Sensitizing Concepts for the Next Community-oriented Technologies: Shifting Focus from Social Networking to Convivial Artifacts

University of Milano-Bicocca, Milan, Italy. Email (F. Cabitza): cabitza@disco.unimib.it

INTRODUCTION

The theme of the mutual interplay between communities and technologies is not new. For many years this theme has been of interest to research groups that gather in more or less focused venues, such as the C&T conference series. These however could hardly be put under the still too frail rubric of "community informatics" (Gurstein, 1999, 2007). Moreover, this theme also appears in broader research ambits, as is often the case when a concept, if not a term, becomes popular or it appeals heterogeneous research agendas. However, we believe that the way in which the community-technology interplay has been addressed in all these strands does not overtly establish its specificity, either in terms of theoretical foundations, intended stakeholders or involved technologies. In other words, the research questions that underlie this complex theme and the understanding of what the main issues are have not to date achieved a level of maturity and consensus around which a "thick" and tight research community could have established itself and thrive.

One reason for this can be that the notion of community itself is very broad, in spite (but also in virtue) of very technical and specific speculations from the humanities and social sciences (notably sociology, anthropology, philosophy and psychology) (Wellman, 1982). Indeed, Hillery (1955) fifty years ago had already collected 94 definitions of this concept, pointing out that his list was not be taken as comprehensive and definite at all. The term "community" has thus come to be used to denote disparate situations and very different social aggregates and structures: as rightly noted by Preece (2001), communities can be easily characterized by their physical features, such as size, location and their boundaries: in this way, communities of place are pinpointed. Alternatively discriminants can be found in the nature of people's relationships, where so called "strong ties" characterize closely-knit groups, while "weak-tie" relationships are recognized when people do not depend on each other for life supporting resources, irrespective of their value for personal and community welfare (Granovetter, 1973).

On a more conventional basis, some light form of connectivity, a common concern or interest, the sharing of some common resource, the existence of a central repository of information, or even just the use of a common application (e.g., IMs, MUDs, Fora, and now social networking sites like Facebook and Twitter) are considered enough to identify a community (Preece, 2001): in this light, one can consider the simplest "ideal types" (Weber, 1978) communities, like the so called "communities of concern", "of intent" and "of interest" according to the case, which can be either physical, virtual or hybrid (i.e., offline-online). On a more technical level instead, the detection of stronger ties or actual acquaintance among the members of the community, of constant social interactions, of a common ground (Koschmann & LeBaron, 2003) or a specific language (community jargon) can characterize so called "discourse community" (Borg, 2003) or "knowledge communities" (Cabitza et al., 2014); whereas assessing a sense of belonging, reciprocal trust, or even participation in and co-production of the same practices can be considered necessary features to either recognize or circumscribe more complex community forms, as in the case of the well-known concept of "community of practice" (Wenger, 1998).

The large number of theories and the heterogeneity of key terms that scholars have relied upon (even in the focused venues mentioned above) to call a group of people a community (see e.g., (Andriessen, 2005) for a review of the most relevant ones) is one of the signs that makes us consider the foundations of the "community informatics" structure frail.

In response to this, we are not claiming the need for a precise classification, since this would necessarily impose a predefined set of categories with which the existing open-ended and blurred community types mentioned above would be somehow forced to be associated. Rather, we advocate the definition of a set of so-called "sensitizing concepts" (Blumer, 1986), that is terms and expressions that "give the user a general sense of reference and guidance in approaching empirical instances [... and] merely suggest directions along which to look" (Blumer, 1954).

These concepts are necessary for a research community to grasp the complexity behind the surface of the phenomena observed, in order to characterize, compare, and discuss the results and findings that have been collected in different settings. This is a precondition to identify a common research field in which the various contributions are not scattered in a disorderly fashion and can each build on top of other contributions.

A symmetric argument can be done for the technology. For the most popular technologies supporting a community, their development is left in the hand of few big players while the research community is just observing and reporting on their usage in different contexts. Even when alternative proposals are developed, typically tapping in on the existing content management platforms, the demand for a critical mass of users to be involved in performing meaningful validations is stifling the development of real alternatives and the quest for disruptive innovation: the validation of this latter is then feasible only in controlled contexts where the real life of a community is difficult to reproduce.

The same holds for the learning curve that requires users to spend time to appropriate new, and sometimes increasingly complex, functionalities. Last but not least, the understanding of the true interplay between the technology and the supported community requires longitudinal and cross-sectional studies that are difficult "in the wild" and practically unfeasible in more controlled situations.However, irrespective of the difficulties mentioned above, innovation has to be pursued both in the development of new, and empirically grounded, functionalities, and in the novel usage of existing ones.

The aim of this paper is to contribute to the identification and discussion of some sensitizing concepts that we deem relevant for the study of the community - technology interplay and for the design of the latter: for this design-oriented attitude, we purposely present these concepts in terms of "affordances" (Cabitza and Simone, 2012). We use this term in the spirit of Gibson's usage (1977) to point to the offering or provision of either resources or opportunities to someone who recognizes them and is able to exploit them to become capable of performing some action, or get some value or benefit. Consequently affordances can be exhibited both by a technology that supports a community for its proficient users, and by the community itself for its integrated members, in a strongly symmetrical and correlated manner, as we will see later. Speaking of affordances and recognizing the intertwined nature of the social and technical structures (Mumford, 2006) that offer them is the approach we propose, and that we find justified by the need to connect the analysis of the current state of the research on Communities & Technologies with the conception of design principles and concrete functionalities that could take other steps forward in this research field.

TOWARDS A SET OF SENSITIZING CONCEPTS

As recalled above, the intersection of the (inter)disciplinary trajectories mentioned in Section 1 has generated a number of different definitions, each of which connotes specific characteristics that have emerged in particular studies. This proliferation happened with little concern for the confusion it could generate: different situations have been denoted by the same name, and different names have been used for essentially the same phenomena. Other denotations consider partial characteristics of communities and as such do not seem able to connote them in a way useful to understand their nature and functional needs. Sometimes the adopted technology is part of the characterization, while some other times this is left outside. This can be the case either because the technology was totally absent, or because it was considered as a marginal factor in shaping the community itself. For example the very articulated, and sometimes misinterpreted in its widespread usage (Cabitza, 2014a), concept of Community of Practice (CoP) (Wenger, 1998) does not take into consideration how technology can influence the existence, the building and maturation of a community.

The effort to move towards a more stable foundation of research on Communities & Technologies requires us to get rid of the occasional definitions that can be found in the literature in order to present them in a more structured way, according to some criteria. This approach has been taken for example in (Andriessen, 2005) but the result, although appreciable, is not fully satisfactory as it was biased by the choice of a set of big organizations as the source of its empirical evidence on the one hand, and on the other hand it did not consider the role of the technology as one primary driver of the phenomena under study. We propose an alternative way to approach this problem by grounding on a study performed at the end of the 90s by Mynatt et al. (1998).

Although the reference technology looks now to some extent outdated, this study still offers a convincing conceptual framework that captures some of the main tenets of the notion of a community: this latter is perceived as an emerging phenomenon/structure within the society, and not as a bureaucratic or opportunistic or even ideological means to obtain organizational performances or the welfare of some categories of people. This study uses the term network community. This term acknowledges that technological change produces new patterns of social life (Jacobs, 2001) and was first proposed by Castells (1997) in his analysis of the global and local effects of information technologies. Thus, in virtue of widespread infrastructures (i.e., the Internet) and the "electronics grass-roots culture" (p. 354) network groups and individuals are enabled to interact globally and interactively, but also privately (Jacobs, 2001). Also Carroll and Rosson (1996) used the expression "network community" to capture the idea of a community augmented by a networking technology offering different kinds of support of the interaction among its members. This general definition was then specialized by Mynatt et al. (1998) through the identification of some "affordances" that characterize a network community: the term affordance is here particularly appropriate as it links the idea of a community as a space of opportunities for its members with a set of services that a supportive technology can offer to seize those opportunities and gain the related benefits. The concept of network community from its very expression shed light on its two components that shape and transform each other, technology and community. In what follows we will outline the main affordances of these two macro-classes of structures.

Technology Affordances

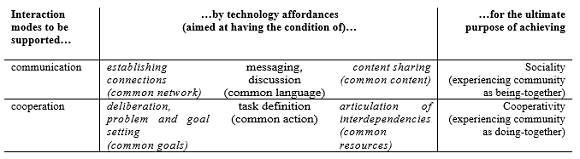

To outline the discourse on the affordances of community-oriented technology, we have to distinguish between two main dimensions of human interaction that information technologies can support through specific functionalities to maintain a network community alive and healthy: communication and cooperation (see Table 1). This is a primary distinction that was discussed also by Bannon (1989), to point out that these two dimensions are not mutually exclusive of course, but intrinsically different: indeed, any cooperative effort entails lots of communicative acts; also, but not necessarily only, to articulate activities and coordinate efforts. On the other hand, any form of communication, as a bidirectional process, entails some minimal cooperation and mutual alignment (or at least the intention for it) between who sends and who receives a message. This entanglement notwithstanding, the related human interactions can require different, although combinable, functionalities. More precisely, a necessary condition for a tool to support communication is to allow its users to share content and resources with others, namely "to put things in common", like pictures, pages, textual messages, any multimedia content: however, mutual comprehension is not granted by (nor required for) simply sharing information and electronic objects. On the other hand, understanding is necessary in messaging, as a higher level of communication, because meanings also are intended to be shared and exchanged, not just data. When also a context and a situation is "shared" along with linguistic messages, we can speak of sharing an experience, that is the necessary condition for socialization, in which the highest, in the sense of the richest, form of communication occurs.

Some form of communication is also necessary in cooperation, although this can be nothing more than the unilateral interpretation of stigmergic signs (Christensen, 2013) that promote awareness in the actors involved in interdependent tasks about what is going on, and as a spur for related decision and action. As is widely known in CSCW, actors can cooperate even without sharing common goals but rather in virtue of some positive dependency of their tasks (Schmidt and Bannon, 1992), or of their outputs. A more articulated kind of support is requested in collaborative tasks, where actors not necessarily involved in the same tasks cooperate by sharing goals, and to some extent also concerns and interests. Being involved in the same tasks produces an opportunity for a collaborative socialization; that is a co-located interaction while engaged in a collaborative effort. This dimension crosses otherwise dissimilar domains, like organizational "ordinary work" (with all its invisible and tacit elements (Star and Strauss, 1999)) and the various entertainment- and leisure-oriented pursuits, provided that a somehow structured articulation of actions is needed for their accomplishment.

To give a purposely border-line example: attending the same event organized within a community to get acquainted to each other is a way to socialize that can entail a minimum of cooperation, like filling in a form within a calendar tool for deciding the best time to meet as with e.g., Doodle.com. More often than not, a mainly communication-oriented functional support will suffice to spread the invitation to all the interested people, as it is afforded in social networking sites (e.g., Facebook and Meetup). On the other hand, collaborating to organize such an event requires a completely different support from the mediating technology: basically, something whose complexity could range from any electronic document to keep track of the confirmations received, to-do jobs, list of victuals and cuptlery, up to more articulated resources, like online polls to decide the place, the party's theme and spreadsheet to keep track of the money spent or the contributions in kind by everyone. This latter support is oriented to enabling some form of structured collaboration on top of communication, but it also has to allow for informal interactions, unexpected resolutions, collective deliberation and voting, and open and unstructured participation by the people involved.

Community Affordances

The phrase "community affordances" was first used by Mynatt et al. (1998) to denote what a community offers to the people recognizing that quality. In what follows we consider the affordances the authors identified in that seminal work, and re-elaborate them in light of the empirical research results reported in the specialist literature since then. Second, we extend that first set of affordances to capture additional features of the interplay between Community & Technology.

- Persistence - A community has to offer its members a durable, although evolving, structure of participants. The lack of an almost stable group of people to refer to and to count on can undermine both the motivations behind, and the survival of, the community itself: the latter is based on a growing mutual acquaintance and on an increasing set of conventions that shape the mutual interactions of the community members. The same holds for the technological infrastructure: it has to afford stable, although evolving, modes and means of interaction. The current and popular social networking sites (Ellison and others, 2007) do not offer this affordance, although they allow their members to circumscribe their potential interlocutors in terms of groups, "circles" and clear-cut boundaries between their friends and "all the others": indeed, "adding friends", "removing friends" and "liking their posts" are not only possible but actually promoted actions afforded by these tools underestimating the possible negative side-effects on the community members (as reported e.g., in (Marturano and Bellucci, 2009; Kross et al., 2013; Sabatini and Sarracino, 2014)). In other words, these social networking sites aim to facilitate socialization among their members but are primarily based on a quantitative and merely communication-oriented notion of it. From the technological point of view, their persistence is on the one hand guaranteed by the provider once a critical mass of members has been reached; on the other hand, just for this reason, the technological persistence is fully outside the community space of control (we will later come to this point).

- Engagement - Engagement refers to the nature of the interactions a network community can afford to its members. The overall engagement within a community is the product of the mutual engagement of its members through the channels provided by the networking technology. We can refer to the articulated connotation offered by the notion of Community of Practice (CoP) (Wenger, 1998) to briefly describe what the engagement stands for. The engagement encompasses several kinds of commitments: to simply share an interest (Champin et al., 2012); to agree with the main purposes behind the building of the community (Nathan, 1995); to perform collaborative actions accordingly; to create the conditions for this to happen as what is called a common enterprise; to contribute to the maintenance of the shared repertoire that is the protocols and conventions that the practices of the community have formally and informally established; to contribute to a social knowledge creation and to participate in social learning processes (Vesiluoma, 2007). The engagement within a community can vary in degrees of intensity: at a specific point in time, some members can feel strongly committed; others can show a peripheral participation (typical of newcomers as in the case of the CoP); others can exhibit different degrees of listening (Crawford, 2009). Individual and mutual engagement is deeply situated in a specific context and then can vary in ways that cannot be anticipated. The technological infrastructure has to be able to support the above mentioned commitments and be plastic despite their variations. Usually community members have associated different roles to account for this fact or are simply free to exploit the offered affordances. This is only a partial solution as in the first case the smooth transition from one behavior to another is fragmented by the very notion of role; in the second case, not all behaviors are recognized and equally supported.

- Boundaries - A network community affords recognizable boundaries, i.e., it is always possible to determine what belongs to its "ecology", what is outside it and what is allowed to cross the border: the latter can obviously vary depending on the situation. This affordance characterizes the networked community in that it allows one to identify several kinds of communities: communities living within organizations; civic communities, often called civic networks (Gurstein, 1999) whose members interact with the overall population and the different levels of institutions that define various spheres of citizenship; communities of place whose bounds strongly depend on the fact that its members share where they reside, work or otherwise spend a continuous portion of their time (Taylor et al., 2008), and so on. By the way, this affordance refers to only one specific dimension of a community and denoting this latter according to this dimension only is probably inadequate, if not misleading, to fully understand the nature of the group of people at hand. On the other hand, this dimension is useful to make the degree of "institutionalization" (Andriessen, 2005) of the community itself explicit, that is its degree of formality of the relationships with its "outside" context. As visionarily emphasized in (Mynatt et al., 1998), the space in which a network community lives is made up of both a physical and a virtual component: these two components are at the same time distinct and highly interconnected, as one cannot exist without the other. The technological evolution of the last decades has only made this phenomenon more evident. How this aspect is still poorly understood is testified to by the persistent emphasis on so called "virtual communities" as if their members could live and interact in the virtual dimension only. How this kind of myth is artificial is testified to by the fact that the communicative capability offered by the electronic social networks (the paradigmatic virtual spaces) are also used as a means to negotiate interactions in the physical world. In any case, the current technological infrastructures are not totally adequate to support the interplay between on-line and off-line activities when they mainly afford communication-oriented and information sharing functionalities: the affordances aimed at supporting various forms of collaboration among the community members seem to play a relevant role in bridging the physical and the virtual components of the interaction space (Preece, 2002) in a more comprehensive way. This is an area where further research has to uncover and better understand the mechanisms by which community members blend these two components in their daily practices.

- Limitations - The life of a network community is influenced by different kinds of constraints or limitations, among which those temporal patterns that Mynatt et al. (1998) dubbed 'periodicity' to account for just one relevant category related to temporality (Jackson et al., 2011). The situations and conditions influencing the community behavior can occur and recur within the community or in its broader context (that is even outside its boundaries), in both their physical and virtual spaces of interaction. The limits can be either self-imposed, i.e., established by the community members in terms of rules, policies or more tacit conventions that govern their mutual behavior, or they can be determined by the community context: the resulting "rhythms and patterns" take a different value for the community as in the first case they can be a means to strength its bonds through formal and informal negotiations and agreements, in the second case they could contribute to undermine its survival. Altogether, constraints bound actions and interactions, and can hence increase predictability, "providing a base for the mutual production of expectations about social life within the community" (Mynatt et al., 1998); on the other hand, since constraints are situated and change consequently over time, they require the community to be dynamic, resilient and reactive to unpredictable events. The technological infrastructure has to afford suitable means to support this combination of contrasting conditions. In other words, this infrastructure has to provide the community members with the awareness of the current constraints, their "strength" and related "slack", and to support their activities in accordance and compliance with those; moreover, it has to equally sustain the reflective behavior of the community members that leads to the adaptation, appropriation and continuous redefinition of those constrains with respect to the changes of the contextual conditions. This brings to the last affordance proposed in (Mynatt et al., 1998).

- Authoring - We quote the words by which Mynatt et al.

(1998) described authoring:

Network communities allow their participants to use and manipulate their space, whether as designers or users, in the sorts of flexible interactions described above. [. . . ] the very ecology: social, virtual and physical, is in a very real sense available to participants to author and reauthor continuously in the process of living in and developing the community.

This is probably the most visionary affordance those authors discuss: it anticipated an argument that years later was taken up by a number of researchers under the rubric of End-User Development (Lieberman et al., 2006) and that is still a controversial research topic as it questions (Carroll, 2004; Fischer et al., 2009; Cabitza, 2014) - and to some extent aims to overturn (Cabitza and Simone, 2014) -the role of users and designers in the practices related to ICT development. The technological infrastructure has to afford and facilitate authoring by the community members: we will come back to this issue in the next sections.

Mynatt et al. (1998) propose three additional dimensions that in our opinion can be incorporated in the above mentioned affordances. First, network communities are linked to a space where the notion of locality refers both to the physical and virtual space: this can be a way to decline the affordance of boundary; second, network communities keep alive through their ability to pursue reliable social rhythms: this is part of the periodicity affordance as described above; finally, network communities are entities that evolve through the continuous reformulation of the bindings between technology and sociality: this in our opinion is intrinsic to the affordance of authoring as this is the way a network community can adapt to the changing social and technological context. Instead, the five basic affordances do not explicitly take into account (at least) two features of a network community: trust as a basic kind of relation that supports the creation of social capital (Putnam, 2001) and what we denote as conviviality, that is a more nuanced way to conceive of cooperative engagement. These two affordances were not explicitly considered by Mynatt et al. (1998) probably because their experience was linked to communication and the technologies popular at that time to support it, more than to collaboration and knowledge sharing that are nowadays a common concern. Trust is discussed here below while conviviality will be discussed in a more detailed way in the following section for its importance in our proposal.

- " Trust - Trust is, much like community, a term where several distinct literatures exist and several ways to categorize them (Levi, 2001) as a number of scholars have so far recognized its importance "in the construction of social order, cooperation, institutions, and organizations, and even every-day interactions"; also Putnam et al. (1994) considered trust as a critical element in his original accounts of social capital. A traditional but yet sufficiently precise way to define it conceived trust as a "bet about the future contingent actions of others" (Sztompka, 2001). As such, trust cannot be afforded directly, but can be promoted in a person by exhibiting a trustworthy behavior, or by what Coleman and Coleman (1994) call "intermediaries in trust" and Mutti (2007) "reputational diffuser", i.e., individuals or either private or public institutions that, in virtue of their trustworthiness, certify the reliability and trustworthiness of other individuals/institutions. Online platforms adopt simple mechanisms to diffuse trustworthiness, reliability and reputation, like average scores derived from individual assessments of previous transactions, or the number of contents produced, and of people who "liked" it. However, criticisms have been raised whether these mechanisms can represent trust-worthiness properly, even assuming the platform displaying these indicators as a proxy intermediary, or trustworthy in itself (Dwyer et al., 2007; Fogel and Nehmad, 2009).

The above mentioned affordances can be used to characterize a given network community by describing the degree to which these (and possibly others that could emerge in the future or that we have simply forgotten) affordances are offered to the community members. In so doing, any term that can be used for the sake of conciseness to denote a specific community corresponds to a configuration (of affordances) that can be compared with other existing configurations and discussed in relation to them. This is one of the good practices that could contribute to the establishment of a (scientifically sound) research area in which each study has still to learn from the others and conceptual frameworks have still to be formulated to both account for the contribution that different disciplines have brought to the study of Communities & Technologies, and for the impact of the technological infrastructures on the nature of the network communities themselves. Indeed, the affordances offered by a network community are not only useful to characterize it through a static snapshot; rather, they are even more useful to understand how the community and its technological infrastructure co-evolve and influence each other in the unfolding of the phases constituting its life cycle (Gongla and Rizzuto, 2001).

AFFORDING CONVIVIALITY

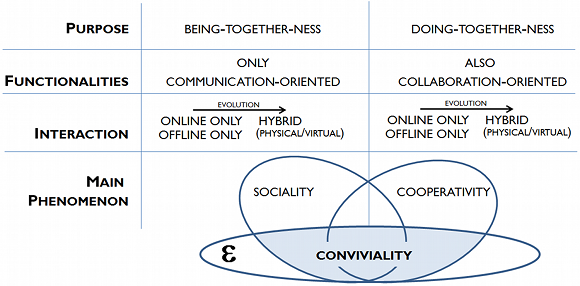

The two dimensions of human interaction we considered in the Section "Technology affordances", namely communication and collaboration, can occur both online and offline in network communities, specifically in virtue of their hybrid nature. The difference between online and offline should not be considered only in terms of the quantitative aspects related to the higher communication bandwidth that physical proximity entails (if for no other reason than because also body language and proxemics come into play); but also on a qualitative level, because offline interactions can act as potential triggers for a more complex and deeper involvement and relationships among the community members, that is not mediated by simply the linguistic medium. However, also the opposite influence can occur: Internet use can strengthen social contact, community engagement and attachment (Kavanaugh et al. 2005) and transform the physical community into a more integrated network community (Wellman et al. 2002). This is why in Figure 1 we considered the transition from purely either online or offline interaction to a hybrid interaction as an indicator of the positive evolution and maturation of a community.

When the social interactions allow people to achieve engagement in, draw pleasure from, and take enjoyment in the intentional and goal-oriented participation in the same -possibly co-located- conversations and tasks, we speak of conviviality (see Figure 1), giving this term a specific meaning within the community informatics discourse. We conceive this concept as a further level of community affordance, that is a condition that is made possible or even being promoted by conscious, voluntary and convinced membership in a community if some facilitating preconditions exist. Operationally, we also say that conviviality can be achieved by the members of a community that get acquainted with each other through engagement in the same activities, in the pursuit of personal and community welfare. In other words, it encompasses sociality and cooperativity, but it also places the experience of these dimensions within a context of gratification and satisfaction (see Figure 1).

The term 'conviviality' has been used several times in different scholarly contexts in the last forty years, especially in sociology, usually by relating it to a "set of positive relations between the people and the groups that form a society, with an emphasis on community life and equality rather than hierarchical functions" (Caire, 2010). In this effort, scholars have stuck to the traditional and literal meaning of the word more or less closely. In fact, dictionaries usually refer this term to what pertains to "social events where people can eat, drink, and talk in a friendly way with others" (cf. Merrian Webster 2014). As rightly noted by Schechter (2004), conviviality "in a basic sense" is to be seen as but "a social form of human interaction". Also Caire and Schechter noticed that the social interaction should be intended as purposefully aimed at "reinforcing group cohesion through the recognition of common values" (Caire, 2010) "through a positive feeling of togetherness (being included in/or part of the group), on which the community's awareness of its identity is based." (Schechter, 2004). In this line, also Polanyi (2012) in 1974 denoted a community as "convivial" when it aims to share knowledge; as Caire and van der Torre (2010) summarizes in regard to this point: conviviality in a community entails that its "members trust each other, share commitments and interests and make mutual efforts to build conviviality and preserve it" (our emphasis).

The twofold idea that conviviality is something more than just socializing or getting involved in the same cooperative effort and that it regards valuable knowledge that is developed and circulated in social practices (Cabitza et al., 2014) is a starting position that is close to the one proposed by Illich (1973) in the 1970s to refer to an ideal value and condition where the individuals' creativity, imagination, and energy are maximized while their freedom is realized not in spite of, but rather in virtue of "personal interdependence" (Caire, 2010). This concept has then be retaken by Putnam (1988) in the 80's as an "enhancement" to his theory on "social capital" and a "condition for civil society"; to be then more recently reformulated in the context of urban communities by authors like Gilroy (2004) and Peattie (1998), who defined conviviality as a set of "small-group rituals and social bonding in serious collective action" (p. 246), Lamizet (2004), who defined it as both "institutional structures that facilitate social relations and technological processes that are easy to control and pleasurable to use", and by Caire (2009) in the context of smart cities, where conviviality was seen as "a mechanism to reinforce social cohesion and as a tool to reduce mis-coordinations between individuals".

We propose to focus on the concept of conviviality in the same mould as the authors mentioned above. However, differently from the literal meaning of the word and some of the past contributions, we propose to avoid speaking of conviviality (in technical terms) when this can be reduced to the "jolly hanging out" of peers in some common social occurrence. On the contrary, we stress the role of the personal enjoyment and engagement of most of the members of a convivial community in being part of a common enterprise and open-ended accomplishment. This means we present conviviality as an emerging collective property of a community, which nevertheless is composed by individual feelings, that is a condition their members can enjoy and exhibit in a perceivable (observable) way. In Figure 1 we denoted the necessary "ingredient" to have conviviality when either sociality or cooperativity (or both) has been established within a community with the Greek letter epsilon. This is done for a twofold reason: first of all, this ineffable element can be of relatively small extent or scope like the small positive quantities mentioned in mathematical calculus, but yet present, in any relevant form. Second, when thinkers have started to pinpoint this dimension in their reflections on the welfare of communities and the nature of social human relationships, they have historically thought of Greek terms starting with epsilon, like eudaimonia (that is happiness, welfare, human flourishing, good spirit) and eutrapelia (in Latin, urbanitas, defined by Illich, 1973 "graceful playfulness in personal relatedness", p. 7): these are all terms connected with the idea of civic friendship that, according to Aristotle, is the foundation of the polis, what holds communities together, and what through which citizens can partake in the good life (Pangle, 2006).

Linking conviviality to a condition that cannot be reduced to any form, however complex, of sociality or cooperation alone has two immediate consequences on how to derive and use the construct for the design of networking technologies.

First, conviviality in communities (as an analytical construct) can be measured: this can be done by assessing it through a number of equally valid, reliable and standard psychometric tools that address a number of correlated dimensions, like subjective well-being, life satisfaction and happiness (Kahneman & Krueger, 2006) of their members or, the other way round, their self-rated anxiety or depression (Bagby et al, 2014). In the literature there are a number of rating scales that in community psychology and related disciplines have been validated to assess "social engagement", "enjoyment in social activities" (e.g., the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory by Ryan et al., 2008), social participation and community integration (Sander et al., 2010). In a user study that we are currently conducting in the context of network communities of place (where place is circumscribed in the same city area or neighborhood) we have administered to hundreds of social media users a multidimensional questionnaire combining together a short tool to evaluate the "attitude to exchange" and three standard assessment tools, the sense of community rating scale (MTSOC, Prezza et al., 2009) the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES, Scholz et al. 2002) and the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS, Diener et al. 1985): our idea is to contribute in defining a conviviality rating scale and validate it empirically in large-scale user studies.

Once individual constructs are represented by short sets of items, partial or global cumulative scores can be obtained through standard statistical techniques to extract a quantitative, yet indicative indicator of the overall level of engagement and enjoyment in community activities. This allows us to compare trends either between different network communities (in cross-sectional studies) or in the same community over time (in longitudinal studies), as well as against relevant events like the introduction and adoption of new functionalities offered by the networking technology. This can be a convenient way to also assess the impact of the networking technology, as well as to prioritize changes to the application and initiatives of community promotion.

Although such a standard rating scale still does not exist, it should not be ruled out that such a contribution could come from the community informatics field sooner or later, in a multidisciplinary effort combining contributions from psychometrics (especially from the so called field of the psychology of well-being or positive psychology, cf. Huppert et al. 2005), user-centered informatics and community studies (that is an academic field drawing on both sociology and anthropology and the social research methods of ethnography in studying communities).

The application of psychometric tools to the members of a community could be used in either confirming or rejecting hypotheses on the involvement in the community and impact of this latter on the quality of their life. For instance, it can be argued that conviviality is a phenomenon that is more frequently or clearly observed when the members of a network community used to meet in the physical world on a stable basis; or that getting also involved with conscious commitment in cooperative tasks whose goals have been set collaboratively is another contributing factor for conviviality: in the same vein, Wenger (1998) speaks of the "joint enterprise" to create a positive organizational atmosphere that could "convey a sense of familiar conviviality" (p. 24) for the effect this latter can have on the value produced by the "mutual engagement" of the community members. Alternatively, one could conjecture that conviviality is more likely to occur, or emerge, in those network communities that exhibit typical traits of communities of intent, communities of knowledge, or communities of practice (see above) rather than in communities bound together just by common intents, concerns, interests and place. This could be because the voluntary nature of the coming together of the members of these kinds of community, and the gratuitous efforts usually paid for either its own sake, or the feeling to contribute to the community's welfare are the elements that, yet hard to detect and assess (Schmidt, 2011), make a collaborative effort a positive experience, potentially enriching the actors involved.

In the same way, it could be argued on a scientific ground that current social networking sites still fall short of creating conviviality-facilitating conditions, in the apparent paradox of highly facilitating connectivity (a precondition for communication, see Table 1), but also surrogating and potentially de-empowering real-world relationships (cf. Kraut et al. 1998; Wästlund, 2001; Turkle, 2012). This latter hypothesis could be related to the growing number of studies providing some evidence that the use of social networking sites, especially Facebook, is associated with typically socially destructive feelings (Ryan, T. and Xenos, 2011), like jealousy (Muise et al., 2009), frustration (Chou and Edge, 2012), and envy (Krasnova et al., 2013, Tandoc et al, 2015); with narcissism (Mehdizadeh, 2010) and histrionic personality disorders (Rosen et al. 2013); with the perception of low relative social value (Blease, 2015) and social trust (Sabatini and Sarracino, 2014); with depression (Moreno et al. 2011); with a decrease in subjective well-being over time (Sabatini and Sarracino, 2014; Verduyn et al., 2015) and even in the overall quality of life (Kross et al., 2013).

Nevertheless, irrespective of the specific conjecture on what facilitates or hampers conviviality in communities, further user studies and research in this strand could either prove or reject them and foster a debate that is useful to the development and experimentation of novel networking technologies.

Second consequence: conviviality relates to the quality of the relationships occurring between community members and between them and the social structure to which they feel they belong. This means that, differently from communication and cooperation (which are both interaction modes and the virtuous conditions these allow to achieve, as reported in Table 1) it is difficult (or plainly wrong) to think of conviviality in terms of supportive functionalities, and conviviality can be neither guaranteed nor maintained by any networking technology per se. Nevertheless, we believe it should be considered one of the most important potential conditions to afford within a community and that its elusive nature should neither worry nor puzzle the designers of networking technologies, at least not any more than the discourse on User Experience (UX) should, in its relationship with the usability discourse. A short digression on the parallel between usability and sociability (Preece, 2001) and UX and conviviality should make this last point clear.

Usability is concerned with how intuitive and easy it is for the users of technology to learn to use and interact with a product (Preece, 2001). A "new genre" or "component", in Preece's words, of usability, that she called sociability, specifies this concept in regard to "how members of a community interact with each other via the supporting technology" (ibid. p. 351): sociability then regards how intuitive and easy it is for the members of a network communities to interact with others via the networking technology, that is how such a technology is easy to use for users to communicate and cooperate with each other. For its close relationship with the concept of usability, indicators of good sociability have been enumerated mainly on the quantitative side and with an emphasis on community performance: the number of participants in the community; the number of messages; the number of messages per participant; how much reciprocity, indicated by the number of responses per participant; the amount of on-topic discussion; the number and type of incidents that produce uncivil behavior; average duration of membership and so forth (Preece, 2001).

Once the concept of usability has strengthened in the literature and professional practice,, the concept of "User Experience" (UX) has then been proposed to go beyond its functional and non-functional aspects, i.e., instrumental and performance-related, to "look at the individual's entire interaction [...] as well as the thoughts, feelings and perceptions that result from that interaction" (Albert & Tullis, 2013, p. 5). Thus, UX focuses on the satisfaction component of usability, and on the user' perceptions and responses (cf. the ISO definition), including emotions like pleasure, delight, joy and fun (Bargas-Avila & Hornbæk, 2011). In the same manner as Preece has derived the concept of sociability from that of usability, we can consider conviviality related to UX, that is to the extension of the individual dimension of the emotional response to the social dimension, and hence related to recent studies focusing on UX "in the social" (cf. the concept of co-experience, Battarbee and Koskinen, 2005) where authors speak of delightful, joyful or "good social experience", which has a potential to "inspire behavioural and emotional change" (Hassenzahl & Tractinsky, 2006). As UX requires ethnographic and psychometric methods to be evaluated (Albert & Tullis, 2013), the same holds for conviviality. As UX is difficult to be enframed in specific requirements (differently from usability) and it is said to be related to "hedonic, affective or experiential aspects of technology use" (Hassenzahl & Tractinsky, 2006), also conviviality can be related to the hedonic, emotional, affective or experiential aspects of human-human interaction and be therefore better characterized by principles to consider in the design of a specific class of artifacts, as we will see in the last section.

CONVIVIAL ARTIFACTS

We ground our idea of convivial artifact on similar ideas recently outlined by other researchers interested in urban planning (e.g., (Banerjee, 2001)) and in the design of ICTs supporting urban communities (Antoniadis and Apostol, 2013). In this line, we believe that to design "tools for conviviality" is different than designing for sociability only, which in some way is related to the augmentation of the "communicative side" of sociality, and that it is also different from designing for collaboration in organizational domains, where structured patterns, protocols and coordinative conventions exist (Schmidt and Bannon, 1992; Schmidt, 2011).

The expression "convivial tool" was first used by Illich (1973), who spoke of conviviality just to introduce this particular class of tools, and consequently the societies where these tools are used (Illich, 1973). In his work he made a clear reference to the Latin root of the word - con-vivium (to live together, and only after to have a nice time together) - and characterized a convivial tool as a tool specifically designed to unite people, in both its production, use and continuous accommodation (Harris and Henderson, 1999), which would not alienate them, and indeed would give them opportunities to enjoy life together. Furthermore in Illich's words, convivial tools are "responsibly limited [...] modern technologies [that] serve politically interrelated individuals rather than managers [and corporate profit-related aims]". More precisely, Illich defined a convivial tool as "that which gives each person who uses it the greatest opportunity to enrich the environment with the fruits of his or her vision": it is therefore a tool empowering the user and giving her both voice and the opportunity to have an impact on her world; and a tool whose "renewal would be as unpredictable, creative, and lively as the people who use them" (Illich, 1973), so envisioning "in nuce" the affordance that has been called authoring in the previous section.

In light of Illich's seminal contribution, and coherently with the technical definition of conviviality we discussed in the previous section, we define convivial artifact as any technology (and the related technique of use and exploitation) that either allows or facilitates (cf. the concept of affordance) people to experience life within a community as a convivial (i.e., pleasing, gratifying, edifying, self-fulfilling, self-expressive, etc.) experience. Convivial artifacts are then a class of artifacts that are aimed at promoting sociality, cooperativity, self-expression and autonomous and creative intercourses among individuals, and therefore both communication, and what adds to this latter dimension the will to act together, that is collective deliberation, collective planning, and cooperative action (Nowicka and Vertovec, 2013) aimed at reaching purposes collectively set by means of lines of action collectively agreed upon (see Table 1).

To denote an artifact as convivial requires both an intended and explicit aim of the artifact (i.e., supporting behaviors in a community that can be traced back to the conviviality spectrum); and a post-hoc verification of the positive impact of the artifact on the related subjective dimensions of the members involved, through one (or more) tools like the ones mentioned above.

In regard to the first criterion, examples abound: social media supporting the exchange or co-production of value, like those by which people can collect requests and distribute commodities within ethical purchasing groups (Mezzacapo, 2014); or organize and manage local exchange communities, like time banks (Bellotti et al. 2014) or borrow-and-loan groups (of which also reading groups and "diffuse libraries" are common instances), and the activities of voluntary associations are all means that exploit the "communicative side" of social media to connect and link people together, but then go beyond that side, to enable both online and offline collaboration and joint action. As Antoniadis and Apostol (2013) also argue, "sharing information with neighbours is a critical requirement for creating convivial physical, and not virtual, communities and for a more informed and cohesive participation in public affairs" (our emphasis).

In this light, the anti-conviviality of social media like Facebook is summarized by Antoniadis and Apostol (2014), by enumerating a number of critical points: these tools "exclude those that do not have a Facebook account and/or Internet access"; they influence the "collective image" of the communities that choose that platform to gather and socialize; and do this through "numerous small but important design details [that are] externally decided [and imposed to the users, and are] exactly the same [...] for all places in the world, such as ] the presentation order of the various posts and the moderation rights of the administrator, the level of anonymity allowed, the permanence of the recorded information over time, and the user interface such as wording, colours and menu items" (Antoniadis and Apostol, 2014); and, finally the corporates behind these tools own all the information generated therein and generally exploit it "for commercial or other purposes, raising serious threats related to privacy, surveillance, and censorship." Similarly, we had the opportunity to talk with the founders and administrators of some of the most successful Facebook groups that are administered according to the "Social Street" manifesto and guidelines , and that have recently gained great attention from the Italian mass media: in these interviews and talks, we found people generally enthusiastic about their initiative, but also realistically wary of the capability of a sociality-oriented social media such as Facebook to support people engagement in constant, not sporadic, collaborative tasks.

Related to this latter point and also to the second criterion by which to rightly deem a technology as convivial, we advocate more new research aimed at validating both the sociability and conviviality of the social media adopted by a community, and at assessing the satisfaction by which communication- and cooperation-oriented functionalities are exploited by the members of the community for the creation and improvement of the community social value (i.e., social capital, trust, members' wellbeing, etc.): briefly put, an assessment of the level of conviviality reached by the network community with the psychometric tools mentioned above.

Design principles for convivial artifacts

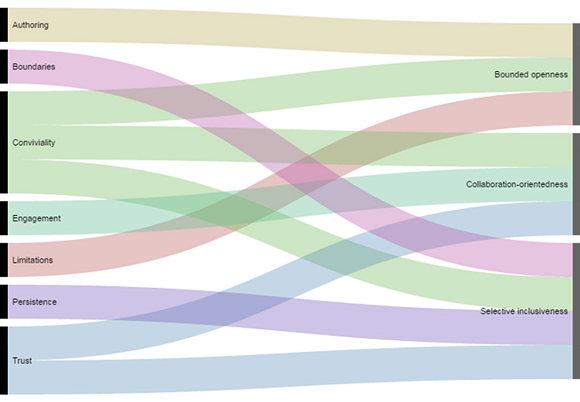

These considerations shed light on a potential set of high-level principles that could inform the design of convivial artifacts. Obviously, following these principles does not guarantee the building of a convivial artifact, especially according to the experiential dimension of the second criterion mentioned above; nevertheless, so doing would help prioritize specific areas of improvement and investment in related functional and non-functional requirements. In what follows we draw a first tentative list of these principles, which can be mapped into the community affordances discussed above (see Figure 2). This list is just a first step on which we advocate further research from the Communities & Technologies field to identify more fine-grained requirements. This effort would go in the same mould of the work by Caire (2010), who observed that the requirements for convivial tools should include: the sharing of knowledge and skills (how to accomplish and promote this exchange); the dealing with conflict (how to minimize it, how to cope with it once it bursts out); and the feeling of 'togetherness' and belonging to the same community (similarly to our agenda, how to promote and evaluate it). Our principles are:

- Collaboration-orientedness. A convivial digital tool should support (and in some cases even enable) collaborative tasks, not just chattering: this means to go beyond (in an inclusive manner) the "social networking" model of communication a la` Facebook (Cabitza and Cornetta, 2014), which basically entails a common artifact where people create connections (their "social network"), and share with acquaintances their preferences, messages, information on events, and various content, but usually do not co-create content (as, e.g., in the Google Doc platform). This does not mean that we underestimate the potential of technology-mediated communication to allow a motivated group of people to achieve important results collaboratively. We are just stressing the important limitation that is entailed by believing that only communication could be effectively supported by technology, and "the rest will follow". As is widely known in the CSCW community since its beginning, affording communication is simply not enough to promote collaboration (Grudin, 1988). To move beyond this, it is necessary to conceive systems that also provide task-specific value, such as services to promote informal and emergent economies based on sharing and coproduction, as for example ethical purchasing groups, used goods exchange communities, time banks, book-and-thing loan groups. This can be done by integrating together functions like those provided by different services that are nowadays quite scattered in the Internet, as for example through Doodle1 and Meetup2 to organize meetings; i-petitions3 and livepetitions4 , to aggregate consensus and sensitize people around a specific topic; Everyblock5 , to aggregate and discuss local news and information, such as "local photos posted to Flickr, user reviews of local businesses on Yelp, lost-and-found postings from Craigslist" 6 , and many other vertical systems to organize used stuff exchanges, barter associations, shareable goods inventories, time banks and other kinds of community exchange systems (e.g., Streetbank7 , Frecycle8 , Neighborgoods9 and, in Italy, Locloc10 , Sfinz11 and Superfred12 .) These goal-oriented components could motivate the physical aggregation of people, and their re-appropriation of common spaces in the local territory that they inhabit. For instance, in the Condiviviamo project`3 , we developed a Drupal-based module by which to enable the construction and management of a collective and diffuse (i.e, distributed) library14 . This library is constituted of all of the books shared by the citizens living in the same neighborhood, and willing to lend their own books in exchange of the right to borrow those of others. The service is intended to help interested users index and expose their books, search among all the books so collected, keep track of current loans, send timely reminders, and the like but, above all, to organize encounters for handing over the books physically, seen as an opportunity for lenders and borrowers to get to know each other and comment on their common readings. The potential for conviviality of these services lies in the fact that these systems support the organization of real encounters in the physical world, and therefore that they are also aimed at promoting their non-use (Cabitza, 2014b), that is the condition in which the user can do without the technology sooner or later and feel comfortable in quitting its use (exactly like meetup, after all) or even abandoning it.bounded openness. This principle can be articulated in two different, but somehow related, levels of analysis. First, we can consider it from a functional and operational point of view. This means that the convivial artifact should be open-source, non-profit, and provide a modular set of components where most of the community members should be able to choose among some possibilities and configure by themselves (or at least understand the available options and vote for a specific configuration): most current Content Management Systems, like Drupal or Joomla, are already highly modular and allow for the incremental enrichment of their basic social features. Thus, bounded openness regards the capability of a system to be "opened" and appropriated also by means of hard tinkering and ad-hoc development, beside a large amount of potential alternative configurations that have been predefined by the original developers of the platform (cf. bounded). This would allow the platform to be customized to a great extent, or accommodated in the words of Harris and Henderson (1999) to the community's needs, and yet not been perceived as open as a city square, but rather as a particular home, which is furnished and decorated to its inhabitants' will and taste. Appropriation and domestication are important processes to make community shelters more familiar to their inhabitants, even when these shelters are but "virtual", as social media are. In fact, in existing social networking sites, users produce all (or most of the) content. But, as also noticed by Antoniadis and Apostol (2014) the commands to produce this content, and the structures through which to "consume" it, even the ways to share it (i.e., across what platforms, with which limitations) are imposed from above and subject to change with no notice or consultation (cf. the introduction of the Timeline in Facebook). This contributes to undermining the feeling of being in common virtual place; it corroborates the idea of being guests of some host that houses you (probably just to observe you, or take some opportunity to sell you something); and above all, it totally stifles the community affordance of authoring. For these reasons, we also advocate the possibility that the most IT-skilled members of the local community adopt a convivial artifact able to extend the baseline platform with "contributed modules" or to adapt existing extensions developed by the community of other developers, possibly by "branching out" the standard profile and distribution, as it is usual practice in the developer' communities of the successful open-source platforms. The same phenomenon has been described by Gaved and Mulholland (2010) and denoted with the phrase "grassroots (initiated) networked communities": in these communities the networking platform is in the full control of the community members, and not something that some private for-profit corporation makes available to them, usually with a business model based on advertising, user profiling, and more or less direct product selling and brand promotion. On a second level of description, we characterized the concept of bounded openness also in other terms (Cabitza et al., 2013) to stress how the symbolic and textual representations have to be managed to be sufficiently "malleable" to any real context, that is the support must adopt open-ended terminology defined in a bottom-up fashion, while of course avoiding the Babel tower drift. More concretely, this kind of openness means that a convivial artifact should let users associate the occurrence of certain symbols, or configurations of signs, with application behaviors that do not change irreversibly the state of the system; or if they change it, they also provide an explicit indication of what relation symbol-command has been activated, and why (i.e., on the basis of what rule or operationalized convention). In this mould, we have begun investigating how lightweight functions such as side annotations could be realized to reflect and promote the local and extempore conventions of the users involved while avoiding the risk of pinpointing and freezing them "hardwired" to the application logic of the system (Cabitza et al., 2009; Cabitza and Simone, 2012).

- Selective inclusiveness. Within a community, boundaries can be necessary for the identity of the social structure that recognizes itself within those boundaries. However, boundaries also contribute to creating an "inside" and an "outside", which is the basis for any discrimination and for the specific process by which even conviviality can turn into a "mask [of] the power relationships and social structures that govern communities" (Caire, 2010) after Taylor), and can be "achieved for the majority, but only through a process by which non-conviviality is reinforced for the minority" (Ashby, 2004). For this reason, the platform should not encourage the idea of communities as self-standing entities. rather, it should promote the conceptual arbitrariness and pragmatic convenience of any division in human ensembles, by enacting a mechanism by which the community creates (and maintains) sharing policies that allow for multiple overlapping subsets of the whole community that include people with common concerns on the basis of multiple criteria. In the open-source Drupal-based project mentioned above, condiviviamo, we call these community subsets incommunities (or accomunità in Italian) as these groups are ways to (virtually) gather together people with something "in-common". Examples of incommunities abound: people living in the same floor of the same building, or in the same unit or wing of this latter (which usually encompass several floors); the board of the directors of a single condominium; the group of apartment owners; the people working in a specific building; the people living in the same street, or (of course) in the same neighborhood and (or) city area; people going to the same school (in a specific street) or working for companies located therein. In short, an incommunity is any group of people having some characteristic that is valuable for the producer of the content to be shared. Notably, this characteristic can also be highly dynamic, volatile and defined withn the system on-the-fly, as in the case of the incommunity that encompasses all of the people within a 5-minute walk or within a mile of where the content producer is "now". The concept of incommunity mirrors that of "circle", which was first proposed by Adams (Adams, 2012) and then adopted (and widely popularized) by the Google Plus platform; however it also differs from this idea in two aspects: first incommunities are defined by the community itself (new incommunities are proposed by the people, but then consolidated only on a collective agreement basis); second, when a content is shared in some incommunity, that is when a member of multiple incommunities shares a content with the other members of (some of) these incommunities, an explicit operation of intersection is available, and it is indeed the default option (that is, the content is shared with the members that belong to all of the incommunities mentioned). The same goes for the access to the other services of the platform15 , as this latter should be able to route both content elements and available operations on the basis of community membership. Obviously the mechanism of the incommunity is just an example of how a convivial artifact could address the requirement of selective inclusiveness. Much further research is needed to assess how people in real communities would want to adopt this "variable geometry" sharing mechanism and appropriate this more articulated notion of "circle" for their situated needs and aims.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper has proposed a set of sensitizing concepts in terms of affordances that a network community and its technological infrastructure should offer to its members; in regard to the community affordances we did this by revisiting and extending the set of sensitizing concepts originally proposed in (Mynatt et al., 1998). We also introduced the affordances of trust and conviviality and discussed the latter one to some extent in light of several previous research contributions by seeing it as an important facet of community interaction. Affording conviviality within network communities requires reflecting on how supportive technologies, what we denote with the general expression of "convivial artifacts", have to be conceived. To this aim, we have made the point that there is a need to explore new dimensions along which communication- and cooperation-oriented functionalities can be combined to better support sociality and cooperativity within network communities, and thus go beyond what we called the "Facebook model of socialization". This model is mainly, if not exclusively, based on self-image projection, self-representation and communication (Zhao et al., 2013) and its evolution would entail a stronger focus on cooperation-oriented support (see Table 1), as a necessary, but far from sufficient, precondition to get the community members to enjoy conviviality in their social interactions and activities.

The paper also proposes an initial set of three principles that should inform the design of convivial artifacts. All of them go in the direction of allowing community members to be in full control of the artifacts they are using to support their communication and cooperation, with a minimum set of restrictions that are imposed by the networking technology. This means that the members of a network community should be put in the position of playing their preferred role (more or less active) to contribute in making the community itself a pleasant "environment" where to live, through their preferred level of mutual engagement and technology appropriation. This vision sheds light on the conception of technological platforms for various kinds of communities that we are currently developing and validating in the field.

The points discussed above motivate our focus on conviviality in our vision for the future of community-supporting technologies. As designers of artifacts that are shared and used within a community for its welfare, we have proposed the concept of conviviality as an operational parallel of similar concepts in the UX discourse, as delight, self-expression and pleasure: in the UX domain these concepts apply to the interaction with technology and related services and extend usability concerns; on the other hand, in community informatics we propose conviviality so as to extend sociability: that is, for its connections with the concepts of social interaction, community life and co-interaction, we propose to measure it on collective psychometric dimensions as a multidisciplinary approach to technology design, adjustment and evolution. In an even more ambitious perspective, the paper aims to contribute to the construction of a conceptual ground where the outcomes of the research regarding the interplay between communities and technology can be interpreted and characterized, compared and validated; in so doing, we believe that a common ground on these themes can be established within a mature research community which is able to overcome the fruitless contraposition between theory and practice.

ENDNOTES

1 doodle.com

2 www.meetup.com

3 www.ipetitions.com

4 livepetitions.org

5 www.everyblock.com

6 from the Everyblock description.

7 www.streetbank.com

8 www.freecycle.org

9 www.neighborgoods.net

10 www.locoloc.net

11 www.sfinz.com

12 superfred.it

13 www.condiviviamo.net

14 To this regard, we recall that Illich

considered "the library [as] the prototype of a convivial

tool".

15 We describe the services currently

on development and the ones planned in the project

showcase Web site, at http://www.condiviviamo.net and on

drupal.org.