The 'Urban Spacebook' Experimental Process:

Co-designing a Platform for Participation

- Researcher, Department of Civil, Structural and Environmental Engineering, and Department of Geography. Trinity College Dublin, Ireland. Email: baibarac@tcd.ie

INTRODUCTION

Urban planning, and urban development more generally, are moving towards a more participatory direction due to both external and internal pressures. The World Commission on Environment and Development and the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit culminating with Agenda 21 (United Nations, 1992) pointed to a need for greater dialogue involving many public stakeholders at different levels-from the local, regional and national levels through to the international level. Nevertheless, some argue that policies and planning interventions aimed at local sustainable urban development have failed to consider the thoughts and actions of urban residents. This represents a "major obstacle to the pursuit of an 'overall sustainability' in practice" (Jarvis, et al., 2001, 139). It is also important to consider that cities are transformed through the everyday practices of their inhabitants, who collectively add meaning to places through their rhythms and use of space (Kuoppa, 2013).

Rapidly developing Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) offer interesting opportunities for improving knowledge regarding the everyday life practices and experiences of local residents, thus potentially informing and enhancing local planning and urban sustainability processes. Moreover, the rapid expansion of social media and web 2.0 applications has opened up additional opportunities for people to be involved in planning their environments through the uses of seemingly everyday, mundane technologies and outside formal planning processes. For example, ICTs can support methodologies such as Soft Geographic Information Systems (SoftGIS), which facilitates the collection of residents' perceptions about the quality of their environments and the creation of an experiential, or 'soft', data layer for use in urban planning (Kahila & Kyttä, 2006, 2009; Kyttä, et al., 2013). While these forms of participation are acknowledged in fields such as participatory e-planning, more research needs to be done in relation to how digital tools used for participation are being designed; particularly how existing technologies are appropriated and linked together as part of broader participatory information ecologies (Saad-Sulonen, 2013).

This article advances research in the area of participatory e-planning by extending work on user participation to the design of digital technology, along with focusing on inhabitants' everyday life experiences of urban space (i.e. experiences embedded in everyday life practices). The author seeks to examine innovative approaches in the design of ICT platforms for public participation. Two specific questions are being addressed in this paper: First, how might the communication of experiences embedded in everyday life practices, such as movement through the city, enhance participation in urban planning? Second, what kinds of tools might facilitate better public participation in urban planning processes? Inspired by open-source digital sharing culture, the research presented here approaches the design of a potential digital platform as a collaborative process, undertaken from the perspective of urban inhabitants. The article focuses on the design process of the "Urban Spacebook" platform and discusses three spatial-technological experiments, which informed this concept. It is argued that an Urban Spacebook platform offers opportunities for sharing everyday life experiences of, and in, urban space. It also offers opportunities for enhancing the co-governance of such city spaces, by creating an arena where ordinary inhabitants and city decision-makers can come together to discuss and envision possibilities for the future development of these spaces.

The article will start with an outline of the theoretical background of the research, followed by a brief discussion of the Dublin context where the experimental co-design approach was developed and implemented. The methodology-which includes three distinct spatial-technological experiments-will then be described. Building on these experiments, the article then proposes the prototype Urban Spacebook ICT platform for public participation. The paper concludes with a discussion of the wider implications and challenges of the proposed platform.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

One way of enhancing public participation in local planning processes, and indeed for stimulating greater participation in the democratic process, has involved the use of GIS in public participation initiatives, or Public Participation GIS (PPGIS) (Sieber, 2006). PPGIS's proponents acknowledge that a planning process cannot be based exclusively on technical knowledge, but that it must also consider citizens' needs and collect the experiences of those living in a local territory (Magaudda, et al., 2009). Developments in ICT have provided additional opportunities for gathering data concerning residents' perceptions of the quality of their local environments. In combination with PPGIS, these approaches give rise to new and interesting possibilities regarding the collection of 'soft' data, which can be usefully employed to complement 'hard' planning data (Kahila & Kyttä, 2006). One example is the SoftGIS methodology-developed at Aalto University-which has been tested in several Finnish cities as a way to collect experiential knowledge concerning urban environments (Kahila & Kyttä, 2006, 2009; Kyttä, et al., 2013).

At the same time, the rapid expansion of social media and web 2.0 applications has introduced a paradigmatic shift in relation to civic participation and the ways in which geographic data are produced. It is now difficult to differentiate data 'producers' and 'users' in an environment where many participants function in both capacities. One example of this is the growing impact of collaborative online mapping tools in which the notion of 'map user' no longer implies a singular consumer of cartographic communication (Goodchild, 2007). Platforms such as Google Maps and OpenStreetMaps encourage individuals to develop interesting applications using their own data, while the increased availability of Global Positioning Systems (GPS) and websites such as Flickr allow users to upload and locate photographs on the Earth's surface by latitude and longitude (ibid). Such developments open up opportunities for new forms of participation outside formal face-to-face meetings and consultations, in everyday life situations (Horelli, 2013). Moreover, they lay at the core of the recent field of participatory e-planning, which acknowledges multiple participations (Saad-Sulonen, 2013).

However, while the expansion of social media and web 2.0 has increased the scope and toolkit available for citizen participation, it has also introduced new challenges. For example, while many e-participation projects are initiated to increase citizens' (particularly young citizens') participation in politics, few to date are apparently successful. Sæbø et al. (2009), for instance, believe that one reason for the failure of such digital public participation projects is a lack of involvement of citizens when designing and developing the e-services-in essence, people do not necessarily become more willing to participate simply because internet-based services are provided for them.

More than representing a mere technological development, web 2.0 environments and the forms of interaction encouraged by social networking sites (e.g., Facebook, Twitter) have brought about social evolution (ibid). These media's characteristics include principles of free access to information, self-organisation, mass collaboration, non-exclusive services and user participation, which are also reflected by the 'open-source' digital movement. Changes in how people interact and collaborate with each other in the online world have introduced new demands in relation to e-planning initiatives and urban planning more generally. As Saad-Sulonen (2013) argues, there is a pressing need to expand the concept of participatory e-planning to collaboration in the actual design of the digital technologies involved-a form of participation that has sometimes been neglected in the e-planning and urban planning discourses. Two considerations are also seen by Saad-Sulonen to be particularly important: participation as design-in-use (i.e. users are involved in the design also during ICT use and not only at the initial stages of the design process); and the state of the current technological landscape including online tools and possibilities for digital map mash-ups (ibid).

Besides these technological advances and participatory developments in the urban planning field, it is also important to acknowledge that, at a local level, "governing takes place through the everyday and the material practices of urbanism" (Bulkeley & Castán Broto, 2012, p.5). Urban space is thus transformed not only through urban planning or policy interventions, but also through the everyday practices of city inhabitants. As well as rational considerations and perceptions of one's surroundings, understanding experiences embedded in everyday life practices can also contribute to studying how people use their local environments1, and in turn, to how the city is shaped through the practices of everyday life. Rather than representing a feature that can be achieved by city planners alone, a sense of place tends to be created by the users of those spaces, inter-subjectively through their rhythms and everyday practices (Kuoppa, 2013). At the same time, familiarity and attachment to place can motivate people to become more involved in improving their local neighbourhoods (or those areas that they use in their daily lives) and, thus, to participate in local planning processes (Manzo & Perkins, 2006). Moreover, everyday life practices such as urban walking offer opportunities for finding a much needed common ground between planners, inhabitants and other stakeholders when discussing spaces in the city and their future development. Besides formal meetings, consultations or surveys, first-hand interactions with those spaces targeted by planning interventions offers opportunities for learning about the local environment and better understanding its problems, potential and local resident's needs (Halprin & Burns, 1974; Kuoppa, 2013). Yet, it can be argued that the planning literature has generally overlooked the importance of everyday life practices and experiences (Kuoppa, 2013), with few exceptions (e.g., Jarvis, et al., 2001). The next section extends this discussion about the interactions between local urban practices and potential participatory digital tools in the context of Dublin, Ireland.

The Dublin urban context

The Irish capital, Dublin, represents a useful case study partially because the current programme for local government in Ireland promotes the use of online platforms and social media to engage with the citizens (Department of the Environment, Community and Local Government, 2012) as a means for addressing concerns about limited public participation in planning (Taskforce on Active Citizenship, 2007). This programme, for example, identifies a platform (FixYourStreet.ie) that was prototyped initially in Dublin and which enables the public to report non-emergency issues such as graffiti, road defects, street lighting faults, water leaks or drainage issues, and litter or illegal dumping to the local council via an online map. Moreover, Dublin City Council (DCC) has experimented with novel approaches in the design of public services and urban development, such as through the 'Street Conversations' approach, which employs on-street questionnaires to explore what people like, dislike or could be improved about a particular area (Conroy & Mooney, 2011; Conroy, et al., 2012); as well as through 'Your Dublin Your Voice', an online citizen opinion panel seeking feedback and suggestions on a range of issues that impact on quality of life in the city (Cudden & Sheahan, 2011). Both approaches are aimed at informing urban development plans and policies. While these examples illustrate the progress made regarding public engagement, some important limitations of these approaches can also be observed. Rather than improving participation and using the benefits of interactive mapping and social media (e.g., active user participation and collaboration), the negative reporting promoted by FixYourStreet.ie reflects (and continues) the reactive forms of participation noted within the Irish planning system, such as 'negative objecting' (McGuirk, 1995). The two DCC initiatives noted here represent a step forward through their aims to include citizens in identifying potential local improvements before they are developed into plans. However, in these approaches communications remains top-down and unidirectional. For example, the (Your Dublin Your Voice) panel members respond to topics established by experts; and the (Street Conversations) survey respondents do not have the opportunity to engage in how their input will be integrated into future DCC policies or plans.

Building on the theoretical background outlined above, the Urban Spacebook digital platform concept and the co-design process through which it emerged has been designed to address the limitations in DCC civic engagement processes. The methodological approach and influences that shaped this process are discussed in the next section.

METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH

The methodological approach undertaken to address the two previously noted research questions was to start from the ground-up, with three 'experiments' that focused on everyday life experiences of urban space and include potential users in the design of a potential platform for participation. This approach builds on research into creating open and adaptable ICT solutions for collaborative urban planning (Saad-Sulonen & Botero, 2010; Saad-Sulonen & Horelli, 2010). Moreover, such an approach was also seen to provide a useful and needed alternative to the existing tools for participation employed by city planners in Dublin.

Acknowledging the importance of everyday life practices and experiences in the transformations of urban space (Kuoppa, 2013), the three experiments discussed below were designed to examine how resident's everyday life experiences of space might be elicited and represented. In turn this process served to inform the development of the Urban Spacebook platform. The research employed a dynamic approach, which focused on those experiences associated with resident's movement through urban space. As Kevin Lynch noted in, The Image of the City, "people observe the city while moving through it" (1960, 47). Our approach suggests that traditional approaches to urban planning-typically using static analyses of urban phenomena-can benefit from a more dynamic perspective, such as the lens of urban daily mobility (Jirón, 2008). At the same time, relatively recent developments in ICT practices, such as location-aware technologies, arguably have made everything and everyone potentially locatable (Gordon & Silva, 2011). This implies that the city's dynamics can now be fruitfully explored by using Global Positioning System (GPS) technology as a valuable tool to track people's interactions with the city through movement (Calabrese & Ratti, 2007).

In addition to this choice of a dynamic methodological lens, representational techniques and strategies were also considered in our work. As the study included GPS technology for tracing movement through space, it was considered useful to search and gain inspiration from fields with traditions in GPS-linked mapping. One such field is the locative art domain, where GPS technologies have been used for over a decade as a way to explore movement and the environment, and their relationships. The emerging art forms are typically collaborative (between artist and the audience) and participatory (requiring participation in order to take place). Their representations and aesthetics can be employed as a way to affect discourse (e.g., Amsterdam RealTime, noted in Polak et al., 2002), or can become part of interventionist approaches in which the explicit intention is not to produce more data but instead to intervene in provocative and creative ways that may lead to change (e.g., Traverse Me, noted in Wood, 2010).

Moreover, since this study focused on experiences of space and aimed to include potential users in the design of the platform, inspiration was sought from the creative and collaborative planning approaches prototyped in the late 60s in the United Sates by Lawrence and Anna Halprin. For example, their 'Take Part' process aimed to facilitate citizen-formulated decisions in a more egalitarian design approach, by enhancing people's creativity and awareness of their environment (Merriman, 2010). It also sought to develop a "common language" amongst those taking part, which was seen to be necessary in order to make collaborative decisions about the future of the community (Halprin & Burns, 1974). Halprin's senses-focused process was employed in the Dublin research as a way to enhance and bring to the surface what may already be experienced, but in an unconscious way, in movement through (and interactions with) urban space. Inspiration was also obtained from situationist practices, such as dérive (Sadler, 1998), as a way to interrupt the 'usual' by slowing down, and provoking new experiences of and in city space. This approach also reflects the links between situationists and locative media art practices (McGarrigle, 2010), on which the Dublin research project draws in terms of representational techniques. The next section discusses three ICT-linked experiments undertaken in Dublin which characterized the co-design process and in turn helped to shape the development of the Urban Spacebook platform.

THREE CO-DESIGN EXPERIMENTS IN DUBLIN

The co-design process for the Urban Spacebook platform included three urban spatial-technological experiments variously using ICTs and which build on the methodological approaches outlined above. These three experiments varied in their participatory and collaborative aspects, as well as in the extent of their spatial focus. The approach was aimed at making the transition from a researcher-mediated process to one that encouraged interactions among the participants through the use of web 2.0 tools, with the aim of enhancing their role in the design process. The methodology used for each of the three experiments undertaken in Dublin will be described in the three sub-sections that follow.

Experiment 1 - Hybrid Diary-Camera-GPS Study

This experiment-undertaken from September to November 2011-consisted of a hybrid diary study, which combined GPS-tracking, photography and text inputs, and was developed as an individual exercise (i.e. conducted and discussed individually with the participants). The experiment was aimed at obtaining a written and visual image of the participants' daily interactions with the city through movement, as initial exploratory step in the research process. Diaries were kept by eight Dublin-based volunteers2 over one full week of their choice, including the weekend and days off.

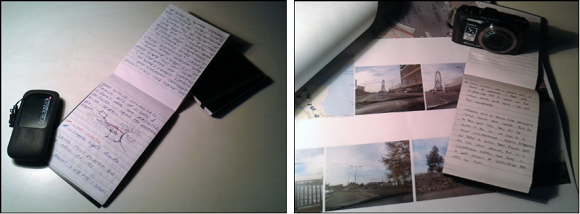

The participants were self-selected, since the aim of the study was not to offer statistically representative data but rather to explore how everyday experiences of space might be elicited and represented, The diarists were given a toolkit containing a blank notebook, a GPS-tracking device3 and a GPS-enabled digital camera4 (Figure 1). They were asked to trace all of their movements over the chosen week, to record their experiences in the notebook and to take photographs of any elements of the city that they felt was meaningful in their daily experiences.

The analysis included examining the diary contents and interviews with the participants about their experience of diary-making. The analysis of the photographs focused on their subject(s) (e.g., landmarks, parks, positive or negative features) and whether these subjects were mentioned in the diary written text and how. As basis for the interviews, the participants were presented with maps showing their own contributions and also collective input (i.e. GPS tracks and photographs mapped using ArcGIS Explorer Desktop, and visual representations produced using Adobe Photoshop). Because the interviews were conducted individually, this was a way of encouraging reflection not only on their own journeys, but also on other diarists' input as expressed in the map synopses.

Experiment 2 - Collaborative Workshop

The second experiment-undertaken in June / July 2012-consisted of a collaborative three-week workshop taking place in Dublin5, and was aimed at making the transition between the insights of the diary study and the extended use of online and mobile technologies. It explored ways of gathering and visualising experiential aspects of the city and movement through it, and on representing them in a collective way mediated in a digital environment (i.e. a map-based digital prototype).

Building on Halprin's process (Halprin & Burns, 1974) and situationist practices (Sadler, 1998) the methodology for this workshop experiment included a series of 'urban awareness walks', which took place in a designated area of Dublin. The test-bed area was centred on the location of the workshop and was sufficiently large to allow for different routes to emerge, but also relatively small so that the research area could be covered on foot (approximately 1.7 x 0.75 km). Moreover, the research area included parts of the re-developed docklands where DCC had conducted 'Street Conversations' (Conroy, et al., 2012). The walks were conducted both individually and in groups and ranged from open, exploratory dérives (individual, Figure 2) to guided, pre-determined routes (group, Figure 3). Their aim was to encourage direct interaction with space, to enhance an awareness of how the area was being used and to open up opportunities for a better understanding of the local area's qualities, deficiencies and potential.

Inspired by the diary study, the participants tracked their routes, this time using a free GPS-tracking app, EveryTrail6, which they installed on their smartphones. They were also encouraged to take photographs of features of interest encountered along the way, and to make notes of their experiences. Moreover, the participants were given stickers to place in those locations that they identified to be of interest (e.g., the fence of a derelict site that could become a garden). They were asked to photograph the sticker as placed by using the app, which generated a unique geo-tag; and they had the option of adding a comment (one the app) to briefly explain their locational choice. Together with the GPS tracks, these photographs and comments were added to an initial digital platform prototype developed later in the workshop.

Experiment 3 - Online Study

The third and final experiment was conducted as an online study-undertaken for a one week period in November / December 2012-which examined the potential of locative media and collaborative online mapping tools to translate and adapt the previous two studies to a web 2.0 domain-thus making the transition to a fully digital platform (i.e. Urban Spacebook). In order to do this, two existing platforms were employed: first, a trip-recording mobile application (EveryTrail, used also in the previous experiment), which the participants installed on their smartphones; and second, an online mapping platform (Crowdmap)7 through which participants could visualise their individual and collective inputs. Similar to the previous experiments, ten volunteers who offered to participate used these digital tools to track their routes through the city (this time over a common week); to take photographs; to make notes about features that were relevant to their daily urban experiences; and to share their contributions on the group website. The use of web 2.0 tools was aimed at enhancing the participants' role in the ICT design process, and also at making the transition towards wider public participation.

RESULTS OF THE THREE DUBLIN DIGITAL EXPERIMENTS

This section presents the results of the three spatial-technological experiments identified above, by highlighting those findings that helped to inform the Urban Spacebook digital platform concept. The three experiments sought to address the first research question of this study, namely, how the (digital) communication of experiences embedded in everyday life practices, such as movement through the city, could potentially enhance participation in urban planning. The three subsections below further detail the key findings from the three digital experiments in Dublin.

Results of Experiment 1 - Hybrid Diary-Camera-GPS Study

The diary and camera study highlighted a number of interesting issues regarding inhabitants' habitual interactions with the city. One finding which was particularly revealing was that the diary-making as a whole (i.e. the diary-making and the reflective interviews) led to seven out of the eight participants reporting a heightened awareness of their knowledge and daily use the city. The exception was one diarist, who noted being interested in street photography and therefore to usually paying close attention to his surroundings. This heightened awareness effect, which was discussed as part of the post-diary reflective interviews, varied in length. For example, one participant experienced an enhanced awareness only during the diary-keeping week due to an otherwise busy everyday life; for another diarist the effect involved taking more notice of her surroundings, especially those features she omitted to note in the diary although meaningful for her impressions of the city. Furthermore, she became more aware of the effects her travel choices had on her children-specifically, the differences in their experience of their surroundings when brought around by car rather than by bicycle.

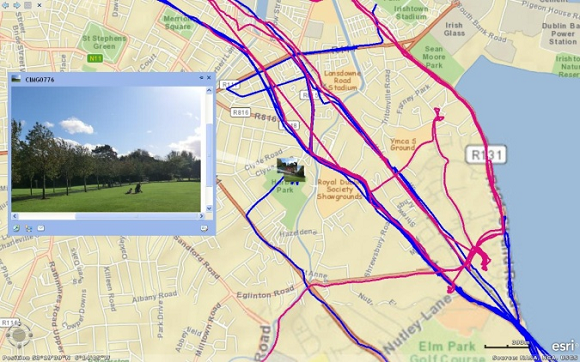

This experiment reconfirmed that besides concrete, rational factors, such as getting from A to B, people's movements throughout the city are also affected by experiences embedded in everyday practice, typically difficult to be consciously rationalised or recognized (Spinney, 2010) because of their habituality. Diarists' examples include experiences of noise and the visual effects of street litter, which prompted them to avoid certain areas; or places from which their children could watch trains passing by and which they included as part of their everyday routes. Taking part in the diary study enabled some of these experiences and related aspects of the city to be noted and expressed by the diarists, as discussed above. This took place 'on-the-move' through the lens of the camera, which brought about an increased sensitivity to what was being captured; and was also linked to the post-diary activity, by visualising the collective GPS-based maps (of all eight diarists), which prompted further discussion and reflection. When seeing their individual traces in the context of those of the other diarists, the maps made participants more aware about their own uses and knowledge of the city. They realised that they shared their everyday routes with others and also that the same space may be seen, known and used very differently by different people. For example, one diarist realized that he might take the same route everyday without properly knowing its resources or amenities-as was the case when another participant who shared his daily route identified a local park that was previously unknown to the first diarist, even though he lived nearby (Figure 4).

Thus, even if they were conducted individually with the diarists, the map-based discussions suggested the importance of sharing experiences and local knowledge among the participants, and indicated the potential value of expanding the diary-making process to a wider audience, which could generate engagement amongst those taking part. This was taken forward in the next two experiments, which focused on facilitating interactions between the participants and exploring tools that are now pervasive (e.g., locative technology and collaborative online mapping tools) as a way to enable this collaborative process.

Results of Experiment 2 - Collaborative Workshop

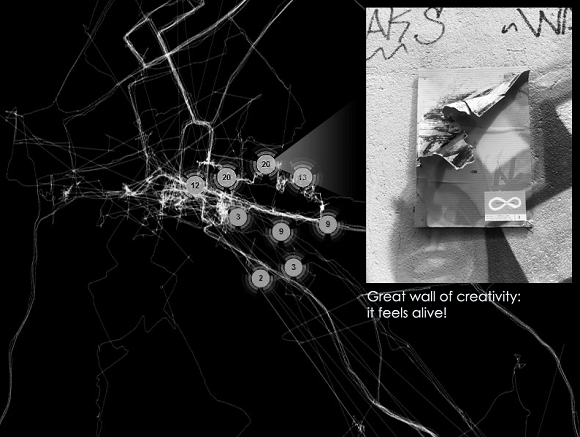

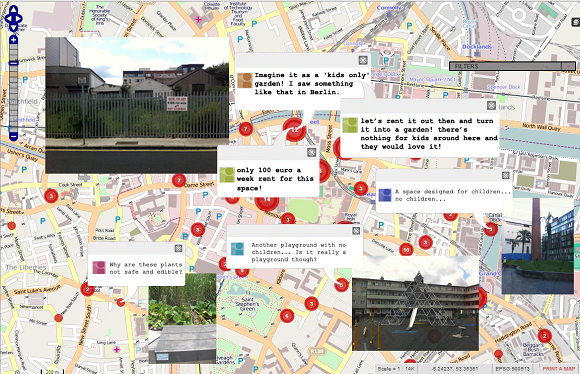

While the individual urban awareness walks were more passive in terms of participant engagement (i.e. individual route mapping), the group walks had the important characteristic of concluding with collective discussions of the individual experiences through organized reflection and brainstorming sessions. These workshop discussions indicated that although experienced (and reflected upon) individually, the urban walks offered a common basis for discussing the local city area where the workshop was conducted and opened up ideas about its potential by encouraging first-hand interactions with urban space. The experiment also led to an initial digital prototype8, an online map, which served to visualise the collective contributions of the diarists (i.e. their GPS traces, photographs and notes taken using the EveryTrail app). One of the features of this prototype map was the absence of a 'base-map'. Instead, building on the diary study, the city was seen as being 'drawn' by inhabitants' movements (i.e. GPS traces) and 'coloured' according to how each person experienced it, mediated via their photographs and notes about experiences along their routes (Figure 5). This recalls the concept of 'city image' (Lynch, 1960), which suggests that each person holds a different 'mental map' of the city based on how it is experienced. The prototype is therefore conceptualized as a re-drawing of the city based on inhabitants' movement, and it encourages sharing and discussion of individual experiences and local knowledge of the city.

By providing a space where individually-created maps can be shared and visualised together, a digital platform can offer opportunities for enriching and expanding individual city images. In turn, not being limited by one's own experience through a process of learning from each other might also increase individual awareness of how the city is used and experienced by others, thus open up alternative possibilities. Moreover, the prototype also allows users to identify, annotate and discuss routes and urban spaces that they consider interesting or with unused potential. Such spaces, which may be neglected by formal planning and policy-making procedures, are important for how people move through and experience the city; using a digital platform, they can be identified by inhabitants (i.e. made visible) and brought to the attention of the city council decision-makers.

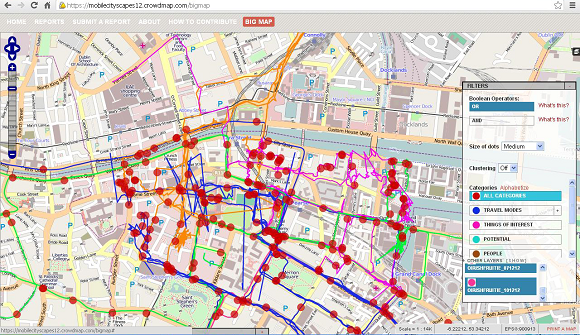

Results of Experiment 3 - Online Study

The limited time of this experiment (i.e. one week) did not allow for deep interaction and extensive communication among the participants, their contributions consisting mostly in recording and sharing their routes through the city. However, there was some dialogue on the group website regarding features such as the speed of a route and participants' personal knowledge about particular places. The possibility of commenting on other group members' input (i.e. GPS tracks and photographs) in similar ways with other commonly-used social media, e.g., Facebook, proved particularly useful for this. Moreover, the collective maps proved useful for visualising all the input in one place. Crowdmap, the platform employed to create these maps, is particularly suited for localized content, e.g., geo-tagged photographs, but less so for GPS tracks (Figure 6). This suggested the need for a more dynamic platform, which could allow contributors to upload both localized and also continuous data points (i.e. GPS traces).

The two platforms used in this experiment indicated the value of merging the communicative and networking aspects of social technology (e.g., Facebook) with the visual aspects of maps. This allows bringing conversations conducted through social media channels in one place, on a map, which makes such conversations locatable and easier to relate to. However, while this experiment was part of the design process for a platform that could be used in planning, feedback from the participants indicated that people might actually be more willing to use such a tool if it was not targeted specifically, or primarily, at urban planning. This concern referred particularly to its potential uses as a crowdsourcing platform for commercial interests. Instead, what was seen to motivate people to use it was the possibility of sharing, and finding out about, 'quirky' features of routes or spaces in the city (e.g., unusual building details, 'secret' gardens or quiet places in the city). This could offer a personal interpretation of the city, make one's habitual journey more interesting and even make it appear shorter when perceived to be long. The overall results therefore address the first research question and provide valuable findings, which inform the 'Urban Spacebook' platform concept put forward in the next section.

THE 'URBAN SPACEBOOK' PLATFORM

The three experiments discussed above were conducted as part of a co-design approach to devising a participatory digital platform, which employed mobility as a 'conversation starter' for expressing and sharing experiences of the city. The first experiment indicated the need for increasing awareness of individual habitual interactions with the city as a prerequisite to communicating such experiences. This was achieved 'on-the-move', through the lens of the camera, and also through the use of collective maps, developed by seeing individual mobility traces in the context of others. Locative media and collaborative online mapping tools can extend this process to a wider audience and enhance awareness at a collective level. As illustrated in the second experiment, an online collective space offered opportunities for enriching one's personal local knowledge of the city and it opened up alternative possibilities (e.g., routes or uses of space). It also allowed for identifying spaces of interest or with unused potential from the perspective of their everyday users, which can augment the knowledge of city planners. Moreover, the last experiment highlighted the value of merging the communicative and networking aspects of social media with the visual features of maps. This can enhance interaction among users so that a collaborative process can take place, while making the content of the discussions locatable.

By alternating between spatial/physical and technological/virtual features, and encouraging first-hand interactions with urban space, the three experiments identified the importance of 'provoking' an enhanced awareness of local urban knowledge. This highlighted the importance of those urban experiences embedded in everyday practice and sometimes taken for granted to come to the surface and be expressed. Thus, the three experiments indicated the importance of complementing technology (e.g., GPS tracking) with reflective methods (e.g., written diary) and/or spaces for reflection (e.g., collective maps). This approach allows individual experiences to be expressed and shared among users-and potentially between city inhabitants and decision-makers.

Based on the results of the three spatial-technological experiments, the prototype ICT platform, dubbed Urban Spacebook, is discussed here in relation to the second research query of this study. As the name suggests, Urban Spacebook is conceptualized as an interactive map-based platform-essentially a website and a mobile app-which merges the communicative and networking aspects of social network technology (e.g., Facebook) with visual representations of movement and city experiences (e.g., GPS-based maps). At a broad level, the concept employs mobility as a starting point for discussions about the city and GPS technology as a tool that can facilitate a re-mapping of the city from the perspective of its inhabitants. The prototype consists of an open-source web 2.0 platform (i.e. a map-based website and a mobile application) for geo-tagging user-generated content. Users can share their experiences and connect with others through interactive maps that include their uploaded photos and notes (e.g., images, text, sound recordings) plotted along GPS traces of their routes. Besides findings from the experiments conducted, the website and app features and potential uses are also informed by feedback from the participants to the experiments, and from DCC planners to whom a prototype platform was presented. Each of the two core elements of the Urban Spacebook concept are further elaborated upon in the two subsections below.

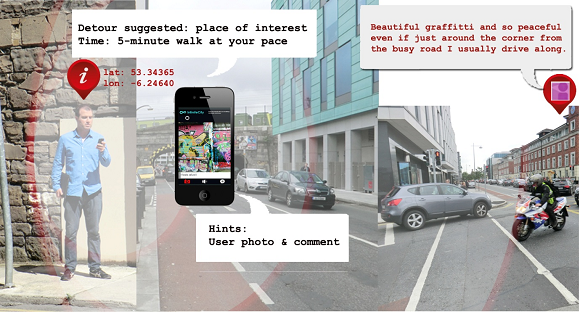

Mobile App

The mobile app offers improved functionality compared with the experiments in two key areas: it allows for the provision of location-related information and data logging on the move. Drawing on the work in Experiment 2, the location-aware feature encourages the user to take a detour from his/her usual routes or ways of experiencing them, and discover what others may have shared (Figure 7). As suggested by the participants in Experiment 3, this may include 'quirky' features, local uses or activities that may be found in the area. This can offer an augmented experience of the city, which can break the routine of everyday movements and allow users to notice features of routes usually taken for granted, as discussed in Experiment 1.

Moreover, looking at everyday spaces with the eye of a tourist (or from the perspective of other residents) can enhance one's awareness of the environments people inhabit and their familiarity with such places (Gordon & Silva, 2011). By becoming more aware of their environments through first-hand experiences, users can better define existing issues and suggest relevant improvements such as through the use of geo-tagged photographs and comments. Furthermore, increased familiarity with, and attachment to, places in the city can motivate efforts to improve them and enhance participation in related planning processes (Manzo & Perkins, 2006). Rather than promoting 'negative objecting' (e.g., FixYourStreet.ie), the mobile app can enable a proactive role for those who use it. The possibility of proactive engagement was an important feature for the planners to whom the prototype was presented as it can contribute to a more positive and collaborative relationship between them and city inhabitants.

The city council could also use the app to communicate with the users 'on-the-move', through a form of location-based notifications. By using social media instead of surveys, a conversation could take place and also expand-not only between the council and the individual user, but also amongst other users-in a potentially less resource-intensive and more comprehensive way than by conducting on-street surveys (e.g., Street Conversations). Such discussions would be geo-located and time-related, thus allowing the contextualisation and documentation of potential issues and suggestions. This can make city inhabitants' participation more flexible and spontaneous, and offers opportunities for transforming their civic engagement into an ongoing process, which can enhance current forms of participatory planning consultations (presently undertaken at discrete moments in the Irish planning processes).

Map-based Website

Building on the findings of Experiment 3, the map-based website offers a space where individual users can come together through the generation of collective data visualisations, interactions and communications among users. Besides making visible shared routes (and potentially different types of local knowledge regarding them), the visual and interactive aspects of the digital map website can bring to light shared concerns or ideas, and connect users that might not have been able to meet or enter a conversation otherwise. This interaction can develop into suggestions for improvements that are meaningful to them, such as the 'kids'-only garden' suggested by some of the participants to Experiment 2 (Figure 8). While some of these proposals may be dealt with by groups of inhabitants, others can be brought to the attention of the city council. These may refer to spaces, buildings or other urban features that are currently outside of formal city plans-yet mediated through the map, can make planners aware of their importance for the ordinary city users. As noted by the planners with whom the prototype was discussed, this could offer opportunities for new ideas regarding the public realm that might not have occurred to them otherwise.

The visual features of the map-based website also represent a way to spatially indicate the outcome of the public engagement process and monitor progress. For example, an increased concentration of GPS traces could show an increased use of a formerly avoided area or improved pedestrian links. This was an important feature for the DCC Principal City Planner9 interviewed in relation to the prototype, which he saw as a potential way of complementing current quantitative metrics with visual representations of 'soft', abstract data. The map website also allows the recording and documenting of the process through which a proposal has emerged, thus improving its transparency-something which currently is not possible. The concluding discussion, in the section below, addresses the implications of the three experiments in Dublin and identifies the possibilities raised by the proposed Urban Spacebook prototype.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This article has discussed how the communication of experiences embedded in everyday life practices, such as movement through the city, could potentially enhance public participation in urban planning. It also described a prototype tool-the Urban Spacebook platform- as a medium which could facilitate such participation. This experimental and co-design approach arguably represent a potentially innovative and effective addition to recent endeavours to expand the role and means for participation of ordinary inhabitants in the planning and development of their everyday urban environments.

The aim of this work-to understand people's experiences of their local urban environments-is not new, as illustrated by the renowned work of Kevin Lynch (1960) and the more recent developments involving the uses of web-based GIS technologies to facilitate the collection of location-based experiential knowledge (Kahila & Kyttä, 2006, 2009; Kyttä, et al., 2013). The Dublin-based research discussed in this paper was intended to extend these aims to those everyday practices, which are difficult to access, including unconscious elements of people's everyday interactions with the city (Brown & Spinney, 2010). In order to access everyday life experiences of city spaces, our study combined spatial and technological aspects with qualitative and reflective methods, and undertook this process on two levels-the individual; and the collective level. The hybrid diary-camera-GPS experiment sought to elicit and represent everyday experiences of urban space at an individual level. The two subsequent experiments investigated possibilities for conducting a similar process of digital data collection and spatial representation on a broader scale-a collective level. The diary study (Experiment 1) indicated the value of enhancing awareness of participants' surroundings (e.g., everyday routes) in order to access everyday experiences of space. This notion was extended further in the urban awareness walks (Experiment 2), which were explored as de-constructions of experiential aspects that could be transposed into digital features. The alternation between physical and virtual features highlighted the need to complement technology (e.g., GPS tracking) with reflective methods (e.g., written diary) and/or spaces for reflection (e.g., collective maps). This allowed individual experiences to be expressed and digitally shared among users-and potentially between Dublin city inhabitants and decision-makers.

The experimental co-design process indicated how everyday experiences of urban space might be communicated using technology. Moreover, the tool put forward, Urban Spacebook, offers opportunities for enhancing the co-governance of urban spaces which people use in their daily lives, by creating a digital arena where they can discuss such spaces and their future development with the decision-makers. The research employed the notion of mobility as a 'conversation starter', which offers a common starting point for expressing and sharing experiences of the city. When complemented by technology, mobility becomes a tool that can facilitate a re-drawing of the city from the perspective of its inhabitants-by using GPS-tracking, inhabitants can produce user-generated maps of the city. While GPS technology has already been used in tracing city maps with the help of inhabitants (e.g., OpenStreetMaps), this paper suggests a new purpose for its use. Sharing mobility experiences and drawing city maps can become part of a collaborative process between ordinary city inhabitants and city decision-makers, aimed at rebalancing power relations and at placing inhabitants in a co-productive capacity. Rather than using ICTs only to gather or count data, technology can become a tool for a collaborative production of knowledge for, and about, the city. Beyond the present role of data-generators, Urban Spacebook offers therefore opportunities for ordinary inhabitants to become part of the important process of local knowledge production about urban spaces and their future development.

Thus, the Urban Spacebook encourages a framework for a form of urban governance that is based upon a collaborative, ongoing and iterative process, as distinct from the usual one-time participatory initiatives (Jarenko, 2013). This conceptualization is inspired by open-source approaches, which place an emphasis on collaborative forms of knowledge production rather than consumption (Haque, 2007). From this perspective, ordinary inhabitants are seen as co-producers of the city together with the decision-makers, and not simply as passive participants in planning processes or mere consumers of services. This suggests that residents can become active participants in the development of their city, by sharing its quintessential (yet very little known) aspects-what city living is about and how it is experienced in daily life. Moreover, expanding on the notion of GPS-drawing (Wood, 2010), such digital maps can become a way of critically engaging inhabitants in the development of the city. For example, its visual qualities with concentrations of traces and 'energy / activity points' clusters can be employed to draw attention to those spaces that have been neglected and raise awareness of potential solutions, as envisaged and needed by their inhabitants and users.

In summary, the prototype Urban Spacebook platform potentially provides viable opportunities for sharing everyday life experiences of urban space and also for enhancing the co-governance of such spaces, by creating an arena where city inhabitants and city decision-makers can come together to discuss and envision possibilities for future spatial development. We suggest that future work needs to be conducted to develop the platform beyond its conceptual stage (outlined here), by potentially prototyping it in various urban locations in order to compare different contexts and to experiment with different types of data; different visualisations; and distinct applications such as commercial applications or local public initiatives from city governments or community groups. Challenges to implementing such ICT prototypes are also acknowledged, including issues around data privacy and local motivations for initial and ongoing participation in urban planning processes. For example, GPS data represents a sensitive issue because of its potential negative connotations, such as surveillance (Crang & Graham, 2007). Participation could also be challenging if the platform is perceived as a one-way data mining tool, not giving something back to its users; or it could be limited to particular groups, thus deepening contrasts between city areas and leading to biased results. However, based on the findings of the experiments conducted in Dublin, it is believed that if the platform is carefully designed and offers individuals a meaningful exchange for their time and effort these challenges could potentially be overcome.

Finally, the experimental and co-design approach discussed in this paper illustrated how the communication of everyday experiences of urban space could enhance participation in urban planning. By alternating between physical and virtual features, the experiments discussed above indicated the need to complement digital technologies (e.g., GPS tracking) with physical reflective methods (e.g., written diary) and/or spaces for reflection (e.g., collective maps). These approaches allow individual experiences to be expressed and shared among users-and potentially between city inhabitants and decision-makers-representing the substance of the collaborative approach proposed. By using mobility as a conversation starter and GPS technology as a tool, ordinary inhabitants can produce user-generated maps of the city, which can complement those drawn up by city planners. This potentially frames a new form of urban governance, which is based on a collaborative, ongoing and iterative process, and could expand the role of city inhabitants to that of co-producers of the city together with the decision-makers. Acknowledging the need for deeper cultural and practice changes regarding how public participation is implemented in urban planning processes, the Urban Spacebook platform embodies the potential for enhancing interaction between those who inhabit and those who govern cities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank the research participants for their time and contributions to this study, Dr Niamh Harty and Professor Anna Davies (Trinity College Dublin) for their support in my work, and the reviewers for their invaluable advice and help with this article. Infinite thanks also to the Interactivos?'12 workshop collaborators: Gabriela Avram (University of Limerick), Alessio Chierico (University of Art and Industrial Design Linz), Christine Gates (independent artist), Eulàlia Guiu (University of Girona) and Kathryn Maguire (independent artist); and technical advisors: Tim Redfern (independent artist) and Max Kazemzadeh (Gallaudet University).

This research was part of a Graduate Research Programme in Sustainable Development, in conjunction with the award of a grant from the Irish Research Council (former IRCSET/IRCHSS).

ENDNOTES

1 A useful discussion regarding the

differences between the rational, deliberative thinking

system and the irrational, intuitive and 'auto-pilot'

system as related to people's decision-making processes

can be found in the work of psychologist Daniel Kahneman

(e.g., Kahneman, 2012). In relation to the study reported

here, this refers to the difference between rational

considerations such as way-finding and perceptions of

one's surroundings, and those aspects of everyday

practices of movement, which are habitually repeated and

contribute to 'auto-pilot' forms of interaction with the

city.

2 The diary participants had been involved in

the previous research stages of a wider study into

mobility practices and participatory approaches to urban

planning (e.g., Baibarac, 2014).

3 The GPS tracking device used in the diary

experiment was a Trackstick Mini

(http://www.trackstick.com/products/mini/intro.html).

4 The camera model used in the diary

experiment was a Casio Exilim Hybrid-GPS.

5 Experiment 2 was conducted during a workshop

entitled Interactivos?'12, part of "Dublin Hack the City"

Exhibition. This was organized as an open call by Science

Gallery, Dublin, together with MediaLab Prado, Madrid

(http://sciencegallery.com/interactivos).

6 EveryTrail is a free iPhone and Android app,

which allows tracing one's route on a map, geo-tagging

photographs and uploading the GPS files on the user's

webpage. Users can comment and vote on others' trips and

photos, create groups and share their trips via Facebook

and Twitter (http://www.everytrail.com/).

7 Crowdmap is a ready-to-use online mapping

platform, which allows users to set up their own projects

without having to install the platform on a web server

(https://crowdmap.com/).

8 The digital prototype was developed with the

help of Tim Redfern (independent artist) using open

source code-OpenStreetMap and Leaflet, among others,

during the Interactivos?'12 workshop in June / July 2012.

The website was populated with the data collected by the

participants using EveryTrail.

9 The DCC Principal City Planner has overall

responsibility for strategic / forward planning and

development management in the city, and has introduced a

sustainability framework as part of the current

Development Plan, based on Natural Step principles. The

City Planner was interviewed by the author in January

2013 in relation to the research reported here.