Information and Communication Technologies for Education in an Algonquin First Nation in Quebec

- University of New Brunswick, Canada. Email: emily.m.lockhart@unb.ca

- Education Director, Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation, Canada

- Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation, Canada

- Researcher and Adjunct Professor, Department of Sociology, University of New Brunswick, Canada

INTRODUCTION

Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation is an innovative rural community in Quebec. Located 130 kilometers north of Ottawa, it is the closest First Nation to the Canadian capital. In both population and territory, Kitigan Zibi is the largest of the ten Algonquin communities. Broadband connectivity and information and communication technologies (ICT) are important to the community and incorporated into everyday operations.

The education sector in the community includes Kitigan Zibi Kikinamadinan (high school and elementary), Paginawatik (junior and senior kindergartens), Wazoson (daycare), Odekan Head Start Program, and a Post-Secondary Student Support program. This sector services approximately 206 students and 85 families. The education sector also provides services to members of the community who attend provincial school in the nearby town of Maniwaki. The Education sector's ultimate goal is to give hope and encouragement to each student to reach his/her full potential academically, emotionally, socially, physically, and spiritually. According to staff interviewed for this article, Kitigan Zibi and Paginawatig School encourage each student to become a life-long learner. The community as a whole is passionate about trying to ensure that students are given as many educational opportunities as possible.

Our study explores the use of technology in the education sector in Kitigan Zibi. It focuses on the situation of having technology readily available at school but less so at home. The transition from a technology-filled classroom to limited or no ICT access at home is a challenge, not only for individual students but also for their families and the community as a whole.

Although education is the main focus of the paper, broadband networks and ICT are heavily embedded into all the service sectors in Kitigan Zibi. The use of these tools by service providers is important but can only be sustained and developed if all members of the community have access to, and are able to actively and effectively use, ICTs both inside and outside the home. How Kitigan Zibi is using technology in its broader range of community services is explored in a separate study by the research team (O'Donnell, Tenasco, Whiteduck, & Lockhart, 2012).

The current study is based on a survey of connectivity and ICT use in households with school-aged children and interviews with community education service providers. It is evident from the interviews that ICT connectivity and use are important parts of the education sector in Kitigan Zibi, and that providers expect both will continue to evolve to better serve the community in the future.

FIRST NATIONS EDUCATION, ICT, AND BROADBAND CONNECTIVITY

A few background remarks are appropriate for readers unfamiliar with the situation of First Nations in Canada. In law, First Nations are sovereign political entities in treaty relationships with the Canadian state. Since the arrival of the European colonial powers more than five centuries ago, First Nations across this land have been engaged in an ongoing struggle with the state to maintain control over their lands and resources (Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples [RCAP], 1996). Alongside the ongoing treaty issues is the need for First Nations to control their community services as well as the infrastructure and resources they need to deliver those services in a holistic manner.

Across Canada, First Nations face serious funding challenges for education. In 2009, the First Nations Education Council (FNEC) reported major shortfalls in funding in Quebec, relative to the population growth and the increased cost of living in First Nation communities. FNEC noted that although provincial funding had increased, it was not sufficient to meet the needs of the growing communities. In 2008 alone, there was an annual funding shortfall of $233M in the province for First Nations education (FNEC, 2009a).

Furthermore, FNEC argued that although First Nation young people between the ages of six and 16 are entitled to an education comparable to that received by non-Native students, First Nation schools are unable to provide it as a result of this chronic underfunding (FNEC, 2009b). This severe lack of funding is attributed to an outdated funding formula designed by the federal government department, Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC). The formula has not been modified since 1988 despite changes in the field of education and ways of learning, and advancements in technologies and scientific discoveries. FNEC argued that while new technologies for educational purposes are available in most mainstream schools, most First Nations schools are struggling to acquire the funding they need to provide their students with these tools (2009b).

A recent field study of the situation across mainstream schools in Canada (Arntzen, Krug & Wen, 2008) found that information and communication technology is widely acknowledged as an emerging and increasingly important part of K-12 education. Most provincial departments of education recommend that ICT be integrated into K-12 curricula. The Kitigan Zibi elementary and high schools are certainly on board with this recommendation, and both have been incorporating technology such as SMART boards, videos, computers, and educational software programs into their lesson plans. Incorporating technology into teaching and learning can only be sustained with ongoing funding.

It is important to recognize that it is the quality, rather than the quantity, of technology use that is more critical to students' success. Lei and Zhao (2007) found that different types of technologies had a positive impact on students' grades. One group includes specific subject-related technologies, such as those produced to help students improve their reading skills, or to introduce Math curriculum for all types of learners at all levels. The second group of technologies focus on the students' creativity, design and construction skills. These types of programs enhance computer skills and give the students control over the technology in a way that is unique to their individual or group needs and desires.

Administering quality technology use implies several requirements. First, funding is needed for access to those computer programs that are not free to users via the internet, such as multimedia packages, editing programs, and subject specific programs. Second, training for educators to use the various programs is essential to ensure that students are getting the most out of the particular learning program. Finally, to ensure that students are able to maximize their learning experience via these programs, it is important that they are accessible from home.

Having technology readily available at school but not at home may contribute to differences in computer skill levels between students (Kuhlemeier & Hemker, 2007). The literature provides significant research on ICT use at school but little research on how students are using ICT at home.

Our broader research project is exploring how rural and remote First Nation communities in Canada are using broadband networks and ICT. Our community research in Fort Severn First Nation and Mishkeegogamang First Nation in Ontario has highlighted both the successes and the challenges associated with the broadband infrastructure and connectivity in these communities (Gibson, Gray-McKay, O'Donnell & the people of Mishkeegogamang, 2011; O'Donnell, Kakekaspan, Beaton, Walmark, Mason & Mak, 2011).

Connectivity in rural and remote communities across Canada - including First Nations communities - is substandard for many reasons, ranging from costly and difficult technological challenges to non-existent or ineffective government policies. It has been a struggle to develop the "First Mile" of broadband infrastructure in ways that support community-based ownership and control of services (McMahon, O'Donnell, Smith, Woodman Simmonds & Walmark, 2010). In addition, federal policies and funding programs have not supported access to, or effective use, of technologies by community members (Gurstein, 2003; O'Donnell, Milliken, Chong & Walmark, 2010). Whiteduck (T., 2010) documents a number of the challenges in providing technology and support to First Nation schools, as well as the leadership taken by key First Nations organizations in building the infrastructure.

At the national level, the First Nations leadership has recognized that broadband infrastructure is essential to support First Nations and to close the gaps between First Nations and mainstream education, health, economic development and services. In 2010, the AFN published an e-Community ICT model that highlighted the need for communities to secure broadband infrastructure and human resources (Whiteduck, J., 2010). In December 2011, the First Nation Chiefs-in-assembly passed a resolution for a First Nations e-Community Strategy (AFN, 2011). One objective was to apply the principles of Ownership, Control, Access and Possession (OCAP) (Schnarch, 2004) by First Nations over sustainable broadband systems.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND METHODOLOGY

The review of the literature suggested three main research questions for this study:

- To what extent is the Kitigan Zibi education sector using broadband and ICT?

- How, and to what extent are community households with school-age children using ICT?

- What challenges are households experiencing with connectivity?

Our study was conducted in collaboration with Kitigan Zibi First Nation and in partnership with FNEC. Together they facilitated meetings with community leadership, setting up interviews with community service providers, and conducting the household survey. The research protocols, reviewed by the research ethics board of the researchers' home institution, follow the ethical guidelines for doing research with First Nations communities outlined in the Tri-Council Policy Statement (Government of Canada Panel on Research Ethics, 2010).

To answer the research questions, the study used two different methods. The first was a survey on residential technology use distributed to households with school-aged children of which 94 were completed, 61 with high-school students and 33 with elementary school students. The second method was to conduct seven semi-structured interviews with community service providers who worked in the education sector. This mixed methods approach combined qualitative interviews with a quantitative survey and gave us a clear picture of how ICT is an integral part of the education services in Kitigan Zibi. It also provided insight in to the connectivity challenges for households with school-age children in the community.

STUDY FINDINGS

ICT and the Education Sector in Kitigan Zibi

Technology is an integral part of life in Kitigan Zibi First Nation. Service providers are quickly adopting new programs and tools to be more effective and efficient in the delivery of services to members of the community.

In the education sector in particular, technology is integrated into many aspects of teaching and learning. For example, SMART board technology has become a vital piece of lesson planning and educators are using these tools in creative ways to introduce new topics, to incorporate and preserve the Algonquin language and culture, and to target all types of learners. Another important tool is the internet, as one educator noted:

...in the world we live in today, you can't live without the internet. As a teacher, myself, I use it so much now. I don't visit the library; I don't have to do much research anywhere but on the internet. There are lesson plans out there; we have SMART boards; there are SMART board lessons out there that I can download. You know, it's where I go for my information for my lessons and I build my units with it, so I'd be lost without it.

Further demonstrating the effectiveness of the community's strategy of integrating a range of technology in education, another educator explained:

I find that's an advantage for students in our community that might not be there in other communities, just the technology itself, having an elementary and high school computer lab for our students to access and getting new computers every few years and even having the SMART board technology that a lot of schools don't have. We're really doing a lot in our community.

A number of students leave Kitigan Zibi to obtain a post-secondary education in nearby centres such as Ottawa and Montreal, which has encouraged educators in the community to make post-secondary preparation a key focus of their teaching strategies. One educator explained: "In my classroom, it's a larger reflection of the sort of the stated objective or the community-wide goal, and that is to put our young people in a position to make some very smart decisions about the role of technology in their postsecondary existence."

Classroom Use of ICT

As discussed in the literature review, the quality of technology use is more relevant than the quantity when it comes to student success and increased grade averages. Lei & Zhao (2007) found that having a computer in the classroom was only advantageous if students were using it for educative purposes, and that it could actually hinder learning if it was not being used in this way. When students overused computers, they tended to lose focus and spend time doing things that were unrelated to school (2007).

One high-quality use of technology in education involves subject-related programming. In Kitigan Zibi, educators are using these types of programs, some of which are available online. One educator explained that RAZ-Kids and DreamBox math are "…both very good programs that the kids use themselves." These subject-related programs require that teachers or schools purchase an annual license.

Another technology considered to be good quality for educative purposes is the type that allows students to actively create something. Kitigan Zibi students are highly engaged in innovative and creative uses of multimedia technologies to script, shoot, edit, and upload videos, as well as produce other types of artistic projects. Students at the high school level are introduced to new concepts, skills and approaches surrounding the use of technology for individual and group creativity.

Upon seeing the work created by the students in the technology classes, one can see that the students involved feel a sense of pride and accomplishment. Educators at Kikinamadinan strive to give their students not only the knowledge and skills they need to use technology to develop and launch their creative projects but also a better understanding of how technology may affect their lives. Speaking to this, one educator said:

Regardless of the career they choose, the path that they take, technology is going to play a part. Even [if] it's a matter of a student turning their back on a particular type of technology, they're making informed decisions and they're knowing what precisely they are turning their back on.... People have extensions of themselves that are digital or technological so we put them in a position to make some smart decisions about how to use those tools.

Families with School-aged Children and ICT at Home

With ICT so intertwined into the delivery of education services, it is important that students and their families are able to stay connected from home. A steady flow of connectivity from school to home allows both students to access information for assignments and teachers to prepare lesson plans. Home connectivity allows parents and other family members to access online information about support within the community, such as healthcare, daycare, cultural and housing services, that provide the holistic support necessary to ensure the best progress for the students through the education system.

The survey found that 73% of Kitigan Zibi households with school-age children are accessing the internet from home, and 27% are not connected to the internet. That statistic implies that less than 73% of households in Kitigan Zibi overall are connected to the internet. It is important to keep in mind that in surveys of the Canadian population as a whole, families with students at home tend to report higher rates of technology use than households without (Statistics Canada, 2002).

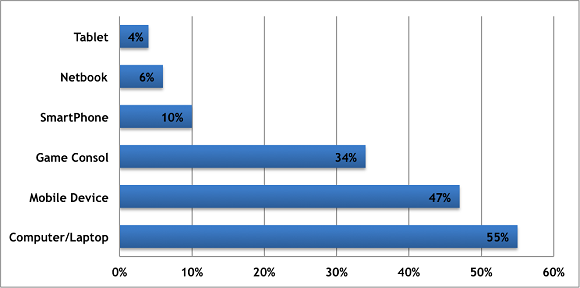

Kitigan Zibi families with school-age children are connecting to the internet in a variety of ways, by computer, through mobile phones, game consoles, tablets and other devices. Computers, mobile phones and game consoles were reported as the most common technologies used in the home. As indicated in Chart 1, more than half of the respondents (55%) reported using a computer or laptop to access the Internet. Other popular methods of connecting to the net were through mobile phones (47%) and game consoles (34%).

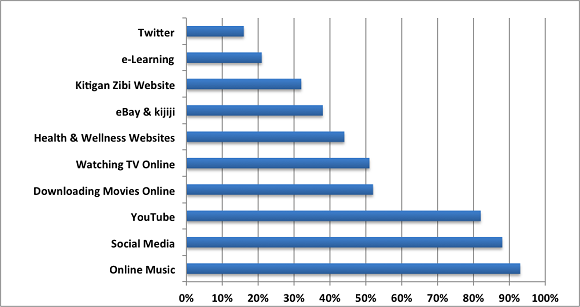

The most common uses of the internet services are illustrated in Chart 2. These include online music, social media websites, YouTube and accessing the internet. 44% of respondents indicated that they access health and wellness websites and 21% said that they used it for e-Learning. The community website (http://kzadmin.com) was also mentioned on the survey and 32% of respondents indicated that they use the site .

The finding about e-Learning is important here. Less than one-quarter of the households with school aged children are accessing e-learning from home. While there could be a number of reasons for that, including a lack of connectivity, the lack of support or training for parents or students, or cost, we must ask: how are students expected to continue improving their computer skills and to engage in e-learning if they are unable to access the programs that are available at school from home?

It is critical to acknowledge that a student's success involves an ongoing learning process, which involves engaging with their schoolwork while at home. Connectivity allows students to not only have access to the various programs they are using in the classroom but also communicate with other students and teachers via web-discussions, blogs, or email. As the Kitigan Zibi education system continues to increase its engagement with ICT, students and parents need to be able to stay up to speed with similar ICT at home.

HOUSEHOLD CONNECTIVITY CHALLENGES

Of those who responded to our survey, 17% indicated that they had 'no service' in their home. Others were waiting to get connected or trying to get connected, but were having difficulties with this process for a number of reasons. Respondents indicated that high speed internet was a fairly recent service in the community and some had not yet been able to change from dial-up to high speed. Other reasons for the lack of household connectivity were that respondents were uninterested, their computer was inadequate, or they used the internet at the home of a family member. Sharing computers between households is a common trend in other First Nation communities that we have visited.

In some cases, people are unable to connect because their homes are located outside the service area. One community member said: "The school has a lot of connections, buildings have connections, but where I am right now, I could connect only one wireless with the Bell Canada turbo chip because I don't have cable. Cable has not come to my place. It stops maybe a mile away." The Bell Turbo stick is an option available to remote homes situated outside of the zone that Bell Canada services with land lines. However, these devices are costly.

Some of the survey respondents indicated that they chose not to use the internet at home because of the high costs associated with it, and that sentiment was echoed in some of the interviews we conducted. As one community member explained, "We're too far, so we'd only get dial-up service and that's too slow. And to buy that ...like the Bell Turbo stick or whatever, it's pretty costly, so it's like, do I want to invest in that?" One community member expressed concern about cost saying: "There are community members who have children here who as parents just can't afford it. And so we can't really use it as a tool for everyone because they can't go home and use it."

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg is an innovative rural First Nation community, continuously integrating technologies into their everyday operations. Community members are, for the most part, using ICT to stay connected with others. The community's education sector in particular has placed considerable focus on the importance of ICT for teaching and learning.

Our study found that Kitigan Zibi was following the wise practice of quality of ICT use over quantity. Quality ICT use, engaging in innovative and creative use rather than just time spent in front of a computer, is linked to increases in students' grade averages. The community's educators are adamant about staying up to speed with the latest programs for enhanced learning and student creativity. They are working together to ensure that Kitigan Zibi students are receiving the education needed to achieve their post-secondary, career, and life goals. The community is preparing their students to become contributing members of the Kitgan Zibi community and society at large.

Given that ICT is woven into the fabric of the education system's everyday functions, it seems only logical that students should be using these tools from home in order to continue developing their skills. However one-quarter of the students' homes do not have internet connectivity. Homes with internet connectivity and school-aged children are using ICT mainly for social outlets and entertainment. Our survey indicates that e-Learning is not a trend for these families, although the students in the household are engaged with e-Learning from school.

Technology has considerable value for Kitigan Zibi. Our interview participants recognize the importance of bringing all community members on board as the collective moves forward. Addressing key challenges that keep community members from having access to and actively and effectively using technologies are important priorities. Kitigan Zibi will be successful in integrating ICT into everyday educational activities in the community only if all community members are able to access and use these technologies effectively.

As ICT use continues to develop in the Kitigan Zibi education system, it will be important to consider the effects this may have on students who are unable to access similar services from home. Using ICT at home could be considered as an essential element for the continued skill development and improved learning for these students.

Our study found that the primary barrier to household connectivity was lack of connectivity or affordable connection options in their local area and the cost of connectivity. These findings speak to larger challenges faced by Kitigan Zibi and most other rural and remote First Nations in Quebec and across Canada. The study indicated that some households in Kitigan Zibi are having difficulties finding the money to pay for internet connectivity. This situation reflects the experiences of many people living in other First Nations across Canada. It speaks to the need for all federal policies related the Digital Economy to ensure provisions for access to affordable broadband for everyone.

To ensure quality use of ICT, the community education sector must receive adequate funding to continue to administer, develop and deliver these programs in the schools. The current funding arrangements for First Nations education will require a more holistic approach that supports First Nations in their ICT activities and programs for education.

Broadband infrastructure provides connectivity to the community and all the services and homes in the community. Canada has no effective broadband strategy. The federal government's "Digital Economy Strategy" has yet to be revealed. The national leadership of First Nations continues to document the need for, and lobby for, a comprehensive First Nations e-Community strategy for broadband connectivity in First Nations that includes resources for ongoing support and maintenance (AFN, 2011; Whiteduck, J., 2010). The study points to the need to integrate a much more holistic concept of technology into federal First Nations education policies.

Federal policy should ensure that First Nations have the partnerships, resources and capacity necessary to provide broadband services and support ICT use in their communities. This includes support for communities to own, operate and maintain their local networks in a sustainable manner. In this way, broadband networks can support ongoing needs in the education sector as well as all other community services sectors. First Nations can also provide internet services to households, businesses and other organizations in the community. At minimum, all households in First Nations across the country should have the opportunity to be connected to broadband internet.

Options will need to be increased for Kitigan Zibi families without the money to use ICT at home. A strong focus on universal service and the right to internet access must be considered as a key point to this argument. Access to information and education is essential for the betterment of the student, their family, the education system and the community as a whole.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A special note of appreciation is extended to Kitigan Zibi First Nation for welcoming us into their community, showing us some of their achievements, and allowing us to conduct this research in collaboration with them. Thank you to Chief Gilbert Whiteduck and members of the community leadership for accepting our project and working with us to complete it. A special thanks to our community liaison, Anita Tenasco and our First Nations Innovation research partner Tim Whiteduck at the First Nations Education Council for coordinating our visits and offering continuing support throughout the entire project. We would also like to thank all the Kitigan Zibi community members and residents who participated in this study and shared their experiences with us. Those who consented to be named are: Jean-Guy Whiteduck, Keith Whiteduck, Judy Cote, Warren McGregor, Cheryl Tenasco-Whiteduck, and Anita Tenasco. The Kitigan Zibi study was conducted as part of the First Nations Innovation project (http://fn-innovation-pn.com). The First Nations Innovation partners - the First Nations Education Council, Atlantic Canada's First Nation Help Desk, Keewaytinook Okimakanak, and the University of New Brunswick - contribute in-kind resources to the project. The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council has supported our work with four research and outreach grants since 2006.