VOL. 2, No. 1

AbstractCommunity plays an important role in childhood education. This research has identified the community factors that affect learners’ achievement through the use of case studies. Qualitative data were captured by semi-structured interview and data interpretation was underpinned by concepts derived from human capital and social capital theories. This research identified six community factors: financial position, environment, educational status, communication and support given to schools, community child care, and unity and cooperation among community people that affect learner’s achievement (i.e., quality of education). This research also suggests that the notion of “rural community roles” tend to be thought of as “doing something for the children”. There is also an ecological balance in the relations between the community and the school. This research suggests that the human capital and social capital of the community and children reinforce each other in a reproductive loop. This means the human and social capital of family and community play a role in the creation of the human and social capitals of the children (quality education), and vice-versa. These observations on education quality add a new horizon to the knowledge base of primary education, and one that may contribute to policy-making and also facilitate further research.

Bangladesh has a strong national commitment to primary education and has one of the largest centralized primary education systems in the world (GOB, 2002). Primary education is free for all children in Bangladesh, from grades one through five. By law, children between the ages of six and ten must attend school. Drop-out rates are unacceptably high, with only 47 per cent of enrolled students completing grade five.

The literature confirms that Bangladesh has achieved remarkable progress with respect to the goals of universal primary education and gender equality in education but it lags behind in ensuring the quality of primary education (M. Ahmed, Ahmed, Khan, & Ahmed, 2007; M. Ahmed, et al., 2005; A. M. R. Chowdhury, Choudhury, Nath, Ahmed, & Alam, 2001; Latif, 2004; Majumder, 2006; MOE, 2004; MOPME, 2003, 2007). According to UNESCO (2010) “the ultimate measure of any education system is not how many children are in school, but what – and how well – they learn.” (p. 7) and “expanding access to primary schooling doesn’t necessarily imply a trade-off with improving school quality and learning outcomes” (UNESCO, 2006). It is clear that both quality and access must receive attention, and one must not be sacrificed in “a trade-off” against the other (Latif, 2004). Quantity and quality in education should complement rather than replace each other (Latif, 2004). Therefore, the quality of primary education in Bangladesh remains a big question.

Learning is a product not only of schooling but also of families, communities and peers (Engin-Demir, 2009). Learning takes place in many environments – home, school and workplace (IRBD/WB, 2006). Therefore, education is the business of schools, family and community and ensuring quality is the joint effort of all these participants (Bojuwoye, 2009; Christenson, Rounds, & Gorney, 1992; J. Epstein & Connors, 1995). The literature also shows that there is no comprehensive research done on family and community factors with regard to education quality in Bangladesh, although, these elements are recognized in the literature as key factors in enhancing quality primary education. Therefore, it is pertinent to know about the factors related to family and community in the local culture of Bangladesh in order to frame the agenda of ensuring quality primary education. In this regard, it is timely and appropriate to investigate the factors affecting the quality of primary education related to the community in the local context of Bangladesh.

The community and parents have important roles in ensuring the quality of education in schools and such involvement makes a difference (Aronson, 1996; Beveridge, 2005; M. Chowdhury, Haq, & Ahmed, 1997; IBRD/WB, 2006; Wolfendale & Bastiani, 2000). The community involvement in schools is, potentially, a rich area for innovation that has benefits far beyond access. Due to some limitations of the government in providing quality education (remoteness, bureaucracy, corruption and inefficient management), bridging the values gap between government initiatives and community desires, and adjusting to the child’s familial obligations to family interest, would help shift towards ways to mobilize a sense of community through building relationships among governments, schools and communities (Cummings & Dall, 1995). In another study, Chowdhury et al. (1997, p. 246) expresses the same view that, “ in the wake of the existing problems of failure of the ‘top down’ policy in educational management, community participation in educational planning and management has been viewed as a key to success in developing countries in general”. Parental and community involvement in school affairs has become another strategic drive of school improvement efforts in Africa (Verspoor, 2005). The literature states that there are school management committees and parents’ committees that involve parents, guardians and social elites, both in Bangladesh and African countries but the experiences reveal that such initiatives weren’t succesfull in the most cases (M. Ahmed, et al., 2005; Carron & Chau, 1996; M. Chowdhury, et al., 1997; Latif, 2004; Verspoor, 2005). However, Huq et al., (2004) found that the school management committee in high quality schools in Bangladesh showed great concern for maintaining the quality of education, and contributed to the overall educational environment of the schools, whereas, the community of low quality schools is less concerned about the same issues and has no meaningful impact on the quality of education in schools. Carron & Chau (1996, p. 278) stated that, “it is necessary to break out of this vicious circle whereby parental discouragement is met with teacher defeatism”, and, “the most urgent task is probably simply to make the school more welcoming for its users”. Similarly, “the community is likely to reciprocate by showing grater interest in the school with a partnership gradually forming” (Cummings & Dall, 1995, p.115). Rahman and Ali (2004) emphasize the role of community in ensuring the quality of education; stating that:

The last entry point to consider here is to strengthen the accountability process within the system through innovating on community – relevant and community – validated outcome indices. A shared understanding of quality can serve to reinforce the sense of community ownership and create the ground for a fuller community engagement in primary education (p. 68)

The community factors that have direct or indirect effects on ensuring the quality of primary education are: home environment, support for education, local relevance and ownership to schools, community’s lack of skills and confidence, community’s lack of cohesion and experience in contributing to school management (Verspoor, 2005); a values gap between government initiatives and community desires, children’s familial obligations to family (Cummings & Dall, 1995); urbanization, public facilities available in the community, industrial areas, use of modern technology, school location, community leaders, educational communities, conflicts of interest, donations from the community, a sense of belonging (Chantavanich, et al., 1990); the cultural gap between parent and teacher (Carron & Chau, 1996); and economic and social status of the community (UNESCO, 2004).

A conceptual framework conceptualizes, frames, and focuses the study in which a researcher’s personal observations are transformed into a systematic inquiry by reviewing the work of other scholars and practitioners on the topic, and thereby building a theoretical rationale and a framework to guide the study. Therefore, it focuses on the clear design of the study; on decisions about where to go, what to look for, and how to move to real-world observations and become more specific (Marshall & Rossman, 2006). According to this definition and scope of conceptual framework, a number of models of quality of primary education in different countries are reviewed. These are:

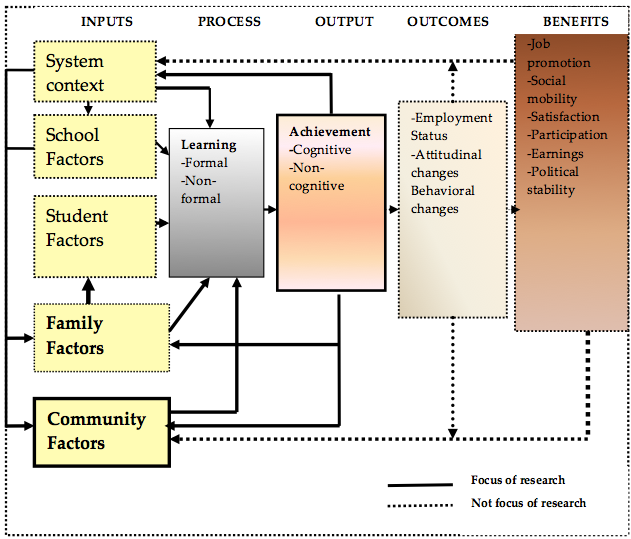

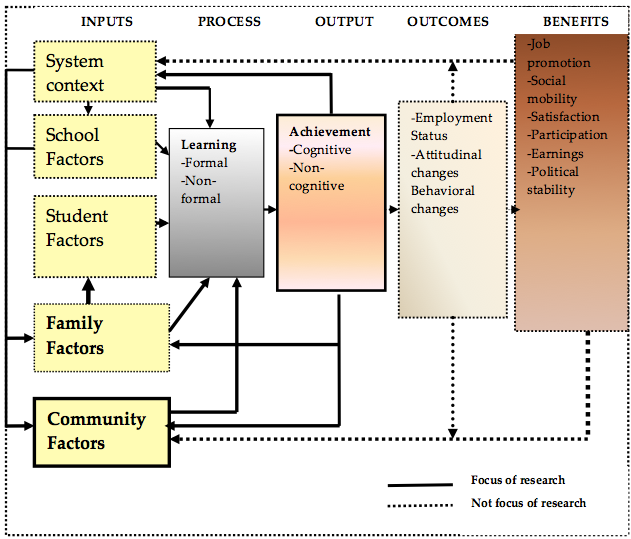

A conceptual framework of this research is therefore developed based on ‘the learning system: causes, consequences, and interaction model’ by Psacharopoulos & Woodhall (1985, 216), and the model of ‘the transformation of inputs into outputs of schooling’ developed by Verspoor (2005, 48) uniting both social capital theory and human capital theory. The model of Psacharopoulos and Woodhall shows the relationship between inputs and outputs. Like an education production function, many factors such as family, school variables and socioeconomic factors affect the educational outcomes. Here, the term ‘education function’ refers to ‘the process by which inputs are converted to outputs’ (1985, 215). This transformation model emphasizes factors such as school, system, community and family, and all the factors, to an extent, are aligned (pulling in the same direction) and the system performance is to be improved (Verspoor, 2005).

The models of Psacharopoulos & Woodhall (1985) and Verspoor (2005) are used to develop the conceptual framework of this study. Social capital theory and human capital theory are intended as a lens to guide this research. Here, the following arguments are presented as why these two models are chosen to delineate the research framework:

The conceptual framework guided the data analysis and interpretation of findings in this research. The synergy of all these issues (inputs, process, output, outcome, benefits) is portrayed in the framework as depicted below (Fig. 1). In this research, the flow system as shown by dashes, was not studied or interpreted.

According to the literature, there are two perspectives on educational process: from the education provider and from the education receiver. Family and community are the key receivers of education; and school and the government are the key education providers. Therefore, this study looks into the factors and issues of the education receiver side (community) that affects the quality of education. The community factors on achievements that are indicated in Fig. 1 by bold lines are studied. The family, community, student, school and the system context are considered as “inputs”. The schooling that took place in schools and outside the schools is considered as “process”. Children’s achievement that is the result of quality education is denoted as “outcome”. Then, “outcomes” are the sum of changes in attitude, behavior and status on the job and in society, and “benefits” are the positive changes occurring in productivity, employment, society, politics, and earnings.

Figure 1: Conceptual Framework

In this framework, it can be seen that factors of family, community, school, student and system context affect the children’s achievement through the learning process in schools and outside the schools. Students acquire human capital and virtual relations that are developed by students within the community, family and school is the social capital. Then, this social capital and human capital is transformed into outcomes and brings benefits to individual students, families, communities and the nation. The study therefore unveils what are the factors of community and how it affects learners’ achievements.

The qualitative method (case studies) is used in this research. The case study, which is ethnographic in nature, illuminated the insights related to the community factors. The aim of this research was to know rural parents’ perceptions of the community factors that affect learner achievement. Therefore, it uncovers their views and the social interactions embedded in the rural community. The epistemological position of this research stands on the constructivism-interpretivism spectrum. This research used the general inductive approach (Auerbach & Silverstein, 2003) and the mechanics of coding were developed on the basis of the data analysis process of Auerbach & Silverstein (2003).

The present research was conducted in two primary schools located in an upazila (administrative unit or sub-district) of Bangladesh. The details about the schools and the locality are presented below.

LocalityBangladesh is a densely populated country in South Asia with a population of 158.66 million (in 2007). It has an area of 147,540 km2. Its adult literacy rate is 53% (2000-2007) and 84% of its population is living on an income of less than US$2 per day (UNESCO, 2010). The population comprises the following religious divisions: Muslims (83%), Hindus (16%), Buddhists and Christians (1%). In Bangladesh, there are 496 upazilas.

The research was conducted in an upazila called Shibganj, located in the northern part of the country. This upazila occupies an area of 523.43 km2 and within this; the rural town covers an area of 26.81km2. The population of this upazila is 0.5 million, and 8.34% live in rural townships. Its literacy rate was 32.5% and the school attendance rate stood at 41.8% in 2001. In this upazila, 59.25% of the dwelling households depend on agriculture. Other sources of income are business (18.89%), non-agricultural labour (5.63%), industry (1.59%), employment (3.50%), construction (1.73%), religious service (0.12%) and others (9.29%) (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, 2005). There are fifteen (15) union parishads (UPs) in the upazila. UP is the structural unit of an upazila.

Case SchoolsPrimary education is catered through 11 types of primary schools in Bangladesh. The proposed research was carried out in government primary schools in Shibganj upazila. The government primary schools provide 75% of primary school education in the country. Parents (village informants) are interviewed. Both the perspectives of villages and schools were examined and critically analyzed. Two government primary schools located in rural areas and rural townships in Shibganj upazila have been investigated.

(1) Rural SchoolThe rural school is situated in Durlabhpur union parishad. A union parishad (UP) is the sub-unit of an upazila. It is the poorest UP in Shibganj upazila. The literacy rate of this locality is 29.66% (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, 2005) whereas the literacy rate of Bangladesh is 53% (UNESCO, 2010). Only 48.92% of its children (5-9 years old) attend primary school. According to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (2005) the total population (10 years old and above) of this UP is 33,385. Among them, 30.93% are jobless. Others are involved in various occupations, including household work (32.36%), agriculture (25.65%), industry (0.19%), construction (1.03%), business (3.64), service (1.50%) and other (6.2%).

This school is located in a poor community adjacent to a bazaar. The school has a building with separate classrooms. But the classrooms lack adequate facilities required for good study.

Figure 2: Rural School

Some of the class-rooms do not even have benches or desks (Fig. 2). There is no facility for drinking water in the school. This school has 10 teachers (6 male and 4 female) and the total number of students is 315 (in 2008).

Figure 3: Rural Town School

The school has a two-story building. It has a sufficient number of class-rooms with benches, desks and other facilities (Fig. 3). There is a tube-well on the school premises that is the source of drinking water. In 2008, the school had 374 students and 9 teachers (2 male and 7 female).

(2) Rural Town SchoolThis school is situated in Shibganj pourashava (rural town) adjacent to the upazila headquarters. It is the richest area of this upazila in terms of its population’s higher literacy rate and higher income. The literacy rate of this rural town is 41% and 45.63% of children (age 5-9 years) attend this school. The total population (10 years and above) of this paurashava is 26,707. Among them, 34.50% are in the category of jobless and looking for a job. There are various activities in which people are engaged: household work (32.68%), agriculture (12.05%), industry (1.53%), construction (2.36%), business (7.59%), service (1.67%) and other (7.62%).

As mentioned earlier, all the entire research was conducted by qualitative method (case study). The research design was delineated in such a way that the objective, design and methodology of the study allowed us to bring out and highlight the local community and grass-roots level and the functions of primary education, considering the viewpoints of parents.

Case StudyThe case study was carried out by a multiple-case studies method. This study was ethnographic in characteristic. It was conducted in two schools in poor and rich localities. The logic behind selecting schools located both in poor and rich localities was to uncover the whole spectrum of quality dimensions within a rural context

InformantsThe semi-structured interviews were conducted with the parents (n = 10) of two case schools. The key characteristics of informants who participated in the interviews are described in the following section.

In this study, data were captured by semi-structured interview and participant observation.The methods of data collection are briefly described below.

Parent Informants (PI) |

Education |

Profession |

Gender |

Age (years) |

PI 1 |

Bachelor |

Secondary school teaching |

Male |

48 |

PI 2 |

Masters |

College teaching |

Male |

43 |

PI3 |

Illiterate |

Shop keeper |

Male |

58 |

PI4 |

Bachelor |

Secondary school teaching |

Male |

35 |

PI5 |

Grade 6 |

House wife |

Female |

32 |

PI6 |

Illiterate |

Office attendant |

Male |

49 |

PI7 |

Illiterate |

Business |

Male |

35 |

PI8 |

Bachelor |

Business |

Male |

36 |

PI9 |

Secondary |

Village doctor |

Male |

38 |

PI10 |

Masters |

Officer |

Male |

44 |

Semi-structured Interviewing

In this study, semi-structured interviews were conducted because they are flexible, focused and time-effective. Merriam (1994) suggests three ways to record interview data: (1) tape recording, (2) taking notes, and (3) recording interview data by writing down as much can be remembered as soon after the interview as possible – this is the least desirable way of recording data. In this study, the interview data were recorded by both audio tape and field notes.

There are many strategies used in the interviewing process of this case study research. First, rapport was built with the informants by discussing some of their personal matters and by presenting token gifts. Then, the researcher briefed the informant on the purpose of the interview. Confirmation was given that anonymity and the confidentiality of the responses would be strictly protected. Since the researcher has grown up in this community, he knows the culture and norms of the community population and the locality as well. It was an added advantage for him to be able to capture the data in an easy way. With the assistance of the head teachers of the respective schools, the schedule was made for interviewing parents according to their availability and convenience. The interviews were conducted in Bengali., The researcher was conversant in the local language of that community, which helped a lot in understanding their thinking and views clearly and in depth, since the local language is somewhat different from pure Bangla, both in utterance and style of speaking. With their permission, the interviews were audiotaped, although some of them asked that their voices not be recorded. In these cases, the researcher adopted a strategy, whereby the informants were humbly requested to give their consent to record the interview, after explaining that if they found anything wrong with it or felt it may harm them in any way, it would be deleted directly from the tape recorder in front of them. Thankfully, however, no informant asked for this after their interview.Data analysis refers to three concurrent flows of activity: data reduction, data display, and conclusion drawing. Data reduction refers to the process of selecting, focusing, simplifying, abstracting and transforming the data; data display is an organized, abstract form of information that permits conclusion drawing and action; and conclusion drawing is the critical evaluation of the research findings (Miles & Huberman, 1994). The analysis of data is termed “coding”. According to Auerbach & Silverstein (2003) the main purpose of coding data is to move from the raw text to research concerns. The steps of data analysis are: raw text, relevant text, repeating ideas, themes, theoretical constructs, theoretical narrative and finally research concerns.

In this study, the framework of analysis (coding mechanics) was developed on the basis of the data analysis processes of Auerbeach and Silverstein (2003)

Data Preparation

The interviews were copied from the tape recorder to the computer. The interviews were conducted in Bengali. The interviews were therefore transcribed in Bengali and thereafter translated into English.

Data Analysis

Data analysis follows a process which is borrowed and adapted from grounded theory. The qualitative study of this research was conducted in two schools in rural areas as a miniature representative (case) of schools in rural Bangladesh, where the views of sample parents were analyzed. In this research, perceptions of parents on community factors were identified in their rural setting. The new concepts and knowledge base were built on the footing of prior knowledge in the field. The three steps used for data analysis are described in detail in the following:

Step One: Exploring Data and Identifying Relevant Text

The data analysis process started with the raw data: information collected from the informants by interview. The first step was to define clearly the research questions and theoretical framework, since it is important to identify the relevant text for coding. According to Auerbach &Silverstein (2003), research concern is what the researcher wants to learn about and why, and the theoretical framework is the set of beliefs about psychological processes with which the researcher approaches the study.

In this process of analysis, the relevant text was selected from the interview transcripts, keeping in mind the research concerns. These were recorded when the researcher started reading transcripts to separate the relevant text from the raw text. The theoretical framework guides the researcher in choosing what to include or exclude from analysis and it helps the researcher read the text in a more focused way without any bias (Auerbach & Silverstein 2003).Therefore, relevant texts were sorted out for coding.

After reading the transcripts, the texts are selected and copied and placed in a separate file. Each text is then marked. This helps in referring back to the original text when further review and change in the text is needed. Similarly, other texts were selected for the remaining research concerns and then put in separate files. Both individual sentences and whole paragraphs were selected and used as relevant texts.

Step 2: Initial Coding and Categorizing

This step belongs to the phase where repeating ideas are formed. The repeating idea is one expressed in relevant text by two or more research participants (Auerbach & Silverstein, 2003). They note that these ideas are the initial building units from which the researcher will move forward towards the theoretical narrative (Auerbach & Silverstein, 2003). These repeating ideas are referred to in this study as sub-themes. The researcher thought it appropriate to use sub-theme instead of repeating idea as these ideas are the building blocks of the theme. The step for creating repeating ideas (sub-themes) starts with the first selection of relevant text. The first selection is called a starter text (Auerbach & Silverstein, 2003). All interview texts were used for discovering ideas. The entire relevant texts were read and ideas that seemed related to the starter idea were copied and placed into the file containing the sub-theme. Memos were used to indicate how these selections were related. This process continued until the end of the relevant text portion. When all of the selections that were related to the first starter were completed, the second starter text was selected, highlighted and copied to the same file as in the case of the first starter. This procedure continued until the end of the selection of all relevant texts. After the ideas were all grouped, each group of ideas were read and coded according to the memos taken. Actually, each group of ideas naturally contained the name that indicated to which group they should belong. That is, the group names were self generating. Each group of ideas is collectively called a sub-theme. These sub-themes were named according to their hidden meanings. Then, all sub-themes were put in a list for further coding. This is called the master list of sub-themes (repeating ideas) (Auerbach & Silverstein, 2003).

The next step was to categorize the sub-themes into a common theme. The process of discovering themes is the same as the process of discovering sub-themes. In the same way, the starter sub-theme was selected first from the list of sub-themes. Then, sub-themes that were congruent to the starter sub-themes were highlighted as being related to the first theme and placed together in a file, accompanied by a record of the reasons for the slection. This segregation process of sub-themes into different broad categories (theme) continued until the completion of the selection of all sub-themes in the list. The same sub-themes were also put under more than one category when the researcher felt that it contained more than two meanings. In this case, these sub-themes were marked and selected further for the next selection process.

Step 3: Developing Constructs and Answering Research Questions by Narration

The ultimate aim of this step was to describe the research results by developing constructs, and weaving together the description through the process of logical and comprehensive narration. The construct is an abstract form of a group of themes. In the words of Auerbach and Silverstein (2003), a theoretical construct is “an abstract concept that organizes a group of themes by fitting them into a theoretical framework” (p. 67). The procedure for making constructs from themes is the same as that of constructing themes from sub-themes. The process of creating constructs was easier to carry out since there was a relatively small number. However, it was more difficult in a sense at this stage, since the researcher had to work through more abstract concepts.

Auerbach & Silverstein (2003) advise that in the formation of a more abstract form of data, that is, theoretical constructs, the researcher will be able to use some theoretical literature to make sense of the findings. The final stage of the data analysis process, as used in this research, was the construction of a narration that led the study towards addressing the research concerns. The necessary literature and the informant’s quotations were presented to reflect on and understand the expressed views directly. All sub-themes, themes and constructs for each research concern were presented in a table. The narration was placed under the umbrella of the theoretical framework and the research questions of the study.

Finally, each step of the data analysis is revisited for checking and coding and for the emergent process of relevant texts, sub-themes, themes, and constructs, as well as the narration process of research findings. Therefore, these were revised according to any new objectives that were found to be important.

The data analysis from parent informants produced a construct, themes and sub-themes in the framework of analysis as developed for data analysis. The coding of the parents’ data generated a construct called “characteristics of the community's frame of mind”. The construct has two themes, namely, basic characteristics and community support and cooperation. Each theme consists of several sub-themes. The in-depth discussion on these themes and sub-themes exhibited a comprehensive account of parents’ perceptions on community factors related to education quality. The construct, themes and sub-themes are presented below in Table 5).

Table 5. Construct, Themes and Sub-themes

Construct: Characteristics of the Community's Frame of Mind |

Theme A: Community Characteristics |

|

|

|

Theme B: Community Support and Cooperation |

|

|

|

Parents perceived that the environment of the community, where the school was located, is largely influenced by the roles of community leaders and the availability of resources (financial, social and human) in the community. The environment of the community, in turn, provides social networks in the community that help schools in various ways to provide an achievement trajectory for children. There are some parents’ statements on the issues of community environment that are presented below:

Each of these bullet points communicates a specific message. The first indicates the importance of community environment for children’s learning. The second expresses the relation between community environment and children’s education through the eyes of poor rural parents. The third statement acknowledges the influence of the mental makeup of people in the community in the creation of the community environment that is suitable for children’s education. The last one relates to the role of community leaders in creating a good environment in the community for children’s quality education. These leaders sought the active School Management Committee (SMC) for their children’s better learning. SMC or the community leaders can build an environment in the community through active concern and support for improving the quality of education. Parents emphasized the community’s involvement in children’s education and in creating an educational environment and awareness amongst the community’s population, explaining the value of education and in extending support to children of poor families. Of course, this depends on the community where the school is located and functions. In this respect, functionality of the community varies according to the availability of human, social, cultural and material resources.

The research confirms that the environment of a community is related to the availability of resources in the community, and the environment of the community is an important element of the community in helping to maintain quality of education in primary schools.

Community involvement in children’s education is seen in various ways (Sanders, 2001) and parental involvement is one of the important concepts of community involvement. Therefore, the financial position of families in the community also reflects the financial position of that community overall, as well as its effect on the children’s education. It is reported that poverty among guardians and the community population is the main cause of poor support in the community (Haq, et al., 2004). The parents of the schools involved in this research were poor and with a high rate of illiteratcy and, therefore, they did not know how to account for the effect of the financial position of the community on children’s learning comprehensively. However, they felt that community involvement both in local and non-local schools are necessary for maintaining education quality. They realized that the financial position of families or communities is a matter of extending support and cooperation to the school or family for children’s educational development. According to some parents:

This study suggests that financial crises of families keep many children away from attending school due to a lack of books, pencils, note-books, school dresses, and an inability to pay fees and other hidden costs. In these situations, parents suggested that the community’s population should assist economically disadvantaged families.

The literature shows that although primary education in Bangladesh is free, there are still some costs that families need to bear. This is an extra burden for poor rural families. It was found that many children came from the families who do not have proper dwellings and good environment for their studies. There is no one to guide them in their studies at home. This results in many children of poor families leaving their studies at an early age (CDRB, 2004). In an impact study of the School Feeding Programme (SFP), it was found that SFP improves academic achievement of children (A. U. Ahmed, 2004). This study stated that most of the children in the SFP come from poor families—69 % of programme households in the rural area earn less than US$ 0.50 a day per capita. These families cannot afford adequate food, and both malnutrition and short-term hunger likely affect their learning.

Therefore, this study confirms that the financial status of both family and community affect children’s learning. The financial position of family directly affects the children’s achievement. A family’s economic factors are related to these issues of the community and vice-versa.

Parent informants corroborated that, in addition to financial position and the environment of the community, educational status is another factor of the community which affects children’s learning. Their statements connected to education in the community that are related to children’s learning were considered to fall under the “education position of the community” and are are quoted below:

These statements illustrate the roles (positive and negative) of educational status in the community on children’s learning. The positive roles include educated guardians helping with their children’s learning, and providing additional support to their children’s education. The negative roles include children becoming inattentive in study in order to imitate their uneducated peers of the community. Uneducated parents do not understand the value of education and the illiterate cannot provide the necessary supports to children for their learning.

Parents perceived that educated guardians are more aware of their children’s education and that they valued their children’s education. The rural community’s people extend support and cooperation to schools and the community’s children. They also acknowledged that the absence or lack of education in the community can have an adverse effect on children’s achievements. Therefore, they saw the education of the community itself as an important factor for children’s learning.

The analysis of the data reveals that community participation in the rural schools of Bangladesh happens through participation in the School Management Committee (SMC) and Parent Teacher Association, although, support and contribution of the SMC to schools for children’s better learning is limited.. Parents expressed their views that the SMC has a potential role in schools for helping children achieveme their goals.. Parents added that the community population need to extend support and cooperation to schools in many ways. In this connection, the following parents’ statements are worthy of mention:

The above statements clearly reflect parent’s dissatisfaction with community support and cooperation as they are now practiced. They saw the community supports to schools only through the participation of the community in the SMC. They put value on the community support in rural schools in Bangladesh for achieving quality in education. How the SMC can help schools in ensuring children’s success is also explained by parents. As a result, parents can take remedial measures for their children’s development. The community, acting through the SMC, can bring any problems to the SMC for solution.

According to parents, the community communication with schools is very limited and this limited invovlement through SMC/PTA has yet to bring fruitful results for children’s achievements. It is probably due to the negligence of community leaders, misuse of power and authority by persons in the community, and the selection of inappropriate people in the SMC. However, parents admitted that community communication and support for schools has enormous potential to assist children’s success.

Parents feel that the community can extend support to the participants in the education process, such as schools, children, parents and community members to ensure quality of education. Parent informants explained how the members of the community can extend support to children for their learning. They indicated that taking care of children’s learning both in schools and communities by community leaders or parents is an important element for education quality. According to Parents informants:

Therefore, this research supports the idea that community support can contribute to elevate children’s educational achievements (Epstein, 2001) and childen, parents, schools and other community participants) are mutually benefitted in various ways (Bojuwoye, 2009).

Parents also felt that the community should extend support to schools, children and the community’s population in general in order to benefit children’s achievement levels. The community should exhibit unity and cooperation in performing these duties as necessary. According to parent informants:

There are two key messages to be distilled from these statements. First, the community has a pivotal role in creating a good educational environment. Second, the community needs to be united and cooperative. They have to sacrifice their time, resources and to share their thoughts about how the education of children can be enhanced.

The research suggests that parents feel some key community factors affect the quality of primary education. These includes the environment, financial position, educational status, communication and support available to the school, the care exhibited towards the children by the community, and the unity and cooperation evidenced amongst the community’s population. These characteristics and their association with other factors are presented in Table 6 below:

Table 6. Synthesis of Parents’ Perception

Factors |

Characteristics |

Association |

| Environment | Social capital, Human capital, Direct and indirect effect on children’s learning | Community involvement, Financial position, Education |

| Financial position | Financial capital, Direct effects on children’s learning | Support to schools, Education |

| Education | Human capital, Direct support to children’s learning | Economic status of the community, Caring of community children, Communication and support to school |

| Communication and support to school | Social capital, Indirect support towards children’s learning | Values of the community, Education and financial position |

| Caring of community children | Direct and indirect support to children’s education, Social capital | Education and financial position, Values and attitudes of the community |

| Unity and cooperation | Social capital, Direct and indirect effects on children’s learning | Communication and support to school, Values of the community |

In this study, an attempt was made to hear the voices of parents in order to uncover their views about community factors affecting the quality of education. The research maintained transparency, communicability and coherence in the process of data collection, analysis and interpretation. As both an insider and outsider, the researcher was able to take advantage of both perspectives to display a heightened critical awareness. However, this study cannot claim to be totally free from subjectivity. This study attempted to enhance the generality of the research results by providing rich and thick description and using multiple cases. The research was carried out in two rural schools of one upazila (an administrative unit) in Bangladesh (which has 496 upazilas). Therefore, the conclusions of this research are confined to these specific cases in rural Bangladesh. The applicability of specific research results is within the prerogative of the readers, who can decide as to what extent and in what context; they will be applicable.

The research concludes that some basic characteristics of the community along with its support and cooperation with schools are helpful for achieving the desired quality of primary education in rural areas of Bangladesh. The impact of this support and cooperation depends on the characteristics of the particular community. The characteristics of a community prepare the mind of the population to do something to enhance children’s education. Therefore, the research identified two kinds of community factors that affect the quality of education. They belong to the “characteristics of the community” and its “support and cooperation” themes. The research identified the following factors as key: the financial position and the community environment, the educational status of the community, communication and support given to the school, the care for community children, and any unity and cooperation exhibited amongst the community’s population.

The research suggests that the notion of “rural community roles” would be represented by the idea “doing something for community children”, and that there will be a “mutual understanding and sharing of resources and benefits”, much like a symbiotic relationship. However, the present research discovers that there is no such relationship, support, cooperation, or involvements that can play a significant role in achieving quality education. It is also observed that community members aren’t willing to communicate and cooperate with the schools for quality childrens’ education, and for their well-being. The research finds that the causes of this unwillingness may be lack of faith between the community population and teachers, a lack of awareness amongst the community’s population regarding their responsibilities to schools and also their inability to carry these out, due to their poverty and illiteracy. Another perception amongst parents is that schools are government organizations, which don’t require parental assistance to ensure the school’s success.

Despite parents’ dissatisfaction with community involvement in schools, the research suggests that community involvement in children’s education by extending support and cooperation to schools and families, would be an avenue to achieve quality education in rural primary schools in Bangladesh.

Dr. Md. Shafiqul Alam is the Joint Director (Training and Research Division) Bangladesh Open University. He has published a number of articles in the field of education in national and international journals and conference proceedings. E-mail: shafiqul_bou@yahoo.com