VOL. 1, No. 1

The twenty-first century is witnessing innovative practices in the advancement of learning in the developed world as a consequence of the technological revolution of the period and the increased demand for higher education (Bax, 2011; Barab, King and Gray, 2004; Roman, 2001). Education is perceived as the cornerstone for development, sustainability and modernisation (Fitzpatrick and Davies, 2003).

The boom in open, distance and e-learning has changed the quality of life for many people, since it offered additional venues to higher education to overcome problems of exclusivity and scarcity, especially at times of shrinking public funding (Dhanarajan, 2011). The founding of the Open University in Britain in 1969 targeted an almost unlimited audience with innovative teaching and learning modes. Since it was founded, more than 1.5 million students have taken OU courses. The Open University was rated “top university in England and Wales” for student satisfaction in 2005, 2006 and 2012.

The developing world sought to replicate the success afforded through innovative learning practices. The Arab region engaged in extensive reformation to allow for new systems of learning that would provide for accessible and diversified opportunities to learners at an acceptable cost. However, concerns were voiced along the axis of equality and social justice (Wilson, Liber, Johnson, Beauvoir, Sharples and Milligan, 2007; Dudeney, 2007). Innovative learning modes have been associated with polarizing the developed and developing countries, the promotion of western thought, and the furthering of socioeconomic substrating. Debates have emerged on the pedagogic fit of the newly promoted approaches for the region, allegations of social isolation, dropout rates, faculty strain, and urban concentration, in addition to a number of scholastic uncertainties.

A survey was conducted on a random sample of learners studying through an innovative hybrid mode of learning to explore participants’ perception of the new system. Two thousand and five hundred students took the survey from all faculties at the Arab Open University in Lebanon. The survey was conducted for the periods of Fall and Spring, 2012-2013. It ensured anonymity of participants for validity of results.

The findings are as follows:

Efforts need to focus on:

The Need for Innovations in Learning

The twenty-first century is witnessing innovative practices in the advancement of learning in the developed world as a consequence of the technological revolution of the period and the increased demand for higher education (Bax, 2011; Barab, King and Gray, 2004; Roman, 2001). Education is perceived as the cornerstone for development, sustainability and modernisation (Fitzpatrick and Davies, 2003).

The boom in open, distance and e-learning has changed the quality of life for many people, since it offered additional venues to higher education to overcome problems of exclusivity and scarcity, especially at times of shrinking public funding (Dhanarajan, 2011). The founding of the Open University in Britain in 1969 targeted an almost unlimited audience with innovative teaching and learning modes. Since it was founded, more than 1.5 million students have taken OU courses. The Open University was rated “top university in England and Wales” for student satisfaction in 2005, 2006 and 2012.

The developing world sought to replicate the success afforded through innovations in learning specifically after declarations on its cost effectiveness and technologic advancement. In the Arab world, the growing population in the region looked up to higher education in the period following its independence (1950-1960) to fulfill its aspirations of development, sustainability and equality. Higher education providers multiplied from no more than ten universities in 1950 to more than 200 in the last decade (Samoff, 2003). However, the growing public demand for access to higher education required governments to make available additional resources.

The Arab Regional conference on Higher Education that convened in Beirut in 1998 confirmed that, “Higher education in the Arab states is under considerable strain, due to higher rates of population growth and increasing social demand for higher education” (UNESCO, 1998, p. 44). The declaration called for “harnessing modern information and communication technologies … to make available programmes and courses that can cater for the needs of the region … through multiple and advanced means .. breaking through the traditional barriers of space and time” (UNESCO, 1998, p. 45).

In response to such a call, the Arab region engaged in extensive reformation to allow for new systems of higher education that would provide for accessible and diversified opportunities to learners at an acceptable cost. The idea of offering innovative education outside the traditional classroom and to potentially unlimited numbers of learners held a great appeal. Such systems had to rely heavily on modern information and communication technologies to alleviate pressure on governments and traditional higher education institutions in the region.

Innovative Learning Provisions in the Arab World

In the past two decades, efforts in the Arab region have concentrated on establishing three main modes of education that incorporate innovative learning provisions and that offer flexibility of scheduling for learners, opportunities to study without the need to travel and learning at one’s own pace:

1. Traditional universities with open learning centres

Such universities offered dual modes of education through distance learning as well as conventional ones. Examples of such higher education providers in the Arab world are the open learning centres in the universities of Cairo, Alexandria, Assiut and Ain-Shams in Egypt. Open learning centres in these universities offer distance modes of education and award degrees at undergraduate and postgraduate levels in a variety of disciplines (Egyptian Universities Network, 2013). Another example is the distance education centre of Joba University in Sudan, with a branch in Jordan. The centre offers Bachelor’s level degrees and Master degrees (Majdalawi, 2005). The third example is the open learning centres in Syria, which utilize distance education modes of teaching to award Bachelor’s degree from Damascus university, Aleppo university and Al-Baath university in Syria (Al-Baath Open Learning Centre, 2013).

2. Universities offering single distance education mode

These offered distance education through correspondence as well as print, audio and television broadcasts. This category is represented by a number of centres in the Arab world. Tunisia has the Higher Institute for Continuing Education, offering teacher training programmes at secondary and primary levels through distance education. The Open University in Libya offers programmes leading to the award of a Bachelor’s degree (Libyan Open University, 2004). The Continuing Education University in Algeria offers distance education to students who failed the general secondary diploma, with the aim of helping them to gain employment or continue with higher education (Jamlan, 1999). Al-Quds Open University awards Bachelors degrees in various specializations, equivalent to Bachelor awards from conventional universities. It also offers non-degree courses and plans to offer Master degrees (UNESCO, 2002).

3. Virtual online universities

The Syrian Virtual University established agreements with leading western online universities in Canada, Europe, Australia and the USA to provide “world-class education without barriers” and to offer “requirements for enrollment and graduation, that foster academic quality” to students in their homeland (Syrian Virtual University home page, 2003; UNESCO, 2002a). The programmes that were offered were some of the most well-funded programmes in a region where, “only about 1% has the time, money and opportunity to attend top universities” (McCormick, 2000, p. 60).

Threats Facing Innovative Learning Provision in the Arab World

The global change in the digital age resulted in innovations in learning taking a technical guise and utilizing multiple learning modes in education. However, there were concerns that, “many Third World countries have uncritically accepted positivistic claims .. despite the evidence which suggests that this is not always the case” (Guy, 1999, p. 49). Contradictory arguments were raised along the axis of equality and social justice (Wilson, Liber, Johnson, Beauvoir, Sharples and Milligan, 2007; Samoff, 2003; UNESCO, 2002a):

Polarizing developed and developing countries

In a report by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) a cautious concern was voiced over whether the information and technical revolution is leading to the globalization, or the polarization of the world along the axis of haves and have nots (UNDP, 1999, p. 61). In addition to this, and in terms of cost, the pattern of developing education material suitable for open, distance and e-learning requires financial resources that are not available in the developing world. Potashnik and Capper (1998) report that the United Kingdom, the Open University spends “as much as 1 million GBP to produce one new course” (p. 44). The cost involves design teams, content specialists, production specialists and team managers. These work together for a period of up to three years to produce a single new course (Potashnik and Capper, 1998, p. 44). In most cases institutions wishing to offer innovative learning through open, distance and e-learning in the developing countries often rely on ready-made material imported through academic agreement from western universities. This brings forth another concern, that of the appropriateness of the imported material.

As for learners, they must acquire computer hardware and software as well as Internet connections to be able to benefit from open, distance and e-learning. According to a UNDP report 50 million households in the United States and about 50 million in Europe have at least one computer (UNDP, 1999, p. 58). By contrast South Asia, which has 20% of the world population, has less than 1% of the world's Internet users (UNDP, 1999, p. 62).

Promotion of Western thought

Heavy reliance on readymade foreign programmes have negatively impacted innovative learning modes in planning and use, a case in point is the open education centres in Egypt (Majdalawi, 2005). The same flaws have been identified in the Tunisian, Libyan and Algerian experience. Muthui and Gachiengo (1999) observed that the process can be “an instrument for perpetuating and even deepening dependency relationship between developing and developed countries” (p. 26).

The arguments that were put forth to defend the importing of western knowledge and ideology in readymade material is based on the notion of the objectivity of scientific material which makes them non-controversial. However, the same argument cannot be extended to social, literary and history studies. Western approaches to philosophy, literature and social sciences may be controversial in some contexts in a developing region (Al-Khatib, 2011).

Socio-economic substrating

Communities in the developing world are divided across substrates of urban and rural, male and female, young and old, rich and poor. UNDP reports that in the resource-deprived developing world: “a new barrier has emerged, an invisible barrier that, true to its name, is like a world wide web, embracing the connected, and silently, almost imperceptibly, excluding the rest. The typical internet user worldwide is male, under 35 years old, with college education and high income, urban based and English speaking, a member of a very elite minority worldwide” (UNDP, 1999, p. 63). The same report notes the disparity between electronic haves and have nots in the developing countries with men “vastly outnumbering” women who account for 4% in the Arab states, 7% in China and 25% in Brazil (UNDP, 1999, p. 62).

Critics have proclaimed that open learning has not led to an improved quality of life for the marginalized and powerless in the developing countries. On the contrary, it served “betting on the stronger” through accentuating and reinforcing the worst problems of inequality, specifically in terms of access to resources and attainment of the required skills (Wilson, Liber, Johnson, Beauvoir, Sharples, and Milligan, 2007).

Pedagogic fit

Arab societies are still skeptical of innovative learning practices such as open, distance and e-learning. The region still struggles with the concept of non-traditional education and the majority do not believe that new learning modes offer innovative educational experience, but rather other facets of teaching through correspondence. (Aldrich, 2003; Barab and Duffy, 2004; Dudeney, 2007; Hubbard, 2009; Kimber, 2003).

In many countries of the developing world, the pedagogy of education involves rote learning and memorization. Innovative learning practices such as open, distance and e-learning involve different pedagogic approaches that are more learner-centred, investigation-based and autonomous. Guy observed, “Theories and practices in distance education have emanated from industrialized countries and the metaphors that are used signify the attitudes and values and the modes of thinking that are highly representative of those countries. Terms such as individual learning, personal work… self pacing, evaluation and autonomy… represent much of the thinking about distance education in the developed world at present and contain specific ideologies which may not be consistent, or appropriate in third world cultures” (1999, p. 58).

Social isolation

The loss of face-to-face interaction in some distance learning contexts is one of the serious drawbacks reported of new learning modes. Resnick (2000) warns against isolation which undervalues the role of education in preparing students for civic engagement and citizenship participation. Mathews (1999) observes that students like being on a university campus and interacting socially and intellectually with fellow students and teachers.

Drop rates

Potashnik and Capper (1998, p. 43) argue that completion rates are generally much lower for distance education students as evident in the drop out statistics, with an overall rate of 40 percent. This raises concerns about whether traditional face-to-face instruction is a more effective way of working with and retaining students.

Faculty strain

New learning modes require faculty to divide their efforts into teaching, administrative follow up and research, in addition to a high level of training in the use of technology. Most of the part-time tutors employed in developing countries come from the pool of traditional universities and, hence, require extensive training.

Urban concentration

Most centres offering open and distance education are located in the major cities and have no geographic spread. This reduces efforts of outreach to rural and remote areas, where they are most needed.

Scholastic uncertainties

In the developing countries open learning institutions generally seek global certification and review to attain full recognition. There are still uncertainties in relation to the admission criteria and the compatibility of the awards. Two decades into the venture and the opportunities for traditional entry qualifications remain limited, with few or none catering to professional-level courses or needs.

The Survey

Having identified the above major concerns, a survey was conducted on a random sample of learners, to explore participants’ perceptions on whether the new hybrid learning method supported their developmental needs. The survey aimed at identifying learners’ views on the efficiency of the education system, the quality of education, resources, support, delivery methods, progress within it, and the development of the skills needed to meet market requirements. The survey was administered to 2500 students studying through the open system of education. Participants were chosen at random from all faculties at the Arab Open University in Lebanon. The sample could be indicative of future trends as it provided the views of randomly selected participants at various levels of study. The survey was conducted electronically and ensured the anonymity of respondents. The data were maintained in the quality assurance records at the university, for the period of Fall 2012-2013, and Spring 2013. The limitations relate to the study being carried out in one region.

The Arab Open University is a pioneering educational enterprise in the Arab World that was initiated following studies on the developmental needs of the region. It was founded on the ideological basis of equal education opportunity, accountability, transparency, tolerance, freedom of access to information and equality before the law.

The Arab Open University makes use of modern information and communication technologies to offer innovative blended learning modes combining tutorials, audio, video, electronic mediums and printed material to overcome restrictive selections by traditional education institutions, in contexts where priorities have to be made within available budgets. The Arab Gulf Fund headed by HRH Prince Talal bin Abdel Aziz, instituted seven branches so far for the Arab Open University in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Egypt, Lebanon, Bahrain and Oman, to target marginalized sections of society and offer good quality education for learners on low income, women and working people.

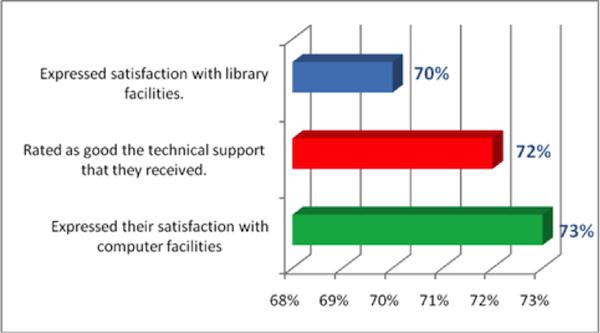

Disjunction, Rupture or Continuity

The Arab Open University incorporated innovative learning modes and targeted investment in technologic provision to provide higher education, and to increase opportunities for learners in the global market. AOU invested in computers, servers, and networks to offer an infrastructure that can serve online and networking requirements for the new initiative of blended learning. Seventy-three percent (73%) of the total surveyed (1825 out of 2500 students) expressed their satisfaction with computer facilities, access to Internet and online learning resources. Lab assistants provided support and hands-on training to help new students acquire the computer literacy skills needed to use the system. Seventy-two percent (72%) rated as good the technical support that they received and that aided their integration in the new technological environment.

Course information, material, assignments are made available on the University’s Learning Management System (LMS) to support learners in pacing their studying. The university offers physical and virtual library resources. Seventy percent (70%) of the participating students (1750 out of 2500 students) expressed satisfaction with library facilities, which helped develop in them a range of cognitive skills including critical thinking. Curriculum, however, required some grounding in the needs and problems of society to help students apply the learned skills to their immediate context.

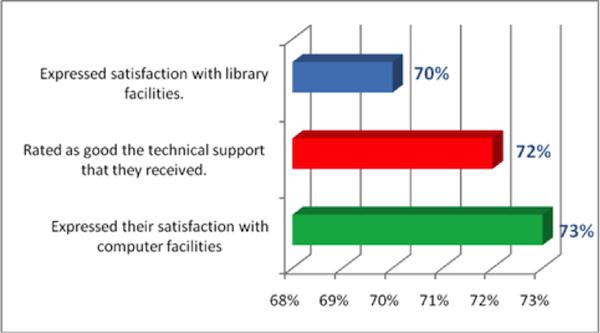

To help overcome socio-economic substrating, the Arab Open University targets female applicants as well as people on low income to integrate disparate social groups, increase economic productivity and support social cohesion in nation building. Statistics confirm a forty-five percent (45%) female student body at AOU – Lebanon in the year 2012 – 2013.

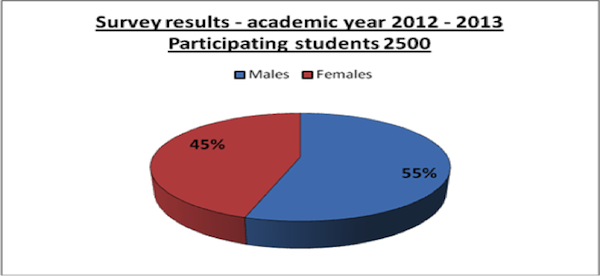

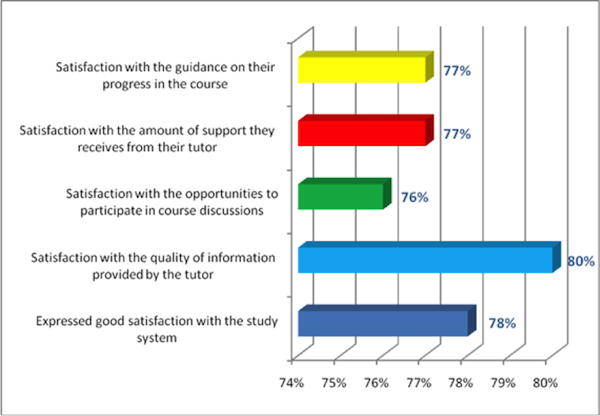

To overcome problems of social isolation as well as the skepticism associated with new learning modes, the Arab Open University adopted a blended learning model that has a minimum set of contact hours with students through tutorials and office hours. Students expressed satisfaction (78%) with the study system, the quality of information provided by the tutor (80%) and the opportunities to participate in course discussions (76%).

Recruited academic staff are given full training on the characteristics of the open system before assuming their tutor role within the system to ensure the best scholarly and professional performance. Survey results indicated that students were content with the amount of support they received from their tutor (77%) and guidance on their progress and development throughout the semester (77%).

Repurposing Innovative Learning Modes for Development and Sustainability in the Arab World

Innovative learning modes in the Arab region need to invest more effort to impact development and become equivalent to its counterpart in the developed countries. There is a need to conduct awareness campaigns in the region to educate the population on innovative learning modes, in order to overcome the serious implications of negative beliefs that are hampering their development.

The materials developed for a specific region need to be directly related to the developmental needs of learners in that region. Arab universities offering open education need to start thinking about programmes that can advance their graduates and that are compatible with their cultural context, instead of relying wholly on programmes and materials developed by Western universities.

Training workshops need to be offered to educational staff on innovative learning modes and their benefit and importance in offering access to wider sections of society. Staff commitment, as well as training and support, are key to the success of this endeavour.

There is a need to establish national standards that can assure the academic quality, cultural appropriateness and relevance of course material to the context of the Arab world. This would redress the doubts surrounding innovative learning modes and channel appropriate educational policies.

There are qualified organizations that can help establish a pan-Arab accreditation agency to secure the quality of innovative modes of education and support an Arab Network for Open and Distance learning. These include the Arab Gulf Program for United Nations Development Organization (AGFUND), the Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development (AFESD), the Islamic Educational, Scientific and cultural Organization (ISESCO), the Arab Bureau of Education for the Gulf States (ABEGS) and the Association of Arab Universities.

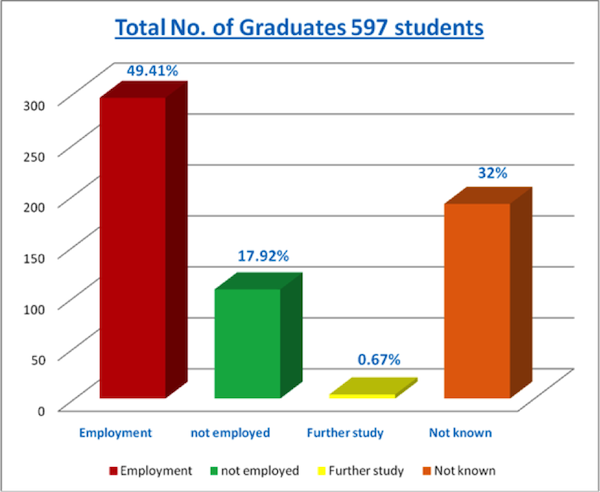

The quality of learning is measured by the learning achievement and development of learners. There are good indicators that are provided from the stakeholders, the students, and the market. Statistics provided by the student affairs record for the period of 2011 – 2012 confirm that half of the graduates found employment upon graduation. However, more efforts, resources, funds, collaboration and quality assurance means are needed to sustain this process in the Arab region.

Conclusion

The increase in demand for higher education, specifically in the developing world, has made resorting to innovative modes of education essential for development, and as a means to gaining academic qualifications specifically for people on limited incomes as well as for working and marginalized groups. The Arab region is inconsistent in terms of population size, national income, literacy levels, resources, prosperity, etc. Such factors need to be taken into account when planning a vision and mission, objectives and the values of new learning modes in the region.

Finding an alternative to traditional modes of education should be a priority for this part of the world, amidst the economic restrictions in the wake of the Arab revolutions and the instability of the region. The cultural divide between rural and urban areas affects access to education. However, open and distance education in the Arab world can solve some educational challenges of access and elitist provisions.

Education systems need to be able to help learners develop the cognitive, social and behavioural skills required in labour markets, with an eye to local and global needs. The experience of the Arab Open University favours exploring simultaneously hybrid teaching and learning modes that can satisfy local and wider contexts and serve different learning styles.

The findings are as follows:

Efforts should focus on:

Innovative modes of learning should continue to be the cornerstone for development in the region, well into the future because of pressing economic factors, globalization and the technical revolution. Global changes will have their impact; some will contribute to advancing innovative learning practices, while others need to be addressed to prevent negative implications. Sustainability will be related to the ability of providers to identify, at an early stage, the concerns of recipients, engage in two-way cultural exchange, incorporate culturally diverse themes and provide structured frameworks for innovative learning practice that can ensure quality and satisfy the concerns of the ministries of education regarding the standards of innovative learning modes in the developing world. Recipients, on the other hand, need to engage in researching and evaluating the new learning approaches to identify emerging problems and propose working solutions. Innovative learning modes will be indispensable to the development of the Arab region.

Hayat Al-Khatib has several publications in the fields of Applied Linguistics, English Language Teaching, Open Distance and E-Learning, Pragmatics, Discourse Analysis and Functional Grammar. She serves as associate editor in the Linguistic Journal ISSN: 1718-2298, the European Scientific Journal (ESJ) ISSN 1857 7431 and is the editor in chief of the Centre of Applied Linguistics Research (CALR) Journal ISSN 2073 1175. E-mail: hkhatib@aou.edu.lb