ARTICLE

Folkloric Voices in Neorealist Cinema: The Case of Giuseppe De Santis *

Giuliano Danieli

Sound Stage Screen, Vol. 2, Issue 1 (Spring 2022), pp. 31–70, ISSN 2784-8949. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. © 2022 Giuliano Danieli. DOI: https://doi.org/10.54103/sss16776.

In 1952, the screenwriter and film theorist Cesare Zavattini (1902–1989) published “Alcune idee sul cinema” (Some Ideas on the Cinema), which is generally regarded as the retrospective manifesto of neorealism. The article extolled the “factual” nature of the new Italian cinema, notably its quasi-documentary approach to the harsh reality of poor people living at the periphery of the Nation, the use of nonprofessional actors playing themselves, the adoption of dialect, and the abolition of the cinematic apparatus. However, Zavattini failed to acknowledge that the music and voices of subaltern subjects also merited consideration, if their world was to be faithfully captured on screen. [1] Antonella Sisto, among many others, has ascribed this inattention to sound to the supposed “lack of audiophilia” of neorealism, deriving from its “monosensory, visual foundation.” [2] This formulation of the problem surely contains a degree of truth—in his article, for instance, Zavattini adopts a language that refers almost exclusively to the semantic field of “seeing”—, but it relies too much on the dubious polarization “image vs. sound,” which may be unhelpful for a more nuanced understanding of neorealist filmmaking. Zavattini’s inattention to sound derives not so much from the supposed hierarchical superiority of the image as from the absolute precedence given to the broader concepts of plot, narrative, and characters. Thus, it would be more accurate to introduce the issue of music and sound in neorealist film from the perspective adopted by Richard Dyer in his pivotal article “Music, people and reality,” where he noted that a discrepancy existed between the plots, situations, and environments portrayed by neorealism—“a movement presumed to be about creating a cinema genuinely expressive of ordinary people’s reality”—and their seemingly conventional soundtracks. [3] In other terms, Richard Dyer has observed that neorealism often relied on well-established norms of film-scoring practices, despite the fact that, on every other level, it wanted to overcome cinematic convention. The soundtracks were the work of composers such as Alessandro Cicognini, Mario Nascimbene, Goffredo Petrassi, Giuseppe Rosati, and Renzo Rossellini. Their late-romantic or modernist symphonic style clearly contradicted the purported aim of providing a transparent recording of the reality of the films’ protagonists—sub-proletarians, disadvantaged workers, beggars, peasants, fishermen, and so forth. In fact, the “music of the people” (folk tunes, popular and military songs, religious chants) featured in only a small minority of neorealist works, most often as source music. A fundamental incongruity lurked behind the fact that while neorealism’s ambition was to reduce “the distance between the films and their protagonists”, its typical subjects “cannot speak for themselves: music is needed to speak for them. But that music will not be their music.” [4] Neorealist soundtracks, notes Dyer, established an implicit hierarchy: the point of view on narrated events, usually expressed by non-diegetic music, was entrusted to a musical idiom that was foreign to the cultural world of the subjects portrayed; as such, their voices risked being drowned out and disempowered by the voices of the filmmakers.

While agreeing with Dyer’s general observation, I think that the assertion that neorealist films were oftentimes deaf to the music and voice of the people portrayed deserves further thought. The case of Giuseppe De Santis (1917–1997), one of the leading figures of Italian postwar cinema, helps complicate Dyer’s account. [5] De Santis allocated a special place to folk songs and melodies, which were often the vehicle through which he allowed his protagonists—peasants and proletarians—to express a socialist worldview (one that he himself shared). In 1953, De Santis even planned to make a film entitled Canti e danze popolari in Italia (Folk Songs and Dances in Italy). The project, rejected by Goffredo Lombardo, head of the film production company Titanus, was conceived as a celebration of folk culture and music through the cinematic representation of traditional songs and dances from various parts of Italy as collected, recorded, studied, and edited by the director and his assistants. [6] The rationale of Canti e danze showed analogies with the ethnographic and ethnomusicological field research that was being carried out across Italy around this time. In 1948, ethnomusicologist Giorgio Nataletti founded the CNSMP (Centro Nazionale di Studi di Musica Popolare, currently known as the Archivi di Etnomusicologia) at the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, which promoted fieldwork campaigns that made it possible to record and study an unprecedented amount of folk music. The most famous of these expeditions was the one with Alan Lomax and Diego Carpitella (1954–55), who travelled backwards and forwards between South and North Italy, collecting thousands of folk songs and drawing an extensive map of Italian musical folklore, which ignited a growing interest in this multifarious repertoire, especially among leftist intellectuals. A few years earlier, Carpitella had joined Ernesto De Martino’s team expeditions to Basilicata, Calabria, and Apulia. Such experiences were informed by the idea that the cultural (and musical) world of the folk deserved to be studied and rescued from imminent extinction, not least because it was considered the bearer of positive values that the hegemonic capitalist system was obliterating. [7] The ideology and concerns of these campaigns had much in common with De Santis’s Canti e danze and, more generally, with his rural cinema. As I will show in this article, De Santis’s films proved important agents in the process of elaboration and popularization of discourses about folk music in postwar Italy, and the director attempted to empower voices that until then had remained unheard. The undeniable fact that this process was all but unambiguous makes it even more urgent to study it in depth.

In keeping with this tenet, this article listens to, and looks at, the folkloric voices in De Santis’s Caccia tragica ( Tragic Hunt, 1947). [8] This film—as the others De Santis made in the following years, such asRiso amaro (Bitter Rice, 1949) and Non c’è pace tra gli ulivi (No Peace Under the Olive Tree , 1950)—focuses on the cultural and political conflict between peasant communities and rapacious oppressors—the former group representing anti-hegemonic socialist values, the latter being symbolic of capitalist individualism. In the first part of the paper, I consider how music in Caccia tragica provides De Santis with a fruitful means of establishing the dichotomy “folk culture vs. capitalism” that was to become a trope between postwar Italian Marxist intellectuals, ethnographers, and ethnomusicologists who proclaimed the subversive power of the folk. Not only did De Santis’s representation of folk music sanction such discursive divide; as I shall show, at certain key junctures De Santis’s films short-circuit the relationship between folk music and capitalism. I therefore ask whether blurring the boundaries between these two opposite poles might help to arrive at a more nuanced understanding of the ways in which folk music was perceived in 1950s Italy. By posing this question, my contribution resonates with Maurizio Corbella’s recent article on the musicscape of Riso amaro, which “unintentionally reveal[s] fields of tension between the cultural values, hierarchies, and divides” in postwar Italian culture, notably the precarious position occupied by popular music. [9]

The second part of my study stretches beyond music alone by considering the broader folkloric soundscape invented by De Santis. In particular, I claim that the sounds of bells, whistles, and clapping are just as important as music in constructing the anti-hegemonic values and force of De Santis’s protagonists. Dyer’s point on music in neorealist films—his implicit question about the disempowerment of the Other’s voice—is complicated by this more comprehensive scrutiny of De Santis’s soundtracks, which testifies to the director’s attempt to empower the subaltern through a number of sonic elements that would become characteristic of folkloric soundscapes in Italian film. To substantiate my analyses of music and sound in Caccia tragica, I do not limit the discussion to the released version of the film, but I also look at archival documents that shed light on De Santis’s and his collaborators’ creative process. Furthermore, I complement the discussion of this film with the examination of the unpublished script of Noi che facciamo crescere il grano ( We Who Grow Grain, ca. 1953), which I could study at the Fondo De Santis of the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, Rome. This unfinished project proves not less crucial to understand De Santis’s construction of the folkloric voice. [10]

Folk Music in De Santis’s Caccia tragica

De Santis always demonstrated a marked interest in folklore and peasant culture. [11] Between 1947 and 1950, he shot the so-called Trilogia della terra (Trilogy of the Land), comprising three films set in rural areas of northern and central Italy (the minefields and paddies of the Po Valley and the Ciociarian mountains) which focused on farming communities and their stories of solidarity and resistance (Caccia tragica, Riso amaro and Non c’è pace tra gli ulivi). In some ways, De Santis’s works can be seen as a continuation of the rural strand that, under the Fascist regime, had resulted in films such as Alessandro Blasetti’s Sole (Sun, 1929) and Terra madre ( Mother Earth, 1931). Yet, whereas Fascist cinema generally portrayed field workers in an idyllic fashion, exploiting their alleged authentic rural traditions to reinvigorate a sense of national pride, De Santis’s was a cinema of crisis that aimed to delve into the open wounds of postwar Italy, notably by criticizing the status quo from the perspective of subaltern people and by extracting socialist messages from his rural exempla. [12]

De Santis’s cinematic output seems both to be informed by and act as a precursor to principles that resemble the Gramscian notion of “ nazional-popolare,” which became a common theme in Italian intellectual debates during the 1950s. Mention could be made of a few essays by Antonio Gramsci in his Prison Notebooks, published in 1950: for example, “Osservazioni sul folklore” (“Observations on Folklore”) encouraged the critical study of folk culture as a historical, subaltern “conception of the world,” one which was autonomous and in opposition to hegemonic culture. [13] In notebook 21 on popular literature, Gramsci introduced the concepts of “national-popular” art and that of the “organic intellectual.” He claimed that “a national-popular literature, narrative and other kinds, has always been lacking in Italy and still is” because of the gulf that existed between the worlds of intellectuals and ordinary people; an “organic intellectual” should arrive and finally bridge the gap between these universes, so as to guide (and be guided by) the folk towards higher levels of self-awareness and socio-political agency. [14]

Although De Santis was unaware of Gramsci’s vision, his work was not far from it, given that he wanted to make a national-popular cinema that could give voice to and empower the subaltern. [15] However, as many scholars have noted, his films do not offer an entirely straightforward rendition of the world in which his characters move. De Santis’s was a “poetic realism,” a re-elaboration of reality that enabled a number of questions about society to emerge in a quasi-Brechtian way. [16] The director himself defined his films as an instance of hybridity: “hybridization of genres is, in my opinion, the key to my cinema”. [17] Thus, while narrating stories of peasants, he adopted a cinematic language that was also informed by American popular movies and Russian cinema. [18] His poetics of hybridity often blurred the line between established cultural divides, such as the one that saw folk culture as essentially opposed to the capitalist universe.

Such ambivalences speak of the director’s own contradictory impulses, and leave a permanent mark on his films. This also applies to their music, the soundtracks interspersing preexisting folk repertoire (or, better, what at the time was considered to be “musica popolare” [folk music]), popular music, and newly composed film scores in symphonic style. In the pages that follow, I ask what values were attached to these musical repertoires (especially folk music and popular music) and explore what they reveal about the different ways in which postwar Italian culture listened to the folkloric voice. Given the space available here, I limit my discussion to Caccia tragica, the first chapter of the Trilogia della terra.

Caccia tragica takes place in the Po Valley immediately after the Second World War. It is a parable of national reconstruction and class solidarity after years of devastation caused by the conflict, a story of desperate veterans returning from the front and poor peasants trying to unite to start a new communal life built on socialist values. There are four main protagonists. Giovanna and Michele are peasants working in a cooperative and, along with the community of field workers, they represent the film’s positive pole; representing the bad side of human nature is another couple, Daniela and Alberto, who are bandits. At the beginning of the film, the latter couple commits a robbery, stealing the money needed by the cooperative to lease land and agricultural machineries, and kidnapping Giovanna (Michele’s wife), whom they take as a hostage. Daniela and Alberto embody individualist and consumerist values, posing a threat to the peasant community’s peace and unity. Yet Alberto is an ambiguous villain: although Daniela, his lover, has convinced him to become a bandit, he had actually been Michele’s comrade during the war, sharing the shocking experience of the German concentration camps with him. As such, there is an unspoken bond between Alberto and Michele, preventing the former from being totally subsumed by an individualist vision of the world. Indeed, as the film unfolds, we witness Alberto’s gradual repentance. Although he initially supports Daniela and tries to flee with her from the community, who “hunt” them down to retrieve the money and rescue Giovanna, he ultimately gets tired of his criminal life, sabotaging his partner’s evil plans and freeing their hostage before then embracing the cooperative’s socialist values.

The soundtrack for Caccia tragica includes several popular songs and folk melodies as sung and heard by members of the farming community (“ canti popolari,” as the director often calls them in the script). These pieces are associated with various rural traditions, as well as political songs heard and sung by the portrayed farmworkers. Alongside these, several cues composed by Giuseppe Rosati also punctuate the action. Rather than having a mere denotative role, popular music is here infused with values that help define the characters and develop the sociopolitical message that De Santis had in mind. He typically associates folk music with the good characters, while reserving the use of popular music—the voice of capitalism, of mass culture—for the villains. In so doing, he contributed to the musical articulation of the “folk music vs. capitalism” dichotomy, which, as noted above, was becoming fashionable at the time. Yet the boundary between these two poles is not always as clear-cut as one might imagine.

Fig. 1. Giuseppe De Santis, Caccia tragica (1947). Still frame at minute 00:42:19 (see note 19).

The film’s central scene provides a good example of how De Santis creates a link between popular music and the villains. At minute 00:41:07, [19] we see the bandits with their hostage Giovanna in a country villa, a secret refuge where they have gathered to discuss their criminal plans. The place is filled with visual references to consumerism, such as advertisements, a bottle of champagne, and a radio (see figure 1). We hear the broadcast of a series of well-known wartime songs: the swing tune “Begin the Beguine,” the patriotic American march Stars and Stripes Forever by John Philip Sousa, a partisan song (“Avanti siam ribelli”), and the Nazi-tainted tune “Lili Marleen” (which had become popular during the war both in Germany and among its enemies). As Guido Michelone has observed, De Santis here wants to “narrate and explain, through the music, the Italian situation at the time” by drawing attention to the increasing “intrusion of Americanism at the level of mass culture, a model that was replacing both the Fascist rhetoric and genuine folk culture.” [20] As in De Santis’s other films (such as Riso amaro), the presence of musical reproduction devices (such as the radio or the gramophone) symbolizes the threat posed by mass culture, particularly American popular culture. [21] In this scene, the radio seems to commodify American music, war, and resistance songs by featuring them in a continuous stream that reduces all music into mere objects of aesthetic consumption.

Daniela, the antihero of Caccia tragica, is passionately fond of the radio. As she talks to Alberto about their crimes and future aspirations, she expresses her individualist vision of the world and desire to become famous like a star (“today everyone is thinking about us [because of our robbery]”, she exclaims). This moment is accompanied by “Lili Marleen,” which she is particularly fond of (indeed, “Lili Marleen” is her nickname). Daniela is thus linked with a tune that, although appropriated in the 1940s by the Allied troops, also had strong Nazi connotations. [22] More importantly, she is associated with the world of popular music as epitomized by the radio. Alberto’s position towards “Lili Marleen” and the radio, by contrast, is somewhat different. When the song starts, he tries to turn the device off (figure 2), yet Daniela insists the song be allowed to play on. These simple gestures clearly signal the gap between the two protagonists and their cultural models. Alberto oscillates between Daniela’s individualism and the allure of capitalist culture on the one hand, and the more traditional values of solidarity embodied by Giovanna and Michele on the other. The parable of sin and repentance that ultimately leads him to embrace the cooperative’s communal life at the film’s ending is therefore prefigured in this scene on a musical level—i.e., as an attempt by Alberto to reject popular music (and the radio) along with the values which are implicitly attached to it.

Fig. 2. De Santis, Caccia tragica. Still frame at minute 00:47:40 (see note 19).

While Daniela is unequivocally associated with “Lili Marleen,” Alberto is here musically characterized by the partisan song “Avanti siam ribelli.” It is surely not coincidental that this music—which obviously had a positive connotation for De Santis as well as, most likely, much of his audience—begins to play just as Alberto tells Giovanna of his guilt over his immoral life. As observed above, Alberto is not a real villain and Daniela’s dangerous appeal proves for him to be only a temporary departure from the good values associated with his rural upbringing. The allure of capitalism brings him to the verge of losing contact with the “genuine folk”—i.e., the peasant community. The scene thus seems to represent Alberto’s unsettled and confused state of mind through a musical analogy. “Avanti siam ribelli” is a reminder of the folk’s revolutionary power, and yet its juxtaposition on the radio to American popular music and “Lili Marleen” suggests that it has been commodified. In linking “Avanti siam ribelli” with Alberto’s remorse, De Santis talks of the positive values embodied by this music; at the same time, he imagines a scenario in which the partisan song could be corrupted (just like Alberto when he embraces Daniela’s values), becoming an object of mere aesthetic consumption as it enters the domain of popular music mediatized by the radio.

In other scenes in the film, folk music serves as a powerful agent of moral development and solidarity. In the sequence that precedes his final repentance (01:07:33), we see Alberto fighting an irate Michele who wants revenge for the kidnapping of his wife by his former comrade. Michele hits Alberto, calling him a “coward” and a “traitor.” While this happens, we hear the utterances of some veterans in the background; they are speaking at a meeting for the creation of the National Popular Front, which is taking place nearby. Ironically, their speech is all about solidarity, peace, and mutual support (“no discord, no divisions between us”); yet the two fighters—particularly Michele—seem oblivious to these words. It is only when one of the veterans’ chants is heard (01:09:17) that Michele stops hitting Alberto and forgives him for his crimes, thereby enabling him to be readmitted into the community. Folk music thus acts as a cohesive agent: it provides the most effective expression of a mutually supportive community, the vehicle through which the sinner (Alberto) can be pardoned and reject his individualistic ambitions.

The fact that folk music in Caccia tragica is imbued with socialist values and poses a serious threat to those who represent capitalism is also suggested by a scene in the original script that was ultimately deleted from the final cut: [23]

Daniela is on a boat with the hostage Giovanna. While they are rowing down a river, the singing of the veterans heading towards their meeting resounds from one of the riverbanks. The scene’s physical, political, and moral space is defined through music. Daniela wants to remain in the middle of the river because the song, which threatens her individualist conception of the world, grows louder when the boatman gets closer to the banks. Folk music is perceived by the villain as a powerful and haunting presence.

From what has been said above, it is apparent that De Santis generally adheres to a straightforward binary opposition between folk and popular music, respectively, as the repositories of revolutionary/progressive values on the one hand and regressive/consumerist principles on the other. Nevertheless, certain moments in Caccia tragica complicate this rather simplistic, black-and-white divide. I have already noted how the use of “Avanti siam ribelli” in the radio scene touches on this problematic dichotomy. At other points in the film, we find folk music accompanying the emergence of reactionary values. A good example occurs at the beginning of the film. Here, the field workers are being forced by some of their despotic landowner’s henchmen to return the lands and agricultural machinery that they have been leasing; at the same time, a smaller group of peasants who have just arrived on some carriages help the henchmen to execute the landowner’s orders. The local community is thus internally divided, and the mercenaries mock the other peasants by singing the “Osterie,”—i.e., certain well-known sarcastic folk songs (00:09:22). Here, folk music becomes a divisive element rather than a tool that encourages social solidarity.

The broader idea that the folk, as a revolutionary force, is immune to and rejects hegemonic culture is questioned in certain scenes within this film as well as in others that De Santis directed. There are moments in which the peasants are shown to be enjoying the morally equivocal sounds of capitalism. The complex scene with the veterans’ train is a case in point (00:58:32). In this instance, some of the villains (Alberto and a few black market dealers) and the peasants share the same physical and sonic space, since they are both on a train where a band is playing a “boogie-woogie” (see figure 3). While the performance is a musical index of deleterious Americanism, the peasants nevertheless seem to be enjoying it. In the original script, De Santis indicated that he wanted a folk tune to be performed here, whereas in the film’s final version the voice of the peasants has been erased and replaced by American music. Of course, this might be read as the director’s critique of the risks of cultural contamination. On the other hand, this musical choice could also be interpreted as indicating the director’s penchant for hybridization, which informs at least part of the soundtrack and enables unexpected exchanges to emerge between folk culture and mass-mediated culture.

Fig. 3. De Santis, Caccia tragica. Still frame at minute 00:58:56 (see note 19).

The above examples show that different values are associated with folk music in De Santis’s Caccia tragica. Even if its connection with the positive characters generally seems to prevail, folk music can also be entrusted to negative characters that are driven by individualist interests. Moreover, members of the folk community seem at times to be allured by the sounds of consumerism. These short circuits certainly add complexity to the simplistic dichotomy “folk music vs. capitalism” (which is nevertheless at work in many scenes) and point to a broader tension that characterized postwar Italian culture at large. Indeed, the wave of folklorism that emerged in the wake of the publication of Gramsci’s “Osservazioni sul folklore” in 1950—a wave which found its immediate outlet in the aforementioned ethnographic and ethnomusicological expeditions, and culminated with the folk music revival movement in the 1960s and 1970s—was plagued with latent and unavoidable contradictions. In an article published in 1978, Diego Carpitella denounced the “false ideology” that informed the rediscovery of musical folklore. In his view, questionable paternalism and essentialism often lurked behind the revivalists’ attitude towards folk culture, depriving it of its agency. Furthermore, Carpitella noted that the call for “authenticity” by those who wanted to popularize folk music was in fact leading to a commodification of the repertoire, which was almost always decontextualized and spectacularized. Such inconsistencies in the “ideology of folklore” were the result of the impossible attempt to deny the dialectical relationship existing between the revived folk music and the (capitalist) cultural system into which it was being introduced. [24] I contend that these insightful reflections—especially the point on the dialectic between folk music and capitalism—can be fruitfully applied to the representation of folk music in De Santis’s soundtracks, for they appear to foreshadow questions that would become burning in the following decades.

The Power of the Peasants’ Soundscape: Whistles and Bells.

There are other productive ways to explore De Santis’s approach to the voice of the portrayed folkloric communities, and to address Dyer’s questions about hierarchies and sonic representation of the subalterns. One such way is to abandon a music-centered perspective and focus instead on sound effects. Elena Mosconi has claimed that neorealism was characterized by a new sensibility towards sounds and noises. Indeed, many Italian postwar films portrayed not only landscapes, but also soundscapes “that were neglected by previous cinema.” [25] These soundscapes, I would add, were invested with cultural, ideological, and political values. This is particularly true for De Santis’s films, where recurring sonic elements characterize and tend to empower the represented subaltern communities and their space. In the following pages, I shift my attention from traditional musical values to a consideration of the complex folkloric soundscape in Caccia tragica. I discuss, in particular, the crucial role played by whistles and bells. [26] While I acknowledge that these sounds belong to different fields of human expression, discussing them together enables me to show how they achieve similar communicative and political functions in Caccia tragica, and how they both provide the represented people with means to threaten the film’s villains and their values.

The act of whistling pervades a scene in Caccia tragica which follows the aforementioned “radio” episode. At 00:52:25, we see the bandits leaving their refuge, which has been discovered and put under siege by Michele and his fellow companions. Daniela, Alberto, and their accomplices make their way through the surrounding crowd by using Giovanna, their hostage, as a human shield. However, their escape is soon transformed into a walk of shame. One of the peasants starts whistling, and the gesture is repeated by his companions (see figure 4). A choir of whistles subsequently accompanies the bandits. Daniela is the only one who shows indifference, while Alberto looks nervous and frightened. Whistling simultaneously empowers the peasants whilst also weakening the bandits.

Fig. 4. De Santis, Caccia tragica. Still frame at minute 00:53:33 (see note 19).

Whistling is a sonic signifier of peasants and proletarians in many Italian films. [27] A systematic examination of the role of whistling in narrative cinema is long overdue. Here I will limit myself to a few general observations. Whistling is often connected with ideas of difference and excess. In fact, with its potential noisiness and its distance from verbal language, whistling occupies a disreputable position. People have always whistled, but this sonic act inhabits the fringes of official culture, as testified by the difficulty of finding studies that explore its history, and by the rarity, in the musical realm, of professional whistlers. [28] Whistling is often associated with the lowest classes and their supposedly rude behavior. It is not surprising, then, that well-mannered bourgeois rarely whistles in Italian postwar films; this act is generally associated with people living on the edge of society, in particular peasants, miners, rascals, proletarians, and protesters. Whistling implies the violent emission of high-pitched sounds, which defy the rationale, measured logic of verbal discourse, the dominant norm of logos. A good way of thinking about whistling—or at least some forms of whistling, which can be heard and seen in Italian films portraying folk communities—is by drawing a parallel with Nadia Seremetakis’s definition of “the screaming” ( klama) in her ethnography of women’s mourning practices in Inner Mani, Greece. Seremetakis understands screaming in women’s laments as a bodily, excessive acoustic utterance that, for its violence and distance from the hegemonic acoustics based on low voices and “rational” sounds related with language, retains a certain degree of “transgression.” She argues that Inner Mani women “disseminate the signs of transgression through screaming. Screaming is tied to the condition of anastatosi, disorder and inversion.” [29] For its excess, screaming participates in “dangerous” and “contagious” threatening attitudes against dominant powers, and it “demarcates and encloses a collectivity of subjects in exile.” [30]

In a similar vein, we can read whistling as a marker of cultural, social, and political difference, which may be why Italian directors frequently link it with folkloric or peripheral worlds that are believed to resist the hegemonic realm. As with klama, the excessive, abnormal whistling can represent a threatening and transgressive sound. This emerges with clarity if we go back to the aforementioned scene in Caccia tragica. While the peasants are holding rifles, they cannot use these against the villains because a gunfight would potentially harm Giovanna, the hostage. Whistling, then, offers an alternative form of resistance. One of the peasants starts whistling and is immediately followed by the others as a sort of vocal ensemble that submerges the bandits—an effect that is visually reinforced by the dolly shot of the whistling people, and the shot/countershot showing the reaction of the villains. The idea of a threatening choral sound that stems from the initiative of an individual is a strong metaphor of solidarity, and the crescendo effect that is obtained through this process of sonic accumulation is a particularly effective way to show the overwhelming power of the folk’s whistling. [31]

The sound of bells, like whistling, is another index of the folkloric space. In Caccia tragica, bell sounds provide an additional way of symbolizing the peasants’ power. [32] If one thinks of the historical significance of bells in rural communities, this comes as no surprise. In his seminal study Village Bells, Alain Corbin discusses several values with which bells have been connected throughout different periods of European history, and he shows how they have been fundamental in shaping social time and space (one that is physical, spiritual, and political). Indeed, before the advent of industrialization, bells were one of the most important sounds, and although their centrality and power declined with the onset of metropolitan soundscapes, they nonetheless retained a certain degree of relevance in the “peripheries” (i.e., towns and rural villages), hence their connection with the folkloric soundscape. [33] Steven Feld, who has also devoted himself to studying and recording bells, has reflected on how they can “signal both authority and disruption”—that is, they are invested with power in certain historical and social contexts. [34]

Caccia tragica is only one of many Italian films in which bells are used to define the folkloric world. [35] What is interesting, here, is that the peasants’ bells exhibit a powerful agency of their own, an acoustical force that stands in opposition to the capitalist world. They can be heard at many points in the film, notably when the peasants ring them to mobilize the whole community in chasing the bandits (00:29:02: “Sound the alarm with town bells, too!”). Beyond this narrative circumstance, however, it is the quasi-expressionist treatment of their sound which makes them such a powerful signifier of the peasants’ antagonism. By using this acoustic device, De Santis tends to blur the lines between the diegetic and the non-diegetic, and to play with our sense of space: indeed, in many scenes, the villains’ voices are drowned out by loud bell ringing, which seems to come from nowhere. For example, the bandits’ refuge is clearly located in an isolated area, and yet bells invade and pervade this space, often disrupting the communication between the villains in a way that reinforces the idea of folk as representing a haunting, controlling presence. At 00:39:40, Daniela is shown entering a room to meet some of her accomplices. When she opens the door, the bells suddenly fill the air. The unnaturalness of the sync-point somehow empowers their sound by making it seem abnormal, strange, and unexpectedly spectral. Later in this scene (00:45:40), Daniela enters another room: the bells, which had stopped ringing, now invade her space once again. One of the accomplices hears them and makes an ironic comment about the peasants’ uprising (00:45:53); Daniela will do the same while talking to Alberto only a couple of minutes later in the film (00:47:47). This seems to contradict the idea that the bells occupy a non-diegetic space, but the sync-points prepared by De Santis and the anomalous volume create an expressionistic effect of estrangement that would not be possible without the ambiguous blending of the diegetic and the non-diegetic. Elsewhere (00:32:26–00:33:11) De Santis opts for more traditional sonic bridges: different scenes and spaces in the film are connected through the bells’ sound—something which gives the impression that the bells (and by extension the peasants and their voices) are everywhere.

Sounds on Paper: Noi che facciamo crescere il grano

Before concluding, it is worth devoting a few words to an unfinished film project which De Santis conceived in relation to theTrilogy of the Land. The script for the film in question, entitled Noi che facciamo crescere il grano (We Who Grow Grain), is kept at the CSC archive, and it was written in the 1950s by the director himself, in collaboration with Corrado Alvaro and Basilio Franchina. The aim of the authors was to narrate the precarious conditions of farm laborers in Calabria in the years following the Second World War, where latifundism, unemployment, and poverty were long-standing problems. Drawing on real events that took place in Corvino, near Crotone, the film aimed to focus on peasant resistance against the exploitative system enjoyed by the landowners. Folk music and sounds would have played a crucial role in relaying this conflict and in conveying the film’s progressive message.

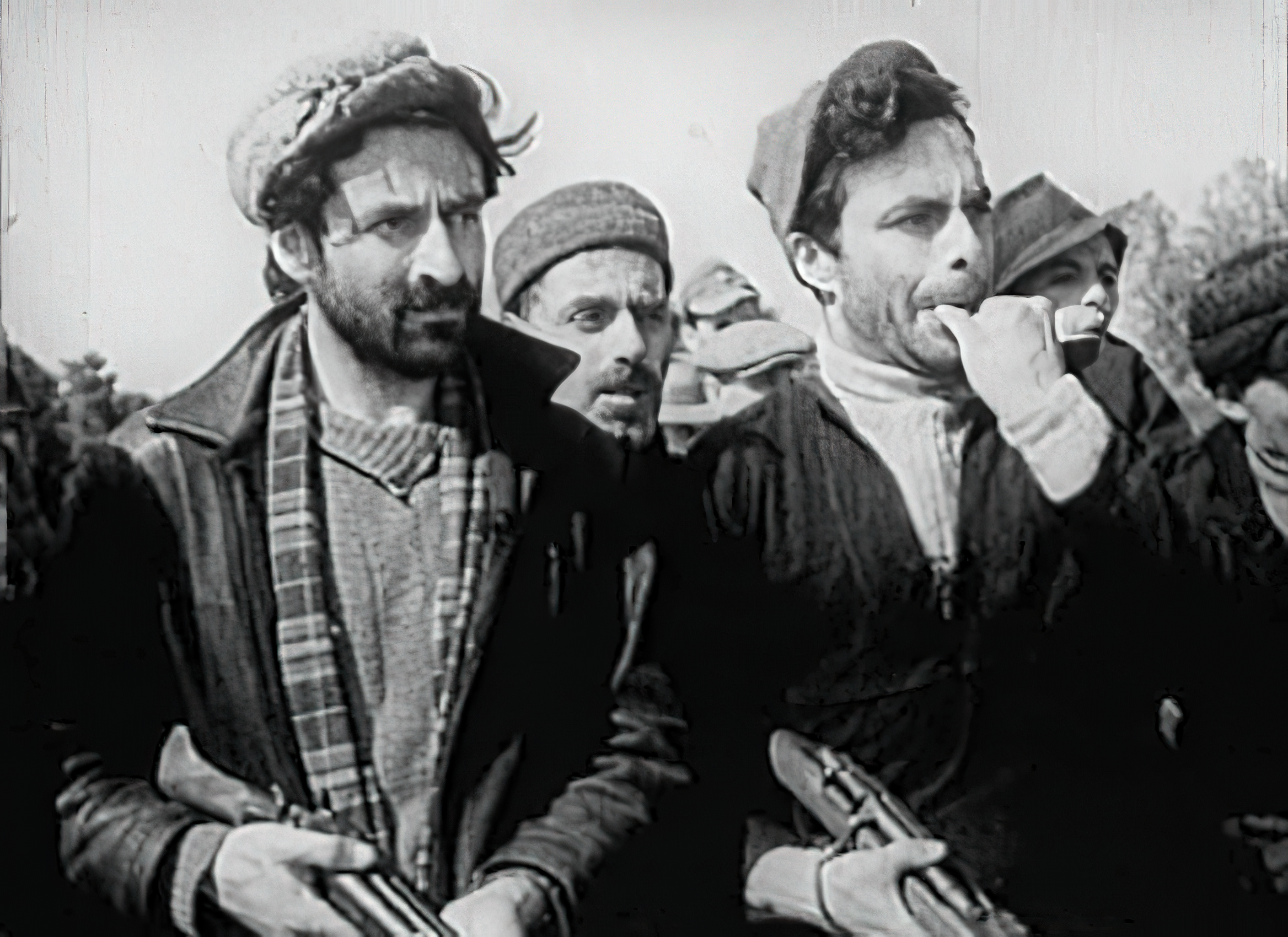

The film’s main protagonists are Annibale Zappalà and his family. With the aid of the town’s schoolteacher, who somehow epitomizes the Gramscian “organic intellectual,” Annibale tries to obtain the usufruct of the fief of San Donato—an area of uncultivated land which figures among the territories managed by the authoritarian Don Carmelo Zampa on behalf of the latifundist Baron Balsamo—from the Crotone authorities. Annibale convinces the community to rebel against Don Carmelo and sign a petition to obtain the fief, to which the peasants had legal rights. This consequently triggers a violent conflict between the peasant community and Don Carmelo. Arrested by corrupt policemen, Annibale is then released; he subsequently goes on to lead a peasant revolt which culminates in their reclaiming of these lands, Don Carmelo’s defeat, and ultimately Annibale’s death, through which he becomes a sort of martyr.

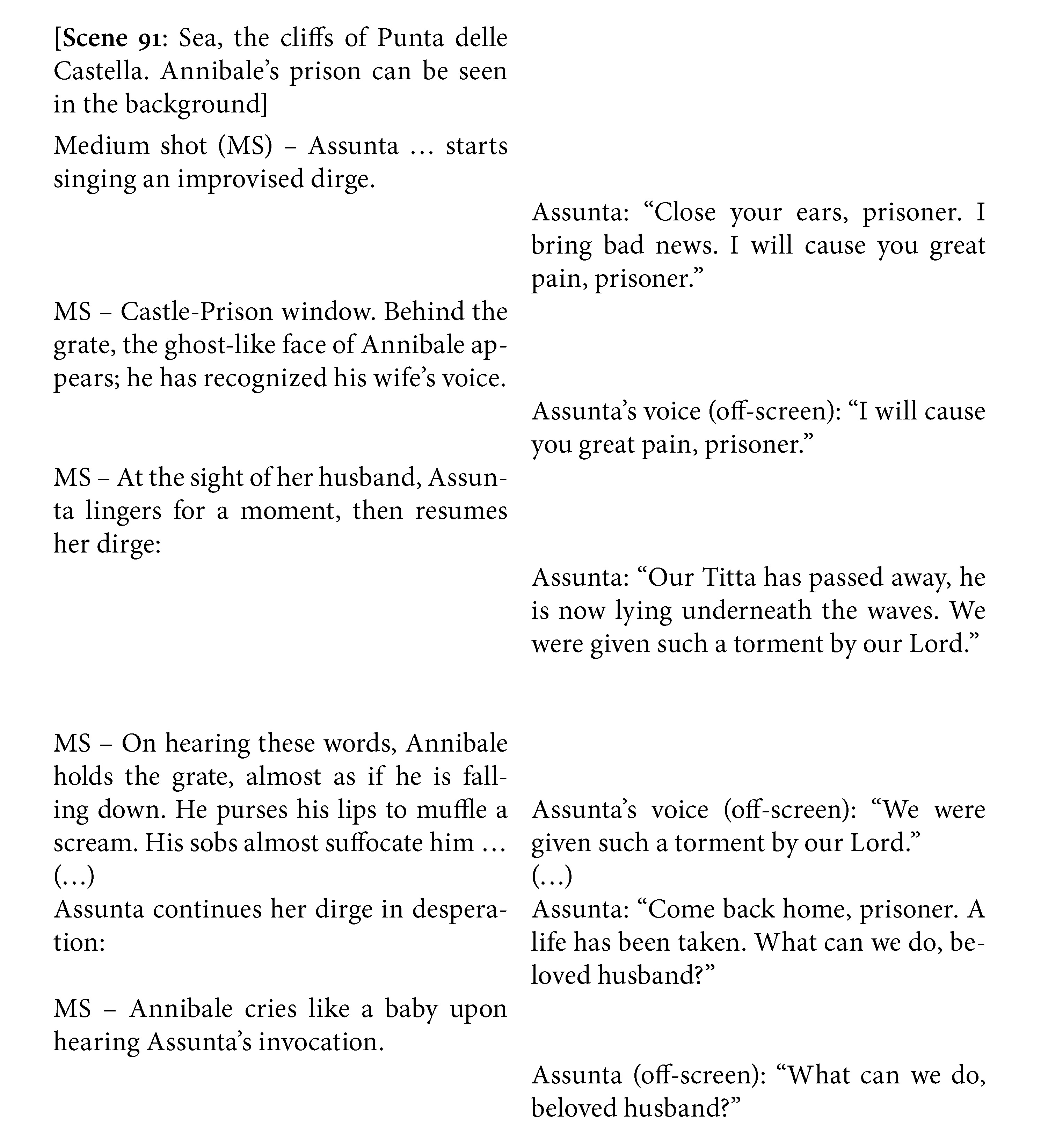

Since the project was never completed, it is impossible to ascertain whether De Santis planned to accompany this film with an orchestral score, as he had done in his previous productions. Nevertheless, the script’s draft provides an insight into the role that sound and musica popolare would have played in the film. Apart from decorative, atmospheric moments where folk music would have primarily added a touch of local color to the events portrayed, there are several other scenes in which this repertoire fulfills a crucial dramatic and ideological role. [36] A notable example occurs halfway through the film. After his initial attempts to occupy the lands and return them to the peasant community, Annibale is arrested and imprisoned in La Castella, a fortress built on a small island. Tragic events follow: a landslide hits the village of Corvino and causes the death of Titta, one of Annibale’s sons. Out of despair, Assunta secretly goes to the prison where her husband is confined and breaks the terrible news to him. In order to circumvent the jailers’ control, she improvises a dirge beneath the fortress’ walls.

Assunta performs her funeral lament from a boat, just below the cliff where Annibale’s prison is located, and her song conceals the act of informative and emotional exchange that is happening between the pair. Folk music thereby serves as a powerful way to transgress the oppressors’ control. A similar thing happens in Riso amaro, where one of the mondine (rice weeders) explains to one of the protagonists, Francesca, that “they [the landowners] don’t let us talk; if you have anything to say, sing it.” [37] An even more striking connection with Noi che facciamo can be found in Vittorio De Sica’s Ieri, oggi, domani ( Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, 1963). [38] In the film’s first episode (Adelina, set in Naples), the protagonist (a cigarette smuggler) is put in jail. One night, her husband Carmine manages to reach the prison walls where he begins to sing a serenade under her window. Carmine’s song provides a means to bypass the guard’s control and inform Adelina of the mercy petition that has just been submitted. As this example reveals, the trope of using folk music to express subversive power seemingly had a long life in Italian film.

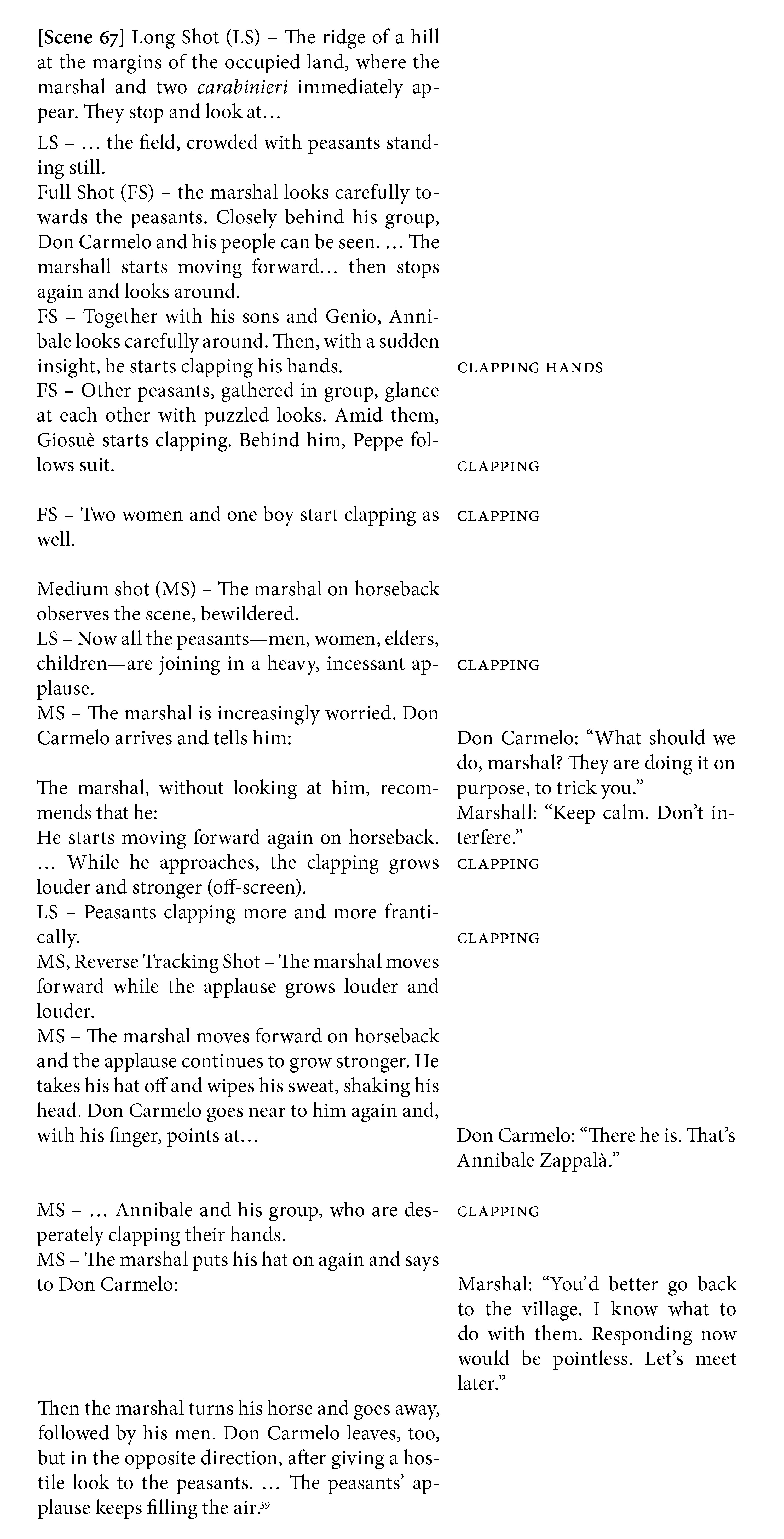

But, once again, it is especially through sound that De Santis seeks to empower the folk’s voice. Even in the case of Noi che facciamo, the folkloric soundscape is not composed exclusively of songs, for it also includes numerous non-verbal signals that seeks to undermine the capitalist oppressors’ order. The first attempt by Don Carmelo and the police to disband the peasants fails. In this instance, the weapon used by the community against their enemies is the sound of clapping. This scene thus invites comparison with the one discussed earlier in Caccia tragica that makes use of whistling. In both cases, whistles and clapping are used in a crescendo that goes from individual to group performance, and from low volume to high.

Steven Connor has provided an insightful ethnography of clapping, noting how the principle of “adversity”—an impact of things, namely hands—is a precondition of this gesture. As he explains, “clapping retains its associations with violence, functioning as an emblematic display on the body of the aggressor of what may be in the offing for his victim.” [40] Of course, this violent, oppositional understanding of clapping is just one of many possible cultural interpretations of this gesture. Connor acknowledges, for example, that clapping can also be linked to magical actions, therapy, and celebration, among other things. Yet this reading fits perfectly with the situation relayed by the script of Noi che facciamo. What is more, Connor highlights how clapping “makes you aware of yourself” and facilitates a “circulation of energies” between the clapping subjects, which is precisely the same kind of empowerment that De Santis’s peasants seem to experience. [41]

The last fight between the peasants and the landowners is also accompanied by a complex audiovisual dramaturgy—one that is not dissimilar from the strategies that De Santis had already employed in Caccia tragica, with its alternation of villain and peasant sounds. Here, the opposition is between a sowers’ song initiated by Annibale and imitated by all the peasants, and the sound of the trotting horses of Don Carmelo’s henchmen.

This scene occurs immediately before the end of the film. The land has been reoccupied by the peasants following the authorization on behalf of the Crotone committee. Yet Don Carmelo refuses to capitulate and sends instead three horsemen to kill Annibale and convince the peasants to vacate the property. While Don Carmelo’s plan ultimately fails, Annibale does indeed get killed, in a portrayal of the villain’s last atrocity before the final triumph of the community of peasants. The conflicting groups are sonically characterized by the opposition between the sewers’ song, which becomes a threatening weapon that invades the villains’ space through a few sound bridges, and the trotting horses, whose noise periodically emerges and occasionally drowns out the other sounds. The juxtaposition of these two auditory elements creates the necessary counterpoint to enhance the underlying tension of this climactic scene. In keeping with the socialist ideal, we witness a shift from the individual singer to the singing community, and from a fleeting solo voice to the full-bodied chant of a whole group, magnified by the choral reprise of Annibale’s song after his death, at the end of the planned film.

In the script of Noi che facciamo crescere il grano, folk music functions as a repository of anti-capitalist values, a socially-binding agent that inspires the peasants to rebel against the oppressors and their individualistic mentality. The discourse on folk music that emerges from this film, then, seemingly fits in well with the “folk culture vs. capitalism” dichotomy outlined by many leftist intellectuals and folk music rediscoverers at around the same time. Such a dichotomy became even more marked during the 1960s, when the use of folk music became increasingly political, the surrounding debates displaying an obsessive concern about its alleged separation from consumerist, bourgeois society. De Santis’s films are prescient in that they anticipate the tenor of these debates whilst also offering a complex picture of their subject. In Caccia tragica the border between folk and capitalist culture is sometimes blurred. Admittedly, short-circuits in this discursive divide are quite exceptional in De Santis, but such exceptions are of particular interest, not least because they highlight ongoing tensions in Italian society that cannot be addressed by black-and-white narratives that enshrine folk music as an antidote to capitalist culture. The seeming contradictions in De Santis’s soundtracks show that a simplistic view of folk music (i.e., as repository of anti-capitalist values) in fact belies a more complex, dialectic reality. Hence the importance of studying the representation of folk music in neorealist films, in spite of (or maybe because of) Dyer’s observation that their soundtracks were inconsistent with the aims of this kind of cinema.

The case of De Santis’s films also shows that the claim about neorealism as being indifferent to the voices of subaltern groups is not entirely accurate. A study of the soundscapes constructed by De Santis in his rural films gives a vivid impression of the director’s attempt to empower—literally and metaphorically—the voice of the folk (albeit through the inevitably artificial means and conventions of narrative cinema). The “resonance” given to bells, whistles, and clapping in Caccia tragica and Noi che facciamo endows the peasants with a strong, haunting sonic presence that poses a serious, tangible threat to their enemies. In this respect, the sonic strategies adopted by De Santis to characterize his protagonists appear to be less ambiguous and more robust than his musical choices. Mapping the folkloric soundscapes in other films by De Santis and his contemporaries is the next step of a research—to my mind long overdue—aimed at exploring in a nuanced fashion the modus operandi and cultural politics that underpin the construction of subaltern voices in postwar Italian cinema.

****

Transcriptions of the original scripts in the Fondo Giuseppe De Santis, Biblioteca Luigi Chiarini, Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, Rome.

Doc. 1: Excerpt from Caccia tragica. Sezione Sceneggiature, Sceneggiatura 1946–1947, SCENEG 00 09691. 292 unbound pages, A4; typescript with autograph annotations.

Doc. 2: Excerpt from Noi che facciamo crescere il grano. Sezione Sceneggiature, Sceneggiatura 1949, SCENEG 00 09686. Bound volume, A4; typescript with autograph corrections.

Doc. 3: Excerpt from Noi che facciamo crescere il grano.

Doc. 4: Excerpts from Noi che facciamo crescere il grano.

* I want to express my gratitude to the staff of the Biblioteca Chiarini at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia (Rome), who allowed me to study the archival documents kept at the Fondo Giuseppe De Santis. All translations from Italian (including the original scripts from the director’s archive) are mine, unless otherwise indicated.

[1] Cesare Zavattini, “Some Ideas on the Cinema,” Sight and Sound 23, no. 2 (1953): 64–69; originally published as “Alcune idee sul cinema,” Rivista del cinema italiano 1, no. 2 (1952): 5–19. For an overview of the history and theory of neorealism, see: Mark Shiel, Italian Neorealism: Rebuilding the Cinematic City (London: Wallflower Press, 2006); Gian Piero Brunetta, Il cinema neorealista italiano: storia economica, politica e culturale (Bari: Laterza, 2009); Torunn Haaland, Italian Neorealist Cinema (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012).

[2] Antonella Sisto, Film Sound in Italy: Listening to the Screen (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2014), 83. In the fourth chapter of her book (“The Soundtrack after Fascism: The Neorealist Play Without Sound”) Sisto links the “lack of audiophilia” with neorealism’s passive acceptance of dubbing practices deriving from Fascist cinema, and with the directors’ resistance against technologies of direct sound recording. However, this does not necessarily mean that neorealist filmmakers had no interest in sound as such, nor that their fabricated soundtracks played ancillary roles. The case of De Santis’s rural films explored in this article demonstrates quite the opposite.

[3] Richard Dyer, “Music, People and Reality: The Case of Italian Neo-Realism,” in European Film Music, ed. Miguel Mera and David Burnand (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006), 28–40: 28.

[4] Dyer, “Music, People and Reality,” 28. See also: Sergio Bassetti, “Continuità e innovazione nella musica per il cinema,” in Storia del cinema italiano, vol. 8, 1949–1953, ed. Luciano De Giusti (Venice: Marsilio, 2003), 325–35.

[5] Dyer mentions De Santis’s films in his article and devotes part of his discussion to Riso amaro. However, his method and questions are partly dissimilar from mine, as I shall clarify in the following pages.

[6] A copy of the thirteen-page project of Canti e danze and a letter attesting Goffredo Lombardo’s feedback on the film proposal are held at the director’s archive (Giuseppe De Santis, “ Canti e danze popolari in Italia,” SCENEG 00 09796, Sceneggiature Soggetto 1950–1960, Fondo Giuseppe De Santis, Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, Rome). For a transcription of Canti e danze (without the related correspondence with Lombardo), see Antonio Vitti, ed., Peppe De Santis secondo se stesso: conferenze, conversazioni e sogni nel cassetto di uno scomodo regista di campagna (Pesaro: Metauro, 2006), 491–95.

[7] On the organization of the expedition, and the development of ethnomusicology in postwar Italy, see: Diego Carpitella, ed., L’etnomusicologia in Italia: primo convegno sugli studi etnomusicologici in Italia (Palermo: Flaccovio, 1975); Alan Lomax, L’anno più felice della mia vita: un viaggio in Italia 1954–1955 , ed. Goffredo Plastino (Milan: Il saggiatore, 2008); Francesco Giannattasio, “Etnomusicologia, ‘musica popolare’ e folk revival in Italia: il futuro non è più quello di una volta,” AAA – TAC 8 (2011): 65–85; Maurizio Agamennone, ed., Musica e tradizione orale nel Salento: le registrazioni di Alan Lomax e Diego Carpitella (agosto 1954) (Rome: Squilibri, 2017). On the figure of Ernesto De Martino, his work and his collaboration with Diego Carpitella, see: Ernesto De Martino, Morte e pianto rituale nel mondo antico. Dal lamento funebre antico al pianto di Maria , ed. Marcello Massenzio (Turin: Einaudi, 2021; 1st ed. 1958); De Martino, La terra del rimorso. Contributo a una storia religiosa del Sud (Milan: Il saggiatore, 2020; 1st ed. 1961); Diego Carpitella, “L’esperienza di ricerca con Ernesto De Martino,” in Conversazioni sulla musica (1955–1990): lezioni, conferenze, trasmissioni radiofoniche (Florence: Ponte alle Grazie, 1992), 26–34; George R. Saunders, “‘Critical Ethnocentrism’ and the Ethnology of Ernesto De Martino,” American Anthropologist 95, no. 4 (1993): 875–93; Maurizio Agamennone, ed., Musiche tradizionali del Salento: le registrazioni di Diego Carpitella ed Ernesto de Martino (1959, 1960) (Rome: Squilibri, 2008); Giorgio Adamo, ed., Musiche tradizionali in Basilicata: le registrazioni di Diego Carpitella ed Ernesto De Martino (Rome: Squilibri, 2012).

[8] I fully agree with Michel Chion’s notion of “audio-vision,” which implies a re-evaluation of the intertwined nature of all the components of audiovisual media. See Michel Chion, Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen, 2nd ed., trans. Claudia Gorbman (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019). In this article I attempt to show parallelisms and contrasts between sound, montage, and framing in film, for these elements complement each other and all are fundamental for the emergence of discourses on folklore.

[9] Maurizio Corbella, “Which People’s Music? Witnessing the Popular in the Musicscape of Giuseppe De Santis’s Riso amaro (1949, Bitter Rice),” in Music, Collective Memory, Trauma, and Nostalgia in European Cinema After the Second World War , ed. Michael Baumgartner and Ewelina Boczkowska (New York: Routledge, 2020), 45–69: 47. See also Francesco Pitassio, “Popular Tradition, American Madness and Some Opera: Music and Songs in Italian Neo-Realist Cinema,” Cinéma & Cie 11, nos. 16/17 (2011): 141–46.

[10] For reasons of space, this paper does not take into account Riso amaro and Non c’è pace tra gli ulivi. Nevertheless, it is my intention to devote a future article to the discussion of folk music, sound, and audiovisual strategies in these films (particularly on the less-studied Non c’è pace ), which will enable me to expand on some of the points examined here.

[11] For an overview of De Santis’s cinema, see: Antonio Vitti, Giuseppe De Santis and Postwar Italian Cinema (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996); Marco Grossi, ed., Giuseppe De Santis: la trasfigurazione della realtà / The Transfiguration of Reality (Rome: Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, 2007).

[12] Pepa Sparti, ed., Cinema e mondo contadino: due esperienze a confronto: Italia e Francia (Venice: Marsilio, 1982); Michele Guerra, Gli ultimi fuochi: cinema italiano e mondo contadino dal fascismo agli anni Settanta (Rome: Bulzoni, 2010).

[13] Antonio Gramsci, “Observations on Folklore,” in The Antonio Gramsci Reader: Selected Writings, 1916–1935, ed. David Forgacs (New York: New York University Press, 2000), 360.

[14] Gramsci, “Concept of ‘National-Popular’,” in The Gramsci Reader, 368.

[15] On this topic, see: Vitti, Peppe De Santis secondo se stesso, 189, 231 and 235. Revealing of some connections between De Santis and Gramsci’s thought are also the director’s reflections in “Cinema e Narrativa,” Film d’oggi 1, no. 21 (1945): 3.

[16] See Joseph Luzzi, A Cinema of Poetry: Aesthetics of the Italian Art Film (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014).

[17] The translated passage is quoted in Corbella, “Which People’s Music?”, 48.

[18] One point that triggered harsh criticism and that appears to have been a source of anxiety for De Santis himself is the director’s ambivalent attitude towards American culture. De Santis was strongly influenced by American film, but at the same time he criticized American capitalism and its articulation through mass-media; see Peter Bondanella, Italian Cinema: From Neorealism to the Present (New York: Ungar, 1983), 82-85. De Santis never denied his admiration for the literature of the New Deal era, which he considered one of neorealism’s sources of inspiration, and for American Western and Musical films. Nevertheless, De Santis’s reactions to interviewers’ and critics’ comments sometimes betrayed an anxious need to establish some distance between his cinema and the American models. In an exchange with Antonio Vitti, for instance, he bypassed this intuitive remark of the interviewer: “I’ve always wondered why you feel bothered when critics notice elements in your films coming from American Westerns” (see Peppe De Santis secondo se stesso, 189; see also, in the same volume, Vitti’s interviews with De Santis at pages 61, 66 and 170–73, and Vitti’s article “L’influenza della letteratura americana sul neorealismo”, 21–36). Moreover, while De Santis declared on several occasions his respect for American democracy, he also took a stance against the consumerist side of American culture, symbolized by “boogie-woogie, chewing gum, easy money”—elements that are nevertheless extremely seductive in his films; quoted in Francesco Pitassio, Neorealist Film Culture, 1945–1954. Rome, Open Cinema (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019), 40. On the ambiguous cultural politics and ideologies that informed postwar Italian leftist circles, see Stephen Gundle, Between Hollywood and Moscow: The Italian Communists and the Challenge of Mass Culture , 1943–1991 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000).

[19] I refer here to the streaming file available online: “Caccia tragica (Giuseppe de Santis) 1947,” YouTube, uploaded on October 12, 2021. The film has never been distributed on DVD, but, to my knowledge, some VHS copies were released in the 1990s by Gruppo Editoriale Bramante – Pantmedia, Mondadori Video and VideoClub Luce – VideoRai.

[20] “Raccontare e spiegare, attraverso la sola musica, la situazione in cui versava l’Italia di allora,” “un’invadenza americana a livello di cultura di massa che ha sostituito sia la retorica fascista sia la genuinità popolaresca.” Guido Michelone, “Dal boogie al neorealismo: musiche e colonna sonora in Caccia tragica,” in Caccia tragica: un inizio strepitoso, ed. Marco Grossi and Virginio Palazzo (Fondi: Quaderni dell’Associazione Giuseppe De Santis, 2000), 29.

[21] See Corbella, “Which People's Music?”, 58.

[22] In the film, these connections are indirectly reinforced by the fact that “Lili Marleen” is heard immediately after the end of “Avanti siam ribelli”.

[23] “Caccia tragica – Sul fiume c’è ancora la guerra ,” SCENEG 00 09691, Sceneggiature 1946–1947, Fondo Giuseppe De Santis, Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, Rome. De Santis erased a few sentences in the original script, as reflected in my transcription (see Appendix, document 1).

[24] See Diego Carpitella, “Le false ideologie sul folklore musicale,” in Diego Carpitella, Gino Castaldo, Giaime Pintor et al., La musica in Italia: l’ideologia, la cultura, le vicende del jazz, del rock, del pop, della canzonetta, della musica popolare dal dopoguerra ad oggi (Rome: Savelli, 1978), 207–39; Diego Carpitella, “Etnomusicologica. Considerazioni sul folk-revival”, in Conversazioni sulla musica, 52-64. See also: Goffredo Plastino, “Introduzione” and Marcello Sorce Keller, “Piccola filosofia del revival”, in La musica folk: storie, protagonisti e documenti del revival in Italia , ed. Goffredo Plastino (Milan: Il Saggiatore, 2016).

[25] Elena Mosconi, “Per un paesaggio (sonoro) italiano: ri-ascoltare il neorealismo,” in Invenzioni dal vero: discorsi sul neorealismo, ed. Michele Guerra (Parma: Diabasis, 2015), 239–54: 246.

[26] In this article I must limit my discussion to Caccia tragica, but other Italian postwar films feature whistles and bells as distinctive elements of rural/folkloric soundscapes. Some examples are mentioned in notes 27, 32, and 35.

[27] Like Caccia tragica, some films use the subalterns’ whistles in a non-musical way. This is the case of the whistling boys in the last scene of Roma città aperta (dir. Roberto Rossellini, 1945): the noisy sound they produce can be intended as an expression of solidarity to Don Pietro and protest against his execution. In many other Italian films—especially from the 1960s and the 1970s—whistles acquire musical value; nevertheless, they are almost always associated with folkloric, rural, and exotic contexts—i.e., with ideas of spatial and cultural otherness. Pier Paolo Pasolini’s films abound in scenes where the “sub-proletarian” protagonists whistle folk tunes (e.g., Ninetto Davoli in Decameron, 1971, and Canterbury Tales, 1972). Other films adopt the whistle as an element of the extradiegetic score: particularly famous are the whistles of Alessandro Alessandroni that resonate in the music by Ennio Morricone for Lina Wertmüller’s I basilischi (1963) or for Sergio Leone’s western films.

[28] There is scant literature on whistling. The most recent and comprehensive study is A Brief History of Whistling, by John Lucas and Allan Chatburn (Nottingham: Five Leaves Publications, 2013). See also: Peter F. Ostwald, “When People Whistle,” Language & Speech 2, no. 3 (1959): 137–45; A.V. van Stekelenburg, “Whistling in Antiquity,” Akroterion 45 (2000): 65–74. The reflections by Steven Connor in Beyond Words: Sobs, Hums, Stutters and other Vocalizations (London: Reaktion Books, 2014) might also prove useful to make sense of the act of whistling and its communicative values. Connor focuses on “the world of sound events beyond articulate speech” (10); whistling does not feature in his analysis, but Connor’s idea that “the [non-articulated, non-verbal] noises of the voice” (10) can have semantic, political, and cultural values might be productively applied to an ethnography or a history of whistling (both in cinema and beyond).

[29] Nadia Seremetakis, The Last Word: Women, Death, and Divination in Inner Mani (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), 72.

[30] Seremetakis, The Last Word, 101.

[31] The use of sonic crescendos associated with the folkloric world will become a trope in De Santis’s films (for instance, in Riso amaro and Non c’è pace tra gli ulivi) and was also employed by other postwar Italian directors (e.g., Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Seta), a topic I will discuss in another article.

[32] In “Per un paesaggio (sonoro) italiano,” Mosconi examines the presence and role of bells in various neorealist films. As an example of bells used by peasant communities to resist the oppressors, she mentions the case of Vivere in pace ( To Live in Peace, 1947, dir. Luigi Zampa). Mosconi’s article does not provide close readings but proves a stimulating starting point for further analyses.

[33] Alain Corbin, Village Bells: Sound and Meaning in the 19th-Century French Countryside , trans. Martin Thom (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998). See also: Luc Rombouts, Singing Bronze: A History of Carillon Music (Leuven: Lipsius Leuven, 2014).

[34] Steve Feld and Donald Brenneis, “Doing Anthropology in Sound,” American Ethnologist 31, no. 4 (2004): 469.

[35] See, for instance, the opening of Luchino Visconti’s La terra trema (1948) and Cecilia Mangini’s Stendalì (1960).

[36] The first scenes are full of references to “joyful” folk songs and instrumental pieces for mouth harp and accordion, which help construct the idea of a folkloric environment. See, for instance, scene 2: “nell’aria il suono sottile e struggente di uno scacciapensieri” (in the air, the thin, heartbreaking sound of a mouth harp); “[Paolo, one of Zappala’s sons] suonando allegramente il suo scacciapensieri” (cheerfully playing his mouth harp); scene 3: “ogni tanto una fisarmonica fa sentire la sua stanca musica” (every now and then, you could hear some weary music coming out of an accordion); scene 5: “[Paolo] canticchia allegramente” (sings merrily); see “Noi che facciamo crescere il grano,” SCENEG 00 09686, Sceneggiature 1949, Fondo Giuseppe De Santis, Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, Rome (see Appendix, document 2).

[37] See Corbella, “Which People’s Music?,” 52–56.

[38] For a comprehensive overview of this film, see Gualtiero De Santi and Manuel De Sica, eds., “ Ieri, oggi, domani” di Vittorio De Sica: testimonianze, interventi, sceneggiatura (Rome: Associazione Amici di Vittorio De Sica, 2002).

[39] See Appendix, document 3.

[40] Steven Connor, “The Help of Your Good Hands: Reports on Clapping,” in The Auditory Culture Reader, ed. Michael Bull and Les Back (Oxford, New York: Berg, 2003), 68.

[41] Connor, 72–73.

[42] See Appendix, document 4.