Drive-By Wi-Fi and Digital Storytelling: Development and Co-creation

- Professor and Deputy Dean, Research and Innovation, College of Media and Communication, Department of Design and Social Context, RMIT University, Australia. Email: jo.tacchi@rmit.edu.au

- Anthropologist and Senior Researcher, Experience Insights Lab, Intel Labs, Intel Corporation, United States.

- Free-lance Researcher in ICTs and Development, India.

INTRODUCTION

This paper compares and contrasts two examples of the use of information and communications technologies for development (ICT4D), or what Heeks (2010) calls 'development informatics', and the contrasting development models that underpin them. We want to examine how ICTs might enable different forms of participation in development through the notion of co-creation, and explore how underlying approaches to development influence and constrain what this kind of participation looks like in practice.

We situate the two examples, discussed subsequently, within the context of the Bottom of the Pyramid (BOP) and Human Development and Capability Approach (HDCA) as the underlying approaches informing the concerns of 'development' through the notion of 'co-creation'. Co-creation is identified as the practice through which '......"innovation" as the capacity of those in local communities to find meaningful, efficient and effective ways to respond to their very local and singular challenges and also, and equally, the challenges which they share with multiple similar communities globally' (Gurstein 2013). This we argue has significant impact on instituting notions of citizenship and creating spaces of entitlement, and thus affecting 'development'. Through the two examples, we highlight how even though the notion of 'co-creation' is central to the impact of the two discussed approaches, there are fundamental distinctions in these two approaches about its social, economic and political potentialities and implications. We argue that these distinctions ought to be considered with caution to further both the idea and the practice of 'development'.

Co-Creation in Practice: DakNet and Finding a Voice

The first example we will discuss is DakNet. DakNet brought asynchronous Internet connectivity to rural populations in Orissa, India. In the absence of 'always on' Internet provided through stable infrastructure such as optical fiber cables, this initiative was finding innovative ways to allow connection to the Internet. In this area of Orissa where the Internet was otherwise unavailable or very costly (through mobile phones, for example) the idea was to deliver a range of services such as e-shopping, online job searches, information searches and a matrimonial (match-making) service, for a nominal fee. This initiative mixed a range of technologies and platforms to deliver these services, including computers, the Internet, Wi-Fi, and local buses that served as mobile servers. The DakNet project was underpinned by an approach to development that follows the Bottom of the Pyramid (BOP) model (Prahalad 2006; Prahalad and Hart 2002). DakNet is a straightforward application of a BOP model, in that it hinged on the idea that the rural poor, who as individuals have very little spending power, together make up a sizeable market that can become profitable through designing services that are specifically developed and priced for them.

The second example comes from a research project called Finding a Voice (FaV). In this example, 15 community-based ICT initiatives across India, Indonesia, Nepal and Sri Lanka used mixes of technologies to experiment with participatory content creation. This term refers to media content that is created with participation from members of the community who normally would not have such opportunities. The concept of 'voice' was a central focus of these activities, and was defined broadly as concerning inclusion in social, political and economic areas of life; participation in decision and meaning making processes; autonomy; and expression (Tacchi 2012). This example follows an approach to development that is most closely aligned to the Human Development and Capability Approach (HDCA). This approach follows closely the work of Amartya Sen in which the objective of development concerns expanding people's real freedoms - what people are able to do and be (Sen 1999). A focus on human development in the field of ICT for development is seen by many as crucial, since otherwise development can result in 'social exclusion in the e-society' (Zheng and Walsham 2008).

These two different development models - BOP and HDCA - contrast quite starkly in many ways, yet this paper concludes that close examination of such approaches in practice can inform us about what each might learn from the other. This can be summed up in their different but in some ways overlapping ideas of 'co-creation'. Co-creation, in both of the cases, can be thought about in terms of what some now consider a 'buzzword' in development: participation (Leal 2007).

Both projects use ICTs in innovative ways as a mechanism to achieve the particular type of development outcomes desired. They can both be considered to be experiments in digital communication, and part of Information and Communication Technology for development (ICT4D). ICT4D is a lively and fast growing development field (Heeks, 2010) that is populated by a range of people including technologists, corporates, entrepreneurs, academics from a range of disciplines, and development practitioners more generally. It involves the whole gamut of traditional and emerging technologies, and has an emerging history of its own within the wider development tradition (Heeks, 2008; Unwin, 2009). This paper reinforces Tim Unwin's insistence, that when thinking about ICT4D, it is important to be clear about what we mean by the 'D', development (Unwin, 2009).

ICT4D experiments, initiatives and research do not share a single approach to development. While some are closely linked with ideas of 'progress', aligned to technological advances and targeted at economic growth for the alleviation of poverty, there are many examples of ICT4D that follow alternative paradigms of development, including 'post-development' (Rahnema, 1997). Others present alternative ways to think about poverty considering that economic growth and the role of markets as just one part of the whole picture (Sen, 1999 and 2002); while still others take into account the material, subjective as well as relational wellbeing (Gough and McGregor 2007; McGregor and Sumner 2009).

Unwin makes the point that there are many ways to connect ICT and development, following multiple paradigms (2009). Yet there is a pervasive assumption that ICT can be clearly linked with progress and development, as demonstrated by many of the digital divide debates. Even when alternative models of development are assumed to influence the policies of major development agencies, 'the discourse concerning ICT interventions invariably is reminiscent of the dominant model' (Mansell 2011). According to Unwin, while ICT might be linked to ideas of progress in a globalized world, within the realm of ICT4D there is a 'profoundly moral agenda' where the focus must be not on the technologies themselves, but on how they can be used to enable the empowerment of marginalized communities (Unwin 2009: 33)

Not all proponents of development would set out the agenda of ICT4D in moral terms. Heeks (2008:26) proposes far more self-interested motivations:

In a globalized world, the problems of the poor today can, tomorrow - through migration, terrorism, and disease epidemics - become the problems of those at the pyramid's top. Conversely, as the poor get richer, they buy more of the goods and services that industrialized countries produce, ensuring a benefit to all from poverty reduction.

Apart from compelling evidence that global terrorism rarely has strong poverty connections (Bhagwati 2006; Kruger and Maleckova 2002;), the focus here has shifted from 'the poor' to 'the non-poor'. In such a case, the poor become a means for the enrichment of the non-poor, and this shifts the concern of development. There is a contrast between a human-centred approach squarely focusing on the poor, and one that focuses on the role of profit-making enterprises, the development of new markets through the development of the poor as new consumers. While the first can be considered to be concerned with a HDCA approach (Deneulin 2009a; Sen 1999), the second echoes C.K. Prahalad's claim that there is a 'fortune' to be made at the bottom of the pyramid (2006).

For this paper we are considering what we might learn about ICT and development from a comparison of two examples of ICT4D that are underpinned by these two different approaches to development. In the first section of the paper we describe the two examples, our methodologies, and some of the relevant features of the approaches taken. In the second section we compare and contrast the two different approaches to development that lay behind the examples, polarizing in order to emphasize the differences. In the third section we attempt to collapse those differences as far as possible in order to discuss similarities that emerge in practice, and their relevance beyond these two examples to the field of ICT4D. In the final section we conclude with a discussion of the uses and meanings of 'co-creation', which ultimately appears to be the concept that most easily flows across the polarities of the two approaches and examples. Indeed it is through this concept that we can draw the two approaches together - despite their fundamental differences.

THE PROJECTS: INNOVATIVE CONNECTIONS

The two examples that we present in this paper both employ communication technologies in innovative ways to form some kinds of connections. The first example, DakNet, connected existing communication infrastructures (such as roads and buses) with new, purpose built digital Wi-Fii devices, linking potential consumers to services made available through asynchronous internet connections. The second example, Finding a Voice, experimented with the use of new digital technologies and platforms for opening up the spaces where media content is created and distributed, to allow for other voices to be communicated and heard. While both projects were about connections, there was an underlying motive of development that needs to be kept in mind. In this section we provide brief descriptions of each project initiative and highlight in each specific instances of 'co-creation' as a practice to emphasise the intersections and distinctions between the two - BOP and HDCA - and thus explore the underlying implications of these approaches.

DakNet: E-Shopping Through Drive-By Wi-Fi: The Intervention

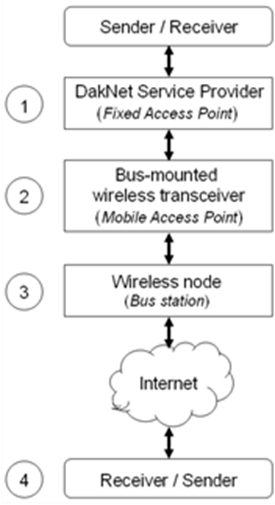

United Villages Networks Private Limited developed a low-cost Internet access model called DakNet (literally translated as postal network). It used proprietary software and hardware to support a network of rural kiosks--DakNet Service Providers (DSP)--who sold subscriptions to access a range of services (email, voice messaging, Internet) on DSP's computers. Through the computers in these fixed access points, data was uploaded through Wi-Fi transceivers mounted on local buses. The buses passed in front of these kiosks which were all located on a well used, major local bus route. Uploaded data was stored until the bus arrived at the bus station where it was transferred to the Internet via wireless protocols. Likewise, at the bus station the bus downloaded data for delivery along its route to the network of kiosks. This 'store-and-forward' system allowed DakNet to offer asynchronous networked communication to users at low cost.

Villagers along the routes sign up for a DakNet prepaid account and use the service to order items; request and receive job information; request and receive web searches on specified topics; send or receive emails, SMS or voice mail messages; or access the DakNet matrimonial (match-making) service. All of this was done offline. When the bus that had collected this data arrived at the main bus station in the city of Bhubaneswar, the stored user data was forwarded via a wireless node to the main office of United Villages, and at this point the real-time Internet was used to provide information or to source requested goods. At the time of our fieldwork in 2008 there were more than 60 kiosks which were generally run by local entrepreneurs who were already running a local business such as a photo studio, a public telephone booth, an electrical equipment shop, or a TV/radio repair shopii .

The Internet had only recently become available in the area, using mobile Internet connections, and it was still very costly. The nearest cyber cafes were located a bus ride away in urban centers. DakNet offered individual subscriptions similar to prepaid cellular mobile phone connections, with recharge services. The DakNet subscriber was provided with a unique number that served as an account login. The initial idea, was in the absence of both Internet and mobile phone networks and connections, to provide the range of services--rural email, SMS, and voicemail as well as e-shopping and information and job search facilities. However, there was limited demand for the email, SMS and voicemail services. Apart from literacy issues, there was a lack of reasons or indeed other people, to send emails to amongst individual villagers. SMS quickly became possible through the emerging mobile phone networks and affordable pre-paid mobile phone accounts, which had been unavailable when DakNet began.

The most popular service of all proved to be e-shopping. To assist e-shoppers United Villages provided a paper catalogue detailing what goods were available, and they would also source non-catalogue items. A villager could visit a kiosk and place their order themselves, or place an order through a sales person, who would ensure the order was sent to the Bhubaneswar hub via DakNet from the computer in the kiosk, with the link to the local bus via a Wi-Fi transceiver. The goods were then purchased from wholesalers in Bhubaneswar and sent to the villages, again by means of the bus network. Using this service, subscribers were able to purchase quality goods that were unavailable in local markets, and have them delivered close to their door. This service was used both by individual householders and small business. It was beneficial to local shopkeepers since they no longer had to travel to a major city to purchase specialty trade or domestic items, saving time and the cost of travel. If they had a customer who required something they would not normally stock, they were able to supply it through this service. Individuals could get better quality goods than were available locally - described to us as "luxury" items such as cosmetics, face creams and (over the counter) medications.

United Villages had a team of sales men (bhandu) linked to the kiosks, who reached out into the villages, often going door to door. Many of them started using mobile phones to place e-shopping orders for village customers during our research, removing the need to access a computer at all. The ultimate aim of DakNet was to use technology in innovative ways in order to build a profitable business that would link underserved people with very low spending power, to products and services otherwise unavailable to them through existing local markets. In this way a market would be created for Daknet services, specifically designed and delivered with this low-income market in mind.

Finding A Voice Through Creative Engagement: The Intervention

Finding a Voice (FaV) is very different from DakNet as an example of an ICT4D project. It explored participatory content creation and the role of marginalised groups not in terms of consumers of services, but rather, as consumers and producers of 'knowledge'. Conducted with support from UNESCO, UNESCO's notion of a 'knowledge society' where everyone has the capabilities of identifying, producing, disseminating and using information to build and apply knowledge was central (UNESCO 2005:191).

Different mixes of technologies and platforms were used across all of the sites. All used computers and the Internet, while some were also community radio stations or video projects. Some were community libraries, or village telecentresiii . One initiative located in a slum in Delhi, was a gender resource and ICT centre that provided a range of support services to women, teaching vocational skills such as tailoring, as well as computer and design skills. Content across the 15 sites was made for a range of purposes. In the Delhi case, training in digital media and design was to meet identified local employment needs. Some of the content was used to generate community discussion with an aim of subsequent action.

The concept of 'voice' was a central focus of the project. According to Arjun Appadurai, the 'lack of resources with which to give "voice,"' constitutes one of the poor's gravest deficits. Voice means the opportunity to express their views, and crucially, to get results 'skewed to their own welfare in the political debates that surround wealth and welfare in all societies' (2004:63). Finding a Voice was concerned with the relevance of voice in relation to poverty - influenced by people like Ruth Lister who writes that 'voice poverty' is the inability of people to influence the decisions that affect their lives, and participate in that decision making (Lister, 2004).

Working in the areas of ICT and communication for development, the concept of voice was considered to be about opportunity and agency to promote self-expression and advocacy. It concerns access, and the availability of skills to use media, technology and distribution platforms for the circulation of a range of alternative expressions. An underlying idea was that creative engagement with media and technology might provide an interesting mechanism for participatory development, as for example through the kinds of participatory content creation activities that took place in digital storytelling workshops where people had been taught to create their own short films (Tacchi, 2009).

FaV was an action research project which invited participation from community-based ICT, media and multimedia centers interested in experimenting with participatory content creation. A series of workshops was conducted through which participants explored what they understood by participatory content creation, how it might be used in their local center to help them achieve their objectives, and to develop locally appropriate strategies for implementation. In this context, and referring to ICTs for development initiatives Amariles et al. (2006) argue that, unlike 'cyberfcafes' community-based initiatives would intrinsically have 'social purpose' which makes local capacity building a key for developmental outcomes.

The local researchers observed the content creation activities in their centres, feeding this information back to the Centre staff, and to the Finding a Voice project researchers. In this way Finding a Voice showed some of the possibilities and challenges of these kinds of activities. In some cases it was found to be possible to build upon local understandings to develop culturally appropriate interfaces for local content creation.

This however was not the end of the story, and questions were raised concerning how content is created, circulated, received and used; all providing interesting reflections on issues of voice and the role of ICT in the community. Each local experiment in content creation was unique, informed to a greater or lesser extent by the local research. The ultimate aim of this project was to position marginalised people as 'voices', and to consider whether and how ICTs might provide a bridge or mechanism for those voices to be heard, and their positions recognised and responded to.

Co-Creating With Community Participation

A community radio initiative, Hevalvani Samudayik Radio in Uttarakhand, a mountain state in northern India, was part of the FaV project. This community radio initiative's intervention in the nearby villages was extensive, and involved practices of collaborative content production, which was then relayed through narrowcasting. Jugargaon was one of the villages. The village is only approachable on foot, an hour's walk from the nearest motorable road. The mountainous terrain and the limited infrastructural development in this area render the everyday of the villagers harsh, especially women who are responsible for both household chores and tending to the farms. One of the most demanding tasks for women in this region is to fetch potable water. A significant number of villages in the region still do not have piped connections; Jugargaon however had laid pipelines though with no water supply.

In their interactions with the villagers the community radio workers identified the lack of a supply of water to the piped connections as an administrative concern which needed to be brought to the attention of the responsible officials'. They produced a video recording of the villagers voicing the hardships they encountered as a result of the lack of water. This program was then played for the government official under whose jurisdiction for matters . He refused to recognize the issue and instead attempted to shift the responsibility of administrative failure to 'petty local politics in the village'. The interview with him, which was recorded, was played at a community meeting in the village. His nonchalant response to the issue compelled the villagers to undertake a more proactive stance, and thus a signature campaign was set in motion and ultimately submitted to higher authorities in the concerned department. Three days later, Jurgargaon had a regular water supply.

Seelampur is the largest resettlement colony in Delhi, India's capital city, and is a Muslim dominated locality. It is a highly conservative, a male-dominated community where women's mobility, everyday practices and 'voice' are significantly curtailed. Gender-based violence is commonplace, with the victims, women and young girls, having little recourse in seeking justice. A Gender Resource Centre (GRC) managed by the Datamation Foundation, a non-governmental organization, was part of the FaV project. Here, young women were given technical training and equipped with skills in developing a variety of media content: digital stories and newsletters, amongst others.

Violence against women constantly emerged as an intimately felt and articulated concern; and when the organization tried to raise the issue with the men in positions of power in the locality, they dismissed it as a perception of the 'outsiders' and instead insisted that gender inequality and violence was not a concern within the community. The girls and women at the GRC started to document 'real' life experiences of women who had been (or were) victims of domestic violence. These were rendered as digital stories, which were then showcased in public forums within the community. The post-screening discussions invited reactions from the male attendees which in turn compelled them to recognize the gravity of the situation and proactively work towards an awareness and advocacy plan.

Co-Creating The Availability of New Products and Goods

The United Village's e-shop initiative began with providing a paper catalog to its salesmen (bhandu), which they then circulated among the residents. The paper catalog initially included items which the organisers reckoned would be of interest to the residents, and included a range of items from sunglasses to energy efficient bulbs, medicines, toiletries and seeds. However, soon after their initial evaluation of this intervention, the organisers recognized the increasing demand for non-cataloged items by the residents and widened their scope to accommodate these demands.

Deeksha, a 24 year old homemaker, wanted to order a face cream which was not listed in the catalog and made the request to the bhandu; however not being able to read English she gave the bhandu a label cut-off from the required cream's packaging. In another instance, Kuhuri, a high school student, wanted text and reference books which were unavailable both in the local market and in the DakNet catalog. Both demands were met, and so began the shift in the system to more collaboratively building the services.

Soon a dynamic system of supply and demand was set in motion, wherein almost 50 percent of the orders placed were of the non-catalogued variety. At once DakNet was responding to the community's demands and populating their catalog, thus co-creating a heterogeneity in product demands by the consumers and supply through the e-shop.

These instances of 'co-creation' draw from the two projects FaV and DakNet which are respectively based on HDCA and BOP models of development. They are revealing about the implicit models of development emphasized by each approach. While the concerns for the HDCA is to build capacities towards empowered citizenship and extended agency to negotiate with structural issues, the BOP operates singularly within the market-driven logic of encouraging consumerism.

In a global, capital driven economy it would indeed be naïve to totally dismiss the role of increasing purchase power (and/or exercising demand), however for development practitioners and theorists it is important to situate and identify the gap between citizenship and consumerism in the local context, as well as noting broader structural considerations. An engaged and critical discussion of the two approaches can contribute towards this agenda.

DEVELOPMENT IN PRACTICE: CO-CREATION

As emphasized in the Introduction the most obvious similarity across the two examples that both initiatives were employing strategies ensuring ' …that "innovation" is done by, with, and in the community and not simply something that is done "to" or "for" the community' (Gurstein 2013). What is of particular significance however, is where the 'innovation' is located. The focus in Finding a Voice was on the 'co-creation' of content, very much in line with the ambition to build the capabilities of people to lead the kind of lives they have reason to value. With DakNet, United Villages works with local entrepreneurs, very much in line with the BOP model of trying to 'co-create' a market around the consumption needs of the poor.

London and Hart (2004) found, in their study of how MNCs and other enterprises work at the BOP, that it is crucial to learn from the 'bottom-up', that local 'deep knowledge' can help to develop successful strategies. Only when products, services and processes are co-designed, and capacities built, can the potential for enterprise development at the BOP be realised. In HDCA, there is an expectation that a development initiative and the theories of change that lie behind it are co-created, or co-constructed and defined with local actors; that it is their agency and capability sets that are promoted.

Participation or partnerships are central tenets of these approaches to development. The notion and examples of co-creation emerging from ICT4D projects thus may provide interesting mechanisms for participation across a range of development projects. This is important because participation is in fact hard to achieve, as the many critiques of participation demonstrate (Cooke and Kothari 2001; Leal 2007).

Innovative Connections

Innovation comes across in a few different ways in both interventions, for example, in the ways in which we find innovative mixes of existing and trusted technologies with new and untested ones. In DakNet the use of the buses and bus drivers for transportation of messages and goods are combined with digital technologies to create a new perspective on an old tradition. In FaV, one can find a range of local solutions that combine traditional and new technologies, as well as processes such as digital storytelling which combine local practices of storytelling with video editing software and digital cameras. For example, in Sri Lanka, a three wheeled motor vehicle commonly used to transport people and goods locally is combined with an outside broadcasting unit, mobile Internet connection and laptop to create a mobile telecentre which travels to villages to collect local stories and encourage villagers to make their own content (Tacchi and Grubb 2007).

Prahalad says that advanced, emerging technologies should be 'creatively blended' with existing infrastructures (2006: 25). DakNet ('post through the net'), as its name suggests, builds upon the traditional and trusted idea of the postman, the well-used bus service that plies between towns and villages, and the bus driver as a common carrier of goods. Added to this are newer technologies such as the Wi-Fi and the computer. Payment is made in a similar way to local chit funds or savings groups, an existing and understood method for putting aside small amounts of funds for purchases.

The rural postman has played a variety of trusted roles beyond delivering mail, sometimes reading letters to illiterate recipients, helping them to respond, and so on. Buses are the cheapest and most commonly used form of local transport, and bus drivers have often been used to send remittances or other goods to relatives, often from the city or town to the village. These technologies and infrastructures are creatively built upon by the DakNet service, which adds the Wi-Fi communication link via the buses, the computer kiosks, and the sales team who reach out into the villages. In this way villagers, literate or not, able to travel to the market or not, can access goods and services through the DakNet sales person.

Development theory and practice has long recognised the importance of social context in facilitating poor and marginalised people to realise a broad range of human rights - to development, education, health and well-being (Servaes 1999). Nonetheless, governments, donors, and development planners 'are still fixated on (the) increase in national incomes' largely ignoring the importance of context to effectively design human-centred initiatives (Prakash and De' 2007). The FaV research re-emphasised the importance of understanding context (Kiran, et al. 2009).

Participatory content creation draws upon the age-old tradition of storytelling, mixing old and new ways of communicating through developments of the digital storytelling approach (Hartley and McWilliam, 2009). Digital stories are generally short, two to five minute personal multimedia films put together using as few as two and as many as 30 photographs, sometimes with video content. They are created in community workshops. The images are used to illustrate a script, which is generally voiced by the creator of the story, typically in the first person. Two of the Centers that participated in FaV were community libraries in rural Nepal. They used the digital story community workshop approach to generate participatory wall newspapers, as well as short videos. They mixed traditional oral storytelling with digital storytelling, and used new approaches to gain participation both in the creation of traditional wall newspapers, and newer micro-documentary videos.

Within the development,process, there are different levels of and interests in participation (White 1996), and different stakeholders can be shown to employ participation for their own advantage (Michener 1998). In both of our examples, co-designed products and services, tailored to local markets, are seen to have enhanced likelihood of being taken up and valued. In both of the studies presented, there are some elements of capacity building and some understanding of 'the poor' as producers, not merely consumers. However, they are quite different in the two examples.

Prahalad recognizes the need to 'co-create unique solutions', and recommends collaboration between large firms who have investment capacity, with NGOs and communities who have knowledge and commitment. Essentially, though, this approach is concerned with transforming 'the poor' into 'consumers' for goods sold by large firms, rather than into producers of goods, from whom large firms might buy. Cross and Street (2009) consider the 'benign' language of partnership employed in the BOP approach of MNCs to be something that can obscure power dynamics that are inevitable when large-scale firms and MNCs recruit local actors to help develop new markets. Cross & Street suggest that, despite the problems involved in surmounting 'a moral opposition between "market" and "society"' BOP initiatives that make explicit their commercial self-interest, and bring poor consumers into their 'marketing, production and distribution process appear to gain acceptance as successful composites of both social and commercial interests' (2009:9).

Crewe and Harrison (1998) talk about the move in development from 'doing things for' to 'doing things with' but consider that the portrayal of partnerships as a relationship and process of cooperation that is equal, is 'inherently problematic' (Crewe and Harrison, 1998 p.71). Indeed they consider the notion of partnership as a highly ambiguous one. While for donors these partnerships may bring legitimacy and a claim to authenticity in practice they reinforce the dependency of NGOs on the donors that fund them while potentially having the effect of undermining their relationships with the constituencies they consider to be in need of their development services. Indeed, Crewe and Harrison go further to suggest that 'the exchange is inherently unequal and, at times, coercive' (ibid:74).

The BOP approach is founded on the principle that firms can make a profit from the vast numbers of rural poor, and because of this latent market, waiting for firms to profit from, it is in their self-interest to improve the lives of the poor and provide them with the means to participate more actively as consumers. However, Kuriyan et al. (2008:102) found, in practice, commercial self-interest is more likely to result in entrepreneurs catering to better off and established markets comprised of middle class, urban dwellers.

APPROACHES TO DEVELOPMENT: EMPHASIZING THE DIFFERENCES

We want to now step back and look at the approaches to development that underpin these two examples We can start by trying to understand the different ideas about poverty and development that are being employed, and draw up a set of polarized notions to emphasize the differences.

The BOP model proposes a direct relationship between business and market expansion, and economic development for the poor. The lives of the poor can be improved through market-based solutions, with firms treating the poor as a viable market. This at the same time creates a profit opportunity for business, if they target their products and services to suit the needs of this new market segment -- the four billion people at the bottom of the pyramid (Prahalad and Hart 2002). In this section we draw mostly on Prahalad's book, The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty through Profits (2006).

HDCA is concerned with expanding what people are able to do or what they can be -- what Sen calls their real freedoms (Deneulin 2009a; Sen 1999). Rather than focus on the economy or markets, the focus is squarely on the person. The end goals of development are not increased income or GDP, but the capabilities and agency of people - what they can choose to do or be. This is not to say that the HDCA approach is absolutely distinct from one that focuses on market development, such as the BOP. As Alkire and Deneulin (2009:23) make clear, there are overlaps. HDCA sees economic growth, economic stability, and increased income as important means to development, but not the ends of development. The BOP approach considers that if businesses work for their own profit by approaching the poor as a viable market, this in turn will improve the quality of life of those people.

Profit Maximization vs. Social Inclusion

In his book, C.K. Prahalad explicitly links poverty with disenfranchisement (2006). He sees the kinds of inclusions that are desirable and that will effectively lead to development as a form of 'inclusive capitalism.' Creating the capacity to consume, by working together (firms, NGOs, governments and communities) to create viable markets and appropriate products and services, can lift those at the BOP out of poverty and bring them not only access to goods and services specifically created with them in mind, but also bring them 'dignity and choice' (Prahalad 2006).

The HDCA approach would say that poverty is certainly about income and markets, but they are a means to an end rather than the end in itself. Instead, the HDCA approach sees poverty as including a lack of rights, capabilities and substantive freedoms. The aim of development is to improve capabilities and the freedom to live the kind of life one has reason to value. Sen argues that social success and development can be measured by the freedoms members of a society enjoy, including political freedoms, economic facilities, social opportunities, transparency guarantees and protective security (1999). The aim of social inclusion is strongly linked to these ideas. So, on the one hand the BOP model promotes inclusion for all in the modes of capitalism which the BOP model equates with ownership of goods traded in markets, while HDCA promotes inclusion in the kinds of social life that one has reason to value.

Active, Informed and Involved Consumers vs. Active, Informed, and Involved Citizens

A developed BOP would be made up of 'active, informed, and involved consumers' (emphasis added) (Prahalad 2006, p. xvi), whereas a developed community that has freedoms and agency would be made up of active, informed and involved citizens. The emphasis in the BOP model is to recognize those at the BOP as potential consumers, to develop goods that are targeted to their circumstances and of value to them, and attract the attention of large-scale private firms who otherwise ignore 80 per cent of humanity.

The HDCA stresses the need to create mechanisms for exercising agency in the public sphere. The emphasis in Prahalad's model is on the right to consume, while the emphasis in HDCA is on human rights more broadly. From Prahalad's perspective, the BOP deserves to be given the opportunity to consume. Large firms must appropriately adjust their products and strategies. The poor should have access to products and services that adhere to globally recognized quality standards rather than the sub-standard goods to which they currently have access. From the HDCA perspective human rights are inalienable and commonly understood as spanning the civil, political, economic, social and cultural. For the BOP approach the poor and disenfranchised must become part of the core focus of firms, who should listen to them as an emerging and potentially vast market. From the HDCA perspective they need to be the focus of governments, civic and social institutions (O'Donnell, Lloyd and Dreher 2009).

London and Hart (2004) emphasize the importance of leveraging the strengths of existing markets at the BOP (mostly informal), and co-inventing custom solutions with local and non-traditional partners. Sen (1999 p.142) argues that problems with market mechanisms are not intrinsic to 'the market' but are concerned with things like the inability to engage with markets because of a lack of information, lack of regulation of markets, the difficulty for illiterate or innumerate workers meeting global trade standards, and so on.

Deneulin (2009b:53) compares and contrasts human approaches to development with market liberalism. Both, she points out, herald the idea of 'freedom'. Major differences, though, underpin these approaches so that the idea of freedom and market liberalism is about minimizing restrictions for, and interference in, markets. HDCA promotes freedom as the freedom to do or be what one has reason to value. While human development promotes the objective of the expansion of human freedoms, market liberalism promotes the maximization of economic welfare as its objective. Freedom of choice for HDCA is understood as human capabilities and functionings (Sen 1999); market liberalism sees it as 'utility and satisfaction of preferences' (Deneulin 2009b:53) which can in part be understood as consumer choice, along the lines of Prahalad's argument that the poor have the right to be consumers of quality products. HDCA is concerned with equality and justice, while market liberalism is concerned with economic efficiency. For HDCA economic growth is a means to the ends of development, which are people. For economic growth and market liberalism approaches people are the means to grow markets, which is their focus (Karnani 2006).

CONCLUSIONS

This paper has compared and contrasted two examples of the use of ICT4D and the contrasting development models that underpin them. The notion of co-creation is present in both, but the underlying approaches to development influence and constrain what this kind of participation looks like in practice. These different approaches to development imply different development goals and lead to different possibilities in terms of development outcomes.

Since Prahalad's 2006 book on the BOP was published, the centrality of the idea of co-creation has been strengthened. Indeed 'BOP 2.0', the 'next generation BOP strategy' has been proposed (Simanis and Hart 2008; Simanis, Hart and Duke 2008) with co-creation at its core, because 'the closer the innovation efforts are to the end user, the more likely they are to respond to user needs and incorporate desired functionality' (London and Hart 2004). In fact, the centering and reframing of the concept of co-creation in BOP 2.0 is a clear indication of a move towards some of the underlying principles of HDCA, such as a somewhat shifted focus from markets to people. They pick up on the terminology, if not the underlying principles behind, Sen's notion of 'capabilities'.

In BOP 2.0, those at the bottom of the pyramid do not constitute a market as such, but a demographic classification. BOP 2.0 requires a broader approach to development than previously employed in BOP 1.0 (Simanis, Hart and Duke 2008:58). They locate the new BOP protocol within what they call the New Commons School, exemplified by Muhammad Yunus and the Grameen Bank model, which they see as a co-created approach. They consider BOP 2.0 as a move from considering the BOP as consumer, to BOP as business partner, moving from 'deep listening' to 'deep dialogue', moving from 'selling to the poor' to 'business co-venturing', where the firm is a co-creator in the development of a business opportunity (Simanis, Hart and Duke 2008:2).

The concept of co-creation is central to both examples given in this paper, but the idea of co-creation, just like ideas of partnership, and ideas of participation in development needs to be carefully examined to understand the concepts and notions that underpin it. In this article we have attempted to set out the very different approaches that underpin two examples of ICT4D in practice, and the implications of these underlying approaches on the ground. Both examples demonstrate technical and social innovations, but summon very different ideas of what constitutes 'development'.

ENDNOTES

i Wi-Fi is an abbreviation of wireless

fidelity, and is the technology that enables transmission

of data across wireless networks.

ii It is worth noting that the DakNet services

were adapting quickly, even in 2008 to the spread of

mobile networks in the area. DakNet no longer operates as

described in this paper.

iii 'Telecentre' is a widespread term for

public spaces where people can access computers, the

Internet and other digital technologies.