Using Evidence in Practice

Engaging with Psychology Students to Find New Ways of Improving Behaviour in Libraries

Louise Dawson

Customer

Service Assistant

JB Priestley

Library

University of

Bradford

United

Kingdom

Email: l.dawson@bradford.ac.uk

Louise Phelan

Academic

Support Librarian for Psychology

JB Priestley

Library

University of

Bradford

United

Kingdom

Email: l.phelan@bradford.ac.uk

Received: 1 Aug.

2023 Accepted: 11 Oct.

2023

![]() 2023 Dawson and Phelan. This is an Open Access

article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use,

distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is

properly attributed, not used for commercial purposes, and, if transformed, the

resulting work is redistributed under the same or similar license to this one.

2023 Dawson and Phelan. This is an Open Access

article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use,

distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is

properly attributed, not used for commercial purposes, and, if transformed, the

resulting work is redistributed under the same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30446

Setting

In the period

following the pandemic, we observed that poor student behaviour was

increasingly becoming a problem in our library. We decided to take a novel

approach to try and discover new ways of encouraging positive use of the

university library using existing resources and ensuring the inclusion of

student voices to gather rich critically evaluated feedback to inform our

service improvements.

The

University of Bradford is a medium-sized university in Yorkshire, United

Kingdom. It is serviced by the JB Priestley Library, which is located centrally

on campus. The library facilities offer a range of study spaces from silent

study to group collaborative spaces. The library lacks a distinct separate

entrance, as it is not in a separate building.

Problem

Following the

full reopening of the library to normal service after the end of COVID-19

pandemic restrictions, staff noticed a significant deterioration in student

behaviour compared to pre-pandemic. Problems ranged from disruptive and

confrontational behaviour to vandalism of the building and contents. This had a

significant negative impact on the student experience for legitimate library

users and was unsustainable in terms of damage to facilities and on the

wellbeing of students and staff. Conversations with colleagues in other

institutions confirmed that these problems were not Bradford-specific.

Existing ways

of dealing with poor behaviour using signage about specific behaviours and

policies (e.g., food and drink, vandalism, and alcohol) had little impact. A

student behaviour group formed of library staff was created to consider

solutions. One suggestion was taking the problem to psychology students within

the university to gain a new perspective on understanding and addressing the

roots of these behaviours. This combined student perspectives with a critically

evaluated psychological grounding.

We wanted to

find new ways of improving the experience of students using the library for

legitimate study purposes in ways that could be implemented by staff and

without the need for expensive improvements, furniture replacement, or building

work. We also wanted to ensure that the student voice and perspective was

included in a constructive and novel way.

Evidence

We approached

an Associate Professor of Social Psychology, about the possibility of involving

students from the psychology department. The professor suggested that the

problem be introduced as a case study as part of an established team-based

learning session for a class of 25 master’s degree psychology students.

Team-based learning is an active learning method in which classroom sessions

are devoted to team problem-solving rather than lectures (Tweddell, 2020). Both

authors were then invited to attend the session to introduce the problem and

assess the ideas presented.

We provided

the following information and evidence to students:

- A brief presentation with an

overview of our issues in the library

- A spreadsheet of anonymous

data detailing recent behavioural issues, including the date, time,

location, number of people involved, and description of instances of poor

behaviour, gathered over a month

- Some recent comments from

student users of the library from feedback volunteered by students through

mechanisms such as meetings between academic librarians and student

representatives from the departments they support

- Some recent photographs of

library vandalism

- Copies of posters currently

displayed in the library

- Information on behaviour

displayed on our website: https://www.bradford.ac.uk/library/contact-and-about-us/regulations-and-policies/

We asked the

students to address these questions:

- How can we encourage better

use of our facilities?

- How can we better provide

group working space without it becoming a social area?

The students

were given three hours to consider the evidence and questions before presenting

their work to the class. The students’ presentations included suggested actions

as well as explanations from psychology theories that supported these actions.

This allowed students to work on a real-world problem and enabled library staff

to engage with students who may not have provided voluntary feedback otherwise.

As this was part of students’ class module, their participation was marked and

contributed to their qualification.

Implementation

We compiled

the suggestions from the students with their supporting psychological theories.

This information was gathered from our notes in conjunction with the slides

from the student presentations that were provided after the session. These were

then analysed to find those that were already in place or were not

implementable and those that could be taken forward and used to make

improvements to library services.

The library

behaviour group discussed the findings and helped plan and execute the

implementation of student suggestions. All of this is detailed in Table 1.

Table 1

Student

Suggestions and Actions Taken

|

Student Suggestions From Presentations |

Supporting Psychology Theories |

Actions Taken by the Library Staff |

|

Creating a

library identity |

·

Social identity theory ·

Social learning theory ·

Psychological frailty |

·

We created a library mural depicting desirable

library behaviour at the library entrance that was designed and executed by

library staff. Unfortunately, students

were not able to take part as initially hoped due to health and safety

reasons. ·

We continued work on inclusive library initiatives

that cut across subject, study level, and staff and student divides, such as

a library book club and promotion of existing initiatives including the book

exchange, calm space, and upcoming family space. |

|

Recruiting

student representatives to help with basic library tasks |

·

Social learning theory |

·

This had already been identified as a need by the

library and recruitment was in progress. Two Student Champions roles helped

extend available help beyond the library’s core staffed hours. |

|

Modelling

desired behaviours in specific areas |

·

Social learning theory |

·

We created the library mural at the entrance and

created study zone banners that were placed throughout the library. |

|

Creating

distinct and easily recognizable study areas for different purposes |

·

Social learning theory |

·

The library banners include distinct colours, icons,

inclusive language, and images modelling expected behaviour in each zone. |

|

Use of

inclusive and positive language in communications |

·

Social identity theory |

·

Inclusive, positive language was already in use

across all communication mediums. |

|

Increasing

surveillance and security presence |

·

Positive and negative reinforcement ·

The 4 Es |

·

The library now has two designated security guards

stationed at the information desk and roving throughout the library. Each

guard has been provided with bodycams. |

|

Use

punitive measures (e.g., loss of privileges for poor behaviour) and use of

rewards for positive use of the library |

·

Positive and negative reinforcement ·

The 4 Es |

·

The library staff undertook an update existing

policies with regards to expected behaviour and potential consequences. These

are currently being finalized by senior university staff. ·

We discussed rewarding good behaviour but decided

that there were many problems with implementing this in a fair and meaningful

way. |

|

Reintroducing

the anonymous text service used by students to report problem behaviour in

the library |

·

Social learning theory |

·

The anonymous text service had already been replaced

with the Safezone app (https://safezoneapp.com/) available

university wide instead. |

Note: For

more information on the psychological theories mentioned in the table above,

see the Appendix.

Feasible Changes to Library Service

Of the

actions we took in response the Master’s students’ suggestions (as detailed in

Table 1), the two that were most novel and impactful were the library mural and

the banners for each study zone.

Library Mural

The student

suggestions covered by implementing the library mural include:

- Creating a library identity

- Modelling desired behaviours

in specific areas

We discussed

the library identity with the student behaviour group. We came up with the idea

of a mural (see Figures 1 and 2) on the glass wall by the library entrance, as

this is an area of high footfall. We required only a small budget for art

supplies, and library staff undertook the creation of the artwork, led by Aicha

Bahij, a professional artist who is also a staff member. The

mural incorporated images of study activities in the library, modelling

expected behaviour.

Also depicted

were iconic stages of the academic year, facilities offered by the library;

books written by university staff; books on equality, diversity, and inclusion;

and a welcoming skeleton near the entry gates to add a sense of whimsy and

reflect that library users can borrow plastic skeletons.

Figure 1

Library mural

with artists (left to right) Aicha Bahij (lead), Louise Dawson, Emily Cowler, and Sean Temple.

Figure 2

Library

mural.

Banners in Each Study Zone

Student suggestions covered

by implementing the banners include:

·

Modelling

desired behaviours in specific areas

·

Creating

distinct and easily recognizable study areas for different purposes

·

Use of inclusive

and positive language in communications

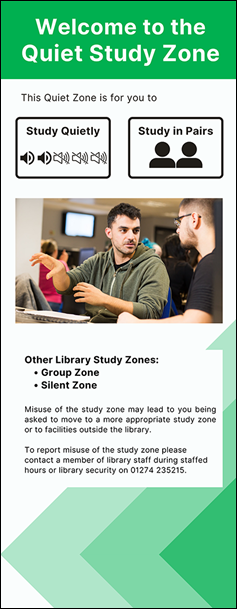

To clearly

demark the silent, quiet, and group study areas and to make them easily

recognizable, tall banners were put prominently in each study zone (see Figure

3). Each zone had a distinct colour, an image modelling the expected behaviour

in that zone, information about the number that could study together, and

acceptable noise levels in written and icon format. Additional text listed

other zones available and the consequences for not abiding by zone expectation.

All text was written in positive and plain language.

Figure 3

A quiet study

zone banner.

Unfeasible Changes to Library Services

The use of

punitive measures (e.g., loss of privileges for poor behaviour) and use of

rewards for positive use of the library were discussed by the behaviour group

and found to be unworkable within the library regulations. Whilst the students

were keen for punishment to be meaningful and act as a deterrent, the library

has limited powers. However, updated policies and a new process for dealing

with poor behaviour were already in progress. This will give a greater

consistency to the management of student behaviour not just in the library but

across the university, allowing the university to see and act upon patterns of

poor behaviour. Rewarding good behaviour was discussed, and whilst positive,

the idea was impractical as it could not be implemented in a fair and

consistent way.

Outcome

Behaviour in

the library has improved. Collaborating with students for suggestions for

improvements has brought about tangible implementable ideas that would not have

been gained otherwise. The mural in particular has led to greater student

engagement as a unique feature on campus and made the entrance of the library a

distinctive space. Visiting international students have been keen to have it as

the backdrop to their photographs with staff. The collaboration had many

positive benefits such as strengthening relationships between the library and

students as well as the library and an academic department. It brings ideas

submitted in a classroom into real world existence, enabling students and staff

to see their positive and tangible impact on a university service.

Reflection

This project

has provided a fascinating new perspective on tackling the perennial challenge

of improving student experience and tackling poor behaviour. There are several

advantages to this innovative way of gaining student feedback, which could

encourage others to try something similar. The costs are few. The requirements

were simply library staff time and a member of academic teaching staff willing

to timetable a team-based learning session for us to present our problem to.

The students produced rich feedback that was critically evaluated and, rather

than being subjective or reactionary, was backed up by established

psychological theories. It was also a unique opportunity to collaborate with an

academic department in the university.

Limitations

to the project were that we consulted only one set of students in one course,

so some student voices are missing. Additionally, master’s degree students are

often mature or may be international students so their perspectives may differ

from other students. Overall, however, this is a high impact, low cost,

repeatable, and innovative way of gathering student input on improving student

experience and managing poor behaviour.

Acknowledgements

We would like

to thank Dr. Peter Branney without whom this research

would not have been possible, Aicha Bahij for her original art and for being

lead artist on the library mural, Emily Cowler and

Sean Temple for their original art contribution to the library mural, Sarah

George for being an encouraging and guiding (tor)mentor on our first

publication, the Library Customer Services team for their collective

contribution to the library mural and Alison Lahlafi

for enabling us to undertake this research and feed into service improvements.

Author Contributions

Louise Dawson: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology,

Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review

and editing Louise Phelan: Investigation, Methodology, Project

administration, Writing – review and editing

References

Aitkenhead,

E., Clements, J., Lumley, J., Muir, R., Redgrave, H., & Skidmore, M.

(2022). Policing the pandemic. Crest Advisory. https://www.crestadvisory.com/post/report-policing-the-pandemic

Bandura, A.

(1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

Skinner, B.

F. (1974). About behaviorism. Cape.

Stufano, A.,

Lucchese, G., Stahl, B., Grattagliano, I., Dassisti, L., Lovreglio, P., Flöel, A., & Iavicoli, I.

(2022). Impact of COVID-19 emergency on the psychological well-being of

susceptible individuals. Scientific Reports, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-15357-6

Tajfel, H.

(1982). Social identity and intergroup relations. Cambridge University

Press.

Tweddell, S.

(2020). Evaluating the introduction of team-based learning in a pharmacy

consultation skills module. Pharmacy

Education, 20(1), 151–157. https://doi.org/10.46542/pe.2020.201.151157

Appendix

Psychology Theories

- Social identity theory. This

revolves around the creation of in-groups, characterised common expected

behaviour, positive and favourable beliefs about the in-group and negative

beliefs and opinions about those not part of the in-group (Tajfel, 1982).

- Social learning theory. This

posits that people learn how to behave in any given situation or

environment, based on observing and then mimicking behaviour in others

that appears to be acceptable. This can be good or bad behaviour (Bandura,

1977).

- Positive and negative

reinforcement. Under this theory, behaviour is controlled or

changed using the mechanism of offering reward and inflicting punishments

(Skinner, 1974).

- The 4 Es (engage, explain,

encourage, enforce). This is a framework for engaging with people

behaving unacceptably and escalating if required. This is often employed

by services such as the police (Aitkenhead et al., 2022).

- Psychological frailty (post

pandemic). This theory posits that people have lost or did

not gain key social skills that enable them to engage positively in

different environments. This may also include high levels of mental

ill-health in people (Stufano et al., 2022).