Increasingly, individuals, groups and communities are participating actively in the process of technological innovation. Indeed, the novelty of Web 2.0 technologies and platforms appears to lie in the fact that the user has the possibility to produce - and not just consult - a vast array of content and tools (O'Reilly, 2005; Proulx, 2007; Millerand, Proulx & Rueff, 2010). While users are becoming more and more aware of their ability to make and change technologies to better serve their needs or preferences, participation does not occur automatically for most people.

Embracing the 'participatory culture' associated with Web 2.0 tools and practices (Jenkins, 2006a, 2006b) implies not so much learning how to use participatory tools (like wikis) - since they are relatively easy to handle - as learning how to create, produce and work collaboratively in a networked environment. While traditional views of technology development suggest distinct roles for designers and users (i.e. developing the system versus using it), this conventional distinction tends to dissolve with Web 2.0 platforms and tools, as different applications and information from various sources are imported, personalized and combined by users themselves, leading to user-led or community-led innovations in which both the tools and their uses emerge simultaneously (Bruns, 2008; Jenkins, 2006a, 2006b; Mackay et al., 2000; Millerand & Baker, 2010; Millerand et al, 2010; Von Hippel, 2005). Thus, the potential of these new technologies and their uses for civic engagement and creative expression seems to rely heavily on the users' capacity (both as individuals and as a collective) to engage in collaborative practices as well as in a hybrid 'user-designer' role (Fleischmann, 2006).

This paper discusses the work of a group whose mission is to encourage the development and use of collaborative tools by associative movements. Outils-Réseaux's approach to software and tool development focuses on accompanying and training the groups it works with rather than simply providing technical solutions. Use of collaborative tools by a group is viewed as secondary, and subsequent, to a group's experience with cooperation. The article focuses in particular on a recent experiment among a group of citizens in Brest, France.

Drawing on qualitative research inspired by the principles of grounded theory, we reflect on how an Outils-Réseaux training program for group facilitators participates in community innovation, where the community itself is an essential element of the innovation. We explore the coevolution of both technical infrastructure (tools for collaboration) and the community, and show how Outils-Réseaux mediates between the (social) world of users and the technical world of software developers in three ways. First, Outils-Réseaux uses a 'trickle-down-meeting-bottom-up' strategy in targeting group facilitators rather than the ordinary members of community groups for its training program. In this, it follows a two-step flow information model where facilitators are expected to share their understanding with the groups they guide. Second, training program participants are defined as 'codesigners', as they are trained to choose and customize their tools as well as to experiment with them in practice - following a learning by doing philosophy within a 'logic of attention' specific to Outils-Réseaux's approach. Third, a 'lego approach' to systems development allows for modularity in enabling multiple combinations to fit the singularity of each situation, recognizing the diversity of competencies among participants on one hand, and a potential multiplier effect in networking singular pockets of innovation on the other.

The paper is organized as follows: we begin with a brief review of the literatures in community informatics, user-centered systems development, constructivist pedagogy, and group facilitation using ICTs as they relate to the work presented here. We then describe our methods and research site, highlighting Outils-Réseaux's organization and approach, and providing details on the training program under study. The body of the paper presents the three main points of our analysis summarized earlier. We conclude by outlining the significance of this work for community informatics research and practice.

Community informatics encompasses research and community initiatives that aim to address underserved areas and populations (Gurstein, 2000; Gurstein, 2007; Keeble & Loader, 2001; Williams & Durrance, 2008). In the first world, community informatics has evolved as the notion of access has expanded (Clement & Shade, 2000). From an initial concern with providing free access to computers and increased Internet connectivity or the creation of local community technology centers and programs, it now focuses increasingly on digital literacy in the use of computers and new media applications (http://ctcnet.org/; Keeble & Loader, 2001; Schuler & Day, 2004), empowerment (Kavanaugh, Kim, Perez-Quinones, Schmitz & Isenhour, 2008), and expression of local community identity (Srinivasan, 2006). A number of studies have examined how the introduction of ICTs may help strengthen local community by stimulating collective action or improving local conditions (Alkalimat & Williams, 2001; Haythornthwaite & Hagar, 2005; Schuler & Day, 2004; Shah, Mcleod, & Yoon, 2001).

Local ICT initiatives are often guided by a belief that they will generate social capital among participating individuals. Social capital refers to the idea that the social network of interactions, obligations, trust, and reciprocity among a group of people helps generate resources that they can draw on for individual and communal support (Lin, 2001; Pigg & Crank, 2004; Putnam, 2000; Williams & Durrance, 2008). Since the idea draws much of its philosophical underpinning from a communitarian position (Onyx & Bullen 2000), ICT initiatives generally also aspire to increase participation, equity and community wellbeing. Gaved and Anderson (2006) trace the history of local ICT initiatives from the 1970s forward. Their review of empirical projects/initiatives points to overall positive effects along the five dimensions that DiMaggio and Hargittai (2001) identify as essential in ensuring meaningful usage of ICTS: access, training, skills, support, and purpose.

A key tenet of community informatics is to respect the ability of communities to appropriate and use information and communication technologies in ways that reflect local meanings and goals (Eglash, 2004; Warschauer, 2003). A general trend has been to stress participatory approaches working in collaboration with community members to meet local needs (Merkel, Clitherow, Farooq, & Xiao, 2005).

An extensive literature considering the interplay of technology users, information systems and organizational contexts has developed in the fields of information systems, social informatics and science and technology studies. Traditional, technology-driven conceptions have tended to situate users as one half of the user-developer tandem which suggests distinct, separated stages of work, i.e. developing the system and then using the system. Increasingly, however, particularly with Web 2.0 platforms and collaborative tools, the conventional distinction between designers and users tends to dissolve (Mackay, Carne, Beynon-Davies & Tudhope, 2000; Millerand & Baker, 2010).

End-user computing implies blurring the roles of users and developers when users develop applications themselves (Nardi, 1993), while participatory design views users as co-designers (Greenbaum & Kyng, 1991; Schuler & Namioka, 1993). In discussing Rapid Application Development, Mackay et al. (2000) point to the 'fluidity' of the boundary between user and developer. In short, contemporary approaches emphasize the action of co-design, e.g. practice based design, ecological design, contextual design, design-in-use, collaborative design and performativity (Beyer & Holzblatt, 1998; Suchman, 2002; Bratteteig, 2003; Jackson & Baker, 2004; Jensen, 2004). Furthermore, recent studies of technical innovation, including systems development, portray users as active in the innovation process (Oudshoorn & Pinch, 2003, 2008). As Millerand and Baker (2010) note, "The concept of users has morphed from less-than-competent-system-users to holders-of-local-knowledge and validators-of-system-usefulness, who hold potential as local innovators able to negotiate and arrange realignment and use of standards, applications and systems" (p.140).

From a simple technology-driven point of view, users often are characterized as reluctant to adopt and use technologies; they are seen as lacking in sufficient interest and in need of training. The need for an improved understanding of user involvement (Cavaye, 1995; Flynn & Jazi, 1998; Avison & Fitzgerald, 2003; Howcroft & Wilson, 2003) and developer-user relations (Beath & Orlikowski, 1994; Jirotka & Goguen, 1994; Coughlan & Macredie, 2002; Gallivan & Keil, 2003) is well documented in systems development. Over time, methodologies have evolved from basic technical problem solving approaches to approaches incorporating multiple techniques and use-related activities. The ETHICS method based on the socio-technical systems theory (Mumford, 1983) constitutes the foundation of current user-centered methods, in which social requirements and user participation are emphasized. Users may be seen as evaluators of design decisions (e.g. prototyping approaches), as 'social actors' (Lamb & Kling, 2003) (e.g. ETHICS and soft systems methodology), and as domain experts (e.g. participatory design). Increasingly, information systems are placed within their organizational, social, communicative or pedagogical contexts (Lyytinen, 1987; Iivari, 1991; Iivari, Hirscheim & Klein, 1998; Friedman & Miles, 2006).

In the context of Web 2.0 (participatory Web) technologies and platforms, the potential for user participation is amplified by their ease of use (McLoughlin & Lee, 2007; Murugesan, 2007), which considerably lowers the threshold for participation (barriers to entry). In fact, the premise underlying much of the participatory Web is precisely the possibility offered users to produce - and not just consult - a vast array of content (Proulx, 2007). The ubiquitous use of new collaborative platforms and the social Web (blogs and microblogs, social networking sites, podcasting, and wikis) has become a major feature of the media landscape (Benkler, 2006; Castells, 2009) and a number of recent works in media and cultural studies describe new digital environments as preferred spaces for cultural creation and knowledge sharing (Jenkins, 2006a, 2006b; Bruns, 2008). One of the hallmarks of Web 2.0 platforms and applications is an 'architecture of participation' (McLoughlin & Lee, 2007) that facilitates user-controlled, collaboratively generated knowledge and community-focused enquiry. In these environments, user participation extends also to the production and transformation of the tools and platforms themselves (Millerand et al., 2010). Collaborative platforms and tools common to the participatory Web are highly malleable (Murugesan, 2007), as different applications and information from various sources can be imported, personalized and combined by users themselves.

Conventional principles of social constructivist learning suggest that effective learning occurs when participants interact to create collective activity framed by cultural constraints and practices (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Scardamalia & Bereiter, 2003). This approach, inspired by American pragmatism and developed most fully in the work of John Dewey, assumes that if individuals are to understand and create solutions for problems, they need opportunities to engage with challenging, real-world problems, to learn through participative investigations and supportive, situated experiences, to express their ideas to others, and to make use of a variety of resources in multiple media. In learner-centered pedagogical frameworks, the accent is placed on active participation with others, including peers, instructors, experts and communities (Perennoud, 1983; Lave & Wenger, 1991). By presenting their work to a wide audience, participants are afforded the possibility to appropriate new ideas, and transform their own understanding through reflection (Williams & Jacobs, 2004). They can shape their own informal learning trajectories and also become actively involved in those of others. From this perspective, the community is a key component of the learning process.

McLoughlin and Lee (2007, p. 669) outline the key elements of a 'Pedagogy 2.0' learning environment: a curriculum that is dynamic and open to negotiation and learner input, consisting of 'bite-sized' modules, and blending formal and informal learning; multimodal, peer-to-peer communication using multiple resources; learning tasks that are authentic, personalized, participant-driven and designed, experiential, and encouraging multiple perspectives; in which reflecting on one's learning process is a vital component. They suggest that learners develop a range of digital literacies as they use various tools and multiple forms of interaction to create collective activity and propose several ways in which collaboration around Web 2.0 tools and platforms may encourage learning in tertiary contexts. Gee (2004) refers to affinity spaces where people acquire both social and communicative skills, and at the same time become engaged in the participatory culture of Web 2.0.

McLoughlin and Lee (2007) argue that, by allowing people to interact and share ideas in a fluid way, collaborative tools and platforms can provide the building blocks for an environment that enables multiple forms of support. Similarly, in professional development contexts, several authors have noted that "emergent new Web 2.0... concepts and technologies are opening doors for more effective learning and have the potential to support lifelong competence development" (Klamma et al., 2007, p. 72). The majority of experiments involving collaborative tools and platforms, and lifelong learning have taken place in the context of private enterprise and have focused on knowledge capture and sharing (see for example Fischer, 2011; Efimova, 2004).

Finally, in nonprofit or community contexts, Merkel et al. (2005) have suggested that collaborative tools may be particularly appropriate for the types of activities carried out by community groups. The concept of community innovation (Van Oost, Verhaegh, & Oudshoorn, 2009) in the science and technology studies literature refers to a type of emergent, user-initiated project in which the community itself is an essential element of the innovation.

Importantly, McLoughlin and Lee (2007) note that while Web 2.0 platforms and collaborative tools may stimulate the development of a participatory culture in which there is genuine engagement and communication, careful planning and a thorough understanding of the dynamics of these tools and spaces are essential. Moreover, they argue that the deployment of ICT tools for learning ought to be informed by pedagogies that support learner self-direction. This insight is shared by Merkel et al. (2005) who suggest that, if learning is to have lasting consequences for community development, designers and trainers need to take on less directive roles and fade into the background.

The important characteristics of any learning environment include teaching and various forms of interaction between learners and those who support them. Blandin (2006) reports on a continuing research project whose objective is to clarify the exact function training professionals. Statistical analysis suggests that, among the variety of roles facilitators assume, the role of accompaniment is specific. In particular, a cluster of activities and concerns (managing positioning, managing integration, working on self-directed learning and individualization, monitoring the learners, motivating them) identify those who accompany computer-supported training programs as a special group.

The majority of the literature on small group facilitation suggests that facilitators limit their contribution to process and structure, not content (Gregory & Romm, 2001). Some authors, however, have argued in favor of the active involvement of facilitators in a group's process. For instance, Pasmore (1993) suggests that the facilitator, as a partner in the design effort, may make suggestions as to the design of knowledge systems. Berry (1993) adds that facilitators play a critical role in bringing things to the awareness of the group and should be seen as part of an interpersonal process that aims to shape perception whether consciously or inadvertently. White and Taket (1994: 746) further insist on the importance for facilitators to be critically reflective about their role as facilitators or animators of change.

Much of the work on facilitation draws implicitly on a two-step flow model of communication in which opinion leaders are important intermediaries between mass communication messages and a receiving public (Katz & Lazarsfeld, 1955). Katz and Lazarsfeld argued that people's opinions are strongly influenced by contact with others. Media messages are filtered by these opinion leaders who then act to persuade their followers. Thus, the influence of media (or of a technology) is neither total (reception is selective) nor direct (given the influence of opinion leaders). Time is also an important factor in the model: influence in networks develops over time. The two-step flow is at the base of the diffusion of innovations tradition. Research aimed at understanding how networks of influence play out over the Internet also use this model (Watts & Dodds, 2007).

Our research employs a qualitative approach inspired by the principles of grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). In the context of a three-year project (2009-2012) whose primary goals are to trace the circulation of collaborative tools and knowledge among different groups and to question the articulation of users' and designers' actions in the context of Web 2.0, we have been following the actions of Outils-Réseaux in a constellation of projects. The observations presented in this article are based primarily on interviews with the staff of Outils-Réseaux as well as with one of the initiators of the project in Brest specifically on the subject of the AnimaCoop training program (http://animacoop.net/wakka.php?wiki=PagePrincipale). All interviews were conducted in French, recorded and transcribed. The excerpts presented here have been translated by the authors. We also draw on participants' comments and include an analysis of activity in the wikis developed in the context of this specific project.

Our analysis is also informed by the understanding we have developed of Outils-Réseaux's activities and approach over the course of three years, based on over 50 interviews, observational data, group discussions, and additional documentation. In order to encourage cooperation between the members of our research team, we are performing targeted analyses on eight major themes (such as coordination and tools, relation between designers and users, expertise, governance, contribution, etc.) identified on the basis of our initial research questions, some of which emerge from our data. Interview transcripts have been coded using NVivo software. Each theme is analyzed individually and then collectively, through sharing of our interpretations and writing analysis memos in an iterative process in the tradition of grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Viewing Outils-Réseaux as a partner in our research rather than its subject, we have periodically shared our analyses with staff members, with a view to confirming or infirming our ideas and to enriching them. As will become clearer in the presentation to follow, reflecting on their practice is a key component of Outils-Réseaux's approach, and this paper also represents one element of that reflection.

The French association Outils-Réseaux began in 2003 in response to the growing demand for collaborative network tools from scientific and non-scientific communities in the fields of ecology and the environment. Over time it has enlarged its scope and now concentrates increasingly on exploring the significance of cooperation in a context of social economy and solidarity. The same group of five people has worked together since the beginning, and they are now looking at transforming the association into a SCOP, a sort of employee-owned and managed cooperative. In 2012, Outils-Réseaux deployed its expertise in diversified contexts; it is at the centre of a constellation of innovative collaborative community projects, ranging from e-government projects to networks of musicians to nanotechnologies.

Outils-Réseaux divides its activities into three general categories: software development, a service of accompaniment and technical support (helping groups choose and configure modules that will be useful to them from a toolkit of primarily open source collaborative tools), and training sessions on cooperation and the use of collaborative tools, often in connection with social considerations such as participatory democracy, the particularities of associations or group leadership (animation).

The Outils-Réseaux approach to development has several particularities. First and foremost, it is centered on the groups and individuals that it works with. With a double goal of helping people to imagine the field of possibilities and enlarge this inventory, and of putting the accent on cooperation, the team is guided by its' client association's needs and group dynamics throughout the appropriation process.

Another defining characteristic of the Outils-Réseaux way is its accent on accessibility and simplicity. The team explicitly gears its actions to the 'lowest common denominator' in any group, so that everyone can participate. It will typically imagine its tester population as retired people or students in the third grade of primary school so as to design the simplest possible configurations of collaborative tools. This may involve masking certain functionalities, at least temporarily.

Being attentive to clients' capabilities and their evolution requires a gradual approach to increasing technical skill as well as to learning how to work together. Outils-Réseaux will typically begin by introducing a few, simple collaborative tools and will propose more complex tools only when the people they are working with have become comfortable with the first ones. They also insist on dissociating the experience of cooperation from that of learning how to use computer applications. Thus, they will ensure that the groups they accompany acquire 'small, irreversible experiences of cooperation', independently of the use of collaborative tools. The group has found that this approach works best when they start with face-to-face meetings and small groups.

Outils-Réseaux thus operates according to a logic of assembling a variety of tools into custom packages that best suit the needs of particular groups. This modular 'LEGO approach' allows them to customize their offer. From one group to another, Outils-Réseaux draws from the same general toolkit of primarily, but not exclusively, free and open source tools: wiki spaces, templates, mapping tools, shared agenda, etc. A bare-bones Wiki, called a Wikini, is used as the integrating mechanism to hold everything together. Finally, Outils-Réseaux insists that the final package should be attractive in order to encourage user participation. They insist on a graphic identity, and a fluidity and coherence between the various modules, so that users are not immediately conscious of switching between applications. Use and user experience become the primary considerations.

Located near the western tip of Brittany in northwestern France, the city of Brest is a leader in France in terms of encouraging the social appropriation of information and communication technologies. The city has a population of 150,000 and coordinates its actions with 89 smaller towns and villages in the region. Since 1998, Brest's Internet and Multimedia Expression (IME) Department has promoted a policy and actions for encouraging Internet and multimedia use by the largest possible number of citizens, particularly those who might find it most difficult.1 The cornerstone of its activities is a dense network of public Internet access points (PAPIs). In 2010, virtually all public spaces - libraries, employment centers and community centers, but also unlikely spaces such as residences for the aged, sports centers or food banks - have become PAPIs. Thus, citizens can normally find one of over one hundred PAPIs no more than 300 meters from their homes.

Brest's approach to growing PAPIs illustrates the philosophy underlying many of the commune's computer technology initiatives. The City will provide the equipment and connection necessary to install a PAPI anywhere upon request, but it does not supply staff. The people who are working at a PAPI site, say a food bank, are thus encouraged to take an interest in an indirect manner. They can observe the equipment and people using it from afar and become involved gradually, eventually going as far as to propose local development projects. The local politician at the origin of the IME Department refers to this as a 'logic of attention', meaning that they try to be attentive to people's requests and concerns rather than proposing solutions in a 'logic of intention'. A logic of attention also implies saying to people: "You are important. What you have to say will be of interest to others" (Interview MB June 10, 2010).

This participatory approach to IT enablement is also in evidence in Brest's support for the emergence of local initiatives. Following a call for projects, between 30 and 40 projects are supported annually (average investment $2,500). Most of these projects are carried through and provide concrete results. From the City's point of view, the time and energy invested by citizens is far greater than the monetary cost. The City mobilizes its resources to organize a meeting of all those involved in the various projects, and this networking creates synergies among various people on a regional scale. Brest's strategy thus rests upon multiple, local and small scale initiatives, and the facilitation of links between them.

With its network of PAPI sites and a certain number of ordinary citizens interested and involved in initiatives for community development involving computer and multimedia technologies, the City of Brest sees its role as facilitating connections so that people can help each other acquire further competencies. Brest also coordinates an extensive program of weekly workshops that are offered on demand and in locations of proximity to where they are requested. 2 Here again, the idea is to facilitate so that people who have some expertise in one area can share with others seeking knowledge in that area. The workshops are free and the city pays the instructors who are participants in other projects for the most part. These workshops have been indispensable in promoting the transfer of expertise between projects and locations (Briand, 2010).

Finally, Brest has been particularly active in promoting the collaborative use and free and open source software. Since 2004, it has organized a biennial Forum on Cooperative Uses:3 a three-day colloquium that promotes networking at the national level around questions of cooperation, social innovation and participation.

With its accent on local capacity building in a logic of attention, with its project-based organization of community development initiatives, and with its network of multimedia and IT animators and facilitators, Brest was thus a logical choice for Outils-Réseaux to test its first 'education in action' program. From the City's point of view, the education in action program was a means "to accompany people who want to do something [in terms of group animation] and to acknowledge their importance." (Interview MB June 10, 2010). It targeted people working locally to develop and facilitate cooperative projects in their communities, and was designed to allow them to step back from the action to reflect on their practice. At the same time, it would give them some conceptual tools to increase their competencies and enrich their knowledge in their field of expertise.

Organized with the specific goals of promoting effective use (Gurstein, 2003) and introducing associations to the possibilities of open source software, Outils-Réseaux prepared a program specifically on facilitating collaborative projects. The program was funded as a pilot project under the French government's Uses of the Internet (Délégation aux Usages d'Internet - DUI) program whose objective is to encourage short, online modular training programs for ICT facilitators who will later transfer their understandings to the general public. It also received support from City of Brest and the Regional Council of Brittany through their Innovative Uses of Multimedia for Social Solidarity Project (Multimédia en Pays de Brest, usages innovants et lien social sur les territoires).

Twelve participants took part in the program. The majority had either a professional background or experience with group facilitation. All were working as community organizers in local communities or with special groups such as youth or various social movements. Many were already exploring computer applications on their own, and were seeking to consolidate or acquire more systematic knowledge of collaborative applications, particularly how these tools could be brought to bear in their work. Beyond their interest in collaboration and collaborative tools, one of the prerequisites for participation was to have a specific project in mind that would serve as a test-bed for applying the course content.

The program proposed an original delivery format - a combination of periodic two-day face-to-face workshops, online support, and time and space for experimentation, and was held together with a Wiki platform. In the week prior to the first two-day workshop in early April, the participants and the training team presented themselves on one section of the AnimaCoop site established for the course: their background, their reasons for participating in the program, their hopes, fears, something they were proud of, something they needed.

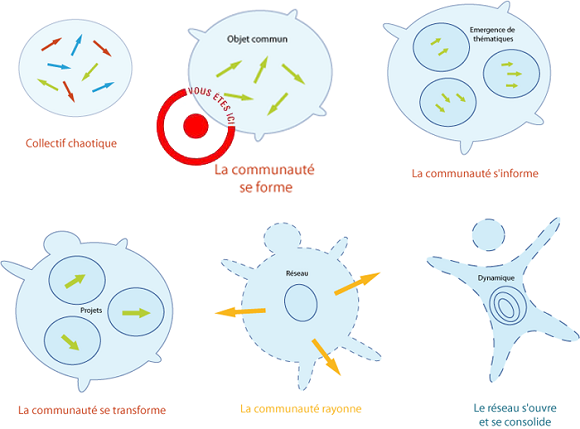

The course was designed to take this small group through all the stages in the life of a network as they themselves worked together over several months:

The first workshop took participants through stages 1 and 2 as they explored notions of cooperation, making the group and its activities visible as well as several collaborative tools. Participants organized themselves into four small groups, according to their personal objectives for the training: leading an ICT project in the community; organizing a work group; creating a network; making a community of contributors more dynamic.

Subsequently, the groups were to work together about three hours per week with online support as required from the facilitators. The objectives of the group work were to work on common themes in a collaborative manner and to explore various collaborative tools in the process. Each participant also spent several hours each week transposing and testing the week's content on his or her particular project. This experience fueled the group discussions. Each group posted a weekly progress report detailing what they had explored, how they had organized themselves, and any difficulties they had experienced.

The course was held together by an online group space, organized with a Wikini. The AnimaCoop space (http://www.animacoop.net) integrated the course components and resources, all of which were visible to the entire group, interns and facilitators alike. All course content, calendar, instructions, participants' and facilitators' self-presentations, was available online. There were also links to various tools and examples of their use in other situations, and spaces that were constructed collectively during the course: a concept box (for developing a common understanding of key concepts), jargon box (glossary), idea box, question box (FAQ), etc. Individuals were given personal Wikini pages equipped with a certain number of tools they could use however they saw fit. Each group also developed a workspace that was accessible to group members and to others outside the group through the site. Since it was wiki-based, each page could be modified by anyone. Thus, while they were learning about cooperation, the participants were also learning how to use a wiki.

During the months that participants were working in their groups, weekly workshops were offered in Brest. Participants attended those that were most adapted to their individual projects. The course content included: sessions on specific tools such as RSS feeds, shared calendars, collaborative writing and document sharing, collaborative visualization tools such as Freemind, MediaWiki, Open Street Map, as well as more conceptual sessions on intellectual property, free and open source software, computer-assisted animation techniques, organizing events, journalistic writing for the Web and social networks.

The collaborative work stage finished at the end of May. After a teleconference whose goal was to share experiences across the groups and to identify common limiting and facilitating factors, each group devoted the month of June to stepping back and evaluating their process with a view to producing a more formal summary account that they could then share and compare with the other groups. A final face-to-face meeting of all the participants was held at the end of June in connection with the 4th Biennial Brest Forum on cooperative uses (http://forum-usages-cooperatifs.net/index.php/Accueil 4ème forum des usages coopératifs de Brest).

Drawing upon our interviews with Outils-Réseaux staff and project initiators, as well as from participants' comments and activity in the wikis, we suggest that the Outils-Réseaux training program participates in community innovation in mediating between the worlds of users and developers in three novels ways: a 'trickle-down-meeting-bottom-up' strategy is introduced to target key intermediary actors, a learning-by-doing philosophy guides the training where participants are positioned as 'co-designers' of their collaborative tools, and a 'lego approach' to system development is adopted to foster modularity and adaptation to local contexts.

Community informatics often implies a bottom-up, grassroots approach to community development. In contrast, the AnimaCoop training program was aimed at group facilitators, rather than the ordinary members of community groups. Participants all had a working knowledge of Internet and an interest in a collaborative approach. Thus, the program did not directly address disadvantaged populations. Like many local ICT initiatives, however, it did seek to strengthen local community by stimulating collective action (Haythornthwaite & Hagar, 2005; Schuler & Day, 2004).

AnimaCoop was established with funding from the French government's Uses of the Internet (Délégation aux Usages d'Internet - DUI) program whose objective was to encourage short, online modular training programs for ICT facilitators who would later transfer their understandings to the general public. Program participants were expected first to learn about cooperation and collaborative tools, and eventually to transfer their understandings to the groups they guide. In this way, knowledge and know-how would diffuse gradually or trickle down, almost automatically. We suggest that the DUI program's target of social inclusion is grounded in a belief that this type of initiative can generate social capital among participating individuals (Lin, 2001; Pigg & Crank, 2004; Williams & Durrance, 2008). The implicit communication model behind the DUI program is that of a two-step flow of information (Katz & Lazarsfeld, 1955) in which opinion leaders (in this case, group facilitators) play an important role in the way messages are diffused among social groups. It explicitly recognizes that social relationships influence how messages are both relayed and received.

In the case of AnimaCoop, the trickle-down approach of the DUI program is tempered by its meeting with the bottom-up, participatory culture in place in Brest. We suggest that this communitarian culture highlights the social dimension of the social capital concept, making the social network of interactions, obligations, trust, and reciprocity a shared resource rather than something held by individuals.

A two-step flow model also implies that the message is not fixed, finite and common to all, but open to a variety of interpretations. The 'audience' becomes an active partner in interpreting and actualizing message content. "There's a step between discovery and mastery [of collaborative tools]. Doing and getting someone to do: two dimensions. The group facilitator needs some time to appropriate the tools before transferring his knowledge." (Participant's comment, AnimaCoop 2010). Before coming to AnimaCoop, the participants were already oriented towards a collaborative approach within their individual projects (see, for example, their initial presentations). Throughout their learning process, they often reflected on how the course content could be useful to their target populations. For example, different participants mentioned the importance of knowing how to get, and keep, the attention of group members. They were also concerned with ensuring the participation of all group members and not frightening users by going too quickly or by proposing tools that might be perceived as being too complicated. These reflections suggest that considerable thought and effort goes into the trickle-down process, at least in the second stage of the two-step flow. They highlights the active role of those involved, not only in selective reception but also in targeted sending, and remind us of Berry's (1993) appreciation that facilitators should be seen as part of a process that aims to shape perception whether consciously or inadvertently.

What better way could there be to learn about cooperation than to experience it? How better to learn about collaborative tools than to use them on a daily basis? We are struck by the high degree of correspondence between course content and its delivery in the AnimaCoop program. In terms of content, the course was designed so that participants would learn about cooperation and collaboration, with or without collaborative tools. They were led to experience all the stages in the life cycle of a network as they worked together over several months. They learnt about collaborative tools by trying to use them in real collaborative situations.

The program was designed to be student-centered, with participants' individual projects being a major component. Having a collaborative project was in fact a prerequisite for participating in the course. This enabled participants to apply what they were learning in the program to their projects immediately, and to be able to ask questions of the training staff as they arose. They were thus involved in action at the same time as they were learning concepts, facilitating the consolidation of experience. This back and forth between action and reflection is a key element of active pedagogy, which stresses autonomy, reflexivity and collaboration (Rouvrais et al., 2004). In short, the AnimaCoop exemplifies McLoughlin and Lee's (2007) 'Pedagogy 2.0' learning environment with its dynamic curriculum open to negotiation and learner input, and blend of formal and informal learning; multimodal, peer-to-peer communication using multiple resources; authentic, experiential, personalized, and participant-driven learning tasks; encouraging multiple perspectives; in which reflecting on one's learning process is a vital component.

Another important facet of the course was participants' work in small groups. These groups provided a space for discussion and the negotiation of shared understandings. As Williams and Jacobs (2004) have also demonstrated, in working together to try out different tools and apply various concepts, and in sharing their experiences in their respective individual projects, participants tested their assumptions and thought through the different ways that a given collaborative application might help a group. They were able to shape their own informal learning trajectories as well as become actively involved in those of others. In this perspective, the community is a key component of the learning process. This is consistent with Merkel et al. (2005), who note that one of the lessons they learned in the context of a training program for community computing was the desirability of interacting around shared activities.

The sharing of experiences served to multiply tacit knowledge across projects as well as to anchor it more deeply. In reality, this aspect of the pilot program was the one that proved most difficult to implement. One participant's comments summarize the general perception:

The training was interesting for its approach, which makes the student an actor. After [the initial workshop,], we were 'let loose' in small groups to experiment with collaborative work and various tools among ourselves. Except, we weren't very used to this type of practice and, with such different projects and concerns, we had trouble coordinating ourselves. The up side of this experience was that it allowed us to observe obstacles to collaboration first hand (lack of time, lack of common goal, participation not sufficiently rewarded, lack of motivation ...). (AnimaCoop participant, 2010)

In terms of infrastructural support, Outils-Réseaux provided 'architecture of participation' (McLoughlin & Lee, 2007) to facilitate user-controlled, collaboratively generated knowledge, and community-focused enquiry. With participatory Web technologies and platforms, the potential for user participation is amplified by their ease of use (McLoughlin & Lee, 2007; Murugesan, 2007), which considerably lowers the threshold for participation (barriers to entry). Based on a Wiki, whose basic principle is that anyone can write in or alter what is written on a page, the AnimaCoop site reflected the ideals of openness and accessibility of information and knowledge. All content was organized according to principles of transparency (anyone could view any page of either the standard course content or the production of other groups and participants), modularity and flattened hierarchy. Particular attention was paid to supporting and recording the group process (posting meeting notes taken on Etherpad, heuristic maps or the collaborative construction of shared vocabularies for example).

The AnimaCoop site provided some, simple collaborative tools - or links to tools - in order to encourage experimentation. In this way, participants were able to selectively appropriate those things they found most interesting or relevant for their individual projects. The platforms and tools common to the participatory Web are highly malleable (Murugesan, 2007), as different applications and information from various sources can be imported, personalized and combined by users themselves. Participants thus became designers in their own right. This supports the observation that with Web 2.0 platforms and collaborative tools in particular, the conventional distinction between designers and users tends to dissolve (Mackay et al, 2000; Millerand & Baker, 2010).

McLoughlin and Lee (2007) note that while Web 2.0 platforms and collaborative tools may stimulate the development of a participatory culture, careful planning and a thorough understanding of the dynamics of these tools and spaces are essential. Moreover, they argue that the deployment of ICT tools for learning ought to be informed by pedagogies that support learner self-direction. Similarly, Merkel et al. (2005) suggest that, if learning is to have lasting consequences for community development, designers and trainers need to fade into the background. They need to find ways for participants to

take control of the design process itself by directing what should be done, by taking a central role in the 'doing,' and by ... maintaining and developing the achievement that is produced. This requires us to find ways to create an environment in which groups can sustain their ability to solve technical problems and direct change themselves(p. 168-169).

This philosophy is at the core of both the AnimaCoop course and the Outils-Réseaux approach in general. The association strives first and foremost to approach any situation by being attentive to its situatedness and particularities. It is operating on what they term a logic of attention rather than a logic of intention. Outils-Réseaux staff propose conceptual and technical tools in ways that promote sustainability: starting small and simple, encouraging their clients to reflect on their practices and to ask questions, enlarging the inventory of possibilities gradually, facilitating use and appropriation.

In the AnimaCoop project, Outils-Réseaux staff acted more like facilitators than trainers. They positioned themselves as partners in the design effort by making suggestions (Pasmore, 1993). In doing so, they demonstrated what has been referred to in the science and technology studies (STS) literature as interactional expertise (Collins & Evans, 2002). While they may not be multimedia or community group leaders, they knew enough about that work to be able to speak to the participants in a language that is familiar to them. This enabled them to present their knowledge about collaborative applications and computer science in ways that were attractive to and easily understood by their target audience. Their interactional expertise allowed Outils-Réseaux staff to position themselves as mediators between the (social) world of users and communities and the technical world of software developers. Their attentiveness allowed them to be responsive and to engage this expertise at appropriate moments.

Each participant in the AnimaCoop project had a project before undertaking the training. Each took the collaborative tools that were proposed and combined them in various ways to fit the needs of their specific projects. This modular approach accentuates the malleability of collaborative ICT spaces (Murugesan, 2007), and highlights the active role of individuals, groups and communities in shaping innovation to fit their needs and according to their constraints.

We suggest that the concept of community innovation (Van Oost et al., 2009) can be useful for describing the type of emergent, user-initiated project in which the community itself is an essential element of the innovation. Most of the participants understood their project as an evolving entity, shaped by the activities of a community of actors who, with collaborative tools, would be simultaneously users and producers. Throughout the process (as well as before and after the training period) they sought to deal with the dynamics of its growth and stabilization by channeling diverse competencies and expertise. While it was their project for the purposes of AnimaCoop, all those involved recognized that they were just there to help it along. One participant expressed the group leader's coordination and alignment role as follows: "In a collaborative project, the group should have a common cultural base in order to participate actively. The group leader has to be able to adapt to the group ... It is essential that he know his group, and he should act as a facilitator." (AnimaCoop, 2010) Finally, in addition to stressing the evolving nature of a project, the concept of community innovation addresses the interrelation between social actors and the technical tools and contextual elements surrounding them. The community is not only source of innovation; it develops simultaneously with the innovation.

In the case of Brest, one important contextual element is the multitude of locally initiated projects. There is not one community innovation, but many. In addition to providing an opportunity for group facilitators to reflect on their practices and explore collaborative tools, the AnimaCoop project was designed to take advantage of this multiplicity. It explicitly brought these individuals together and provided a space for them to meet and discuss around common interests (Interview MB June 10, 2010). Participants invariably noted the importance of their face-to-face meetings. This is in keeping with the City of Brest's strategy of creating synergies between projects and individuals. Local pockets of innovation are the starting point, but there is a multiplier effect in networking them.

This is not to say that multiplier effect is automatic, however. One of the AnimaCoop participants had an interesting reflection on the interrelationship between similar projects:

It is important not to distance the local actors of a mother project that is interesting, already active and starting to bear fruit. The risk is to try to duplicate existing functionalities and uses and consequently to lose people along the way and to create confusion and fatigue among local actors. We need to guard against creating one project to the detriment of another. We need to ensure that the two fit together so that they complement each other.(AnimaCoop, 2010)

Sustainability of local ICT initiatives has been a concern since the inception of the field of community informatics. Externally initiated initiatives have been criticized for providing only short-term benefits to recipient communities (Warschauer, 2003). Growing local projects is a long-term proposition. The local official at the origin of Brest's ICT orientation notes that they have only recently begun to see the impact of a participatory approach. He points to a change in the culture of Brest over thirteen years, and suggests that with the density of ICT developments, new projects are emerging more easily (Interview MB June 10, 2010). It seems that the Brest region is finally benefitting from a critical mass of ICT initiatives, as project facilitators become agents for local development and collective actions appear spontaneously, sometimes without the help of group facilitators (Briand, 2010). This echoes Farr and Papandrea (2004, cited in Gaved & Anderson, 2006) who suggest that initiatives that are combined together into a 'cooperative network' have much better prospects for ongoing sustainability.

The case presented in this paper contributes to a better understanding of how communities may attain 'effective use' (Gurstein, 2003) of ICTs. The Brest region has tried to provide access across the various layers of what Clement and Shade (1998) call the access rainbow: the "socio-technical architecture or model that illustrates the multifaceted nature of the concept of access." The infrastructuring effect of PAPIs responds to the lower levels of the rainbow, while various projects target social facilitation and ICT literacy. AnimaCoop may be seen as one more action within this strategy of attaining effective use (Gurstein, 2003).

We suggest that Outils-Réseaux's specific approach to the development and use of collaborative tools incorporates several elements of interest to community informatics scholars and practitioners. Firstly, the focus of the AnimaCoop program is neither on access at a primary level (the immediate availability of a tool), nor on training and skills (how to use it), but rather on how the tool might fit into a local context. This local context is defined at the outset by the participants. Outils-Réseaux's philosophy is to provide support to these users, and to be guided by their specific needs and diversity of competences. In their devolutionary strategy, the quicker participants take over and make the trainers redundant, the better. What is more, there are multiple contexts in play, as each participant comes to the training with his or her unique situation and perspective. The AnimaCoop training brings them together and asks them to focus on collaborative practices, to interact around shared activities and to learn from each other. The use of collaborative tools by a group is viewed as subsequent to a group's experience with cooperation. This marriage of a 'pedagogy 2.0' learning environment with a panoply of modular collaborative tools provides an 'architecture of participation' (McLoughlin & Lee, 2007) to facilitate user-driven, collaboratively generated knowledge and community-focused enquiry. It encourages participants to become codesigners of their own tools as they adapt, customize and recombine them to suit their purposes.

Secondly, the two-step approach to knowledge transfer and sharing contrasts with many community informatics projects, which tend adopt a bottom-up, grassroots approach to community development. In choosing to accompany group facilitators, AnimaCoop relies on a trickle-down, two-step flow that highlights the social dimension of the social capital concept and positions the social network as a shared resource rather than something held by individuals. The 'audience' (in this case, the participants) has no choice but to become an active partner in interpreting and actualizing message content.

Finally, through its promotion of both conceptual and technical tools that enlarge the range of possibilities and give communities greater control over the use of technology in their organizations, Outils-Réseaux participates in local innovation. By banking on user-initiated projects, the Outils-Réseaux approach offers one path towards sustainable community innovation. The process is dynamic in that a group's composition, expectations and priorities evolve as they experience collaboration and gain experience (and confidence) with collaborative technologies. As the AnimaCoop program is adjusted and offered again in Brest and other regions, the ultimate goal remains: encouraging an emerging civil society in which ordinary citizens become more and more actively involved in shaping their technical and social environments.

This paper is based on research conducted in the context of a three-year project funded by Canada's Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC).