VOL. 2, No. 2

AbstractThe teaching and designing of modules at Zimbabwe Open University (ZOU) is the principal responsibility of a single body of teaching staff, although some authors and content reviewers could be sourced from elsewhere if they are not available in ZOU. This survey, through a case study, examines the involvement of lecturers and staff in the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies in instructional materials development for open and distance learning (ODL). The study inquired into the time lecturers spent on module development and writing, their levels of satisfaction with the materials they produced, their preferences with regard to teaching and instructional materials development strategies, and their views on how the process of instructional materials development at the university could be improved. The study found out that there is need for more time for materials development, better coordination and planning, greater consultation among colleagues, and adequate support services in instructional materials development for ODL to improve on the quality of modules. The department should be fully involved in instructional materials design and development to be effectively familiar with the ODL mode of learning and the students for whom the materials are intended. There is need for course writers (designers), prior to developing instructional materials, to spend time in the regional centres, which are located in the ten geo-political regions of Zimbabwe, so that they become familiar with the local learning context. One of the main recommendations is that there is need for course writers and content reviewers, as well as editors, to always undergo training in ODL and instructional materials development for ODL.

The Zimbabwe Open University (ZOU) is the only institution of higher learning mandated by the Government of Zimbabwe to offer open and distance learning (ODL). ZOU started as an offshoot of the University of Zimbabwe’s Centre for Distance Education (CDE) in 1993 to accommodate those people who would not have been in a position to go to conventional, residential, tertiary institutions for further education due to inadequate funding or other commitments. In 1996, the centre became the University College of Distance Education (UCDE). On 1st March 1999, through an Act of Parliament, UCDE became the ZOU. ZOU offers degree and non-degree programmes through ODL. The teaching / learning system comprises printed materials (popularly referred to as modules) as the main medium of instruction, face-to-face tuition supported by audio and video materials and other ODL methods whenever those are available. This paper analyses how the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies (DGES) is involved in module/instructional materials development and the sustainability of that process. The production of modules by ZOU is quite pertinent because other conventional universities tend to look down upon ZOU modules; however, these modules are widely used in all universities in Zimbabwe. In addition, some of the part-time tutors and module writers are from these conventional universities. Various departments in ZOU should, therefore, be more involved in module production so as to enhance quality and show good academic standing.

The aim and objective of this study was to assess how the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies is involved in module production.

The research objectives were to:

Collaborative Team Approach to Learning/Work

Cooperative learning and/or collaborative learning incorporate group work. People learn from one another through observation, imitation and modelling through encompassing attention, memory and motivation through continuous reciprocal interaction between cognitive, behavioural and environmental influences (Bandura, 1977). Collaboration entails colleagues being responsible for one another's learning as well as their own and reaching that goal implies that they have helped each other to understand and learn. On the other hand, Hill (2011) says that collaboration requires a conscious effort to create a way of working that promotes cooperation among different parts of an organization to achieve its shared goals and, in this case, the shared goal is the development of world-class learning materials (the modules). The collaborative team approach should be used in the development of teaching/learning materials as the module is the teacher and yields high products through the cross-pollination of ideas. Furthermore, collaboration leads to the sharing of resources as well as the fact that people are more likely to get their work done on time, and more people with diverse experiences leads to better products. However, the team approach is not necessarily effective without the right team members, good team management and a conducive environment for individual contribution.

Cooperative learning facilitates the completion of a specific end product in groups. Cooperation and collaboration appear to overlap. In collaborative learning, peers take full responsibility for working together, building knowledge together, changing and evolving together and improving together. Collaborative and cooperative learning is based on constructivism, premised on the understanding that knowledge is constructed and transformed by peers, so that each individual can become a self-directed learner. Depending on the group’s autonomy, the module writing leader may have to provide very precise instructions about the writing process. Instructions should include: how to get started, the level to which the material should be pitched, what type of participation is expected from colleagues and how the final product should look. An illustration of instruction is detailed in Appendices 1 and 2 which are instructions given to module writers, editors and content reviewers by MDU in order for team members to come up with comparable ODL learning materials, because, in ODL, the module is the tutor, the syllabus and the learning material.

Assessments of members’ contributions can be done through participation (quality and quantity), preparation (collaboration), punctuality (interpersonal skills), respect (interpersonal skills), contribution of ideas (collaboration), creativity (problem-solving) and commitment (collaboration). Active exchanging, debating and negotiating ideas within groups increases interest in doing work together. Importantly, team members become critical thinkers (Totten, Sills, Digby & Russ, 1989). Team members working in small groups tend to learn more, as they keep the information longer and also their work depends on "group goals" and "individual accountability" (Slavin, 1989). Hence every group member has to learn/do something. People who learn most are those who offer and accept elaborated explanations about what they are learning and how they are learning it (Webb, 1985). Technological advances and changes in the organisational infrastructure call for teamwork within an organisation. People need to think creatively, solve problems, and make decisions as a team, therefore; this research intended to study department involvement in the production of ODL materials at ZOU.

What is so Special about ODL?

What ODL is, continues to change due to evolving technology. The definition of ODL, as used at the ZOU, is related to this definition by the Commonwealth of Learning (COL):

Open and distance learning is a way of providing learning opportunities that is characterized by the separation of teacher and learner in time or place, or both time and place; learning that is certified in some way by an institution or agency; the use of a variety of media, including print and electronic; two-way communications that allow learners and tutors to interact; the possibility of occasional face-to-face meetings; and a specialised division of labour in the production and delivery of courses (Commonwealth of Learning, 2004).

ODL has distinct features that separate it from conventional education. These features include the separation in time and space of teacher and learners; industrialised processes; scalability and cost efficiency; and the use of technology for learning, flexibility and reach (Rumble, 1989). The key characteristics of ODL are openness, instructional design, and learner centeredness and support. The ODL philosophy that education is a human right is based on openness with regard to people, places, methods and ideas, as indicated by Rumble (1989). In ODL, the learning materials take the place of the teacher. Therefore, materials need to be consistently and carefully designed, planned, tested and revised. Unlike textbooks, ODL materials use embedded learning devices and design to encourage and support self-study (UNESCO, 2001). Instructional design has been defined as: the systematic development of instructional specifications using learning and instructional theory to ensure the quality of instruction. According to Rowntree (1994), effective ODL materials have to be:

ODL material development is rooted in the following questions, which ZOU Department of Geography and Environmental Studies and MDU should bear in mind as they embark on module writing:

Open learning is an approach to all education that enables as many people as possible to take advantage of affordable and meaningful educational opportunities throughout their lives through: sharing expertise, knowledge, and resources; reducing barriers and increasing access, and acknowledging diversity of context.

Principles

Learners are provided with opportunities and capacity for lifelong learning. Learning processes centre on the learners and contexts of learning, build on their experience and encourage active engagement leading to independent and critical thinking. Learning provision is flexible, allowing learners to increasingly determine where, when, what and how they learn, as well as the pace at which they will learn. Prior learning and experience is recognised wherever possible; arrangements for credit transfer and articulation between qualifications facilitate further learning. Providers create the conditions for a fair chance of learner success through learner support, contextually appropriate resources and sound pedagogical practices.

This paper presents a case study of module development at the Zimbabwe Open University (ZOU). The case study research design was used, since it allows data from multiple methods. Questionnaires were administered to identify: the reasons behind materials production; to explore the mode of operation, spatial dynamics and factors influencing the selection of data collection strategies, including observation, and key informant interviews. Key informant interviews were conducted to participants in Table 1 below, including the reasons why they were interviewed.

Table 1. Participants Who Took Part in the Study

Participant |

Reason(s) for Participation |

No. |

Dean - Faculty of Science and Technology |

Provides academic and strategic leadership within their Faculty. Plays a pivotal role in the overall academic and strategic development of the Faculty, and is an ex officio member of the University Administration. |

1 |

Chairperson - Dept of Geography and Environmental Studies (DGES) |

Chief administrator of the department and the primary representative of the academic discipline. Maintaining standards of the discipline, and meeting the professional expectations of the departmental faculty. |

1 |

Lecturers / Regional Programme Coordinators (RPCs) – DGES |

Normally the authors of the modules and are responsible for editing, content reviewing, marking and setting examination and assignment questions as well as teaching/tutoring. |

8 |

Director - Materials Development Unit (MDU) |

Is the general overseer of the unit who reports to the Director, Information Communication and Technology (ICT)? |

1 |

Manager - MDU |

Deputises the director and works hand-in-hand with the Director in the overall function of the unit. |

1 |

Editors – MDU |

Responsible for the day-to-day operations of the MDU |

2 |

Students - BSc (Hons) GES |

Consumers/Readers of the module, i.e., the module is the syllabus for a specific course. |

10 |

Stages in Module Production at ZOU

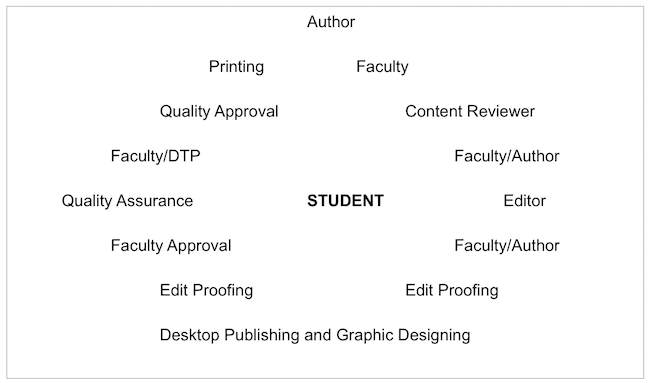

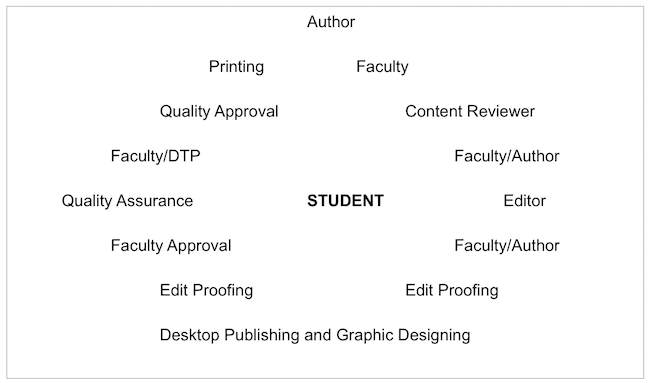

At the ZOU, module production goes through different stages involving skilled and experienced personnel all with a common goal of producing quality product. Every ZOU module has a preamble that says that teaching and learning materials are user friendly and written by professionals, who are highly qualified and experienced, from Zimbabwean universities, research institutions and industry as well as other tertiary institutions in the country and sister institutions in SADC Region and abroad. The main stages in module production (Fig. 1) are as follows:

The DGES identifies the courses that are involved in the Bachelor of Science (Honours) in Geography and Environmental Studies, the only programme running with 40 courses/modules in the institution.

A module writer with the requisite qualifications and experience is identified both within and outside ZOU by the department.

The department, through the Chairperson, recommends the name of the author and content reviewer to the Human Resources Department on recommendation by the Dean.

The Human Resources Department normally approves the name of the writer and content reviewer through the issuance of a contract specifying the terms of agreement, such as the period in which the module has to be produced, and remuneration and other terms and conditions. A writer/content reviewer/part-time editor accept and sign the contract to start work.

Once the contract is signed, module writing begins and on completion, the module is handed back to the department which will in turn forward the draft module to the content reviewer.

Figure 1: The Diagrammatic Module Processing Movement

Deans’ Remarks on the Development and Provision of Study Material

Deans desire a situation where developers of study materials continue to maintain standards, review modules and include current trends across the board (for all the modules and programmes on offer). Chairpersons and Programme Coordinators indicated that the ZOU should always contract writers with experience and qualifications in using and preparing ODL materials for the benefit of the user. Authors should be hired based on their qualification and experience in the development of ODL materials.

Perceptions on the Quality of ZOU Modules

Quality is the ability to satisfy customers’ needs and expectations on both price and non-price factors. According to Menon (2007), quality is a characteristic of the products and services an organisation offers. At the ZOU, quality in the production of learning materials (modules) is ensured through the involvement of team members with many different skills, capabilities and interests, who come together with the common purpose of producing ODL materials (Webb, 1985; Vengesayi, 2011). However, clients have their own perceptions on the quality of ZOU modules. This is evidenced by responses from ZOU module users, who expressed that ZOU learning materials were of high quality since some students and tutors from institutions of higher learning and other universities use the modules during their teaching and learning. However, all the student respondents argued that there are some modules that are outdated and need review. The same students said that ZOU modules are used by students in all universities in Zimbabwe because their colleagues who are in other universities often ask for modules from them. As is common in any situation, there are those who feel that some modules need reviewing because some of the information they contained was outdated, a view held by all Geography Lecturers who feel an urgent need to revise / rewrite some modules that were written when the university opened its doors in 1999.

The Challenges of Collaborative Team Approach to Module Writing

Involving many people for a common purpose during module production has its challenges, for example:

Therefore, the faculty should be involved at every stage of module development in order to guide team members particularly on issues that are subject specific (technical).

Challenges Faced in Module Writing

At the moment there is a lack of current material (e.g., books, manuscripts and journals) to use during the writing process, although the use of online resources has greatly improved the situation. There is a lack of critical software, such as anti-plagiarism software to check written work for the amount of plagiarism, grammar check software to correct grammatical errors, spelling mistakes and misused words and finally Geographical Information Systems (GIS) software for the creation of maps. There is also insufficient time allocated to write modules, since staff has their permanent duties either within or outside ZOU. The ZOU module writing style is not well-adhered to by authors (e.g., referencing, layout, objectives, activities, etc.) and we observed that in recently written modules, authors have been using different writing styles. This is despite the fact that MDU gives writers and content reviewers’ guidelines during training workshops on how to write and review modules (see Appendices 1 and 2).

How the DGES can be more Involved in Module Writing

Programme Leaders/Lecturers should always work hand-in-hand with MDU course designers and personnel from the Quality Assurance Department to ensure module quality and adequate coverage of concepts during module writing and content reviewing. The same should also be applied when existing modules are due for review. In addition, personnel from industry and commerce should be consulted on what to include in the learning materials in line with the expectations of industry and commerce. ZOU should provide the author with current books, manuscripts, journals and easy access to the library, so that they are able to produce modules that are up to date and therefore relevant. Modules with outdated information can only be used within ZOU and not by other universities/organisations, as this may cause embarrassment to ZOU and, therefore, lower its credibility or standing.

Zimbabwe Open University should also provide the authors with all software required during the writing process. Two- to three-week retreats that facilitate writing are necessary, because authors can concentrate solely on module writing when away from the university and not worry about their other duties. Divided attention impairs quality work. Adherence to contractual obligations with respect to the date of completion of the manuscript is problematic; writers need to work on a single module at a time. Writers struggle to deliver on time because they are working on several modules at once. In the same vein, there is need for a module to be written by at least two authors to improve on quality, i.e., writing teams that can share academic, technical and professional skills and knowledge so that the final product provides an intellectual and professional environment for the student. Module writing workshops and training are critical to ensure that authors maintain a uniform writing standard, as per ZOU house style.

Colour printing of modules should be done when necessary, especially in areas where graphics are needed. Some modules (e.g., GIS and Remote Sensing) need to be printed in colour. Some of the content (e.g., maps) require colour printing so that they are visible to the reader and depict features realistically. To ensure that ZOU modules are credible and world class; authors and content reviewers should have the necessary qualifications and experience (e.g., a background in the subject matter of the module being written, such as Agriculture, Counselling, Education, etc.). Module writing should not be seen as a money making venture, since this tends to compromise the quality of modules.

Writers, content reviewers and editors need to observe deadlines. MDU appointed editors should edit manuscripts within a reasonable timeframe; delays in this part of the module production cycle are a major problem at the moment. The Department was previously told that there was a shortage of editors. Since new editors have been trained and hired, one hopes the delays will be done away with. Some editors do not appear very knowledgeable with the content they edit, judging by the comments they make, hence, there is a need for ongoing training, so that all departmental members could eventually become editors of the modules for which they work with. After the Department has effected the editor's comments and sent the corrected copy to the MDU, there is a long wait until the Department is told that they will be receiving inputs from the Quality Assurance Unit. This stage should be expedited. But if each team member does his/her duty properly, these unnecessary delays would become a thing of the past.

At the ZOU, module writers, content reviewers and part-time editors are dissatisfied with late payments for their services during the learning material production process. Obviously, the result is a compromise in the quality of manuscripts submitted to ZOU for further processing. This is one critical area that has led to a slowing down of the process of module writing. When the module is finalised, it is released to the students through the regions/regional centres. The Department struggles to get an opportunity to see the finished product. To date the Department (including the authors) has not had an opportunity to view several new modules, due to financial constraints that require the modules to be printed on demand only, based on the number of registered students. This is an area of great frustration. MDU and Corporate Services need to agree on how copies of new modules are distributed to the Department and authors as well as to other units. All the lecturers indicated that the ZOU module could be sent to interested stakeholders, such as potential employers of graduates, for cross-checking the relevance of the information contained therein, provided that they are cooperative and have time to leave their co-business. This could be a fairly simple process because, before a Degree Programme is launched, it is a requirement by ZIMCHE that the views of all relevant stakeholders are incorporated (stakeholder consultation/needs assessment survey).

Geography is a multidisciplinary subject that has a myriad of career options in areas ranging from meteorology to disaster management. Geography seeks to equip students with a holistic understanding of the Earth and its systems, as well as to develop skills in graphing, measurement, analytics, mathematics and leadership. Issues analyzed include climate change, global warming, desertification, El Niño, and water resources, among others, including an understanding of global political issues between countries and cultures, as well as cities and their hinterlands, and between regions within countries.

The vision of the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies (DGES) is to be a world-class department producing environmentally literate graduates with holistic and sustainable development skills, knowledge and attitudes. DGES is committed to education about the environment, for the environment and in the environment. This is done through developing human resources for national and international environmental agencies as well as preparing non - graduate teachers (normally those with a Diploma in Education-Geography) so that they are able to teach Geography and Environmental Studies to all levels of the secondary school system. Graduates are also equipped with knowledge and practical skills so that post ‘Ordinary Level’ and ‘Advanced Level’ graduates are able to specialise in Geography and Environmental Studies. There is also training for environmental managers in industry. Research and dissemination of information in Geography and Environmental Studies is also done by both students and faculty members, so as to develop policy that is research(science) driven, as well as to empower those who work or want to work in community environmental projects. Zimbabwe is currently formulating a climate change policy and the department is heavily involved.

The majority of DGES graduates are working in various sectors of the economy as lecturers, environmental officers, safety officers, hydrologists, land planners, environmental journalists, parks and wildlife officers, economic planners and land surveyors, among others. The majority of the graduates are employed in government ministries (e.g., Ministry of Environment, Water and Climate, non-governmental environmental organisations, such as Environment Africa, WWF, as well as quasi governmental departments, such as the Parks and Wildlife Management Authority of Zimbabwe (PWLMA), the Environmental Management Agency (EMA) and the Forestry Commission (FC), among others.

Module production is a very long process at ZOU. It would be prudent if the MDU is made a stand-alone entity within the university to promote efficiency and cut down on the bureaucratic procedures that have to be followed. This is based on findings that some courses or programmes had to be shelved due to the non-availability of modules. A number of modules are old; they date back from when the programme began. These modules need to be reviewed soon. The major complaint from the lecturers is that they are not given adequate time to write modules and the remuneration is quite low. Lecturers are also saddened by the current Zimbabwe Council of Higher Education (ZIMCHE) standards promotions ordinance, which states that five module units are equivalent to one refereed paper in a journal. Part-time work is heavily taxed in Zimbabwe and this is one area that needs cooperation from all stakeholders so that there is a win - win situation in module development.

In view of the findings above, it is recommended that:

Vincent Itai Tanyanyiwa is a Lecturer, Department of Geography & Environmental Studies, Zimbabwe Open University. E-mail:

tanyanyiwavi@yahoo.com

Betty Mutambanengwe is an Editor, Zimbabwe Open University. E-mail: ?