Research Article

Video Game Equipment Loss and

Durability in a Circulating Academic Collection

Diane Robson

Games and Education Librarian

University of North Texas Libraries

Denton, Texas, United States of

America

Email: diane.robson@unt.edu

Sarah Bryant

Reference and Instruction

Librarian

Western Wyoming Community

College

Rock Springs, Wyoming, United

States of America

Email: sbryant@westernwyoming.edu

Catherine Sassen

Principal Catalogue Librarian

University of North Texas Libraries

Denton, Texas, United States of America

Email: catherine.sassen@unt.edu

Received: 4 Jan. 2023 Accepted: 17 May 2023

![]() 2023 Robson, Bryant, and Sassen. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2023 Robson, Bryant, and Sassen. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30294

Abstract

Objective – This article reviewed twelve

years of circulation data related to loss and damage of video game equipment,

specifically consoles, game controllers, and gaming peripherals such as

steering wheels, virtual reality headsets, and joysticks in an academic library

collection.

Methods – The authors analyzed data gathered from game equipment

bibliographic and item records. Only data related to the console system, game

controllers, and peripherals such as steering wheels, virtual reality headsets,

and joysticks were evaluated for rate of circulation, loss, and damage. Cables

and bags were not evaluated because the replacement cost for these items is

negligible when considering long-term budgeting and maintenance of a game

collection.

Results – The majority of

video game equipment can be circulated without unsustainable loss or damage.

The library has been able to continue circulating video game equipment without

undue replacement costs or loss of access for its patrons.

Conclusion – Although equipment will

occasionally break or be lost, libraries should not let this unduly affect

consideration when starting a video game collection.

Introduction

Although some academic libraries are starting to add video game collections

to support research and recreation, there still seems to be a reluctance to

collect items outside the norm. These items do require different skill sets to

manage but libraries already deal with materials and software that require some

specialization. Although loss and damage for these items should be a concern,

the costs related to collecting game equipment are no more exorbitant than

other library technology.

Video games are a big part of our culture with 66% of Americans playing

video games weekly; 83% of players begin new relationships and develop

friendships through play (Entertainment Software Association, 2022). In

addition to recreation, these collections serve scholars in their study and

creation of games. Libraries should not let concerns about loss, damage, and

other difficulties related to these materials hinder adding a collection that

can supplement recreation, engagement, innovation, and scholarship in the

library.

The University of North Texas (UNT) Media Library has been circulating a

growing video game collection for over ten years. This article provides details

about the game equipment in this collection. Game consoles and controllers are

some of the biggest costs for a collection. This research will examine the

durability, lifespan, loss, management, and maintenance of these items. This

evidence will be useful to libraries considering the viability and costs of

establishing, expanding, or managing a collection in their own library.

Given the limited life span of video game equipment and the expense of

replacement components, managers of video game collections stand to benefit

from detailed research on equipment durability in a circulating collection.

However, none of the studies found in the literature review presented such

research. The present article is designed to fill this research gap.

Literature Review

Administering an academic library video game collection involves a variety

of challenges ranging from changes in game design, game technology, and

purchasing arrangements to evolving opportunities in support of educational and

recreational needs on campus. As Robson et al. (2020) noted, “Managing

challenges related to content, access, equipment, space, and outreach, with the

goal of effectively supporting students, staff, and faculty can be exasperating

but is also exciting and rewarding” (p. 3).

Although most of these challenges have been covered extensively in the

literature, libraries should devote more attention to equipment, considering

its crucial role in the successful operation of a video game collection. The

scope of this literature review is limited to the maintenance and durability of

video game equipment in libraries. This review draws on research reports,

feature articles, and publications providing guidance on library video game

collection management. For more information about academic library video game

collections in the contexts of collection development, library instruction,

outreach, cataloguing, assessment, gaming spaces, and virtual and augmented

reality, see Robson et al. (2020).

Equipment Durability and Longevity

Video game components inevitably wear out with continued use. A library may

decide to purchase extra components as backups to save time in locating them

when replacements are needed (Williams & Chimato, 2008). Other options may

include repairing equipment and using 3D printing to create replacement parts

(Panuncial, 2019).

Equipment compatibility is a concern in video game collections because

games that can be played on older consoles may not necessarily be played on

newer consoles (Cross et al., 2015). A library may collect legacy consoles to

mitigate this situation. It is possible to find older equipment on eBay or in

pawn shops (Robbins, 2016); however, the library should prohibit the

circulation of these consoles, considering the historic importance of equipment

that is no longer in production (Robbins, 2016). The library also may restrict

access to games on cartridges because of preservation concerns. A strategy to

provide access to older games while preserving legacy consoles would be to use

video game emulators (Cross et al., 2015).

Care and Handling

The condition of a video game is influenced by the environment in which it

is housed and the way it is handled (Byers, 2003; Leblanc, 2021). Environmental

conditions include temperature, humidity, moisture, solvents, light exposure,

dust, debris, and smoke. Handling effects include scratches, smudges, marking,

labels, and wear. Byers (2003) and McDonough et al. (2010) provide guidance on

mitigating these factors.

Circulation policies and practices affect the integrity of video game

collections (Buller, 2017; Goodridge & Rohweder, 2021). Libraries should

develop policies covering lending and use issues as well as replacement fees to

document expectations for users. After each circulation, staff should ensure

that all equipment components have been returned. They should check discs for

damage and clean them. Other post-circulation tasks may include verifying that

consoles function properly and removing any data left by players. Circulating

collections must have appropriate physical processing to protect the items and

facilitate the check-in process (Robson et al., 2017).

Aims

In this article, we discuss the durability and loss of video game consoles,

controllers, and peripherals in an academic video game collection over twelve

years, as well as management and maintenance decisions needed to sustain

equipment and increase its longevity. Can an academic library sustain a video

game collection, or will loss and damage be unsustainable?

Durability is a consideration for all purchases but is particularly

important for non-consumable items. Video game equipment will be set up and

taken down, held for hours in sometimes sweaty hands, and dropped. There is no

standard metric for game equipment durability in a library setting. Use

determines longevity and use varies greatly between the user and the game

played. The ability to repair wear and tear is also a consideration. There is

no easy answer and often budgets will determine each library’s ability to

sustain this type of collection.

Loss, defined as items missing or not returned, is another question

entirely. Academic libraries conducting inventory projects have reported a

variety of loss rates. For example, an inventory conducted at the University of

Mississippi Libraries found losses ranging from 9% to 16%; this library set its

acceptable loss rate at 4% (Greenwood, 2013). A library inventory at Seton Hall

University in the 1990s estimated a 14% missing rate for their collection with

no desired loss rate stated (Loesch, 2011).

The acceptable rate of loss is specific to each collection, its size, and

user needs. Each library will need to determine if their loss rate hinders

research, instruction, and play, and if their budget can sustain a game

collection through such losses. This research does not intend to determine a

universal rate of loss for libraries with game collections but will examine

current loss rates at the UNT Media Library.

Methods

We limited the scope of data to consoles, controllers, and game peripherals

such as Wii pads and steering wheels. This research study focused on this

equipment because the replacement costs of a console, controller, or peripheral

are much higher than plugs, cables, or headphones. The durability of these

materials is important when considering the long-term costs of maintaining a

game collection.

We collected data from bibliographic and circulation records for 497

consoles, controllers, and peripherals. These data included circulation

statistics generated automatically and notes about loss and damage from

December 1, 2009, through the data capture on February 1, 2022. Information in

library item records included the item create date, last check-in (return

date), total checkout, renewals, and status. The lifespan was

calculated from the item record create date and last check-in

date for lost/paid/damaged items. The available lifespan was calculated with

the item record create date and the data capture date (February 1,

2022). The total circulation was the sum of the total checkout and renewals

values. The status included available, lost and paid, lost, billed,

on search, missing, and discarded. The statuses for lost and paid, lost,

billed, on search, and missing were all bundled into Billed/Lost/Paid because

these items were not returned to the library. Discarded items were either those

returned with either general wear and tear or consoles damaged by patrons.

Notes included content added to the bibliographic records for non-consumable

items, documenting purchases and any loss or damage that happened over an

item's lifetime in the library, as well as the circulation count at the time of

discard. Legacy collection items were not included in the durability values for

this review. The Legacy collection consists of older equipment that is

considered obsolete or difficult to replace.

Overview

The UNT Media Library is one of four libraries that serve the educational

and research needs of about 48,600 faculty, staff, and students across two

campuses in Denton, Texas. The Media Library houses non-print, audiovisual,

tabletop, and video game collections. The video game collection began in 2009

with a small grant and has grown to include services and collections to support

student recreation, research, and coursework. This collection is used for

student and staff programming, coursework, and university game-related

initiatives such as esports and a game studies and design degree.

The Media Library is a collaborative space that encourages engagement

around play. In 2018–2019[1]

the Media Library served 104,890 patrons at its circulation desk and in its

spaces. There were 12,427 PC reservations and 10,456 game station reservations.

Game-related equipment was checked out 7,427 times. Before 2009, this space was

primarily a quiet space for viewing audiovisual reserves. As audiovisual

collections moved online, viewing carrels were no longer needed so their space

needs decreased. This allowed the game space to increase to include in-house

reservable space with 10 console stations, 22 PCs, virtual reality devices, and

tables for gaming and play. Most of the collection circulates out to faculty,

staff, and students with a few exceptions for older, costly, or larger devices.

In late 2009, the video game and console collection consisted of modern

consoles. It included a Nintendo Wii, a PlayStation 3, an Xbox 360, controllers

for each console, and a few peripherals such as guitars, a keyboard, and a

steering wheel. Today the collection includes modern consoles such as the Xbox

Series X and PlayStation 5, as well as older legacy consoles and equipment such

as the Wii, PlayStation 3, and Xbox 360.

Obsolescence is a concern with library collections. New consoles are

released about every three to five years which brings obsolescence into

consideration much earlier than some other library materials.

The Media Library embraced this cycle of renewal with its film collection

and decided to do the same with the game collection. Not only have library

staff developed procedures to keep our collection of seventh-generation

consoles (Wii, Xbox 360, PS3) in the collection; we have reached even further

into the past to develop a legacy collection of older equipment to support

research and instruction. The game collection now houses equipment that spans

the second console generation (1976–1992; Gallagher & Park, 2002) to modern

devices in the ninth console generation (2020–present).

The equipment in this collection is curated to meet the needs of faculty,

staff, and students. Several different budgets are used to purchase and

maintain the collection. All video game content, i.e., discs and cartridges, is

purchased with the general materials budget. A yearly game equipment budget is

used to purchase new equipment and legacy items. The library accepts gifts that

have helped a collection of older content and consoles grow without additional

costs. Smaller items, such as batteries, bags, and cleaners, needed to maintain

the longevity of the collection are purchased through a supply budget.

The library’s definition of a non-consumable durable item vs. a consumable

item has shifted as staff learned how to manage this type of collection, with

the budget reflecting the need to purchase some items yearly because of wear

and tear. Consumables such as batteries, bags, cables, and headphones degrade

much quicker than non-consumable items such as console systems, controllers,

and peripherals. Each year new purchases, replacements, and maintenance are

considered when determining purchases.

A video game collection, like any new collection, does cost money, and

library staff had fears about unsustainable loss. Early procedures played to

these fears by requiring patrons to sign extra documentation reiterating their

responsibilities at each checkout. These additional procedures added time to

check out and did not minimize loss, so these procedures were relaxed to a

simple checkout/check-in in the library system in 2014. Details in the

circulation record are sufficient to note responsibility for materials.

Damage is another consideration, but a video game collection is much like

any other collection. There will be damage and parts will break. This means

understanding that some parts do break and the library will need to expand the

idea of what a consumable is to include additional easily replaced items like

cables and headphones. The library’s long-term goal is to mitigate

unsustainable loss and damage with proper procedures and maintenance.

Collection

The UNT Media Library includes a collection of circulating content,

consoles, and peripherals that circulate outside the library to faculty, staff,

and students. The reserve collection circulates in-house and supports play in

library game spaces. The Legacy Collection, which includes older consoles from

generations two through six, is used in-house for research and instruction

only. The game collection continues to grow across generations with consoles

from the eighth generation, specifically the Nintendo Switch and PlayStation 4,

still in high demand.

This collection circulates like most other physical items in a library.

Students can check out three items for 3 days. Faculty and staff can check out

10 items for 7 days. Circulating equipment may be placed on hold. Faculty,

staff, and official student groups are allowed to book materials. A booking

holds the item for a specific date and ensures items are available for class or

group events.

Consoles

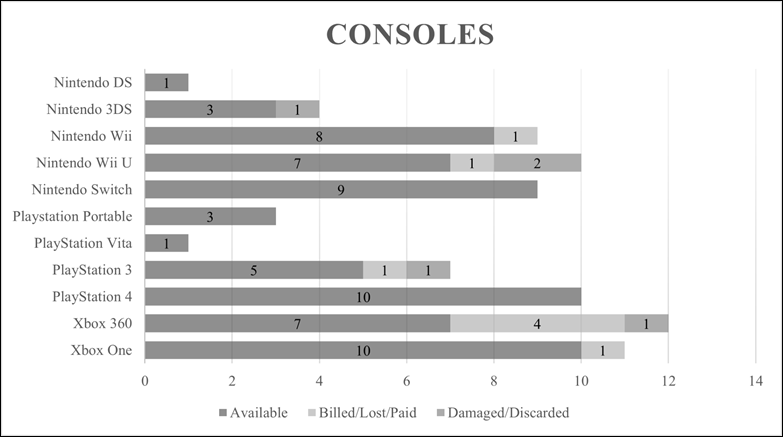

The overall data displayed in Figure 1 show that the circulating console

collection has not suffered unsustainable loss or breakage. Over the life of

this collection, 6% of consoles were discarded because of damage. None of this

damage was intentional; it was merely wear and tear. No specific console system

suffered more damage than another.

Analysis shows 10% of consoles were lost, paid, or billed. Although this

loss rate is fairly high, it has not hindered the library’s ability to provide

equipment to access content. Seen another way, the library only lost one copy

out of the four available for the Nintendo 3DS.

Unlike a book on an open shelf, these items are held more securely when not

checked out, so loss is often tied to a specific patron and the library has a

chance of recovering the cost of the item. Most losses are due to students

withdrawing from school while an item is in their possession. Sudden closures

from COVID-19 increased the recent loss rate, as students who had items did not

return to university or re-enroll.

Figure 1

Cumulative total for consoles from 2010–2022 (available, billed/lost/paid,

damaged/discarded). There is a slight degree of uncertainty in data related to

the difference in notes added to the bibliographic records related to loss and

damage.

Table 1

Median Values and Statistics for Consoles (2010–2022)

|

Consoles |

|||||||

|

|

Median Lifespan/ Years |

Median Circulation |

Oldest |

Highest Circulation |

Loss |

Damage |

Total Consoles |

|

Nintendo |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3DS |

3 |

78 |

6 |

184 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

|

DS |

10 |

237 |

10 |

237 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

Switch |

3 |

59 |

4 |

576 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

|

Wii |

4 |

46 |

11 |

230 |

1 |

0 |

9 |

|

Wii U |

4 |

24 |

7 |

223 |

1 |

2 |

10 |

|

PlayStation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PlayStation Vita |

6 |

101 |

6 |

101 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

PlayStation Portable |

6 |

43 |

9 |

122 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

|

PlayStation 3 |

6 |

233 |

11 |

364 |

1 |

1 |

7 |

|

PlayStation 4 |

5 |

45 |

6 |

293 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

|

Xbox |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Xbox 360 |

3 |

61 |

10 |

305 |

4 |

1 |

12 |

|

Xbox One |

6 |

162 |

6 |

278 |

1 |

0 |

11 |

A closer look at the data for circulating consoles, as illustrated in Table

1, shows how durable some systems have been over this time period, with some

consoles circulating hundreds of times outside the library. Game console system

durability exceeded early expectations. The median age of the circulating

console collection is five years. This median age reflects the addition of

newer generations of consoles, but also new-to-the-library older consoles. The

median circulation total across the circulating console collection is 61.

Console system cases have been sturdy with little actual physical breakage.

Most of the items discarded as damaged had software or system failures.

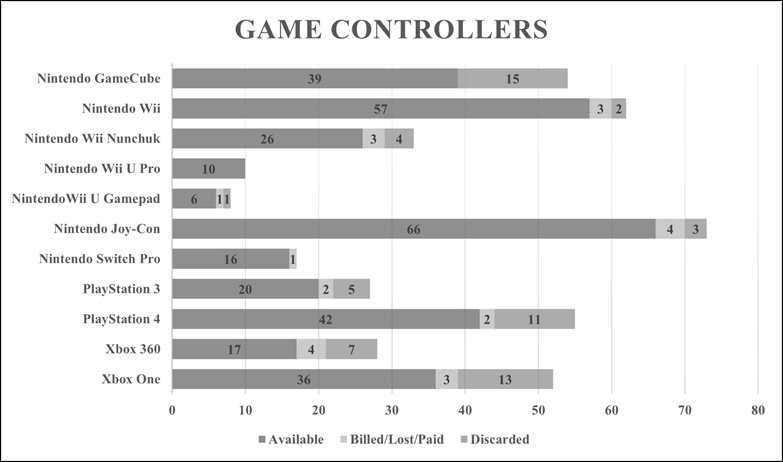

Game Controllers

Game controllers are also more durable than first predicted, with a

breakage rate of 14% and a loss rate of 5%, as illustrated in Figure 2. These

data are skewed because four off-brand GameCube controllers, which were

purchased when budgets were tight, broke almost immediately. The library has

learned that breakage is often very early in the controller’s life and paying

the price up front for a name-brand controller is the best option for

longevity.

Figure 2

Cumulative total for controllers from 2010–2022 (available,

billed/lost/paid, damaged/discarded). There is a slight degree of uncertainty

in data related to the difference in notes added to the bibliographic records

related to loss and damage.

Each console circulates with two game controllers in the console bag.

Additional controllers are available in their own bags. A closer look at

circulating controllers and video game peripherals, as illustrated in Table 2,

shows how durable some of these items have been with several controllers

circulating over 1,000 times. Damage is higher for modern controllers,

specifically the Joy-Con, PS4, and Xbox One.

Table 2

Median Values and Statistics for Controllers (2010–2022)

|

Game Controllers |

|||||||

|

|

Median Lifespan/ Years |

Median Circulation |

Oldest |

Highest Circulation |

Loss |

Damage |

Total Controllers |

|

Nintendo |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

GameCube |

3 |

225 |

9 |

1,030 |

0 |

15 |

54 |

|

Wii |

4 |

129 |

12 |

1,148 |

3 |

2 |

62 |

|

Wii Nunchuk |

6 |

70 |

11 |

267 |

3 |

4 |

33 |

|

Wii U Pro |

4 |

140 |

4 |

205 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

|

Wii U Gamepad |

5 |

394 |

7 |

963 |

1 |

1 |

8 |

|

Joy-Con |

1 |

13 |

4 |

248 |

4 |

3 |

73 |

|

Switch Pro |

1 |

7 |

3 |

211 |

1 |

0 |

17 |

|

PlayStation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PlayStation 3 |

6 |

77 |

11 |

1,130 |

2 |

5 |

27 |

|

PlayStation 4 |

4 |

177 |

6 |

580 |

2 |

11 |

55 |

|

Xbox |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Xbox 360 |

6 |

183 |

11 |

1,232 |

4 |

7 |

28 |

|

Xbox One |

4 |

110 |

6 |

329 |

2 |

11 |

52 |

Peripherals

The library also circulates peripherals. Most of the peripherals listed in

Table 3 circulate inside and outside of the library. Virtual reality headsets

are in-house checkouts for use within the library. The Guitar Hero and Rockband

sets and their accessories were the one peripheral type pulled from circulation

outside of the library because of damage. These sets are still used during

special events but are no longer available for regular use.

Table 3

Median Values and Statistics for Video Game Peripherals (2010–2022)

|

Video Game Peripherals |

||||||

|

|

Median Lifespan/ Years |

Median Circulation |

Oldest |

Highest Circulation |

Loss |

Damage |

|

Peripherals |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wii Wheel |

11 |

65 |

11 |

77 |

0 |

0 |

|

Wii Perfect Shot |

5 |

1 |

6 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

|

Wii Balance Board |

6 |

32 |

9 |

59 |

0 |

0 |

|

Wii Dance Pad |

9 |

36 |

11 |

55 |

0 |

0 |

|

Nintendo Zapper |

3 |

5 |

3 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

|

Switch Ring Fit |

1 |

4 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

|

PS3 Move camera |

10 |

29 |

10 |

57 |

0 |

0 |

|

PS4 VR headset |

4 |

151 |

4 |

249 |

0 |

0 |

|

HTC Vive Pro |

4 |

290 |

4 |

290 |

0 |

0 |

|

PS3 Rockband |

7 |

59 |

7 |

65 |

0 |

1 |

|

PS3 Guitar Hero |

7 |

10 |

7 |

32 |

0 |

0 |

|

Xbox 360 Guitar Hero |

8 |

13 |

8 |

45 |

0 |

1 |

|

Xbox 360 Rockband |

8 |

13 |

8 |

13 |

0 |

1 |

|

Wii Guitar Hero |

1 |

14 |

1 |

14 |

0 |

1 |

Legacy Equipment

One way that the library has ensured equipment is available for older

content is by developing a Legacy Collection. Over the past 4 years this

collection has been curated to support research and instruction as shown in

Table 4. In the future when production of a console system ceases, two copies

will be pulled from circulation and added to the Legacy Collection, which is

housed in media cabinets. Consoles are also purchased to supplement this

collection to support play of historical formats.

Table 4

List of Legacy Consoles

|

Atari 2600 Sega Master System Sega Saturn Sony PlayStation Nintendo 64 Sega Dreamcast |

Sony PlayStation 2 Nintendo GameCube Microsoft Xbox Sony PlayStation 3 Microsoft Xbox 360 Nintendo Wii U Sony PlayStation 4 |

Consoles in the Legacy Collection do not circulate outside of the library.

Therefore, when circulating items enter this collection, the metrics for

durability change. Once an item makes it into this collection, circulation

count is no longer a metric for determining usage. Usage is determined by

tracking class attendance for those using the collections to supplement

coursework and individual research reservations.

Durability is no longer a leading factor for items in the Legacy

Collection. The goal shifts to maintenance to increase longevity. As this

collection is only 4 years old, processes and procedures related to its

management and maintenance are still evolving. At this time, one console, a

Sega Master System, suffered an electronic failure, and another, a Nintendo

Entertainment System, no longer produces sound. These failures are a bigger

concern for this collection, but time will tell if it is sustainable as an

educational resource.

Management and Maintenance

The statistics above show that a game collection can be

circulated without unsustainable loss or breakage. One of the biggest hurdles

related to beginning this type of collection is overcoming undue fears about

equipment loss in relation to other library collections. Developing a

management and maintenance plan to mitigate loss and breakage can help

positively persuade those making decisions related to these types of

collection. Over the past ten years the Media Library has modified its

management, cleaning, and maintenance plans to increase the longevity of this

collection.

Collection Management

Circulating video game equipment and its peripherals are housed in closed

stacks or behind the circulation desk on reserve. All of the equipment in the

Media Library is catalogued for an accurate inventory, but not all of it is

visible to patrons. Consoles are processed with an item record for each

included item (e.g., HDMI cables, power cables, controllers). Equipment is

circulated in a barcoded bag. The bag item record is what displays to the

patron in the library system and is used to place holds, bookings, and manage

the equipment as a whole. Each console circulates with two controllers and

batteries. Individual controllers and other game-related peripherals are also

available for checkout in their own processed bags.

At checkout, all item barcodes are scanned to the patron’s account. At

check-in, items are checked in and the service desk staff ensures that

equipment is cleaned and organized neatly in the bag. Batteries circulate in

their own barcoded box and are removed from controllers and bags at check-in.

The Media Library uses rechargeable batteries.

In-house non-circulating equipment and controllers are also catalogued.

In-house materials include consoles, controllers, virtual reality devices, and

gaming peripherals such as joysticks, steering wheels, and drum kits. In-house

items are on reserve behind the front desk. They are checked in and out like

outside circulating items but are not bagged.

These in-house items are used in our gaming space. This space includes 10

game stations and 22 gaming PCs. All of these stations are reservable using

Springshare’s LibCal for up to 4 hours a day. Entire spaces can be reserved by

faculty, staff, and student groups for classes and engagement.

Each reservable game station includes at least two cable-locked consoles

with access to the internet and online game platforms such as PlayStation

Network, Xbox Game Pass, and Nintendo. Internet access is locked to each

console’s MAC address. Each station includes a high-definition television with

a switch selector for input control. Students can play their own digital

content or library-owned physical content. Play must be saved to the cloud both

to mitigate loss, as anyone can delete content on these stations, and to ease

console content space issues. Patrons are allowed to bring in their own

consoles, controllers, and peripherals but cannot access the internet through

ethernet on all outside devices besides the Switch console.

Cleaning and Maintenance

As the continuous use of gaming equipment grew, so did the need for

cleaning and maintenance. Consoles, controllers, peripherals, and headphones

are examined at check-in and cleaned. Items are wiped down and any microphone

covers are changed out. A deeper clean is done each month. Student staff

retrieve each console, wipe it down and check it for damage, and check the

circulation bag for damage or debris.

Circulating remotes are deep cleaned. Deep cleaning involves using a soft

pick to clean out any dirt in the crevices and a cotton swab to clean around

toggles and buttons with an alcohol solution. Any peeling barcodes or labels

are replaced at this time. Cables are wiped down and managed with rubber bands.

During the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, all equipment was quarantined

for a 3-day period between checkouts until the library bought a sanitizing

light station.

Broken items or devices with software issues are checked out to a Media

Library Problem Items patron record. Student staff record the problem onto

a problem item paper slip, attach the slip to the item, and place it into a

tray. Each item is double-checked by student staff for the noted issue and

resolved as needed. Problems might include consoles that need formatting or

updates, broken cables, controllers that do not respond or have drift, a part

that is missing, or an item record issue.

The addition of high-use GameCube controllers led to library repair

procedures for controllers. Repairs began simply with new joystick toggle caps

but now include replacing joysticks in the Joy-Con to mitigate drift and

replacing broken power jacks in handheld consoles. Many of the components in

modern consoles are easily replaceable. The library purchases kits and

screwdrivers to clean and repair most of our controllers. Select working parts

from broken controllers are kept to make other repairs. These parts include the

rubber button pads, triggers, toggles, and springs.

Proper maintenance is important. Not only does it help keep equipment clean

and working, but it also allows staff to take a closer look at equipment to

find problems before they become a bigger issue. Cleaning equipment and

performing simple repairs increases the longevity of circulating controllers.

Legacy Collection Maintenance

New equipment in Generation 7 and beyond, such as the Wii, PlayStation 3,

and Xbox 360, are maintained like the non-Legacy circulating collections. Older

equipment can require more maintenance. Equipment should be cleaned, but

consideration should be taken before applying any chemical processes to

brighten or renew the look. For example, a console that has changed color

because of smoke might look better if restored or whitened but this may make

the plastic brittle. A careful review of renewal processes should be done to

ensure that it will not decrease lifespan.

Older consoles, and the cartridge games that are played in them, have pins

that need care and cleaning. Metal pins corrode over time but are easily

cleaned with an alcohol solution and very fine grit sandpaper. The library uses

the 1UPcard cleaners on content cartridges and console pins before use. If a

warm breath is used to get a cartridge to play, cleaning with a cotton swab and

alcohol should be done before storing the item. Although older consoles are

very sturdy, maintenance should be done with care.

There are repair kits with more modern boards available for older consoles.

Care should be taken when repairing these older items. An old console case with

all new parts is more like an emulator than the original device. Emulators

mimic a console and can play old content but are generally not using technology

specific to the original, so play would differ. Each library’s needs can

dictate what types of repairs are acceptable for its equipment. If an older

console is not something a library wishes to support, there are emulators for

purchase that will play most older game cartridges as well as some preloaded

with retro games.

Conclusion

This study examined the sustainability of the consoles,

controllers, and peripherals in a video game collection in an academic library.

Prior to incorporating video games and their associated equipment into the

collection, there were concerns that such a collection could pose problems for

collection management; these issues included increased staff procedures needed

for circulation, the expense of replacing lost equipment, dealing with damage,

and obsolescence. Library staff continue to develop procedures to efficiently

manage, clean, and maintain these collections to decrease wear and tear in the

hopes that it increases longevity and reduces replacement costs. Over the

survey period of 12 years, there was indeed equipment loss and damage; however,

the library was still able to meet the needs of students, faculty, and

researchers and the cost of replacing or repairing the items was negligible. In

conclusion, the researchers believe that including circulating consoles in a

video game collection is a valued addition to a library that can supplement

programming, boost innovation, and support burgeoning scholarship without being

unsustainable.

Author Contributions

Diane Robson: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis,

Visualization, Writing – original draft (lead) Sarah Bryant: Data

curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing Catherine

Sassen: Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review &

editing

References

Buller, R. (2017). Lending video game consoles in an academic library. portal:

Libraries and the Academy, 17(2),

337–346. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2017.0020

Byers, F. R. (2003). Care and handling of CDs and DVDs: A guide for

librarians and archivists. Council on Library and Information Resources. https://doi.org/10.6028/nist.sp.500-252

Cross, E., Mould, D., & Smith, R. (2015). The protean challenge of game

collections at academic libraries. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 21(2), 129-145.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2015.1043467

Entertainment Software Association. (2022, June). 2022 essential facts about the video game industry. https://www.theesa.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/2022-Essential-Facts-About-the-Video-Game-Industry.pdf

Gallagher, S., & Park, S. H. (2002). Innovation and competition in

standard-based industries: A historical analysis of the US home video game

market. IEEE Transactions on Engineering

Management, 49(1), 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1109/17.985749

Goodridge, M., & Rohweder, M. J. (2021). Librarian's guide to games and gamers: From collection development to

advisory services. Libraries Unlimited.

Greenwood, J. T. (2013). Taking it to the stacks: An inventory project at

the University of Mississippi Libraries. Journal of Access Services, 10(2), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/15367967.2013.762266

LeBlanc, K. (2021). The quagmire of video game preservation. Information Today, 38(5), 16–17.

Loesch, M. F. (2011). Inventory redux: A twenty-first century adaptation. Technical

Services Quarterly, 28(3),

301–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317131.2011.571636

McDonough, J., Olendorf, R., Kirschenbaum, M., Kraus, K.,

Reside, D., Donahue, R., Phelps, A., Egert, C., Lowood, H., & Rojo, S.

(2010). Preserving virtual worlds: Final report. National Digital

Information Infrastructure and Preservation Program. http://hdl.handle.net/2142/17097

Panuncial, D. (2019). Librarians, start new game: How academic librarians

support videogame scholars. American

Libraries, 50(11/12), 42–45.

https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2019/11/01/librarians-start-new-game-videogame-collections/

Robbins, M. B. (2016). Invest in the classics. Library Journal, 141(13),

58. https://www.libraryjournal.com/story/invest-in-the-classics-games-gamers-gaming-august-2016

Robson, D., Parks, S., & Miller, E. D. (2017). Building game

collections in academic libraries: A case study at the University of North

Texas. In M. Robison & L. Shedd (Eds.), Audio recorders to zucchini seeds: Building a library of things (pp.

171–186). Libraries Unlimited.

Robson, D., Sassen, C., & Rodriguez, A. (2020). Advances in academic video game collections. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 46(6), 102233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102233

Williams, J. M., & Chimato, M. C. (2008). Gaming in D.H. Hill Library,

NC State University. In A. Harris & S. E. Rice (Eds.), Gaming in academic libraries: Collections,

marketing, and information literacy (pp. 66–75). Association of

College and Research Libraries.