Exploring E-Participation in the City of Cape Town

- Research Fellow, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, South Africa. Email: labanbagui@gmail.com

- Adjunct Professor of Information Management, Faculty of Informatics and Design, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, South Africa. Email: andy.bytheway@gmail.com

1. INTRODUCTION

The South African 1996 constitution has provided for a representative, deliberative and participative democracy. The constitution emphasises the participation of all people in government at all levels, because its aim is to repair the errors of the past and to create a more just, equal, and peaceful country (Republic of South Africa, 1996).

The government is organised around three spheres or levels of legislation: national, provincial and local representation. All spheres have legislative powers, from national to local, and respectively enact acts of Parliament, provincial acts and bylaws.

The South African scheme for public participation, whereby the needs of communities should actually be heard, was designed after the example of the Brazilian city of Porto Alegre, where the process was run at the level of the municipalities - as close as possible to the citizen (Department of Provincial and Local Government, 2007). Some progress has been achieved in South Africa. For example, at the transactional level it is possible to deal with corporate and personal tax issues on-line, and there is increasing use of text messages to inform citizens in different ways using their cell phones.

However, at a time when public disorder is rising, and the citizens of the country are feeling more and more ignored by their government (Piper & von Lieres, 2008), the country desperately needs more effective public participation (Republic of South Africa, 1998; RSA COGTA, 2009:34; Carrim, 2010). At the same time, the adoption and use of new technologies by citizens is rising rapidly.

This paper uses Actor Network Theory (ANT) in an analysis of an exploration of the use of mobile, web and social media technologies in achieving e-participation in the city of Cape Town.

The paper continues with a presentation of the city of Cape Town, a review of e-participation, methodology, the translation of e-participation in the city of Cape Town, and a discussion of the findings followed by a conclusion.

2. THE CITY OF CAPE TOWN

The city of Cape Town is the largest metropolis in the Western Cape Province. The city is a cosmopolitan place with communities of all races, religions, and languages; with various levels of education, earnings and wealth. The city is divided into 24 Subcouncils and 111 Wards. This study has chosen to look only at Subcouncils 17 and 16 within the boundaries defined in 2006 (Polack, 2011b). This choice was motivated by representation (they include most variations of culture and lifestyle that exist within the city), and accessibility within the limits of the project resources.

Cape Town's 2006 GGP (Gross Geographic Product), defined as the final value of all goods and services produced by the city in one year, is R123 582 million. Economic growth (the yearly percentage change in GGP) of 6% was achieved in 2006 (City of Cape Town, 2010a).

Cape Town (City of Cape Town - SDI/GIS, 2008) can be divided into two major types of community arising from the Apartheid era: previously underprivileged and poor areas (very much represented in Subcouncil 17); and previously privileged and wealthy areas (very well represented in Subcouncil 16).

Over 90% of the Western Cape Province population lives in the City of whom 52% are female and 48% are male. Around 50% are coloured, 35% are black, 10% are white and 5% are Indian or Asian (Statistics SA, 2010). In addition, there are communities of foreign nationals of unknown numbers.

The place of the individual within the city's framework is such that his/her voice must go through many bureaucratic layers before it reaches the decision-making table (City of Cape Town, n.d).

This section continues with a depiction of two socially representative subcouncils of the City.

2.1 Goodhope or Cape Town Subcouncil 16

Goodhope (Subcouncil 16) includes Wards 54, 74 and 77. The area was a white only zone during the Apartheid era and is still trying to manage the inherited stigma of the District Six removal. The area is the most densely populated of all the Subcouncils and hosts the seats of the Parliament of South Africa, the Provincial Government of the Western Cape and the local government of the City of Cape Town. This Subcouncil includes the core of the city's business hub where thousands of people come to work every day in a broad range of industries including banking, hospitality, filming and events.

There are also numerous community-based organisations including the Camps Bay Rate Payers Association (http://campsbayratepayers.blogspot.com/), Long Street Residents Association (LSRA), Central City Improvement District (CCID), and many more political organisations as present in council. There are also mosques, churches and temples.

2.2 Athlone and Districts or Cape Town Subcouncil 17

Athlone and District or Subcouncil 17 includes Wards 46, 47, 48, 49, 52 and 60. It is mainly inhabited by "coloured people" in an uncharacteristic mix of communities, cultures and peoples. The Subcouncil is part of the "Cape Flats" that was populated with displaced "District Six" inhabitants during the apartheid era. There are descendants of indigenous Khoe and San people, and also of Indians, Malaysian, Chinese, Bantu and Caucasian origin.

The area is problematic with social disintegration effects including: family breakdowns, single parenthood, breakdown of the authority of parents and teachers, high unemployment and unemployability rates, high crime and violence rates, substances abuses, despair and acceptance of a victimised image (Ramphele, 1991; Wachira, 2009:1-13).

Speaking of the effect of social disintegration in this area, Amanda Dissel (1997) cites Don Pinnock (1996), arguing that young people join criminal gangs to fulfil a need for a rite of passage which is lacking in their post-apartheid environment. In the past, traditional societies provided these rites to create a sense of direction, social acceptance and importance for the group:

"They create structures and rituals that work for them, carve their names into the ghetto walls and the language of popular culture, arm themselves with fearsome weapons and demand at gun-point what they cannot win with individual respect." (Pinnock, 1996:13)

The community has responded to the situation by generating and collaborating with organisations well-known from the city authorities including:

- Impact Direct Ministries (IDM) (http://www.impactdirect.org.za/), Themba Care (http://thembacareathlone.blogspot.com/), the Rlab (http://www.rlabs.org/), People Against Gangsterism and Drugs (PAGAD) (http://www.pagad.co.za/);

- Political organisations including DA, ANC and COPE;

- Mosques, churches and other temples.

2.3 The Mobile, Web and Social Media Channel in Cape Town

The Mobile, Web and Social media channel in Cape Town is approached by looking at the penetration of technology in communities, services available on networks and platforms used for interacting.

2.3.1 Penetration

According to Goldstuck and Wronski (2011), the penetration of Mobile, Web and Social media has deepened and the users' age curve has flattened to the extent that these channels have gone "mainstream". The use of mobile Web applications such as Mxit and BBM has surpassed experts' predictions. For example, Mxit (2012) claims more than 44 million registered users in South Africa, with 19% of them coming from the Western Cape.

2.3.2 Services

Cellular networks operators including Vodacom, MTN, Cell C, 8ta and Virgin Mobile offer a variety of services to customers; ranging from mobile telephony, SMS, USSD, Internet and Web access.

On top of that are service operators allowing individuals to interact with local government services online, for example to pay their electricity, water, traffic fines and other bills (e.g: https://www.ibuy.co.za/, http://www.ipay.co.za/, https://www.paycity.co.za/default.aspx, or https://www.energy.co.za/ ).

2.3.3 Platforms

Individuals in the city's communities interact with each other on social media applications including Mxit, BBM, AIM, or Facebook. They increasingly use Internet enabled devices (Goldstuck & Wronski, 2011).

2.4 The Government of the City of Cape Town and the Mobile Channel

This section paints a picture of the structure, the functioning and the purpose of the mobile channel of the local government of the city of Cape Town.

2.4.1 The Local Government of the City of Cape Town

A) The city council

The local government of the city of Cape Town is constituted of a City Council and an administration or executive management team.

The City Council is the legislative body responsible for the governance of Cape Town. That body makes and implements by-laws, the Integrated Development Plan (IDP), tariffs for rates/services and the annual budget, and also enters into service level agreements; in addition, it debates local government issues, ratifies or rejects proposals, acquires and disposes of capital assets, and appoints the Executive Mayor, the Executive Deputy Mayor and the City Manager. Decisions taken by the City Council are implemented by the City's executive management team. By-laws and policies are formulated and monitored by Council's portfolio committees which advise the council (Polack, 2011a).

The City Council is elected for 5 years and comprises 221 councillors, half of whom are Ward councillors and the rest are proportional representatives according to their political parties' strength. For the legislature that started in June 2011 and will end in June 2015, the city council seats are distributed amongst the most prominent political parties, dominated by the Democratic Alliance (DA) which holds 135 seats and the African National Congress (ANC) which holds 73 seats. Other smaller parties hold a smaller number of seats (Polack, 2011a).

The City Council is chaired by a Speaker who presides over meetings and oversees the process of public participations (Polack, 2011a).

B) The administration of the city

The city administration is double-headed with a political head called "Executive Mayoral Committee or MAYCO" supervised by the City's executive Mayor and an administrative head or executive management team organised in directorates under a City Manager. Typically, the composition of MAYCO changes more often than the management team. Directorates are very broad in scope and the one responsible for the department of Information Systems and Technology (IST) is Corporate Services. The IST department holds the largest budget of that directorate (City of Cape Town, 2011b).

The racial structure at staff levels of the city administration indicates that:

- 50% of staff are Coloured, 30% are African (black), 19% are White and 1% are Indian;

- within top and senior management, 50% are white, 30% are coloured, 19% are African and 1% are Indian (City of Cape Town, 2011:95).

These figures suggest that the strategic decision making in the city is racially dominated by whites.

C) Public protection

The community's last recourse in an argument with the City is the office of the city ombudsman (City of Cape Town, n.d) tasked to investigate and mediate residents' complaints about the municipality; also the office of the Public Protector and the Western Cape Public Protector, to advise on, investigate and redress improper and prejudicial conduct, maladministration and abuse of power in state affairs (Office of the Public Protector, n.d); finally there is the office of the Western Cape Consumer Protector. However, it is always possible to take legal advice from a lawyer, preferably a member of the Cape Bar Council (The Cape Bar Council, 2012) and to seek justice in court.

D) The city functioning

In understanding the functioning of local government in the city of Cape Town, a range of documents and sources, in addition to those already referenced above, is evidence of the relevant recent changes:

- The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (RSA,1996) is acclaimed as one of the most inclusive constitution in the African continent, guaranteeing equality of treatment for all South Africa's diverse population.

- Local Government: The municipal structure act 117 of 1998 provides for the establishment of municipality and their sub-divisions.

- Local Government: The municipal system act 32 of 2000 provides for the organisation and the functioning of municipalities so as to insure a sound achievement of public participation.

- Local Government: Municipal Electoral Act 27 of 2000 provides for election events for local government office.

- National policy framework for Public Participation (2007) encompasses legal community participation obligations of municipalities (Department of Provincial and Local Government, 2007:30)

- City of Cape Town cellular telecommunication infrastructure policy (City of Cape Town, 2002) provides for the control, development and installation of cellular telecommunication infrastructure in the city.

- City of Cape Town Language policy (2002b) provides for the fair and equal use of national languages on communication platforms including Websites in the city.

- City of Cape Town Public engagement policy (2009) provides regulation for means to be used for engaging with community members.

E) Participation in public participation

The city reported that 20 997 citizens were engaged in public participation in 2010 (Public Participation Unit, 2011). That number contrasts with the city's population of more than 3 million inhabitants (Statistic SA, 2010).

2.4.2 Cape Town Mobile, Web and Social Media Resources and Initiatives

The Government of Cape Town has chosen to invest heavily in information technology, following a "Smart City" strategy. An Enterprise Resource Planning system (ERP) has been deployed. Billing and procurement systems benefited significantly from the ERP; then a Geographic Information System (GIS) was incorporated to improve planning; human resource management (HR) was added; and a complaint notification system called the "C3 system" was plugged into the ERP system. Beyond the ERP implementation, the 'SmartCape' initiative put PCs in libraries for public use; the construction of a whole optical fibre network throughout the city is being undertaken (City of Cape Town, 2010; Odendaal, 2011); new safety systems to monitor and control crime are being implemented around toll free numbers, GIS, and other South African Police Service (SAPS) databases.

All these will impact highly on the provision of transactional services to citizens. But such innovations does not seem to contribute much to citizen's other needs such as for housing, sanitation, security, legal environment and other community infrastructural facilities. Do these innovations open efficient channels for public participation in government?

The local government of the city of Cape Town has also started to use mobile, Web and social media to communicate and engage with individuals and community organisations; that includes:

- SMS messages that are sent to Ward forum members and availability of toll free numbers around particular issues (e.g.: Water-related enquiries - contact 0860 103 089, send an e-mail to waterTOC@capetown.gov.za or send an SMS to 31373 open 24/7. (@cityofct, 24/02/2012)),

- An information rich Website at http://www.capetown.gov.za;

- A page on Facebook at http://www.facebook.com/pages/City-of-Cape-Town/113648061978937;

- An account on Twitter at https://twitter.com/#!/cityofct;

- A YouTube channel at http://www.youtube.com/user/cctecomm

This shows that these channels are now perceived by the City to be valuable in reaching out to individuals in communities.

3. E-PARTICIPATION IN GOVERNMENT

The combination of communications technology in business, communities, government and in the life of every individual makes an interesting mixture that challenges all our assumptions about our roles as consumers, employees, tax payers, public service recipients, or simply community members. That mixture opens up opportunities for all to participate in the governance of society as implied in this study of a case of representative democracy. Macintosh (2004) defines eDemocracy as:

"the use of information and communication technologies to engage citizens, support the democratic decision-making processes and strengthen representative democracy" (Macintosh, 2004:n.p).

Here the study chooses to use the term "e-participation" to place a clear focus on the engagement of citizens, and the role of communication technologies in engaging them. The following sections briefly review the literature concerning: e-participation research, e-participation stakeholders, and the mobile channel.

3.1 E-Participation Research

Public participation is complex, because the public can engage with government in many ways and at different levels. At one level - transactional - it is now possible to submit tax returns online and to pay traffic fines (to pick just two examples available in South Africa); at another - more strategic - it is possible to try and influence long term policy making by lobbying and voting online: these are elements reflecting e-participation activities.

E-participation is an emerging research field which according to Sanford and Rose (2007:410) derives its importance from:

- The participative imperative deduced from the right of all the stakeholders in society to participate in the formation and execution of public policy

- The instrumental justification, namely that it can be instrumental in more effective policy making and governance

- A technology focus:

"ICT has the potential to improve participation in the political process through: enhanced reach and range (inclusion); increased storage, analysis, presentation, and dissemination of contributions to the public policy and service debate; better management of scale; and by improvements to the process of organizing the public sphere debate" (Sanford & Rose, 2007:410).

In a review of the field, Sæbø, Rose and Flak (2008:417) shaped e-participation research around a narrative where e-participation actors (citizens, politicians, government institutions, voluntary organisations) conduct e-participation activities (online political discourse, eConsultation, eActivism, eCampaign, etc.), in the context of some factors (information availability, infrastructure, underlying technologies, accessibility, etc.), which result in certain effects (civic engagement, deliberative and democratic) determined through e-participation evaluation (quantity, demographics, and tone and style) allowing the improvement of e-participation activities. Theories and methods, here, are borrowed from related and already established research fields.

This depiction makes of the field more of an e-participation improvement effort thus limited to technicalities lightly considerate of outcomes such as development, environment preservation or peace. That framework was revisited by Medaglia (2012:348) who added "transparency and openness" as directions into e-participation evaluation type of research. This paper subscribes to that approach and to approaches that have in heart the outcome, and see e-participation as a means to an end. Henceforth, this study explores the network of actors meant to foster the achievement that e-participation promises.

The next section reviews selected prominent advances of e-participation in the world.

3.2 E-Participation Global Review

The closer we come to the actual formulation and implementation of government policy the more difficult it seems to influence anything. Early opinions concluded that "online citizen engagement in policy-making is new and examples of good practice are scarce" (OECD 2003). And it has been reported that more than half of all e-government projects fail (Heeks 2002).

However, experts have since suggested frameworks for assessing the quality of an implementation of e-government and thus of e-participation; and the prospect of success is still seen as very real (Andersen & Henriksen, 2006; Gupta & Jana, 2003; Heeks, 2006; Macintosh, 2006; UNDP, 2007; Tambouris et al., 2007; Thakur, 2009).

Of course, success can be seen from two perspectives. From the citizen's perspective success would comprise more appropriate services, more effectively delivered, at a lower cost to the individual. From the government's perspective, success might derive from these same things (where the views of the public carry some weight) but in other circumstances a government might have quite different ambitions - to consolidate its own power base and collect more tax revenue, whilst delivering fewer services at the lowest possible cost.

The European commission has funded numerous research projects within its boundaries with the objective of exploring, understanding and describing e-Participation initiatives or "efforts to broaden and deepen political participation by enabling citizens to connect with one another and with their elected representatives and governments, using ICTs" (Avdic et al., 2008; Tambouris et al., 2007).

The Democracy Network of Excellence or Demo-net is one of them. Demo-net brings deep insight into e-participation by providing research directions, research network, working definitions, case studies, first-hand findings, frameworks, models and pertaining theories (Avdic et al. 2008; Tambouris et al., 2007).

Other countries in the world have worked on e-government and recorded various results which impacted on e-participation. According to Dutta and Mia (2011) the ten countries with the best technology readiness are: Sweden, Singapore, Finland, Denmark, USA, Switzerland, Taiwan-China, Canada, Norway and Republic of Korea; the United Nations (UN, 2012:126) considers the best ten e-government countries to be: Republic of Korea, Netherlands, United Kingdom, Denmark, USA, France, Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Singapore. It is interesting to observe that some countries including Egypt, Kazakhstan or the Russian Federation with a lower technology readiness and with not an exactly effective e-government, rank rather high in their implementation of e-participation (UN, 2012:44).

Furthermore, the use of mobile, web and social media for e-participation translates in initiatives including monitoring some service delivery like with "Fixmystreet" (www.fixmystreet.com) websites present in many countries; neighbourhood watch against burglary (www.usaonwatch.org); offenders watch (www.watchsystems.com); e-Petitioning websites (www.e-petitioner.org.uk); data (www.opendatainitiative.org, data.worldbank.org) and open government (https://opendata.go.ke, opengovernmentinitiative.org) initiatives aiming at satisfying e-participation requirement of informing the public; and was crucial in spurring the Arab Spring (Anderson, 2011) in North Africa and the Middle-East.

3.3 E-Participation and E-Government in South Africa

3.3.1 Legal Environment and Institutions at National Level

In line with international trends and best practices, the government of South Africa has devised strategies and plans for all spheres and has started to adopt/enact eGovernment with laws, policies and standards on the acquisition and the use of ICT.

High level strategic objectives and directives aligned with the attainment of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) of the United Nations included the introduction of the notion of "developmental local government" in the core of the country's model of local government (Republic of South Africa, 1998); 'Batho Pele' (people first) principles were set forward to improve service delivery (DPSA, 1997); policies and frameworks established the environment within which IT is selected, acquired and used in government (Department of Public Service and Administration, 2001); the activation of constitutional provisions regarding access to information and the protection of certain information (Republic of South Africa, 2010:2) was enacted; regulations of electronic communication, transaction and applicable security (Republic of South Africa, 2002; Republic of South Africa, 2006) were also enacted.

State owned entities and bodies were created and other organs saw their prerogatives extended to carry through the strategy at all levels, including the Departments of Public Service and Administration, Local Government, Communications, Science and Technology, the Government Information Technology Office Council (GITOC), Electronic Communication Security (Pty) Ltd, the Universal Service and Access Agency of South Africa (USAASA), the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa, the ".za" Domain Name Authority (.za DNA) and the State Information Technology Agency (SITA) (Farelo & Morris, 2006; Department of Public Service and Administration, 2007; Department of Public Service and Administration 2008).

In addition, all government spheres have Websites and portals where a plethora of information is available to the public, for example: http://www.dpsa.gov.za, http://www.capegateway.gov.za and http://capetown.gov.za.

The network readiness rank of South Africa in the world has been assessed as 61st (Dutta & Mia, 2011) and its overall eGovernment index rank which was 97th in 2010 (UN, 2010) is now 101st with an e-Participation rank of 26th out of 32 groups (UN, 2012:126,134).

There are at least as many SIM cards in circulation as there are people. Mobile operators have implemented cutting edge services on their networks and cover all the populated parts of the country.

Hence there is a generally positive context within which to proceed with eGovernment and e-participation. It is not surprising therefore that researchers have already suggested ways of implementing m-Government to fit South African needs, all calling for a synergy of stakeholders (Maumbe & Owei, 2006).

3.3.2 E-Participation in the Western Cape Province: Strategies and Initiatives

One role of Provincial Government is to establish local government or municipalities and to take responsibility for major infrastructure within the boundaries of the province.

As early as 2001, the Western Cape Province started a move towards e-Government, initiating studies and devising strategies and plans (Provincial Government of the Western Cape, 2001; City of Cape Town & Provincial Government of the Western Cape, 2003).

The provincial e-Government (also called Cape Online strategy) has led to a range of projects for the development of a strong enabling footprint including: Cape Gateway, Cape view, Cape Change, Cape Net, and Cape Procure; also projects for connecting with online communities including Khanya (education), Elsenburg (Agriculture), Wesgro (Trade and investment), Western Cape Tourism and Cape Nature Conservation (Provincial Government of the Western Cape, 2001; City of Cape Town & Provincial Government of the Western Cape, 2003). All of these projects are either up and running or completed (for example the Cape Gateway or the Cape Procure) while others like the Cape Net are approaching maturity or are still growing. The initiation of an ambitious broadband strategy will enable further development.

In her state of the province address this year 2012, Premier Helen Zille reiterated a vision of the place of an inclusive provincial broadband strategy that will create the conditions needed for increased economic growth and jobs creation:

"Our broadband strategy will involve partnerships with a number of potential stakeholders, including licensed telecom service providers, commercial banks, the IDC and the DBSA, local businesses as well as local and national government. In other words, the roll-out of this broadband network exemplifies our "Better Together" approach. (Zille, 2012)"

In its effort to achieve a true "knowledge economy" the Provincial government of the Western Cape works with all the other spheres of government, businesses, communities, and with agencies such as SITA (to which it outsources most of its infrastructural work).

The city of Cape Town benefits from the Western Cape Provincial projects and e-Government infrastructural capabilities.

4. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The research question addressed here concerns the extent to which the use of mobile, web and social media helps or hinders e-participation in the city of Cape Town.

The methodology used follows a qualitative approach in line with its exploratory aim. Literature and document reviews, focus group and in-depth interviews provided valuable data and informed the development of an Actor Network Theory (ANT) analysis of the achievement of e-participation in the city of Cape Town, from which final results and conclusions were derived.

The study performed a literature and document review online and in libraries, following up on the trail of relevant information about the adoption and enactment of e-participation in the city of Cape Town.

The study also undertook 16 in-depth interviews and 1 focus group of local government officials and community members between October 2010 and March 2011. Respondents were all required to have a mobile phone and to be able afford the minimum cost expected for its maintenance; therefore they tended not to be the poorest within the community.

This paper considers e-participation as a socio-technical network constituted with humans (community members, councillors, line managers and agents of the city), structures (Citizen Based Organisations, Non-Governmental Organisations, city council, policies, and bylaws) and technology (mobile phones, the World Wide Web, social media and backend systems called here the mobile channel). e-participation translates the common interest of actors (here public participation stakeholders) to express their needs and opinions to the relevant governmental body, using the mobile channel.

5. ACTOR NETWORK THEORY AND E-PARTICIPATION

One way to explain the spreading of innovation, such as the adoption of e-participation using mobile, web and social media, is through the identification and recognition of the influential consortium of "actors" that instantiated the idea and carries it through. If innovation fails it can be argued that the primary actors involved in constructing the supporting network of alliances didn't succeed in stabilising the network (McMaster et al., 1997). This is the domain of Actor Network Theory (ANT), "the sociology of translation" (Law, 1992), a method of investigating socio-technical phenomenon. ANT was developed with the idea that knowledge lies within processes, systems and artefacts: social processes like consultation, conceptual systems like the structuration of e-participation within public participation, and material artefacts like the technological infrastructure that constitutes the mobile channel in e-participation (Callon, 1991; Latour, 1992). It considers agents, communities, organisations and machines as actors that interact within and by means of actor-networks.

In ANT, an actor is a human or nonhuman entity that is able to make its presence distinctively perceived by other actors of the network (Law, 1987). Actor-Networks here are heterogeneous networks of mutually constitutive resources and actors, ensuing with an actor being understood as being a network as well (Callon & Law, 1997). That particular characteristic has two facets:

- an actor can be thought of as a 'black box', the content of which need not be considered even though it might contain other networks or further complex intricacies (Callon, 1986);

- Similarly, a whole network can be 'Punctualised' into a single point, as an actor in the network, thereby masking its inherent complexities (Law, 1992).

ANT gives to the human and to the nonhuman the same analytical treatment (analytical impartiality), uses the same vocabulary in the process and allows or considers humans to associate or interact with nonhumans as if they were human, and vice versa: respectively it is built upon agnosticism, generalised symmetry and free association (Tatnall & Gilding, 1999). That approach implies that if applied to e-participation, in such a network:

- Individuals, local government and mobile, web and social media will be considered without party taking or judgment;

- humans (individuals in communities, in specialised organisation and in government) and nonhumans (community organisations, businesses, local governments, mobile phone or backend ICT infrastructure) should be regarded as being of the same abstract kind, they would be considered as actors and networks;

- Relationships can exist between human and nonhuman elements such as cellular phone, social network websites or the local government of Cape Town.

To illustrate this, the mobile channel suggested in this study would be able to charm a prospective participant into changing her or his behaviour and equally the prospective participant would be able to modify the channel to fit its preferences.

The network here is the context for a 'continually negotiated process' that maintains its cohesion and its existence. Actors are only considered in relation to, and not separated from, other actors or parts of the network. Networks are characterised by the degree of alignment of interests (common history and shared space), coordination (adoption of convention, codification, and translation regiments) and irreversibility of iterations of the network.

ANT defines the constitution of a network within a model of translation, comprising four principal moments or stages: Problematisation, Interessement, enrolment and mobilisation of allies (Callon 1986). Problematisation is a process that defines the problem to be solved by the emergence of the network. In this moment, key actors strive to delineate the nature of the problem and develop a solution to be implemented, for which they also determine the role of other actors. These key actors attempt to establish themselves as an 'Obligatory Passage Point' (OPP) which must be negotiated as part of the solution (Tatnall & Burgess, 2002).

E-participation strives to carry community needs through to local government decision makers in such a way that they can use it within the norms, regulations and capabilities under their control. Clearly, for all the technology that might assist, there will be a degree of negotiation and obligation involved.

Interessement is concerned with engaging with and imposing on other actors, identities and roles defined during the Problematisation. The processes here can be based on coercion or negotiated engagement from key actors, coming between the targeted actor and some others they were associated with, to redirect the interest of the targeted actor towards their own (Law, 1986).

Concerning e-participation, interessement would be about public awareness and engagement strategies, policies and initiatives around the use of mobile, web and social media technologies for e-participation, and a general jockeying for position between the actors in a context where concepts of power and influence are primary, but not always clearly understood and by no means stable in nature.

Enrolment sees aligned interests coming together. Acknowledging that roles were previously allocated and accepted, actors now set out to act upon them, leading to the institution of a stable network of alliances. The group of primary actors will grow accordingly, contributing towards the maintenance of that stability. Such a network or portion of a network can be considered a 'black box'.

e-participation roles are occupied in order to organise events, inform the public collect submissions, and inject them in the decision making process via available channels.

Mobilisation happens when a stable nucleus has formed around the proposed solution to the given problem. Actors are then encouraged to enrol yet others into the network. Hence, maintaining the alignment of interest remains of the utmost importance to prevent the opening of the 'black box', leading to the possible destruction of the network.

Experience in e-participation indicates that alignment of the key actors can easily lead to quite different kinds of success and failure, as seen by the different role players.

Within the ANT framework, innovation is 'translated', following an inertia generated by certain actors in the network (Tatnall & Gilding, 1999) and ANT looks at the formation of that network. The key question here is: what differences might eventuate in the case that mobile, web and social media technologies are used for e-participation?

6. CRITICS OF ANT AND ALTERNATIVES

ANT is subject to many critics including: limited analysis of social structures (loss of sight of the intricacies of social structures), problem description (detailed narrative issue), amoral stances (the agency and intentionality of nonhuman issue), and symmetrical treatment of human and nonhuman (Human and nonhuman comparability issue) (Walsham, 1997; Rose et al., 2005).

With these critics, it is tempting to think about using for instance Structuration Theory (Giddens, 1984) or Activity Theory (Engeström, 1999) instead of ANT. However, Structuration theory while suggesting a social ontology and allowing envisioning the inter-connexion of "structures" and "agents", falls short on research methodological recommendations (Rose & Scheepers, 2001); Activity Theory offers a framework for analysing an "activity" between a "subject" and an "object" but not the relationships between "activities". ANT permits filling these gaps by providing methodological principles and guidelines on investigating the contribution of technology (mobile, web and social media) into the production of an activity (e-participation) from the negotiated relationships between actors engaged in other activities and networks.

Walsham (1997) suggests being flexible in using ANT, by possibly drawing from structuration theory in order to mitigate the limitations in its analysis of social structures by keeping in mind that its focus is not morality but understanding of the socio-technical phenomenon and by considering its generalised symmetry as an analytical tool which has limitations but provides important insights.

This paper does not draw from alternatives suggested here, and uses ANT and all its components as analytical tools or lenses in its attempt to generate reliable and unbiased results.

7. RESPONDENTS' AND PARTICIPANTS' WORDS ON E-PARTICIPATION IN CAPE TOWN

The study accounted in this paper realised eleven in-depth interviews and one focus group. This included interviews of two community members in subcouncil 16 and a focus group of three individuals in subcouncil 17; and nine interviews of local government officials:

Bridgetown focus group: the focus group took place in Bridgetown with three participants recalled here as R1, R2 and R3. They are all smartphone users.

R99: Is a female journalist with very strong views, using a Smartphone

LSRA: Is an entrepreneur and a spokesperson for the Longs Street Residents Association - one of the most active and vocal community-based organisations within Cape Town. He owns a smartphone.

Council: Is a strong white and mature Afrikaner. He has an important position at the city council and doesn't show his cellular phone.

RL: Is a strong and mature coloured woman. She is a councillor and owns a very old mobile phone.

RC: Is a coloured man. He is a Subcouncil official in Athlone and district and owns a smartphone.

RW: Is a mature, energetic and smiling white woman. She is a member of the mayoral committee and owns a regular mobile phone.

RTA: Is a strong and mature white man, an Alderman at the Subcouncil 16 (Goodhope). He owns a smartphone.

RS: Is a high ranked manager in the city IT department. He owns a smartphone.

RNS: Is a former senior manager in the IT department. He is of "Indian" origins and owns a smartphone.

RPPU: Is a coloured mature man working for the public participation unit (PPU) of the city of Cape Town. He owns a smartphone.

SITA: Is a coloured man and senior IT manager at SITA. He owns a smartphone

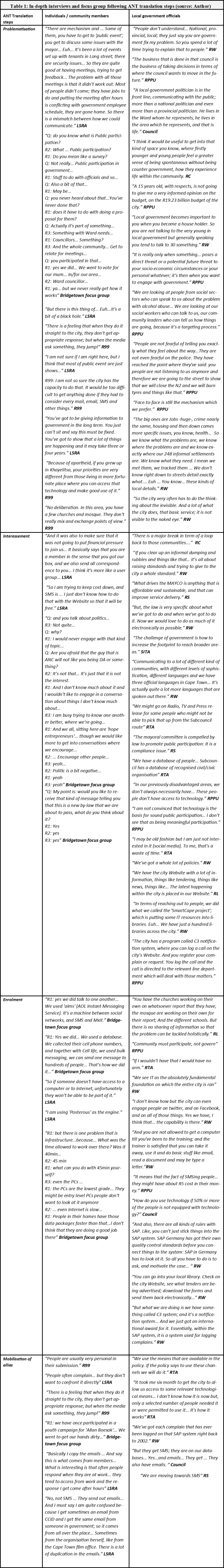

The table (see Table 1) that follows presents a selection of commentary from interviewees and focus group participants. The data is presented following ANT translation steps.

The next section presents and discusses the translation of e-participation in the city of Cape Town step by step.

8. TRANSLATION OF E-PARTICIPATION IN CAPE TOWN

The findings are presented in this section following ANT translation steps with reference to the literature and document review, focus group and in-depth interviews, and conclusions will be derived from them.

E-participation in the City of Cape Town can be understood as the result of the country's strategic commitments and initiatives to achieve that just, peaceful and prosperous South Africa (Republic of South Africa, 1996). These strategies and plans can be read in the legal environment and institutional arrangement at all levels of government. The section continues with a depiction of some relevant legal and institutional elements at national, provincial and local levels, with a hint about community members from the city subcouncils which were the focus of the study; and by positioning the mobile channel within the lines of communication between the stakeholders.

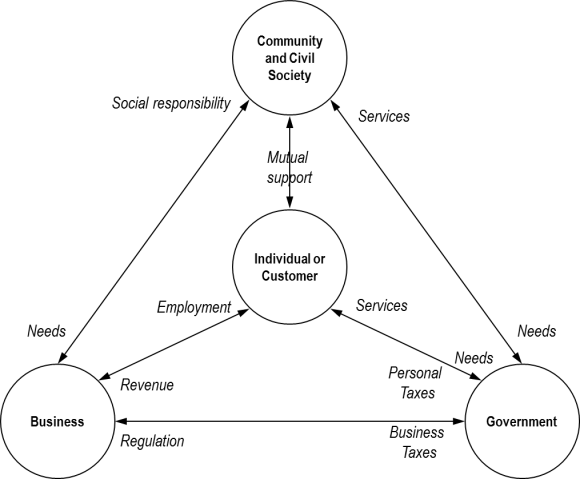

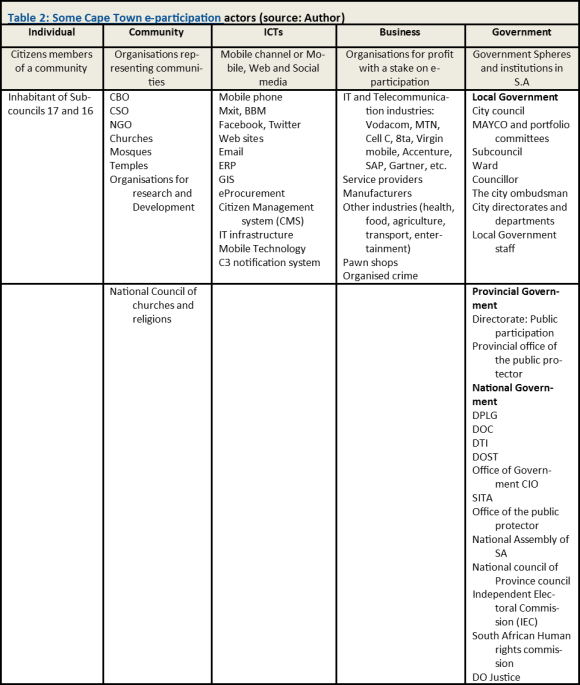

8.1 Actor, Network, Punctuation Rules, OPP

Taylor (2004:117), Taylor & Bytheway (2006) and Taylor et al. (2010) identified a set of 4 interacting conceptual stakeholders for community informatics: Individual, Businesses, Community, and Government (see Figure 1). The paper considers them as e-participation actors, and adds a fifth actor who can be situated within the lines of communication between the stakeholders: ICT constituting the mobile channel or Mobile, web and Social media in the case of this study (see Table 2). That consideration is made to comply with the ANT requirement of generalized symmetry.

Furthermore that grouping simplifies the complex of relationships between members of each group of actors, and provides a sense of "punctuation" as understood with ANT (see Figure 1). However, the study focuses on the interaction between individuals in communities and the local government. Interactions with other stakeholders mentioned here were included where appropriate to support arguments.

8.2 Problematisation of E-Participation in Cape Town

At this stage of the translation, the focus is on the identification of the problem and the development of solutions and strategies to achieve objectives.

The problem to be solved is that the apparent weakness of traditional public participation channels may lead citizens to violent demonstrations as they seem to perceive these to be the best recourse to being heard in government. One solution would be to improve the process using mobile, web and social media channel in Cape Town. That involves providing the government with the ICT capabilities and getting the other stakeholders to buy into the proposed solution.

A priori, the government of South Africa positioned itself as the OPP, by setting up the rules as provided by the legal environment described earlier and arranging institutions to make e-participation happen (see section 3.3). Documents suggested and it was confirmed by interviewees that the government of the city of Cape Town inherited that position, and enacted, invested in ICT and developed systems. The city seeks legitimacy and high standards of processes in service delivery. This is suggested by reported investments and initiatives and words from officials (see sections 2 and 6). This implies that there is a vision that includes all individuals in decision making, and a belief in greater accountability, effectiveness and coherence in delivering services.

However, despite regulatory provision to use all means affordable and useful for inclusive decision making, there is the interpretation that redefines the role of the community member as a passive observer whose role is "to participate, not govern"; summon to be heard at a chosen time. That seems to have removed the capacity for real inclusion from local government preferred face-to-face interaction with the public.

Additionally, the legal environment of public participation, the structure, the organisation and the functioning of government were seen to be preventing the necessary transformation required to accommodate the emergence of e-participation: an interviewee qualified the government to have a "heavy administration".

Clearly, at this level, the stage was set but a lot still remains to be considered including re examining the attitude of officials towards community members, providing community members with information which will benefit from their genuine hope that the government can improve, and which will also benefit from officials' acknowledgement of their work being misunderstood. The quality of the next step, Interessement, should be helpful here.

8.3 Interessement

This moment of translation recalls all the efforts by the government to promote its strategy and to work towards its implementation; the legal environment and existing investment in ICT do not suffice to achieve e-participation.

One of the most important issues of eGovernment implementation is at stake, namely: government transformation that will properly accommodate new technologies and achieve the organisational and procedural changes that are necessary for success.

Interviewees pointed to difficulties experienced by some decision makers, as well as members of the public and businesses trying to get in contact with government using the new technology.

Another issue inherited from the Apartheid era is the lack of e-skills, with the majority of the population being decades behind in terms of the skills commonly found in developed countries and amongst the advantaged portion of the population.

Another issue impeding the progress of adoption of e-participation by the public is their perception of the government which is seen as not listening and non-responsive, "a Black hole". This adds to the public perception of the government as being almost totally ICT illiterate, while the public themselves have the skills to interact with one another using web capabilities on a PC or on a mobile phone, even on the move; things that officials are not yet well acquainted with. On the other end, officials do not trust individual accounts which are considered to be inconsistent and too emotional to provide any basis for an objective input in decision making.

In addition, community members showed ignorance of regulations and ignorance of government structures, organisation and functioning. This might result in misinterpretation of government actions and initiatives. Thus, discomfort in using and poor knowledge of government initiatives including C3 system and the city website will, in the future, prevent individuals from accessing these available channels and content.

The mobile channel, despite a strong backend system, is weak. Respondents said that they have never received an 'SMS' from a government department or from a city official; furthermore, that channel is only considered for 'SMS' because it is what officials so far deem useful and understandable. But 'SMS' is still too expensive for the average mobile user to be considered as an effective way of interacting with government. At the same time, Mobile web applications like Mxit or Twitter are gaining momentum with the public; but these applications, Internet service providers, and other mobile operators are private businesses looking for profit and only avail their products for a price. Local government does not understand or is reluctant to go that route, according to officials who still find social media more ludicrous than useful.

Furthermore, even though the national framework on Public Participation provides for councillors to use any means at their disposal for public engagement, the city policy is rather vague when it comes to technology such as 'cell phones, website, Internet and email to community organisation'. There is no word on social media, mobile web and other applications that the people often use. In Cape Town it's still all about what the respondent "Council" called 'foot work'. There is little prospect of achieving the benefits that are seen elsewhere, for example in the Demo-Net project, and this examination of Interessement reveals barriers to successful transformation that are too significant for e-participation to be a reality in the Cape Town context.

8.4 Enrolment

National Government set roles for all stakeholders of e-participation within its strategy documents, policies and laws.

Local government as the service delivery arm should foster public participation, reaching out and opening up to all the other stakeholders or actors of the network, via any channel available. For many reasons evident at the interessement phase, there is still a long way to go.

Individuals are expected to participate by submitting their views to government whether via an organisation or on their own capacity, by any means, electronic or not, especially for those means (public meetings, toll numbers, councillors, etc.) availed by local government. Poor perception of government, high cost of communication, and unclear mobile communication channels are some elements not favouring the role of the individual.

Communities which are visible through representative organisations are expected to make their needs and opinions known using all legal means over and above those available to a single individual. Despite a lot of work on the ground to identify the needs, the little consideration that is given to community organisations hampers their significance.

Businesses are expected to accompany the whole process and to allow underprivileged communities some opportunities to participate. Despite being ready to work with local government, businesses perceive that they are still not given the opportunity to make a viable business out of carrying the community's voice.

Mobile, web and social media should help to improve the collection of needs and opinions, by allowing to realise community deliberation, by speeding up the processing of information, by recording more information and availing a direct link between a decision maker and each member of the community. It has already gained an important place in individual, businesses, communities and government life, but it is not yet well adopted to render exchanges possible between all actors. These advances include:

- The availability of cellular networks over the whole city providing access to Internet, a guarantee for reaching Web applications and social media from a mobile phone.

- The increasing and impressive social media membership and activities on Mxit, Facebook, and BBM, individuals and organisations, making enormous amount of information available about their preferences and their needs.

- Initiatives including Smartcape, SAP ERP system, the use of mobile telephony, SMS messaging, GIS system, C3 notification system, the validation of councillors and officials using technology, a portal rich in information and a presence on social media indicate a certain openness to change and technology innovation.

- The belief that mobile devices can be useful for work whereas Web and social media are just for fun prevents officials from reaching out to individuals online where they are easily accessible.

These elements assert of a problematic Enrolment as a result of a questionable Interessement, and suggest an even more problematic mobilisation of all these poorly aligned allies.

8.5 Mobilisation of Allies

At this stage of translation, a collective effort is needed to take the use of mobile, web and social media for public participation to a broader public and gain their acceptance as contributing to solving poor articulation of needs. Interviews did not bring important evidence of councillors embracing mobile, web and social media, and making of it an essential tool of public engagement but rather indicated in their attitudes as to how unready they are to take up e-participation. Similarly, community members also arrive at this stage with an unclear attitude towards e-participation and therefore are not ready to take up the use of mobile, web and social media for public participation.

Hence, despite all the good deeds undertaken and endeavours performed, for many reasons at the interessement and enrolment steps, the result is very small in terms of capability and will to mobilise more allies: a stable nucleus has not yet formed that will mobilise new allies and grow e-participation network well enough for the city to benefit.

9. CONCLUSIONS

As a developing country aiming to achieve MDGs, South Africa has ostensibly chosen the ICT route to support its strategy. A mandate was given to local government as the service delivery arm of the government. Within Cape Town, actions have been taken but results have been disappointing: community unrest prevails and seems to be worsening.

The application of ANT using data gathered from literature and document review, in-depth interviews and focus group in Cape Town, reveals dynamics favouring and impeding the achievement of e-participation in the city. In ANT terms, the hopes and expectations of individual Actors are dashed by the limited extent and quality of the network that presently supports them.

The use of mobile, web and social media technologies is widely expected to be an important feature of improving public participation in government in the city of Cape Town, but it is found that the necessary transformation that would enable it is far from complete.

Problematisation was achieved and provided a momentum for an uptake, but interessement is slowing the whole process down with various issues of transformation; Enrolment hampered by inadequate interessement does not see all actors acting as their role would like them to: and at the end - because of all the issues mentioned earlier - e-participation is still at its beginnings in Cape Town.

The study presented here is limited in scope (resource, time and space) and uses ANT which is still a contentious methodology.

Further research should broaden the scope of the study to the whole city and use complementary methods and adjustments to ANT for more reliability. Research should look at ways to get local government to connect with stakeholders using mobile, web and social media by generating models and deriving strategies and action plans that foster the inclusion of all in e-participation in policy making.