the more positive the language, while scores

below 50 suggest a more negative tone.

|

Analysis

Metadata Analysis

Using both R and Python (pandas), the metadata for the

full dataset was analyzed for insights into question types, distributions

and trends. In general, the data indicate changes in volume more so than any

other element. For example, the pandemic was officially declared on March 11,

2020 and March 23, 2020 was the busiest single day on AskAway throughout the

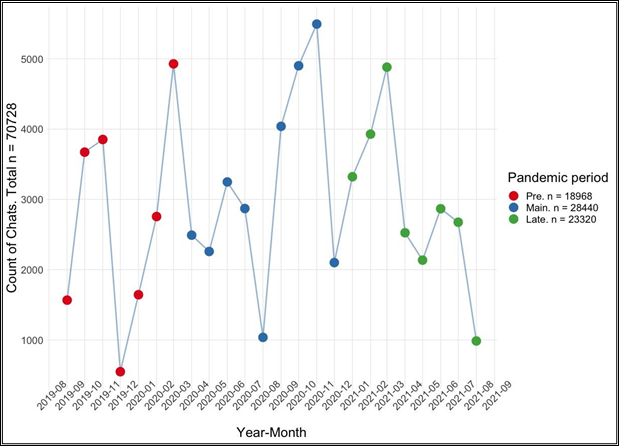

study period. Figure 1 below depicts the distribution of questions asked on

AskAway between September 2019 and August 2021, totaled by month, and

colour-coded to represent the pandemic timeline.

Figure 1

Total chats by month and pandemic timeline.

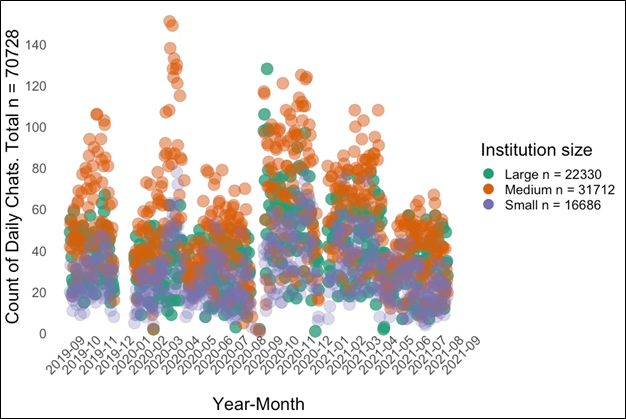

The AskAway service supports a variety of post-secondary

institutions that differ in size, program type, geography, and urban/rural

locality. Figure 2 depicts the distribution of questions asked over time by the

size of the post-secondary institution by enrollment. While the pattern in the

data follows the same trajectory as is depicted in Figure 1, when the data is

broken out by institution size, we see that medium-sized institutions

consistently account for a high proportion of questions asked. We also see

that, after the pandemic was declared, the number of questions asked from the

larger institutions accounts for a substantial portion of the increase in

volume. Despite these increases in volume from larger institutions, which

include the research-intensive universities, there is no evidence in our data

that the question types themselves were altered.

Figure 2

Timeline of total chats by institution size and pandemic timeline.

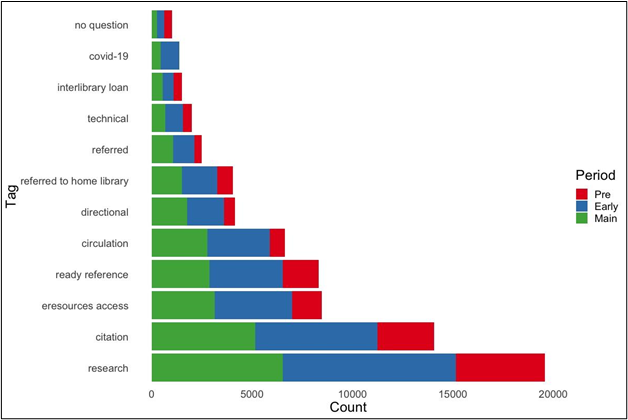

AskAway tags are well-defined for collective usage

(AskAway, 2022) and analysis of them shows very clearly that, from the service

provider’s perspective, the type of questions asked on AskAway did not change

substantially during the pandemic. Figure 3 demonstrates the remarkable

consistency in the types of questions asked throughout our study period through

a display of the top 10 tags in our dataset, isolated by pandemic period. Note

that there are 12 tags in Figure 3. The top 10 tags for each period were extracted

and then collated; not all tags below would have been in the top 10 for the dataset as a whole. The top 7 tags in Figure 3 were in the

top 10 for all 3 periods, as was the tag 'technical'. The remaining 4 tags were

in the top 10 for only 1 or 2 periods (no question in 'pre', COVID-19 in

'early', InterLibrary Loan in 'pre' and 'main', and referred in 'early' and

'main').

A few other aspects of the tags warrant highlighting.

Circulation, referrals to “home library,” and directional questions all increased

from April 2020 onward. Interlibrary loan (ILL) questions are absent in the

main pandemic dataset as ILL services were unavailable globally for much of

that time. The presence of general referrals - directing patrons to services

outside of the library - only in the main- and late-pandemic data suggests the

important role that libraries played as a general campus service. The COVID-19

tag emerges in the top 10 tags during the main pandemic period but does not

persist beyond December 2020. Despite these differences, we see remarkable

consistency especially in those that account for the majority

of the volume of activity.

Figure 3

Figure 3

Top ten chat tags displayed by pandemic timeline.

Transcript Analysis

Table 3 details the transcripts in the pandemic timeline which form the

basis of our subsequent analysis.

Table 3

Pandemic Timeline Datasets

|

Timeline |

Transcript Datasets |

Chats Per Dataset |

|

Pre-pandemic: September 2019 - March 2020 |

all chats (patron & provider) patron only provider only |

18,968 |

|

Main-pandemic: April 2020 through December 2020 |

all chats (patron & provider) patron only provider only |

28,440 |

|

Late-pandemic: January 2021 - August 2021 |

all chats (patron & provider) patron only provider only |

23,320 |

Table 4

Voyant Tools Analysis of Patron Chat

|

|

Pre-pandemic |

Main-Pandemic |

Late-Pandemic |

|

Average words per sentence |

39.5 |

37.8 |

36.1 |

|

Vocabulary density |

0.030 |

0.024 |

0.027 |

|

Readability Index |

9.603 |

9.406 |

9.493 |

|

Total words |

1, 683, 539 |

2, 959,334 |

2, 341, 374 |

|

Unique words |

50, 039 |

71, 373 |

62, 735 |

Table 4 displays the summary report for the patron chat

for each time period in Voyant Tools. These are values

that Voyant Tools applies as a default to all analyses: average words per

sentence, vocabulary density, readability, total words

and unique words (Sinclair & Rockwell, 2022). The Readability Index is a

calculation based on the BreakIterator class, which is a natural-language

coding technique to determine word boundaries and syntax in text (Oracle,

2022). While these values are not inherently insightful, when examined in

comparison across the time periods they demonstrate remarkable similarity on

each metric, reinforcing our overall findings.

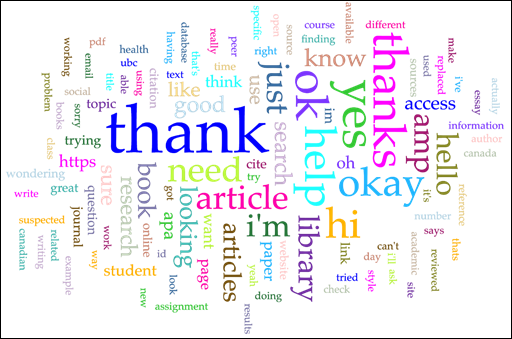

Word frequency was used to explore patron voice in the

transcripts across each pandemic time period. There

are a total of 214,418 unique words in all of the

patron transcripts. Using R, we extracted the 1,000 most frequently used words,

consisting of 4 or more characters, from each time period.

There are 1,135 unique terms in total that meet these criteria, of which 871

are in all 3 time periods, and 264 are in only 1 or 2 of the time periods.

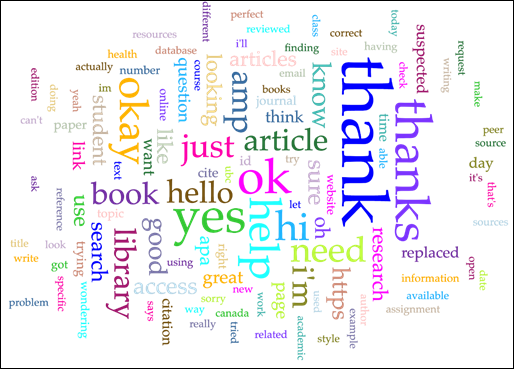

Figures 4-6 present word clouds of the top 115 words from patron-only

transcripts with the size of the word mapped to its frequency.

Figure 4

Pre-pandemic patron chat.

Figure 5

Main-pandemic patron chat.

Figure 6

Late-pandemic patron chat.

LIWC was employed to identify general trends in the sentiments expressed in

our dataset, an approach similar to Kathuria’s (2021)

sentiment analysis. The LIWC dimensions of analytic, clout, authentic, and tone

were used to evaluate potential changes in both patron and provider

transcripts. Linguistic scores between patron and provider were compared to

evaluate similarities or differences in language used. Table 5 presents the

scores and change percentages for the LIWC dimensions for both patron and

provider transcripts.

Table 5

LIWC Dimensions Analysis By Pandemic Timeline

|

|

Word Count |

Analytic |

% change |

Clout |

% change |

Authentic |

% change |

Tone |

% change |

|

Provider Chats |

|||||||||

|

Pre |

3,633,999 |

52.66 |

n/a |

81.13 |

n/a |

28.69 |

n/a |

80.78 |

n/a |

|

Main |

6,149,448 |

52.62 |

-0.07 |

79.2 |

-2.37 |

27.03 |

-5.78 |

76.43 |

-5.38 |

|

Late |

4,997,628 |

54.51 |

3.60 |

80.24 |

1.31 |

25.99 |

-3.85 |

77.37 |

1.22 |

|

Patron Chats |

|||||||||

|

Pre |

1,682,967 |

39.28 |

n/a |

15.2 |

n/a |

55.89 |

n/a |

89.32 |

n/a |

|

Main |

2,959,063 |

37.92 |

-3.46 |

15.33 |

0.85 |

56.72 |

1.48 |

89.52 |

0.22 |

|

Late |

2,340,394 |

38.7 |

2.05 |

15.72 |

2.54 |

56.71 |

-0.01 |

91.3 |

1.99 |

Analytic scores were nearly identical for providers pre-pandemic and in the

beginning of the pandemic, indicating similar levels of formality in language.

An increase of 3.59% was observed in the late phase of the pandemic. Overall,

analytic scores remained relatively similar for both providers and patrons,

with small changes in between periods (less than 4% change for both user

groups). When comparing scores between patron and provider chats, the Analytic

score was considerably higher for providers, indicating the prevalent use of

formal language by AskAway librarians.

Clout was consistently high for provider responses, with a 2.38% decrease

in the main pandemic stage, and a return to near pre-pandemic scores in the

late pandemic stage. For patron chats, even though a slight increase in clout

occurred over time, the levels remained low throughout all phases. These

numbers indicate that the language used by providers translates to higher

status, confidence, or leadership when compared to patron chats and that rates

did not change substantially during the pandemic.

Levels of authenticity were consistently low for provider chats in relation

to patron chats, and these levels decreased as the pandemic progressed.

Authenticity was high for patron chats, with levels consistently above 50% and

a slight increase during the pandemic. For provider chats, a more pronounced

decrease in authenticity occurred.

Both providers and patrons had positive emotional tone (scores consistently

higher than 50), but patrons had higher positive language than providers both

before and during the pandemic. An inverse trend was observed: while positive

language in provider chats declined during the pandemic (5.78% decline from

pre-pandemic levels and 3,84% decline between pandemic phases), scores for

patron chats had a small increase (less than 3% between pre-pandemic and

pandemic levels).

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the type and substance of chat reference

questions in an effort to understand a vital aspect of

academic library services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Researcher expectations

were that the type of questions would differ, in large part because the

experience of providing only virtual services seemed so different. However, similar to Hervieux (2021), our expectations are not

supported by the data. By examining AskAway transcripts and metadata, we found

homogenous results which demonstrated more consistency than difference in the

types of questions asked.

The use of Voyant Tools to explore patterns and interpret meaning in the

transcripts focused on the patron transcripts. When examining word frequency

over the pandemic timeline, the numbers indicate remarkable consistency in the

words used by patrons over time. Despite all of the

social and economic impacts of the pandemic, the shift to online-only classes,

and the closures of our physical libraries, this snapshot captured in the word

cloud figures depict the overwhelming use of AskAway for library-specific

questions that focus on research involving citation and locating and accessing

sources of information. Analysis using the Terms Berry feature duplicates the

Cirrus results, and the Trends tool did not prove insightful with the

transcripts.

LIWC shows a slight increase in analytic scores in the late pandemic which

might be correlated with increased use of pre-scripted language as a provider

strategy to deal with the increased volume on AskAway. This would also explain

declining rates in the authenticity dimension as pre-scripted language is

considered less authentic in LIWC. Though it is difficult to confirm exactly

why this is the case without qualitatively examining more closely the

interactions between providers and patrons, it is possible that certain

patterns in provider messages and scripts, such as higher use of articles, can

indicate higher analytic thinking and formality (Jordan et al., 2019). Analytic

scores of patron responses had more fluctuation between phases than those of

providers, However, similar scores in the pre and late periods suggest that the

main pandemic period may have in fact been a bit of an anomaly.

As observed by Kacewicz et al. (2014), the use of first-person plural

pronouns and an "outer-focus" language correspond with higher scores

in the LIWC clout dimension, and this might serve as a potential explanation

for the large discrepancy between provider and patron chats. For example,

several AskAway scripts use the pronoun "we" as part of their

composition, particularly the script used at the end of a chat, so the use of

plural personal pronouns may be contributing to higher provider scores in this

category, as opposed to other types of words that correlate to higher

confidence or social status. Regardless, levels of clout did not change

considerably during the pandemic, with changes to percentages remaining lower

than 3% for both patron and provider chats.

The decrease in the LIWC authenticity dimension for providers in the main

and late pandemic may again be associated with increased use of pre-scripted

messages, which tend to be formulated using neutral language and with higher

use of third-person pronouns. Since high authenticity is correlated with use of

first- and third-person singular pronouns (I, he, she), as described by

Kalichman & Smyth (2021), the increase of pre-scripted language that does

not match those characteristics can help explain the low scores for providers

and the differences when compared to patron chats. We can infer from these

numbers that patrons use more spontaneous language when compared to providers,

and that levels of spontaneity for patrons have not changed substantially

during the pandemic.

The difference in emotional tone scores between patron and provider chats

may be explained by certain patterns in provider responses and in how some

AskAway pre-formatted scripts are written. For example, the word 'lost' is

assigned to a negative emotional category in the LIWC dictionary. It also

happens to be part of a script used to check if patrons are still online after

a period of inactivity (Check in - lost script).

Coincidentally, “lost” was the negative word that appeared most frequently in

provider chats before and during the pandemic. Similarly, “worries” also had

high frequency in provider chats, but this word appears to be part of the

expression “'no worries,” an alternative to “you’re welcome.” This suggests

that emotional tone should be viewed with caution in this dataset, as

individual words may not accurately represent the actual tone of a chat. The

changes observed may be associated with the higher frequency of certain words

due to increased number of chats, rather than a substantive change in emotional

tone.

The main finding of consistent patron questions from

April 2020 - August 2021 has important implications for academic library

service provision and future planning. First, consistency in the question types

points to similar patron expectations for chat interactions, regardless of

class format and library building operations. Second, consistency in the

question types, despite the large increase in volume, points to a need for

flexible staffing responses in times of disruption or closure with sufficient

training to respond to research, citation, and a broad scope of library service

questions. Third, our findings have implications for staff training and

expectation management in times of disruption, whether planned or unexpected.

While we know that patrons' lives were upended during the pandemic, what they

expected of their academic libraries, at least as evidenced through chat

interactions, did not change. Future studies that compare patron expectations

with patron behavior, in times of both normalcy and disruption, would further

bolster this argument.

Limitations

Finally, as there are serious limitations to evaluating chat using

quantitative methods alone, due to the fragmented nature of chat interactions,

and because the volume of consortia chat does not easily lend itself to

qualitative analysis, an improvement in the nuance of tags applied by providers

would assist future assessment of the value of chat. As chat is poised to

continue as an important element within the academic library service ecosystem,

additional nuance in facilitating quantitative assessment of all reference

services would be a welcome improvement.

Conclusion

This article reports on the analysis of over 70,000 chat transcripts from a

diverse set of post-secondary institutions across British Columbia and the

Yukon and finds that, despite a significant increase in volume during the

pandemic, question types were remarkably consistent with those asked prior to

the pandemic. The professional literature has long advised that academic

libraries devote more attention to virtual services (Francoeur, 2001) but

closing the physical operations of libraries during the pandemic significantly

altered the urgency of this call (Radford et al., 2021). De Groote and Scoulas

(2021) utilized a multi-method approach to understand the impact of COVID-19 on

academic library use and found ongoing value for patrons in virtual service

offerings. The insights offered in this paper lend confidence in articulating

patron needs for chat reference as more than a supplemental service, but rather

a cornerstone of service provision, during both stable and uncertain times.

Echoing the findings of Mawhinney and Hervieux (2022), this paper also provides

support to the argument that the questions asked by chat patrons are complex,

with the largest segment of our dataset tagged as research in focus.

Author

Contributions

Barbara Sobol: Conceptualization, Formal

analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing -

original draft Aline Goncalves: Formal analysis, Methodology,

Visualization, Writing - original draft Mathew Vis-Dunbar: Methodology,

Visualization, Writing – review & editing Sajni Lacey: Literature

review, Writing - review & editing Shannon Moist: Writing - review

& editing Leanna Jantzi: Writing – original draft Aditi Gupta:

Analysis, Writing – review & editing Jessica Mussell: Methodology,

Writing - review & editing Patricia L. Foster: Literature review,

Writing - original draft Kathleen James: Literature review, Writing -

review & editing. We would also like to acknowledge Cristen Polley at BC

ELN for facilitating access to the data.

References

AskAway. (2022). Tags. https://askaway.org/staff/tags

BC Stats. (2018). College regions:

Detailed wall map. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/data/geographic/land-use/administrative-boundaries/college-regions/map_wall_college_regions_2018nov18.pdf

British Columbia Electronic Library Network. (2021). AskAway actions and achievements 2021 [Accessible version]. https://bceln.ca/sites/default/files/reports/AA_Actions_Achievements_2021_Accessible.pdf

British Columbia Electronic Library Network. (2022a). Participating institutions. https://bceln.ca/services/learning-support/askaway/participating-institutions

British Columbia Electronic Library Network. (2022b). Partner libraries: FTE information. https://www.bceln.ca/partner-libraries/fte

Chen, X., & Wang, H. (2019). Automated chat transcript analysis using

topic modeling for library reference services. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology,

56(1), 368-371. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.31

De Groote, S. and Scoulas, J.M. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on the use of

the academic library. Reference Services

Review, 49(3/4), 281-301. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-07-2021-0043

Francoeur, S. (2001). An analytical survey of chat reference services. Reference Services Review, 29(3),

189-204. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320110399547

Grabarek Roper, K., & Sobel, K. (2012). Anonymity versus perceived

patron identity in virtual reference transcripts. Public Services Quarterly, 8(4), 297-315. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228959.2012.730396

Graewingholt, M., Coslett, C., Cornforth, J., Palmquist, D., Greene, C.R.,

& Karkhoff, E. (2022). Chatting into the void: Scaling and assessing chat

reference services for effectiveness. In M. Chakraborty, S. Harlow, & H.

Moorefield-Lang (Eds.), Sustainable

online library services and resources: Learning from the pandemic (pp.

19-34). Libraries Unlimited.

Harlow, S. (2021). Beyond reference data: A qualitative analysis of nursing

library chats to improve research health science services. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 16(1), 46-59. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip29828

Hervieux, S. (2021). Is the library open? How the pandemic has changed the

provision of virtual reference services. Reference

Services Review, 49(3/4), 267–280. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-04-2021-0014

Jordan, K. N., Sterling, J., Pennebaker, J. W., & Boyd, R. L. (2019).

Examining long-term trends in politics and culture through language of

political leaders and cultural institutions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(9), 3476–3481. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1811987116

Kacewicz, E., Pennebaker, J. W., Davis, M., Jeon, M., & Graesser, A. C.

(2014). Pronoun use reflects standings in social hierarchies. Journal of Language and Social Psychology,

33(2), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X13502654

Kalichman, S. C., & Smyth, J. M. (2021). “And you don’t like, don’t

like the way I talk”: Authenticity in the language of Bruce Springsteen. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and

the Arts. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000402

Kathuria, S. (2021). Library support in times of crisis: An analysis of

chat transcripts during COVID. Internet

Reference Services Quarterly, 25(3), 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875301.2021.1960669

Lapidus, M. (2022). Reinventing virtual reference services during a period

of crisis: Decisions that help us move forward. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 41(1), 41-53. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2022.2021033

LIWC. (n.d.). Understanding LIWC

summary measures. https://www.liwc.app/help/liwc#Summary-Measures

Logan, J. & Barrett, K. (2018). How important is communication style in

chat reference? Internet Reference

Services Quarterly, 23(1-2), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875301.2019.1628157

Logan, J., Barrett, K., & Pagotto, S. (2019). Dissatisfaction in chat

reference users: A transcript analysis study. College & Research Libraries, 80(7), 925–944.

Mawhinney, T., & Hervieux, S. (2022). Dissonance between perceptions

and use of virtual reference methods.

College & Research Libraries, 83(3), 503. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.83.3.503

Mungin, M. (2017). Stats don’t tell the whole story: Using qualitative data

analysis of chat reference transcripts to assess and improve services. Journal of Library & Information Services

in Distance Learning, 11(1/2), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2016.1223965

Oracle. (2022). Java documentation:

About the BreakIterator class. https://docs.oracle.com/javase/tutorial/i18n/text/about.html

Ozeran, M., & Martin, P. (2019). “Good night, good day, good luck”:

Applying topic modeling to chat reference transcripts. Information Technology and Libraries, 38(2), 59-67. https://doi.org/10.6017/ital.v38i2.10921

Radford, M., Costello, L., & Montague, K. (2021). Surging virtual

reference services: COVID-19 a game changer. College & Research Libraries News, 82(3), 106–113. https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.82.3.106

Reference and User Services Association. (2017). Guidelines for implementing and maintaining virtual reference services.

https://www.ala.org/rusa/sites/ala.org.rusa/files/content/GuidelinesVirtualReference_2017.pdf

Sharma, A., Barrett, K., & Stapelfeldt, K. (2022). Natural language

processing for virtual reference analysis. Evidence

Based Library and Information Practice, 17(1),

78-93. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip30014

Schiller, S. Z. (2016). CHAT for chat: Mediated learning in online chat

virtual reference service. Computers in

Human Behavior, 65, 651-665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.06.053

Sinclair, S. & Rockwell, G. (2022). Voyant

Tools (Version 2.6.1). [Text analysis app]. https://voyant-tools.org/

Sloan, B. (1998). Electronic reference services: Some suggested guidelines. Reference and User Services Quarterly, 38(1),

77-81.

Smith, M., Conte, J., & Guss, S. (2016). Understanding academic

patrons’ data needs through virtual reference transcripts: Preliminary findings

from New York University Libraries. IASSIST

Quarterly, 40(1), 20–26. https://doi.org/10.29173/iq624

Statistics Canada. (2020, May 12). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on

postsecondary students. The Daily. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200512/dq200512a-eng.htm

Tausczik, Y. R., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2010). The psychological meaning

of words: LIWC and computerized text analysis methods. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 29(1), 24–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X09351676

Walker, J. & Coleman, J. (2021). Using machine learning to predict chat

difficulty. College & Research

Libraries 82(4), 683-707. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.82.5.683

Wang, Y. (2022). Using machine learning and natural language processing to

analyze library chat reference transcripts. Information

Technology and Libraries, 41(3), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.6017/ital.v41i3.14967

Watson, A. P. (2023). Pandemic chat: A comparison of pandemic-era and

pre-pandemic online chat questions at the University of Mississippi Libraries. Internet Reference Services Quarterly, 27(1), 25-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875301.2022.2117757

World Health Organization. (2023). Coronavirus

disease: COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.who.int/europe/emergencies/situations/covid-19