Professor, Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia.

When I began to write this paper, the first question I asked myself was, in what sense could an examination of trajectories and modes of use of the mobile telephone, chat, the social webs in Internet and electronic mail among urban young people, be considered features of innovation and resourcefulness? It is clear that the form of this innovation comes neither from the engineering, scientific and technical communities who create the new technological device, nor from the groupings and social communities which unfold and devise unexpected and ingenious modes of inserting the machines in the course of their lives. When I reviewed my notes I understood that the innovation that I wanted to emphasize was more like the anonymous, non-premeditated, emergent and penetrating transformations which unexpectedly change people's course in a silent way. Let's imagine for a moment how the invention of planting rice in terraces occurred; or respiration techniques and their effect on people's emotional, corporal and cognitive states; or the invention of popular flavors and tricks of the kitchen; or ways of placing and distributing food on the table. These are examples, perhaps a little bizarre, of a penetrating, emergent and silent invention, without a defined moment of genesis, without visibly responsible innovator and without the possibility of assigning an individualized authorship. An example which is closer to the topic that we are dealing with is illustrated by Rheingold (2004) when he refers to the introduction of emoticons into the technologies of exchange and the sending of textual messages.

It was precisely Rheingold (2004) who has emphasized the coordinated, intelligent and massive character which seems to emerge from wireless webs and mobile communication settings, by allowing "original activities to be carried out and in situations where collective action had not been possible until now" (Rheingold, 2004:23) The purpose of the doctoral thesis from which this paper is derived, consists precisely in tracing this collective intelligence (Lévy, 2004) in relationship to the genesis of links mediated by people's new technological repertoires. This paper suggests that people are generating at least eight patterns or configurations of the new technological repertoires in order to deepen, evolve, transform and renew their social links. The innovation refers precisely to the invention of these patterns which cannot be attributed to or explained as a pure derivation of the technical structures of the machines.

The research was carried out in Cali (Colombia); it was based on the follow-up to the techno-linking dynamics of a group of young people in Cali over eight months: Lina, Sara, Yulia, Mafito, Miguel, Juan Diego and Nino. Their ages ranged between 17 and 22 years, they are university students or in their last years of high school, and they all maintain a very complex and interesting relationship with the technological tools previously mentioned. In methodological terms, the study used qualitative research strategies (in-depth interviews, ethnographic observations, conversations) and the use of a computer tool, the State Space Grids (Laney et al, 2004) which offers interesting alternatives for processing, analysis and data graphics1 .

The article examines the framework of technological relationships between human and non-human agents. It proposes eight techno-mediation linking systems which can be used for analyzing variations in the techno-linking settings of urban young people and questions some of the frequently simplifying conceptions regarding "the young users of new technologies".

This paper has two critical assumptions. In the first place, this article understands that mobile phone, chat, and email are different and that, a mobile phone integrates increasingly varied functions and applications (chat, email, phone calls, location, social networks). The technological function is what is important, not the artifact. Second, this paper proposes a classification system of relations between young people and new technological repertoire that is not based on previous literature. This classification emerges from the empirical work, categories are "rooted" in the experience, as discussed for example in Grounded Theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). The paper we should note, suggests hypotheses for discussion and presents no definitive conclusions.

The study allowed us to advance our understanding of the new technological repertoires (NTR)2 not as isolated instruments which are added to the social life of the subjects, but rather as technological mediations for the construction of social links, that is, as linking machines. Technology users do not connect with discrete and individualized technologies (mobile telephone, chat, Internet) but rather with authentic technological settings in which both convergent and divergent relationships are generated. We call this conjunction of technologies the ecology of technologies.

The way in which each subject is situated in this techno-linking setting varies in time and changes according to the linking tasks to be carried out. This relationship is altered according to a significant volume of junctures and processes which include the value and cost of use of the machines, their availability, and the manipulation skills, even customs, particular interests, generalization of behavior patterns and models associated with their use. These variations in the behavior of the set of technological mediations result from the way in which the relationships between human and non-human agents (Latour, 1998) start to unfold over time. The density of these relationships is irreplaceably, vigorously and extraordinarily complex. In the study it was possible to observe how the young participants have come to weave very particular stories and relationships with each technological repertoire. For example, Miguel, with his mobile telephone3 , Nino and Yulia with their personal computers 4 , Mafito with his social webs page. The presence of these non-human agents along with those which are constructing a network of human and non-human tasks, links and co-ordinations, configures an authentic, cognitive and affective system of relationships whose scope and complexities are beginning to be recognized (Piscitelli, 2008; Rueda, 2007; Rheingold, 2004; Latour, 1998; Callon, 1998; Levy, 1995; Martin Barbero, 1987; among others).

We found the weight of one technological mediation as compared to the others in the study's individual participants to be overwhelming. It is as if, at times, one linking machine was absorbing the others, sweeping them out of the technological scenario. At other times, there is, to put it metaphorically, a wholesome coexistence among non-human agents, and the subject would appear to concede an important place to all the technological presences in the operation of its links and affective webs.

Within this ecology of technologies, we analyze how many technologies which tend to be central are in each trajectory, what place they occupy in the trajectory and how they relate among each other. There might be one, two, three or four technologies in each trajectory which turn out to be central to the social link transactions. We will address the mono-technological, bi-technological and multi-technological systems.

The following is an analogy which can be useful for us. Let us imagine we have land in which we cultivate different species of plants. That land is the link space. In order to take care of and grow plants, we use different technologies (those technologies are the NTRs). It might occur that we turn to the use of predominantly one technology (in this case we are speaking of a mono-technological system). But then our crop might require two technologies (a bi-technological system). Or perhaps it needs three or more technologies (a multi-technological system). In our study we were interested in determining which is the dominant behavior pattern in relation to the number of technologies (one, two or more technologies) that the subject uses for the construction of their social links. When speaking of a mono-technological system, it does not necessarily indicate that the dominant technology at that moment will be the same that will predominate at another mono-technological moment in the trajectory. The important detail is that the subject tends to repeatedly appeal to only one technology in order to cultivate the entire link space. In this sense, we are referring to a:

By making a detailed follow-up of the participants' trajectories, we were able to see the warp which emerges from the relationship between the subjects and the new technological repertoires and recognize the diverse place that these repertoires are playing in the construction of the participants' social links. The studies concerning the relationship between young people and the NTR, other than analyses of access to the technologies, should deal with the follow-up on the complex relationships which are established between people's lives, their vital experiences and the technologies.

When considering the unfolding of the trajectories in time, the analysis allows a demonstration of how the technologies are articulated within the universe of links which each subject establishes. One might expect that this would entail slightly more stable trajectories, but what we find is constant fluctuations and variations: there are jumps between particular moments and diverse uses of the technologies within the same trajectory. Beginning with what we might call an ecology of linking technologies, has allowed us to define eight technological systems of linking techno-mediation. These systems correspond to types of techno-linking relationships in the social world and challenge the frequently simplified conceptions and classifications of the relationship between young people and technology.

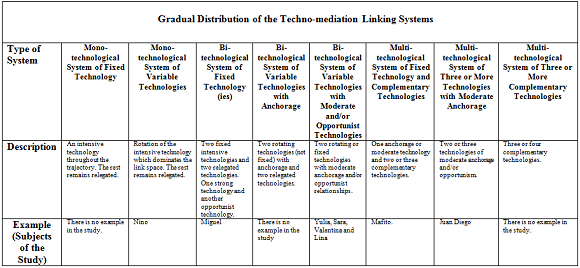

Table 1 presents a summary of eight techno-mediation linking systems concerning the relationships between young people and the new technological repertoires.

Before explaining each of the eight techno-mediation linking systems it is necessary to clarify some concepts:

To explain each of the eight systems synthesized in Table 1:

1. Mono-technological system of fixed technology. This refers to subjects who present a technological system in which only one technology tends to be central throughout the trajectory, while the others tend to remain in marginal or less central positions. We did not find representative subjects of this kind of system in the study.

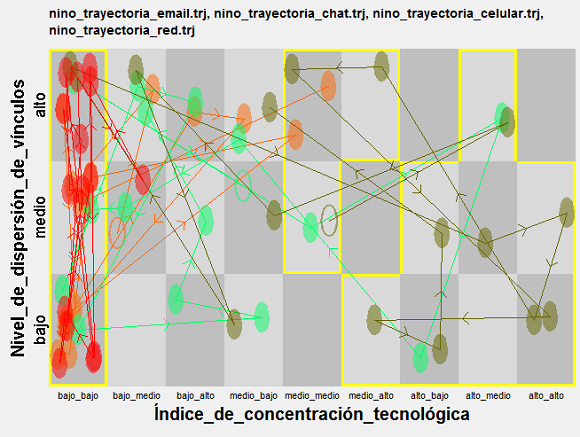

2. Mono-technological System of variable technologies. This refers to a technological system with a central technology in which a kind of rotation of this technology appears throughout the trajectory; the dominant technology changes in time, while the others tend to remain relegated. Nino 6 is the only one of the participants in the study who adjusts to this system. The following figure shows a synthesis of his case:

For Nino, (Image 1) one of the most particular technological distributions can be appreciated. There is a nucleus of extreme relegation at the left of the grid, in which the social webs (red) are concentrated, and a region of extreme dispersion to the right, completely dominated by the mobile telephone (olive green), and with presence of the link space in the three levels. There are three periods in which email (orange) occupies a significant centrality, in a broad link space which makes this dynamic very important. We are facing a vigorously mono-technological system in which there is a dominant technology (the mobile telephone) and yet, chat, in first place and email, in second place, eventually come to dominate the techno-mediation scenario. Let's look at this in more detail in the following Excel graphic:

As pointed out earlier, the web is a completely marginal technology for Nino. Except for period 3, the remaining periods record a low technological concentration index for the web. Thus, for Nino, the web is an attenuated technology. In the first period, with a medium LDI, the mobile telephone and chat are intensive technologies, while email and the web are attenuated technologies. In period 2, the mobile telephone reaches a high-medium level and continues as an intensive technology; chat remains relegated as an attenuated technology, together with email and the web. In period 3, the mobile telephone and chat continue as intensive technologies and share the space of technically mediated links; the web continues to be marginal together with email which remains at a low-low level. In period 4, chat operates as an intensive technology and the mobile telephone behaves - for the first time in the trajectory - as an attenuated technology, the same as email and the web. In period 5, with a narrow LDI, chat becomes a refuge technology, while the mobile telephone appears as a subsidiary technology. The condition of the web and of email continues to be the same as in the previous period. Period 6 for Nino corresponds to the end of the mid-year vacation and generates a significant increase in link space, together with an increase in the TCI of email, which behaves as an intensive technology, together with chat. The mobile telephone becomes an attenuated technology, together with the web.

In periods 7 and 8, the mobile telephone is an intensive technology, while the others remain as attenuated technologies. In period 9, Nino's link space narrows and the mobile telephone maintains its centrality; we then speak of the mobile as a refuge technology (a technology monopolizing a narrow link space), with three attenuated technologies (chat, email and web). In period 10, Nino's link space broadens and even when email gains a little centrality, it continues to be an attenuated technology (the same as chat and the web). The mobile continues as an intensive technology. Period 11 offers us the only example in Nino's trajectory of floating technologies: the mobile telephone, email and chat. In the trajectory which ranges from period 12 to 14, Nino's link space (LDI) narrows significantly and the mobile monopolizes the treatment of this monopolized link space (refuge technology); only in period 14, does chat reach a low-high level, and yet it continues to be an attenuated technology together with email and the web. In period 15, the centrality of the mobile continues, but now with a medium LDI, it operates as an intensive technology. The other three technologies continue as attenuated technologies. In the last period, email reaches its highest level in the entire trajectory (medium-medium level) and turns into intensive technology together with the mobile telephone. This, as with the previous abrupt increases in the TCI of email (periods 6, 10 11) is due to the intensification of Nino's academic commitments in the university.

Nino tends to use one technology (the mobile phone) to monopolize his link space and to sustain a marginal relationship with the technologies for communication and linking machines. However, his dexterity and skills with the NTR are broad, and are related to the computer software manipulation and the creation of databases in order (and to always have available) his personal and academic files and those for his hobbies (mainly music and cooking). This data turns out to be significant to understand the relationship between young people and the new technological repertoires: the complexity in this handling and manipulation of the technologies does not necessarily imply intensive use as linking machines or vice versa.

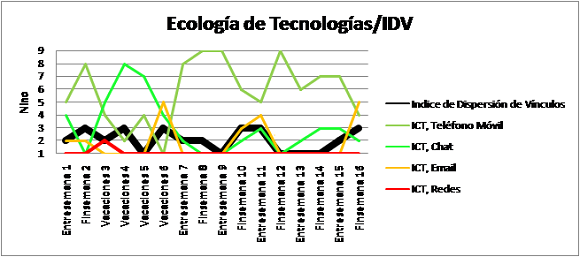

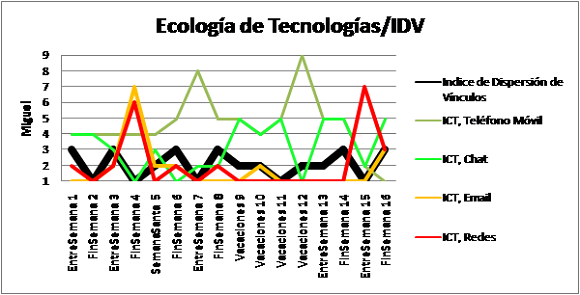

3. Bi-technological System of fixed technology(ies) This concerns a technology system with two central technologies and two relegated technologies. In our study this is the case for Miguel 7 .

In Miguel's case, image 2 shows a landslide in the presence of the mobile telephone at the right of the grid (medium and high ranges). We find another important grouping on the left side (low ranges) with a significant presence of the social web pages (red) and slightly less of email (orange). Chat tends to occupy low and medium zones in the grid. This image points out the centrality of the mobile telephone for Miguel, at the expense of other technologies, with the eventual importance of chat and email to a lesser extent. Let's analyze this in detail:

In Miguel´s case, in period 1, with a high LDI, we see that chat and the mobile operate as intensive technologies (they both occupy a medium-low level), while the web and email are attenuated technologies (they are at low levels of the TCI). In period 2, the link space (LDI) narrows and the mobile telephone and chat become refuge technologies (one or two technologies to cover a small link space), while the web and email continue to be attenuated technologies. In period 3, Miguel's link space broadens and although the TCI of the web and email increase, they continue to be attenuated technologies. The mobile telephone is an intensive technology which has chat as its complement as a subsidiary technology in the process of link space coverage. A transformation occurs in period 4, which is similar to that of period 2: the link space narrows and email and mobile telephone become refuge technologies. This significant increase of the email TCI is due to the fact that in certain periods it becomes a key resource for undertaking schoolwork.. In period 5, the link space grows slightly, the TCI for email falls, the mobile telephone is maintained relatively high and chat increases and the web slightly less. The mobile telephone is the intensive technology and chat, its subsidiary with the web and email in the condition of attenuated technologies. In period 6, the link space broadens significantly (high LDI), chat and email continue to be attenuated technologies, the mobile telephone is the intensive technology and the web becomes a subsidiary technology in the operation of link spaces. It is the only time in which the web reaches relatively high importance in the coverage of link spaces. In period 7 Miguel's intense love crisis causes a significant narrowing in his link space (low LDI) and all of the technologies become attenuated, except for the mobile telephone, which is converted into a refuge technology. As with a rebound effect, in the following period the link space broadened and the mobile telephone becomes an intensive technology with a subsidiary role less than that of chat or the web.

In the span which corresponds to L9 and L10 (school vacations), Miguel's LDI is at a medium level, while chat gains centrality and becomes an intensive technology, together with the mobile telephone which continues to maintain its privileged space within the set of technologies; email and the web remain in marginal places and in this way they continue to be presented as attenuated technologies. In the L11 period, with a low LDI, the situation of email and the web continue to be attenuated technologies while mobile and chat turn into refuge technologies. In L12, school vacations continue and with a medium LDI, the centrality of the mobile is again emphasized in Miguel's trajectory: observe the dramatic fall of the chat LDI in this period and the centrality which the mobile TCI gains (high-high); in this period the mobile continues to be an intensive technology while the other three become attenuated technologies.

In periods 13 and 14, chat again becomes an intensive technology, together with the mobile which does not lose its centrality. The web and email continue as attenuated technologies. In period 15, an important event happens to Miguel: he loses his mobile telephone which extraordinarily triggers off the centrality of the web (it reaches a high-low level) as a technology for the transaction of social links. For the first time in the entire trajectory, the mobile becomes an attenuated technology, together with chat and email, while the web turns into a refuge technology. In period 16, the LDI rises, but the mobile telephone continues to be an attenuated technology while the other three technologies become floating technologies (two or three technologies to transact a broad link space). This fall in the TCI of the mobile in the last periods of Miguel's trajectory and the consequent rise of the TCI in the other technologies (mainly the web), exactly in the same periods, are a new confirmation of the type of centrality relationship which Miguel establishes with the mobile as an important technology for the transaction of his technologically mediated links.

4. Bi-technological system of variable technologies with anchorage. This concerns a technologgy system in which there is the presence of two central technologies which rotate their centrality with each other, while the other two technologies always appear relegated. In the study, none of the participants' trajectories fall within a system of this kind.

5. Bi-technological system of variable technologies with moderate and/or opportunist anchorages. This refers to a technology system with the presence of two central technologies (which can be rotating or fixed) with patterns of moderated and/or opportunist anchorage behaviors. In the study, this is the case for Yulia, Sara, Valentina and Lina. To illustrate, we present the graphics which demonstrate Sara's usage 8.

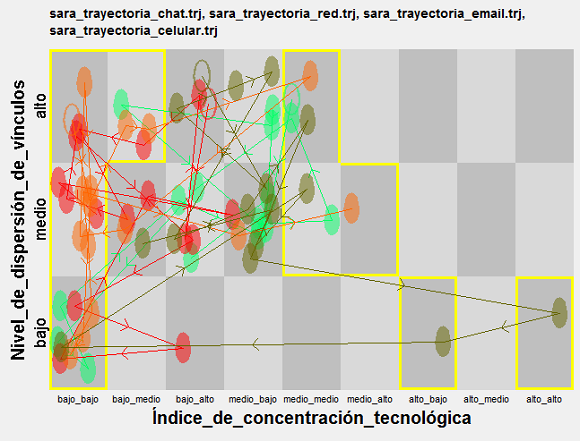

Two large groupings in Sara's distribution of events can be appreciated in image 3. In the medium-low to the medium-medium spectrum of the TCI (in the center and right of the grid), chat and mobile telephone predominate. The second grouping at the low ranges, is devoted to the social web pages and to email, with a lesser presence of chat and the mobile telephone. This is an indication that, although there is a relative tendency toward the dominant techno-linking complex (chat/mobile telephone), this is not guaranteed. Moreover, no technology in the high ranges of the TCI is identified with the broad and medium link spaces, which indicates a moderation in the use of the technological repertoire available for the mediation of links. This is in significant contrast to the mono-technological system as we saw with Miguel (Image 2) or with another multi-technological, as we will see later.

In this graphic we see that in period 1, with a high link space, chat is an intensive technology with two subsidiary technologies: the web and the mobile telephone. Email is an attenuated technology. In period 2, we find a narrow link space, with three residual technologies (chat, mobile telephone and the web) and one attenuated technology, email. In period 3, the link space broadens and we encounter three floating technologies: chat, the web and the mobile telephone. Email, although it rises slightly, continues to be an attenuated technology. In period 4, the LDI remains high. The mobile telephone and chat are intensive technologies, and email and the web, attenuated technologies. In period 5, the LDI remains high and email, which had been marginal, becomes an intensive technology together with the mobile telephone. This sudden intensification of email, is explained by the fact that, in spite of the prolonged break (Easter Week), Sara used her email to transact her responsibilities and university homework. Chat and the web become attenuated technologies. In period 6, the link space (medium LDI) narrows slightly: chat and the mobile telephone become intensive technologies, and attenuate email and the web. In period 7, the LDI continues at a medium level, and chat and the mobile telephone operate as refuge technologies; the network and email become attenuated technologies. In period 8, the LDI increases slightly, but again, both email and the web remain attenuated, and chat and the mobile telephone constitute intensive technologies.

In period 9, school vacations begin and Sara's LDI begins to lower slightly; the mobile continues as an intensive technology, while the other three operate as floating technologies. In the two following periods, Sara's LDI is at its lowest level (they will be the only ones throughout the trajectory that reach this low-low level) and the central place the mobile telephone occupies as a refuge technology (one technology monopolizing a narrow link space) is significant in these two periods; while the other three operate as attenuated technologies. In period 12, the school vacation continues and a very particular situation occurs: the LDI is low and there is no weight of the technologies in link mediation. Sara was at a farm, in a state of complete removal from the four technological repertoires considered in this study. In period 13, the mobile again gains centrality and operates once more as an intensive technology, while the other three are attenuated technologies. In period 14 we find three floating technologies: chat, the mobile telephone and the web. Email continues as an attenuated technology. In period 15, this relationship of three floating technologies and one attenuated continues: email gains centrality (this is the period of midterm exams) and becomes a floating technology together with chat and the mobile telephone, which in spite of everything does not lose its centrality; while the web passes on to operate as an attenuated technology. In the last period, email and chat become intensive technologies; and for the first time in the entire trajectory, the mobile telephone turns into an attenuated technology together with the web.

As can be appreciated, the structure of two groupings which Image 3 offers us is the result derived from this dynamic of the organization of link space centered around two technologies (mobile and chat) which lead a major part of the events toward the medium zone, while the other two (web and email) have the tendency to stay in low zones. For this reason we speak of a bi-technological system with a behavior pattern of moderated anchorage with two technologies which serve to outline and deal with a major part of the technically mediated link space (chat and mobile telephone) but with some presence of the other two technologies.

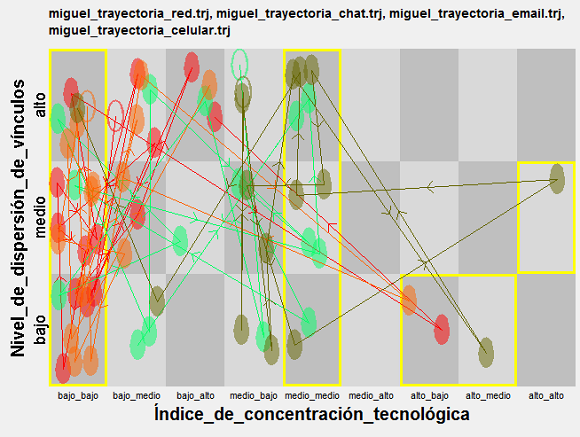

6. Multi-technological system of fixed technology and complementary technologies.

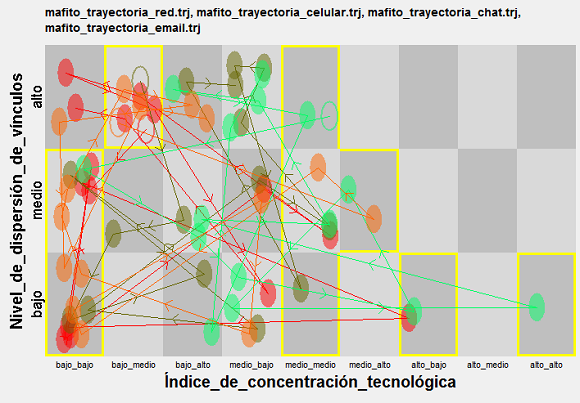

A multi-technological technological system of fixed technology which exists in the trajectory of an anchorage or moderate anchorage technology is always accompanied by two or three technologies which serve as a complement 9 is the case for Mafito 10 .

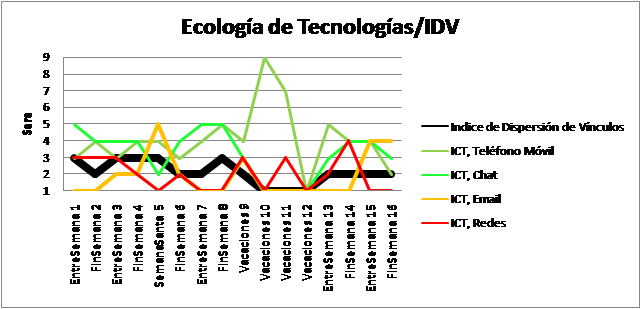

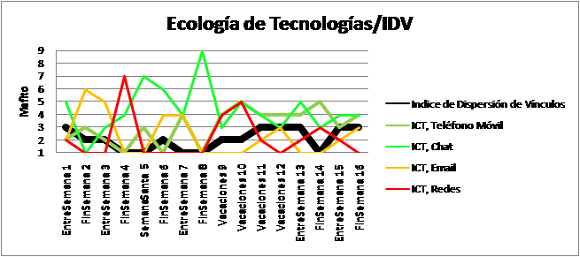

In the case of Mafito it can be appreciated that in the cells situated in the medium and high TCIs (center and right of the grid) chat appears with a great deal of reiteration and, in a lesser degree, email and the mobile telephone. In these ranges, we also see an eventual presence of the social web pages (Image 4). Mafito offers us a structure of relationship in which the four technologies become dominant at some time in the trajectory, although chat occupies the predominant place. This is the case of a multi-technological system in which the centrality of one technology (chat) is always accompanied by other technologies which also turn out to be relevant within the technological framework.

We will not do a detailed analysis for Mafito as in the previous cases, however, it is worthwhile to emphasize how, in graph 4, we perceive the centrality of chat (light green line), always accompanied by other technologies, which also reach significant technological concentration levels. For Mafito, none of the technologies appear clearly in a situation of relegation, as occurs with Nino (mono-technological system of variable technologies) in which the social web pages are always situated in the low levels of the graphic.

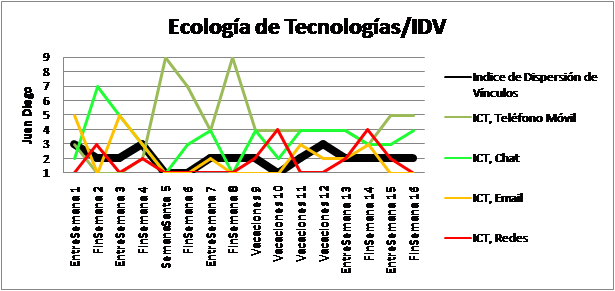

7. Multi-technological System of three or more technologies with moderate anchorage. This deals with a technological system in which two or three technologies are central in the subject's trajectory. In our study, we find this to be the case of Juan Diego 11 .

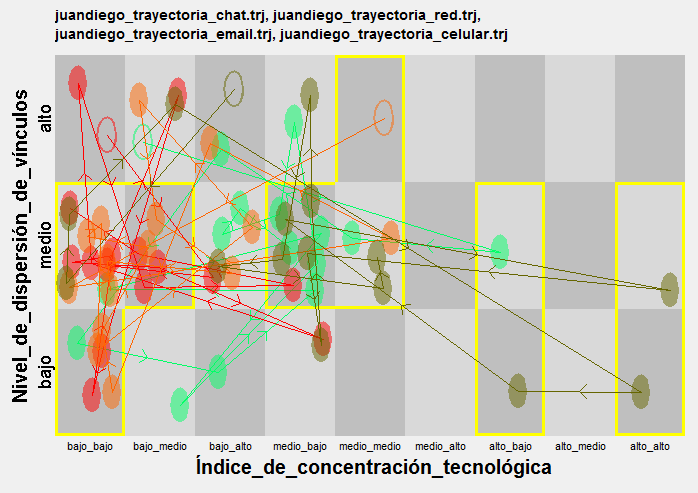

For Juan Diego, there is a tendency toward distribution of events throughout the whole grid (image 5). Although these dispersion results are more pronounced in the case of the mobile telephone and chat, it can also be recognized in those technologies with less centrality such as the social web pages and email. This dispersion speaks of a tendency toward a non-loyal or non-habitual use of one or two technologies; a difference that can be appreciated for Miguel (Image 2). Nevertheless, this tendency toward technological diversity should not make us forget that chat as well as the mobile telephone are the only technologies which occupy the high ranges of the TCI, although, email has a significant presence in periods in which the link space is broad. In general, we find a strong grouping of events in the region to the left of the grid (low ranges, with the presence of all the technologies) and on the right, a diversity of events of three technologies (mobile telephone, chat and email), with the predominance of the mobile telephone. For Juan Diego there is a pole of concentration of events (to the left of the grid) and a wide constellation of events in the center and right regions. The contrast between this structure and that of Sara (Image 3) can be appreciated, with two clear groupings toward the center zone and toward the left. In this sense, we have with Miguel and Juan Diego, extreme versions of a bi-technological system of fixed technology, with centrality of two or three technologies; while with Sara, we find moderate formations in the distribution of events in the grid which end in a bi-technological system of variable technologies.

Without entering and pointing out details about the kind of technological relationship which Juan Diego establishes with each technology period by period, note that graphic 5 shows the centrality of chat and the significant presence of the mobile telephone in Juan Diego's trajectory, accompanied at certain times - by the centrality of email and social web pages. That is, Juan Diego presents a multi-technological system, with behavior patterns of moderate anchorage with chat and the mobile telephone and opportunism with social web pages and email.

8. Multi-technological System of three or more complementary technologies. In this type of system, three or four technologies become complementary throughout the entire trajectory, without any one occupying an outstanding centrality; one technology at the most occupies a place of relegation. In our research, we did not find a subject who reported this system to us.

We have found in our study a predominance of the bi-technological systems of techno-mediation of link spaces, within which it is possible to read types of relationships and singular behavior patterns in each case. Within these cases, the bi-technological systems demonstrate, without exception, anchorage (moderate or strong) patterns of one or two technologies, and variations which range from opportunism in one and moderate anchorage in the other. Probably the bi-technological form may be the most frequent techno-mediation configuration in the social world among the users of the NTR used for linking purposes. Only through more far-reaching studies can the distribution of these patterns be established and differentiated.

In addition to the bi-technological systems, subjects appear within the study with multi-technological systems, also with significant particularities, but who have in common the tendency of non-loyalty as to one or two technologies and the possibility of transacting link space (broad or narrow) and as well, almost permanently resorting to three or more technological mediations. At the opposite extreme, there is the extraordinary configuration of Nino, with a mono-technological system, supported in anchorage relationships with the mobile telephone, with relegation of social web pages and moderate relegation in the case of chat and email. What is characteristic of this mono-technological orientation, as we point out, is the tendency to erase other techno-mediation from the scene, monopolizing all of the link space with only one technology.

This analysis allows us to suggest a gradation in the possible kinds of technological systems of link mediation, distributing them from left to right according to the number of technologies that dominate the system and the stable/unstable behavior of the incorporated technologies (Table 1).

The eight technological systems considered allow us to identify the quantity and complexity of relationships and dynamics which come into play in the connections between urban young people and the new technological repertoires. As we have seen, these relationships consider the number of technologies involved, the level of narrowness or broadness of link space to be transacted and the kind of centrality which each technology has at a given moment. In this way, it cannot be easily affirmed that young people are blindly tied to technologies. The eight proposed technological systems point to ways to think about the enormous weight that social setting plays in the construction of relationships of integrated urban young people and the NTR. The social temporality, with its restrictions and possibilities (weekdays, weekends, three-day weekends), school dynamics with its demands (academic periods, vacations, final exam period, etc.) and the vital circumstances of each subject, point out particular and differentiable courses and trajectories, as we have attempted to demonstrate in this paper.

If a metaphor could be chosen to best illustrate the techno-linking phenomena, it could better be selected from biology rather than from physics or engineering. The phenomena do not deal with interactive networks between people and machines, but rather with authentic ecosystems which tend to reproduce and remain in time, adapting and being adapted to the variations of the environment. These systems remind us that the supposed natural technophile disposition of urban young people, that is their inclination toward technological voracity and their dual tendency now toward a fate of orgiastic and tribal collectivism, or toward a repulsion which is almost socio-pathological, individualist, absorbing and regressive, is nothing more than a reductive representation of the diverse and complex gait of these citizens who plan their destiny and path among varied human and non-human agents.

Studies of a more far-reaching nature with broader, more precise and specific populations and with more data collected through more sophisticated procedures; with data capture through, for example, palm type devices and individual training in order to carry out permanent and continuous records in real time, could offer us a map much more rich in nuance than this presentation, still schematic and limited. T Doctoral thesis from which this analysis is derived proposes that these techno-linking systems (with their nuances and variations) offers clues for thinking about the emergence of another kind of political culture, about which it is worthwhile to investigate.

What we have been shown by carrying out this sustained follow-up in the trajectories of use of chat, mobile telephone, electronic mail and Internet social webs among urban young people, can be summarized in the following terms: if technological innovation, among other things, is attempting to deepen and refine modes of exo-convergence (machine-machine communication) or endo-convergence (multi-machines integrated into one), no less certain and powerful are the innovations which, in use, reveal to us another kind of convergence: socio-convergences; that is, the putting into relationship and genesis of an authentic ecology of machines for the service of purposes which come from the social world and not from the machines' architecture itself. In this study, these purposes refer to the generation and invigoration of social links. The inventiveness and imagination oriented toward strengthening, developing, diversifying and transforming links result in the emergence of a kind of convergence among machines whose explanation and development does not come from the nature and technical ingenuity of engineering in itself, but from the guidelines and social behaviors which differentiate and situate these. However, this reconfiguration as well does not come from the machine itself, but is explained by the genesis of an authentic ecological system, in which some machines occupy a specific niche of use, while others turn to other niches or are partially or completely inhibited and discarded (see Table 1). Beginning with local actions and personal and situated decisions, patterns emerge (ecological configurations) in which each machine occupies a differentiated place in the link dynamics. This is what makes up the kind of social innovation referred to by this paper. Discussion is now open.

1 The Space State Grids (SSG) allows the spaces of a state of a phenomenon to be charted through grids and cells. Each one of the cells of the grid represents one of the possible states that a determined system can achieve through time. What is interesting is that these states are not defined by the software but rather the researchers, dealing with their own research questions, are the ones who define these variables.

2 In the study we speak of the New Technological Repertoires as a way of disassociating ourselves from the conceptions which understand technologies only as concrete devices. The technologies (from the alphabet, printing press, up to the present digital machines) are cognitive moulds which mobilize new forms of relationships of human beings with their interior and exterior worlds (Piscitelli, 1995). They are not simple instruments; they constitute know-how which transforms the lives of individuals (Mumford, 1987).

3 Toward the end of the study (September, 2009) Miguel, one of the participating young people, lost his mobile telephone and experienced a decided break in his own life experience. The loss of his mobile telephone - which he hadn't anticipated - implied the loss of telephone numbers, tips and secrets filed in the memory, recorded photographs and videos, dates of events, birthday records and agendas. During this span in his trajectory, he went on to establish a peripheral and marginal relationship with the social web pages to a much more vigorous and central relationship: Facebook allowed him to recover part of the capacity of coordinating actions and events, in real time, that he had received with the ubiquitous mobile telephone. It was not a question of simply buying a new device. The potential and real linking framework which had brought about through the mediating of his mobile telephone had to be laboriously reconstructed, and he knew that a significant part of such a framework was irrecoverable. But, as well, the relationship with that mobile telephone, the skill with the keyboard, the ringtones previously pulled down from the Internet, the personal configurations and adjustments whose use had evolved into a comfortable and naturalized operation of his telephone, a comfortable relationship over the months, all disappeared when it was lost.

4 In the case of Yulia, another of the participating young people, when we interviewed her for the first time, affirmed that one of her most intense phantoms and terrors was to lose her personal computer through damage or robbery. And not surprisingly, when the refrigeration system of her notebook collapsed in June of 2009, Yulia simply became depressed. Her major work was in danger, the task that she had been forming throughout long and careful work on the computer: a database with books, class notes, bibliographical summaries and duly classified and coordinated university work, electronic addresses, files of family and personal photographs, an enormous framework of labor and academic relationships condensed in her computer. Fortunately, after extensive technical intervention, she was able to recover her work and make use of a new computer.

5The link dispersion index (LDI) indicates the variations in the participants' link space. It points the means by which the set of links that the subject transacts broadens or narrows, while resorting to the use of some of the considered technological mediations.

6 Nino is 18 years old. He is studying Foods Engineering and has enjoyed cooking since he was a child. Technology fascinates him. He devotes a lot of time to deciphering secret Internet codes; he violates codes to get free access to the programs and files he is interested in; however, he is mistrustful of social web pages because he considers that they stimulate false forms of communication. He only chats with people he is interested in and for very concrete topics; except for those with his girlfriend, his chat conversations are always short and to the point. He is fascinated by music and has a systematized file of digital music of more than 1,500 titles.

7 Miguel is a 20-year-old university student. He plays sports and studies technologies. He was a hacker as a young boy. Now he prefers videogames and online games. He has joined several forums through the Internet and belongs to online video-player communities. For Miguel the secret to happiness is to have good friends and to learn to enjoy the present; he doesn't like to be alone or to feel lonely, that's why it is so important for him to build a web of strong and lasting friendships.

8 Sara is 19 years old and loves parties and celebrations; nevertheless she looks sad. She is not satisfied with her present life. She is studying Economics and Finance but her dream is to become a graphic designer. Until a few months ago she spent almost all day connected to the Internet and was in permanent communication with her friends through chat or Facebook. But since she has fallen in love, Sara has begun to use this kind of technology less and less. Now, she says, her world revolves around her boyfriend.

9 When the technology moderately - not centrally - accompanies the other technologies in the treatment of link space in spite of not being central we are talking about a complentary pattern with the technology. This relationship presents itself mainly when, in the majority of the periods, the technology behaves as a Subsidiary Technology.

10 Mafito is a shy 21 year-old girl who has few friends and doesn't go out very much. Mafito spends many hours at the computer. She updates her Facebook at least once a week and she visits and comments in the social web pages of her friends every day. She is also an enthusiastic player of "Farm Town", a Facebook game in which she becomes a "virtual farmer". She devotes one or two hours every day to taking care of the farm: she has to feed the animals, harvest the fruit, fertilize the crops, sell farm products, buy supplies for the plants, etc.

11 Juan Diego is an 18-year-old university student. He has been playing videogames since he was six. He is a disk jockey and soccer player. He hopes to graduate in three years as a Recreation Professional. In order to be a good disk jockey, he devotes time to listening to music and recognizing musical structure. The Internet has been a key tool for learning, experiencing and creating his musical mixes. His greatest satisfaction is to be able to connect with the public and get them to enjoy the parties that he coordinates.