Optimisation of Livestock Identification and Trace-back System LITS Database to Meet Local Needs: Case Study of Botswana

Lecturer, Information Systems, Department of Library and Information Studies, University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana. Email: mooketsibe@mopipi.ub.bw

1. INTRODUCTION

The use of ICTs as tools for effective governance and service delivery has long been recognised (Thompson & Walsham, 2010). Furthermore, investments in Information and Communication Technology (ICT) are driven by expectations of increased usage of technology to run core business activities (Bates, 2000). ICT developments are normally initiated to serve specific social, cultural or economic goals of a country. Depending on the intended purpose of the ICT innovation being introduced, the extent of stakeholder consultation done and the amount of effort made to provide for other local needs, the use of such technology may yield unsatisfactory results or benefits for stakeholders.

Due to the large trade preference of 50% to 93% it gets compared to the 40% it gets in Southern African Customs Union, Botswana prefers to sell its beef to the European Union (EU) (Botswana Export Development and Investment Authority, 2008). After the outbreak of Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) or Mad Cow Disease in late 1997 and early 1998, the EU put in place a food law that stipulated that all food products consumed in the EU be traceable. The law further outlined expectations on the traceability of food products, withdrawal of dangerous food products from the market, operator responsibilities and requirements applicable to imports and export. The Livestock Identification and Trace-back System (LITS) was undertaken by the Botswana Government to meet this traceability requirement at a cost of 126 million euro (Stevens & Kennan, 2005). LITS is a system that uses radio frequency identification (RFID) technology. This technology is used to capture data on individual cattle and their owners, and transmits it directly to a central database (Burger, 2004).

This research seeks to explore the extent to which the Livestock Identification and Trace-back System is used to support farmers in cattle management and to establish if it could be used for tracing stray cattle. This is in line with the government vision that by 2016, the people of Botswana will be able to apply the potential of computer equipment in many aspects of their lives (Botswana Government, 1997).

As highlighted by the UN Report on Least Developed Countries, technology has to be adapted to suit different context and uses (UN Report of Least Developed Countries, 2007). This adaptation of technology to suit different context and uses is known as Community Informatics. Community Informatics refers to the modification and adaptation of ICT to help in the attainment of community objectives and needs (Gurstein, 2003). In this instance, the community need is to enhance the chances of farmers getting information about their stray cattle. This is based on the premise that "communities have characteristics, requirements and opportunities that require different strategies for ICT intervention and development from the widely accepted implied models of individual or in home computer/Internet access and use" (Gurstein,2003). This implies that there is need to explore the options and viability of adapting and taking advantage of readily available technologies for the enhancement of service delivery.

2. ICT USE IN CATTLE MANAGEMENT (TRACKING AND TRACE BACK SYSTEMS)

2.1 Traceability

The European Union defines traceability as "the ability to trace and follow a food, feed, food-producing animal or substance intended to be incorporated into a food or feed, through all stages of production, processing and distribution" (Cooke & Hawkins, 2005). The New Zealand Working Group (2004) defines traceability as "the ability to track and/or trace product flows in both fresh production and (in) an industrial distribution chain. Traceability implies that products are uniquely identifiable, that at critical points in the production and distribution processes, the identity of product flows are logged, and the information is systematically collected, processed and stored". There are two types of tracing activities, namely, upstream tracing and downstream tracing. Upstream tracing refers to the reconstruction of the history of a product from its current place to its place of origin. This is vital in that it allows one to rightly identify where the product originally came from and if need be delimit possible places or stages during which identified defects could have occurred. Downstream tracing refers to tracing the events or modifications made on a product after its raw material state. 'Raw material' is taken as starting point and the products that contain that raw material are identified (New Zealand Working Group, 2004).

Specifically concerning red meat, EU regulation (EC) 1760/2000 outlines the requirements concerning identification, registration and labelling of cattle and beef products. The core objectives of the regulation are to:

- "establish an efficient system of identification and registration of cattle at the production stage.

- define a common European labelling scheme for the beef sector based on objective criteria at the marketing stage of the food chain" (Cooke & Hawkins, 2005).

2.2 Botswana Livestock Identification and Trace-back System

The Livestock Identification and Trace-back System is used to capture data on individual cattle and their owners, and transmits it directly to a central database (Burger, 2004). It is comprised of two subsystems namely the Database Management Query and Reporting Subsystem and the Livestock Identification and Data Acquisition subsystem. The Database Management Query and Reporting Subsystem (DMQR) consists of the National database, DMQR Application, Basic WAN Interface, MoA and Query and Reports Interface and the Disaster Recovery plan whilst the Livestock Identification and Data Acquisition subsystem consists of the bolus. The bolus, which is inserted in the cow, has a unique ID number which identifies the cow and its number is read by a reader which is a hand held device and can be used in kraals or crushes. The information from the bolus is then linked with the following information; Cattle Owner's name, Cattle Owner Omang (Personal Identity number), brand, brand position on the cattle, gender of the cattle owner and the animals' colour, location and date. This information is then uploaded to the agricultural officer's personal computer in the District Office through a docking station which operates through the Government Data Network. The docking station then uploads the data to the Central database in Gaborone. The Central database comprises the primary server at the MoA and duplicate cluster server housed at the Department of Information Technology (Department of Animal Health and Production, 2007).

As at June 2006, a total of 2,243,007 out of 3 million cattle had been inserted with the bolus throughout the country. Once all animals are fitted with the bolus, the system will be the "world's largest livestock tracking, monitoring and management system using RFID technology" (Burges, 2000).When animals are slaughtered, the bolus is retrieved for recycling, which keeps the costs low. As at March 2005, a total of 223,120 boluses had been recycled (Department of Animal Health and Production, 2007).

The system objectives are, over and above meeting the EU requirements to "consolidate existing databases within the Department of Animal Health and Production namely the National Disease Surveillance database, Brands database, BMC database, Livestock Movement Permits database, Analogue Ownership Records Analogue Health and Production Records" (Burges,2004). Currently, it is possible to perform the following tasks online; issue movement permits, change ownership documents, log vaccinations, initiate disease reports conduct the census of cattle, issue brands certificates and duplicates, and issue herd cards (Department of Animal Health and Production, 2007).

There are plans for the system to be integrated with existing IT infrastructures within the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) and Government Computer Bureau to allow online client queries for departments such as: National Identity for Ownership Identification, Registrar of Birth and Death for certification of ownership of brands and livestock, the Police for confirming ownership of brands and livestock and the Ministry of Finance to establish revenue from livestock for tax purposes.

3. METHODOLOGY

The target population of this study was cattle owners, the Police, and MoA staff, District Council officers in the South East, Kgatleng and Central districts of Botswana. The Police were chosen as respondents because they receive reports on loss of cattle or the presence of stray cattle; MoA staff insert the bolus and scan cattle as and when required, and the District Council staff are in charge of stray cattle. A decision was made that all prospective interviewee cattle farmers within the specified distance parameters had the same chance of being included in the study (Busha & Harter, 1980). Different questionnaires were designed and administered for the various respondents and the responses from the different categories of respondents were triangulated to check the reliability of the answers given by one category of respondents against the other (Borg & Gall, 1989).

Random sampling was chosen due to the fact that it was difficult to identify an appropriate sampling frame. For the South East the selected main villages were Tlokweng and Ramotswa, for Kgatleng the selected urban villages were Mochudi and Oodi, whilst in the Central district the selected urban villages were Palapye and Tutume.

Given the nature of this study, it was decided that data would be collected through the use of questionnaires which were to be administered during face to face interviews. This is because the population under study is diverse, some of the farmers are educated people and some are illiterate. Thus the likelihood of the questions being difficult or in a language that the respondents do not understand could not be ruled out. The researcher personally distributed and collected the questionnaires. Respondents were given the questionnaires to fill out and in cases where the respondents could not read or write, the researcher conducted interviews them and filled out the questionnaires on their behalf. The questionnaires were directed to household heads in the cattle posts or whoever was in charge of looking after the cattle. For the Police, MoA officers, and District Council staff the questionnaires was administered to the head of duty station.

Sixty cattle posts were identified and responses were obtained from forty-four of the cattle posts giving a seventy percent response rate. Of the fort-four farmers who responded four were commercial farmers. Thus commercial farmers comprised nine percent of the respondents. Of the six head of stations of Police, six MoA officers, six District Council staff, responses were obtained from four of each giving a total of twelve responses translating into a 67% response rate.

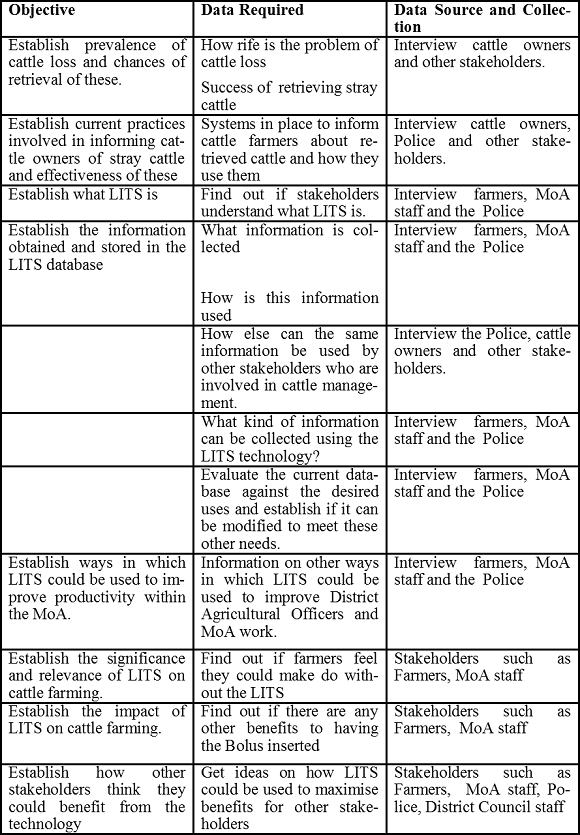

3.1 Data Requirements

Below is a summary table of objectives of the research, data requirements and sources that were used to guide the framework of the study.

4. FINDINGS

4.1 Prevalence of Stray Cattle and Related Support Services

Stray cattle that are not found translate to loss of revenue. Whilst cattle loss can be attributed to other factors such as theft, drought and other issues and as such it is inevitable, failure of cattle owners to retrieve their cattle when they have been collected by government officials as strays is regrettable and avoidable. In Botswana, these animals are called matimela which can be loosely translated to mean lost animals.

Of the interviewed farmers, 45% said they had not lost any cattle in the past year while 55% stated that they had lost some of their cattle. Predominantly, the 45% that had not lost any cattle were commercial farmers. While it cannot be concluded with certainty that these lost cattle were collected as matimela, the chance of this having happened cannot be ruled out. This is because whenever a cattle farmer has a cow that does not belong to him amongst his cattle; he is expected by law to report its presence to either the chief, MoA officers or District Council officers in charge of stray cattle. This practice was also confirmed by those in charge of stray cattle as when asked how the office responsible for stray cattle gets information on stray cattle, all of them said that villagers report to them, the Chief or MoA officers. The same response was obtained from the MoA officers.

4.2 Retrieval of Stray Cattle

With regard to retrieval of stray cattle it seems that the chances of recovering missing cattle are really poor as only 18% of the cattle farmers who had lost some of their cattle had recovered some of their animals. This conflicts with what the District Council staff in charge of matimela says as they stated that 50% of the matimela they had in the government kraals were retrieved by their owners.

4.3 Informing Cattle Farmers about Stray Cattle

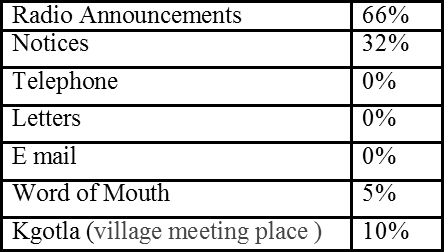

The Matimela Act states that cattle owners should be informed about their stray cattle within fourteen days of the matimela being collected (Matimela Act, 1969). Of the farmers who were interviewed, 66% reported that they were informed of their stray cattle over the radio whilst 34 % said they were informed through notices.

4.4 Radio Listenership to Matimela Program

As a way of publicising and improving retrieval of lost cattle, the national radio station has a program where a list of lost cattle held in government matimela kraals is read out. This study established that 57% of the interviewed farmers said they listened to the program every time it was on; though this depended on them having batteries to run their radios. It should be pointed out that the program runs once weekly and does not cover all the government kraals during the session but rather each session focuses on a specific kraal.

Source: Survey Data

Despite councils being expected by law to widely publicise the information on retrieved stray cattle so as to ensure that the information reaches as many people as possible, this study established that only seven percent of the respondents stated that they had seen the notices on matimela (Stray cattle) in places like clinics, councils. There are places like the cattle crushes and boreholes' where almost all farmers go daily to water their cattle where these notices could be put up. The telephone and email were not used at all. The email could be a viable way of informing the public about stray cattle as the Government Data Network (GDN) provides service to all government offices and covers close to 100 villages and towns and connects over 7,000 civil servants (Sebusang and Masupe, Online).

4.5 Information Included in the Matimela List

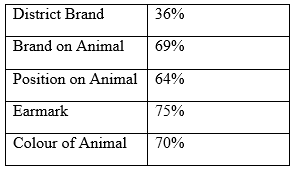

This study also considered the issue of information included in the matimela list. Ideally, information included on the list is intended to make it easier for people to find their lost cattle. However, the list as is, means only those close to the cow owners can inform them, but if names were included it would be better. These names could be obtained from the LITS database; this is how cattle farmers responded;

Source: Survey Data

Source: Survey Data

4.6 Cattle Farmers' Access to Forms Online

When asked if it is possible to access forms relating to cattle management, like cattle movement forms, online, all the cattle farmers who responded stated that it was not possible. This conflicts with the Department of Animal Health and Production's claim that it is possible to issue movement permits, change ownership documents, log vaccinations, initiate disease reports, conduct the census of cattle, issue brands certificates and duplicates and issue herd cards (Department of Animal Health and Production, 2007). All the MoA staff who were asked the same question said it was possible. One can only conclude that there are functions on the MoA Intranet that are not available to the general public. With respect to the question as to whether or not they would benefit from having access to an online system, 77% of the cattle farmers said that they would benefit from an online system. The benefits they cited are manifold, from reduced travelling expenses to urban villages to get the forms every time they need them, to assurance that they will have the forms as and when they are needed.

4.7 Challenges that an Online System Can Pose

The cattle farmers interviewed acknowledged that there were numerous challenges that they and the government have to overcome before they could be provided with or even benefit from online services. Whilst 6% of the cattle farmers felt that they could use wireless access to the Internet to access online services, 70% of the cattle farmers stated that the main impediment was lack of computers and electricity. The study established that 84% had no access to computers and the Internet. To deal with this, cattle farmers proposed that they could form syndicates and buy computers, if the government provided their settlements with electricity. In addition, whilst some of the cattle farmers accepted that they are not computer literate, they felt that they could be trained to use computers. Forming syndicates to achieve a common goal is something that has been happening in the cattle farming industry in Botswana for a long time, for example, cattle farmers group themselves to dig boreholes to share the costs of drilling, thus ensuring that they can provide water for their cattle throughout the year. It therefore should be possible for the farmers to take such initiatives a step further to enhance their cattle management practices.

4.8 Use of Cell Phone in Cattle Farming

Respondents were asked how they stayed in touch with those who helped look after their cattle if they did not live with them. This study established that 72% of the interviewed cattle farmers have cell phones and that cell phone signals were available in 97% of the cattle posts.

4.9 Cattle Farmers' Knowledge about LITS

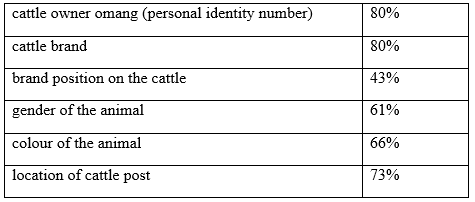

When asked what the identity number in the bolus identifies, that is, whether it identifies the cow or the cow owner, 91% of the respondents said it identifies the cow owner, which was not correct as the bolus has a unique ID number which identifies the cow (Department of Animal Health and Production, 2007). In addition when asked what the information from the bolus is linked to, this is how the cattle farmers responded which indicates that the farmers do have a grasp of what information is stored on the LITS database.

When asked what other information they thought could be collected as part of the LITS database, the cattle farmers felt that their cell phone numbers, names of next of kin and their village residential addresses could be collected and used to enhance contact between the MoA officers and themselves.

4.10 Reasons Why Cattle are Fitted with the LITS

Of the interviewed cattle farmers, 80% had fitted all their cattle with bolus whilst twenty percent had not. The majority of those who had fitted all their cattle with bolus said that they had done so to help them in case their cattle are stolen. Most of these respondents also indicated that the government expects them to fit all their cattle with the bolus. This correlates with the findings that both the Police and traditional leaders use the bolus and the LITS database as and when there is need for verification of ownership, either during a dispute, sale or exchange. 61% of the cattle farmers also stated that they fitted their cattle with the bolus to be able to sell them. It should be noted that no one is allowed to sell his or her cattle if the cattle do not have a bolus, as verification of ownership is done using the data in the bolus and the LITS database before any sale or exchange takes place. Of the 20% who had not fitted all their cattle with a bolus, some had not done so because the MoA officers were not available to do so, some because they had been told there was no bolus available, and some because at the time when cattle were being fitted with the bolus, their cattle were not readily available. The other reason given was that, at the time when the bolus was fitted, some of the animals were still small as the bolus is only fitted in cattle that have teeth.

The majority (86%) of the cattle farmers interviewed indicated that the Police and the Dikgosi (traditional leaders) use the database for verification of ownership in dealing with cases of stolen cattle and disputes over ownership of cattle. This probably explains why 84% of the farmers interviewed had fitted their cattle with a bolus. Despite the reliance stakeholders have on the bolus for verification of ownership, 75% of the Police officers who responded raised a concern that, at times when cattle are scanned, the bolus just reflects numbers and does not give any other data.

4.11 Access to the LITS Database by Other Stakeholders

The District Council officers in charge of stray cattle expressed concern about lack of access to the database. They stated that they needed to be allowed access to the LITS database to enable them to retrieve relevant data and use such to contact farmers as needed. The same concern was raised by the Police officers who responded to the questionnaire. There is need to resolve the issue of access to enable other stakeholders to improve the services they provide.

4.12 Recycling of Bolus Retrieved From Dead Cattle

When farmers were asked what they did with the bolus they retrieved from their dead cattle, 23% said they did not know what to do with the bolus when they retrieved it, 5 percent said they took it to the traditional leader, and nine percent reported that they threw it away. When asked what mechanisms were in place to ensure that farmers returned the bolus after retrieval from their dead cattle, 100% of the MoA staff who responded stated that there were no systems in place to ensure this.

4.13 Support from Veterinary Officers

It emerged that 86% of cattle farmers were concerned that they got no support from the MoA officers to help them retrieve their stray cattle. They felt that the officers should collect data on matimela as they moved around the districts as farmers were always likely to inform them that they had stray cattle in their kraals and that they should use the LITS database to get additional data on who owned the stray cattle by scanning them. The current practice is that even if the farmers report the stray animals to the MoA officers, the officers do not do anything else except inform those in charge of collecting the stray animals.

5. DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

The findings of this study point to the fact that chances of recovering strays are low especially amongst traditional farmers. There is need to ensure that as much as possible is done to assist the cattle farmers to retrieve their cattle. The following should be considered to reduce loss of cattle and help farmers retrieve their lost cattle in a cost-effective manner.

5.1 Management of Lost and Found Cattle

More data should be included in the LITS database that will enable cattle owners to be traced easily when there is a need. Such data would include, for example, telephone numbers and contact details of the next of kin of the farmer so that, where it is difficult to reach the farmer, the next of kin can be contacted to help. There should be a database of farmers in each cattle post or area capturing necessary data including name of cattle post, name, identity card number, contact details and physical address of each farmer, cattle brand of farmer, etc to facilitate communication with farmers on matters pertaining to care and loss of cattle.

When the District Council staff are in a particular area or cattle post gathering stray cattle, representatives of the area should accompany them to ensure that cattle bearing brand numbers captured in the database for the area are not taken to the government kraals. Once the animals have been gathered, the Veterinary Officer for the area should scan them to retrieve data from the bolus to be used together with the database for the area, to ensure that cattle belonging to farmers in that particular area or cattle post are not taken away.

Usage of the LITS, bolus databases would help in this aspect. The added bonus would be that costs of looking for lost cattle would be reduced especially since it would not be necessary for the District Council to collect all the lost and found cattle from the cattle posts and take them to the government kraals which are district based and far from the cattle posts. The farmers would not travel long distances looking for their lost cattle as much as they would otherwise, since they would be informed of where to collect them. It should be noted that the majority of the traditional farmers do not have vehicles and as such they incur heavy expenses in collecting their lost and found cattle from the government kraals. The District Council should only deal with cattle without brands, bolus or earmark.

5.2 Provision of Support Services

The MoA, especially the Department of Animal Health and Production, should set up an interactive website to publicise the services it provides and allow for contact with its clients. Given the low population of Botswana and the communal lifestyle, notices and announcements, which should include names of owners of the lost and found cattle, should be put up at the Kgotla, Veterinary Offices, shops, clinics, hospitals, schools and other prominent places to enhance accessibility of information on lost and found livestock. Such notices should also be distributed to other regions so that if lost cattle from other areas or regions are found in a particular area; the owners can get information about where they have been found. A government website specially designed for this purpose could also be set up. There is need to widen the range of media used to inform cattle owners of stray cattle. The Veterinary Officers should be available whenever lost cattle are gathered or reported to retrieve data from the bolus and generate lists to be used to inform members of the community about the lost and found livestock and identify the owners.

5.3 Access to the LITS Database

It is commendable that the database is being used by the Police and traditional leaders but there is need to allow them full access to the database to enable them to work with it independently. The access can be restricted to read only if there are concerns of data integrity or privacy. It is also important that all stakeholders get together to discuss ways in which the data base could be used to help them improve service delivery in their respective departments.

5.4 Handling of Bolus Retrieved from Dead or Slaughtered Cattle and Monitoring

Farmers are expected to return those bolus retrieved from dead or slaughtered animals to the Veterinary Office to update the LITS database and for recycling. The study has revealed that some farmers do not return the bolus and do not understand the importance of doing so. The resultant situation is that the LITS database does not reflect the actual population of cattle in the country and this may impact negatively on management matters associated with provision of resources, animal health services and general support services to farmers. Furthermore, the situation militates against recycling efforts made towards achieving cost-effectiveness in the maintenance of LITS. There is therefore need to establish and implement monitoring mechanisms to ensure that farmers return the bolus for recycling and updating of the LITS database. The Veterinary Officers should work with the local authorities to educate farmers about the importance of returning the bolus and regularly check with the farmers concerning the number of their cattle. Each time they are out inserting bolus or providing other services, they should collect data from each farmer on cattle available and check if they have bolus from dead or slaughtered cattle.

6. LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

The cattle farming industry in Botswana is complex. In some instances the cattle owners stay in villages or spend the week days in towns and only go to the cattle post at month end, whilst in some instances they stay in the cattle posts permanently. A decision was made, therefore, to go to the cattle posts and interview those farmers found in the cattle posts. This inevitably means that the possibility of having omitted those who go to the cattle fields only at month end is high. This, however, does not have any negative impact as their cattle herders, in this instance, were involved since the questionnaire were directed to the head of households or whoever was in charge of looking after the cattle. Furthermore, it was not possible to obtain a sampling frame as lists that could have been used were not available since registration for births, deaths, elections or any services are done in the home villages (Schapera 1996).

7. CONCLUSION

Conclusions drawn from the study provide issues to be addressed regarding optimisation of the LITS database to enhance the value derived from the system. This study has highlighted that there is potential to use the ICT's that are in the cattle industry for other purposes. These will make the system benefits more than they are currently as it will be used to solve everyday problems such as stray cattle. This will be in line with the concept of community informatics that whatever technology is introduced, it should be adapted to betterment of the community.