Under the International Health Regulations, or IHR (2005), all Member States must develop core capacities to detect, assess, report and respond to acute public health events and emergencies.1 For countries in the World Health Organization (WHO) South-East Asia and Western Pacific regions, the Asia Pacific Strategy for Emerging Diseases and Public Health Emergencies (APSED III) has served as the regional framework for action to guide Member States to advance the implementation of the IHR (2005) for health security.2

APSED III proposes incorporating health-care workers in the surveillance system as a priority for the early detection of public health threats. Lessons learnt from previous public health emergencies have highlighted the potential benefits of engaging health-care workers in the event-based surveillance (EBS) system for the rapid and timely detection of emerging diseases and public health emergencies.3–6 APSED III further emphasizes using multiple sources of information, including event reporting from health-care facilities and laboratories during risk assessment to better inform decision-making.2

In Viet Nam, the initial EBS system relied on media monitoring, and there was no systematic approach to promote timely reporting of public health events from health-care workers.7 In view of this, there have been plans to expand the EBS system in Viet Nam.

Viet Nam has a well-established notifiable disease surveillance and reporting system that is known, accepted and implemented by all levels of the health-care system – national, regional, provincial, district and commune levels. The reporting role relies on the curative (medicine) sector, which includes hospitals and other health-care facilities (both public and private), to report directly through an electronic reporting system and in coordination with the preventive medicine sector in their respective level – General Department of Preventive Medicine (GDPM) at the national level, Pasteur Institute or Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology at the regional level, Provincial Preventive Medicine Centre (PPMC) or Provincial Centre of Disease Control (PCDC) at the provincial level, District Health/Preventive Medicine Centre (DPMC) at the district level, and Commune Health Station (CHS) at the commune level. While the curative sector is in charge of reporting disease and events, the preventive medicine sector is responsible for verification, investigation and response in oordination with the curative sector and other relevant stakeholders.

In this study, our overall goal was to gain insights into the current situation of event reporting from the curative sector and response from the preventive medicine sector, to inform broader system strengthening and to further engage health-care workers in the surveillance of public health threats. More specifically, we aimed to identify potential facilitators and barriers for signal detection, timely reporting and rapid response in the event of a public health emergency, which we hope to eventually use as the foundation to design a hospital EBS (HEBS) system in Viet Nam.

METHODS

Study design

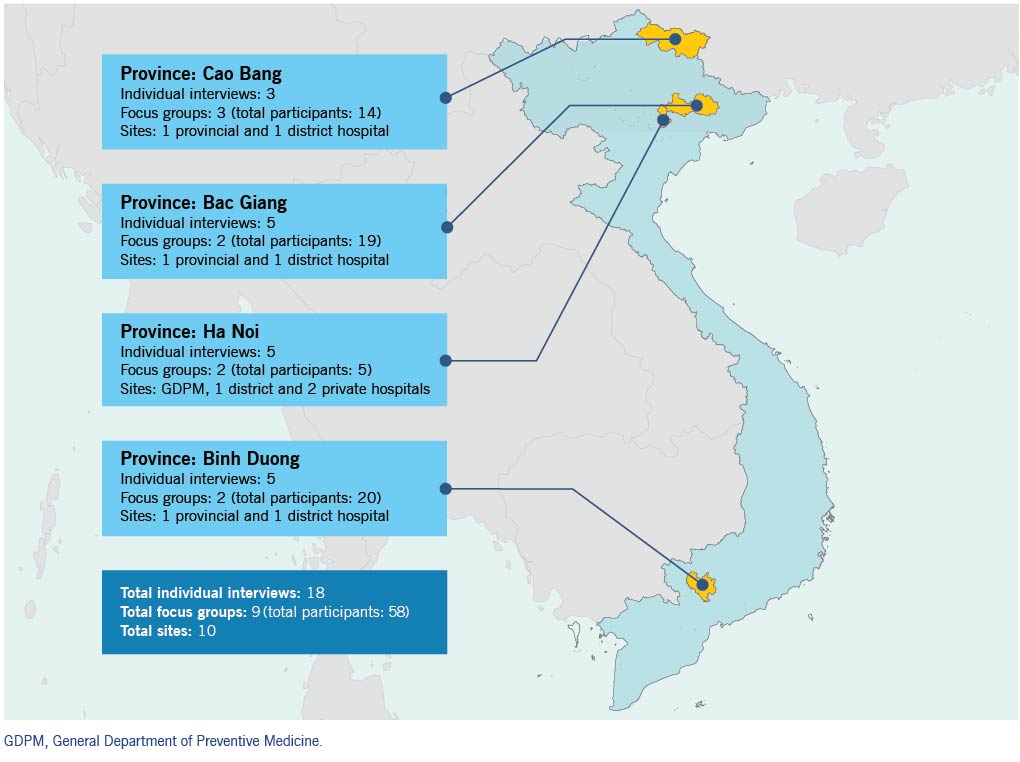

From July to December 2016, we conducted semistructured individual interviews and focus group discussions with representatives from the curative and preventive medicine sectors to explore and understand the reporting of “unusual events” from the curative to the preventive medicine sector. We also reviewed documents and archival records as supplemental data. We employed a purposeful sampling strategy for the effective use of resources to allow data extraction from “information-rich cases” to yield “insights and in-depth understanding rather than empirical generalizations” as described by Patton in 2002.8 We carried out this study in four provinces: Ha Noi (capital of Viet Nam), Bac Giang (northern Viet Nam), Cao Bang ( mountainous, remote area) and Binh Duong (southern Viet Nam) (Fig. 1). One district was purposively selected for each province to conduct the study based on convenience, their level of cooperation, having had a recent disease outbreak or has the potential to have disease outbreaks.

Fig 1. Participating sites in the qualitative study to identify facilitators and barriers for event reporting from hospitals to the public health system, Viet Nam, 2016

Participant characteristics

We conducted a total of 18 semi-structured, in-depth individual interviews and nine focus group discussions (with a total of 58 participants) (Fig. 1). Participants recruited in this study included hospital ward and laboratory staff who may detect unusual events for reporting; hospital leadership team members and planning department staff who are also the key decision-makers for determining the reporting process; and leaders and staff receiving reports at the preventive medicine centres (PMCs). We recruited participants from the GDPM (central governmental body in Ha Noi that oversees all PMCs), one DPMC, three provincial hospitals, four district hospitals and two private hospitals.

Data collection and analysis

Informed consent was obtained before conducting the interviews and focus group discussions. Three different semi-structured interview guides were developed and used to interview medical doctors, laboratory staff and hospital leadership teams. The focus group guide was developed and used to guide the discussion for provincial/district preventive medicine staff and hospital staff. Topics covered included the current reporting practice of unusual events, awareness, attitudes, potential barriers and solutions, and lessons learnt. Specific hypothetical scenarios were also used to identify possible actions that health-care workers may take upon detection of an unusual event. In addition, we also reviewed training records, logbooks and reporting forms to supplement interview data. Interviews and focus groups were led by experienced qualitative researchers, conducted in Vietnamese, and lasted approximately 60–90 minutes each; digital recordings of the sessions were transcribed verbatim for thematic analysis, which was performed in the NVIVO 8.0 software (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia). We conducted the data analysis simultaneously with data collection and data interpretation, which was iterative throughout the research process. We first used open coding to inductively classify data into initial categories or themes, which was then followed by axial coding to examine the data for regularities and variations within and between themes.9 The research team also met several times to discuss the key themes for verification and deepening the analysis of the results.

Ethical approval for this study

This study has been reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Board of Ha Noi University of Public Health in 2016.

RESULTS

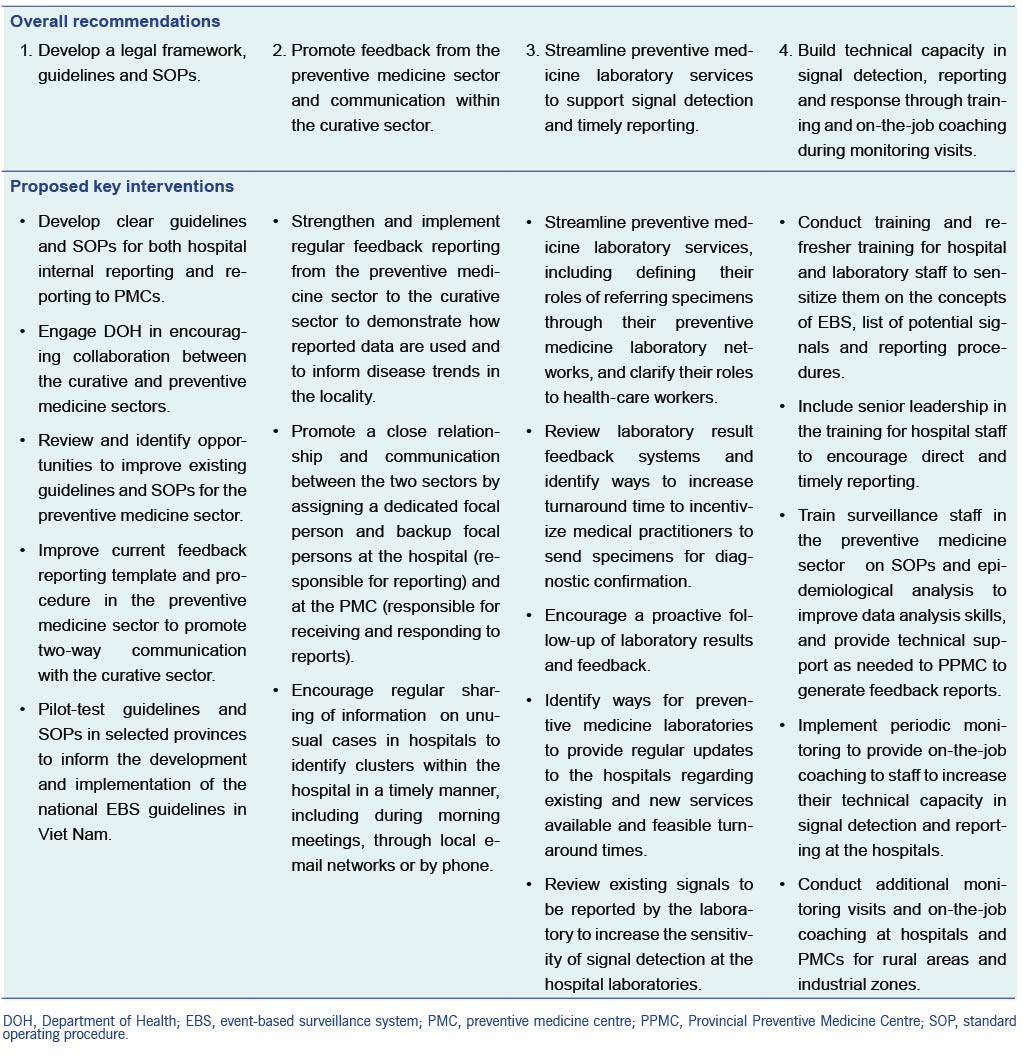

Five main themes emerged during the focus group discussions and in-depth interviews (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of key findings – the current situation for reporting “unusual events” from hospitals, Viet Nam, 2016

Theme 1 – Legal framework and standard operating procedures may play an important role in guiding reporting and response.

Hospital staff reported the lack of a legal framework and standard operating procedures (SOPs) as challenges that hinder event reporting. At the time of the study, no legal framework or national guidelines on EBS in Viet Nam existed. Although some institutions have their own internal reporting procedure, many do not. Some participants expressed their desire to have a more formalized system in place, as one hospital staff stated:

“At present, we haven’t got an official system to enable hospital departments to easily share information with provincial preventive medicine centres. So I think we should have a system in the future. I support this idea.”

Furthermore, no legal process is in place to mandate reporting. In non-residential industrial zones where there are only enterprises, manufacturers and companies producing industrial products and services, some companies reportedly tried to hide disease outbreaks among their employees due to the potential economic impact. Respondents reported that companies do not see it as their responsibility to report to the health authority, as explained by one PMC staff:

“The Department of Health at the provincial level needs to inform all companies to report infectious diseases to them. They need to inform our disease control department. They might hide an unusual outbreak [or] ignore it because they are afraid the media will announce the disease. We only [know] after they bring their family member to the hospital for treatment.”

Theme 2 – An enabling environment is necessary for timely reporting and response.

Hospital staff described several factors in their work environment that promote timely reporting.

- Supportive leadership. In hospitals with supportive leadership who believed in the value of reporting, timely reporting was not an issue. However, in hospitals with strict hierarchal reporting structures, staff may be punished, as one doctor explained:

- Availability of internal procedures to guide reporting. Limited guidance regarding the reporting process can create confusion among hospital staff. In hospitals with internal procedures, reporting was better implemented, as one doctor described:

- Good personal relationships between hospitals and PMCs. In provinces where there were good personal relationships between hospitals and PMCs, we saw enhanced crosstalk and event reporting. As one PMC staff explained:

- Assigned focal points at hospitals and PMCs to facilitate rapid information exchange. One key factor of success for prompt notification of unusual events has been assigning focal points at hospitals and PMCs. As one hospital staff mentioned:

"In case I report to the planning department without informing our head of department, the hospital director might ask, ‘Oh, what happened, does the head of the department know?’, and if he didn’t know, I am in trouble.”

“If I find an unusual case, first, we will discuss within our department. Then, I will report to the head of our department to confirm the case is unusual and requires further reporting. If it is, we will report to the leader who is in charge of that shift, or report to the planning department so that they can inform systematically.”

“The hospital often calls me if there is something unusual, no matter if it’s during or after working hours. They call me often; it is not under any system yet. … If something happens, we have to get a sample, so we send a person there straight away to get a sample. Then we will investigate the situation, perform tests quickly, and help them as soon as possible. After investigating at the hospital, we have to investigate the community as well.”

“One person at PMC is assigned to take care of each hospital or area. This is one favourable factor. They have an administrative landline and mobile to contact when they need. It’s important to have the responsible person to inform. We can report to the leader later. It’s quicker to inform the preventive medicine sector.”

Theme 3 – Potential benefits exist for the curative sector to work with the preventive medicine sector.

Hospital staff reported several potential benefits or factors that could prompt them or encourage them to report unusual events and work with the preventive medicine sector.

- Outbreak response and containment. One incentive to work with the preventive medicine sector is the support provided by PMCs during outbreaks. By informing PMCs of suspected outbreaks, hospitals are more likely to experience a timely response and outbreak containment, reducing the burden on hospitals. As one doctor explained:

- Knowledge of the local outbreak situation can increase doctors’ awareness and improve diagnosis, treatment and care. Knowing the epidemiological situation may help doctors in their clinical practice; however, reporting is often unidirectional, with no or limited feedback received after reporting. The same doctor summed up the reporting direction with PMC in one sentence:

- Laboratory confirmation by the preventive medicine network. Some doctors noted that confirmatory laboratory results help with diagnosis and treatment, and provide external feedback to hone clinical skills. Since hospital laboratory capacities are limited, clinicians benefit from PMC-facilitated laboratory testing through their laboratory network. One doctor explained:

“It is necessary to have prompt and quick actions to facilitate timely medical consultation and exams for more effective treatments. This would help the occurrence of outbreaks that we could prevent. We can then have a prompt response when an outbreak occurs.”

“We only report to them; we do not receive feedback from them.”

“We are clinical doctors; we want to have experience in diagnosis and treatment. We want to know how accurate our diagnoses are.”

However, laboratory testing in the preventive medicine sector is mainly for surveillance purposes. For diagnostic testing, long delays in receiving results preclude their use in patient diagnosis or treatment. Another doctor said:

“The preventive medicine centre delays the release of test results. I don’t know the reasons why, but they provide results so late that the patients have already been discharged. As a treating doctor, it’s difficult to treat a patient without having a confirmatory diagnosis.”

Theme 4 – Health-care providers face multiple challenges to timely reporting.

Hospital staff reported several challenges that prohibited timely event reporting from the curative sector.

- Reporting is not perceived to be the responsibility of hospital staff. Many doctors believe their focus should be on treatment and do not perceive reporting to be the task of the curative sector. Some doctors also think they are too busy to do reporting and are not familiar with reporting tasks. One doctor summed it up:

- Hospital staff do not see the value of reporting. Many doctors do not see the value or importance of reporting and how it can benefit them. Therefore, they do not prioritize the task of reporting. One doctor explained:

- No guidance or formal mechanisms in place. In the absence of national guidance and formal mechanisms, some hospitals have opted to have their own internal reporting procedure. This may require first getting approval by the Department of Planning before reporting to the preventive sector, which can delay timely reporting of an unusual event. As one hospital staff described:

- Hesitancy to report unless laboratory confirmation is available. Many doctors have a fear of being wrong or judged if a reported case turned out to be “not unusual”. Consequently, many doctors only want to report when laboratory confirmation is available. As one doctor explained:

“It’s more appropriate to ask the preventive medicine sector to do reports.”

“We have to do all different things; we don’t report straight away if we have too many things.”

“We collect cases every day and report to the hospital leaders before 7 PM. At the department level, we need to make a weekly report to send to the planning department; the planning department is in charge of sending it to the provincial department of health and the preventive medicine centre. They also check if the report is correct.”

“If later, after we’ve reported, the department of health finds out that the disease is just a normal or a common case, we are afraid that they will turn around and ask us why we could not diagnose an easy case.”

Theme 5 – Extra challenges exist for signal detection and reporting from remote areas and industrial zones.

Hospital and PMC staff reported additional difficulties in remote areas.

- Limited resources and experience. In remote areas, some clinicians found it difficult to recognize uncommon diseases. There is also a lack of local laboratory facilities; thus, treatment decisions were based solely on clinical judgment. For example, a hospital staff described a case of a patient with Coxsackie virus infection in a remote area who was neither referred to the infectious diseases department nor reported.

- Differences in language and culture. Other issues such as distance, language barriers and cultural barriers can also hinder early detection and timely reporting. One PMC staff mentioned the need to use law enforcement at times to “force” people who resisted medical care due to cultural reasons to go seek health care.

“The patient was only 4 months old. The patient had respiratory distress, so it was very hard to categorize. The treatment department said that the patient should be in the neurology department; it doesn’t matter if he has an infectious disease or not. We still face difficulties in categorizing patients, so we did not report.”

Another hospital staff reported a cluster of children with pertussis that was misdiagnosed as leukaemia given their unfamiliarity with the condition.

“There were several kids with the same cough and tests. At that time, I didn’t know what pertussis was like. … We didn’t think of pertussis because we haven’t seen [cases] for a very long time, so it’s very sudden. ... I didn’t know what to do. I explained to their families that it could be leukaemia, so we sent them to the Provincial General Hospital. The hospital did the same thing and sent them to the National Hematology and Blood Transfusion Hospital in Ha Noi. The doctors in the hospital witnessed the cough after two days; they thought it could be pertussis and treated the patient for pertussis. After that we had more and more similar patients coming.”

“We have to use law enforcement and follow the law of infectious diseases. The community did special things for the people who died, so people cannot go inside the houses during the three days after death. No one was allowed to go in. They would say, ‘This is my child, not yours, [and] even if they die, I can just give birth again.’ It’s complicated. So for our people’s health, we have to be strong, determined and do law enforcement. Sometimes we even had to ask [the] police to help in forcing them to go to the hospital for treatment.”

DISCUSSION

We found that hospital and laboratory staff were generally aware of what constituted an “unusual event”. Our study further identified facilitators and barriers to timely reporting. Close relationships between hospitals and PMCs facilitated timely reporting and rapid public health response. In addition, instituting focal points at the hospitals and PMCs further clarified roles and responsibilities and facilitated the reporting process. Key issues that hindered early detection and timely reporting included clinicians not considering reporting as their role; uncertainty regarding the reporting process; a lengthy approval process for reporting in some hospitals; hesitancy to report before confirmatory diagnostic testing; and challenge in recognizing clusters within the hospital. The one-way reporting process with minimal feedback from the preventive medicine sector also discouraged reporting.

Fostering a “win-win” relationship between health-care and public health systems

A common theme seen in this study and previous studies in other contexts was the need to strengthen the relationship between the curative and preventive medicine sectors to ensure two-way communication.3 Although most studies investigating different ways to motivate reporting were for routine reporting through the indicator-based surveillance (IBS) system, we believe it is also applicable to reporting rare and unusual events through the EBS system.

To facilitate reporting from health-care workers to the public health system, health-care workers also need tangible benefits of working with the public health system. In other words, it is important to foster a “win-win” relationship between health care and public health systems. Some study participants believed that information on national and local outbreaks would help their ability to diagnose and treat their patients. Previous studies have recommended generating a feedback report and ensuring they reach reporters, so they see the value in reporting.10–12 Other studies have shown that tailoring feedback to focus on the current outbreaks and other information of interest to medical staff can also encourage reporting.13 We also believe this may be an important approach that promotes ownership.

Laboratory services at PMCs may also help physicians at health-care facilities with their clinical practice in the diagnosis of infectious diseases. We did note that depending on the province, some laboratory services in the preventive medicine sector were not able to fulfil the physicians’ expectations. We believe streamlining preventive medicine laboratory services could contribute to the strengthening of the working relationship of the health-care and public health systems, and thus, in turn, promote the early detection of outbreaks and public health events.

Raising awareness on the value of reporting

Many medical professionals in our study did not perceive that reporting events was their responsibility. In addition, they were not fully aware of what, how and when to report, as we have seen in other countries.3,10,11,14 Passive attitudes, lack of knowledge regarding reporting requirements and misconceptions regarding the value of reporting seen in our study have been previously observed.3,10,11,14,15 Certain beliefs, knowledge and attitudes held by physicians, such as the ones we saw in our study, are associated with underreporting.15 These findings point to the need to raise awareness of the value of reporting among medical staff.

For some medical professionals, it may be difficult to recognize the importance of a rare event. One possible strategy is to present scenarios and lessons learnt from past outbreaks such as the 2015 Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak in the Republic of Korea, which dampened economic growth and impacted the reputation of some hospitals. Describing the role of medical professionals in these past outbreaks may help providers embrace their unique position as the guardians at the first line of defence.16,17 A previous study has also suggested the use of financial incentives or a penalty system to encourage reporting.11 Different approaches to motivate reporting among medical staff, specifically in Viet Nam, may need to be explored. With a longer vision in mind, a strong sense of ownership and expanded responsibility of their role as reporters may need to be cultivated during the training and sensitization process.

Creating an enabling environment for reporting

Although raising awareness among medical staff may increase their motivation to report, individual motivation depends on an enabling environment that facilitates reporting. In this study, participants expressed a lack of knowledge of the reporting process. Study participants also revealed that the reporting process could be lengthy, given the layers of approval required at many hospitals. Hospitals that empower their staff to report immediately to the PMC are the minority. We believe that creating an enabling environment is critical for the success of an EBS system. An enabling environment includes clear guidelines that signate a responsible focal person, describe the roles and responsibilities and lines of reporting, and establish goals and expectations. In addition, staff should be provided with the means needed to report and have leadership support to ensure that the responsible person has protected time allocated for reporting activities. Finally, training of new staff and regular re-training of existing staff may be an important way to continually sensitize the medical staff.18

Promoting a simple and flexible reporting process

Developing a process for event reporting that is appropriate for all 63 provinces in Viet Nam is challenging, given their differences in resources and workforce capacity. Therefore, keeping the system flexible, and having the ability to tailor the system to the capability of each province, may be one of the key factors for success. Previous studies have shown that the implicity of the reporting system is one of the most important factors to encourage reporting from clinicians.10,11,13,14

Limitations

The findings in this study represent only the views of the purposefully selected hospital and preventive medicine staff in four provinces in Viet Nam; therefore, the generalizability of the findings may be limited. In addition, this was an exploratory study carried out for public health practice, which we focused on obtaining in-depth insights and synthesizing the information from all sources into key themes that were actionable instead of a comparative analysis study. Therefore, we did not present on the differences between the provinces, or the responses from key informants who were in different roles or at various levels of the organization. For the same reasons, a certain level of flexibility was required in sample selection; depending on facility size and availability of staff, in rare occasions, focus group discussions also had fewer than five participants.

CONCLUSIONS

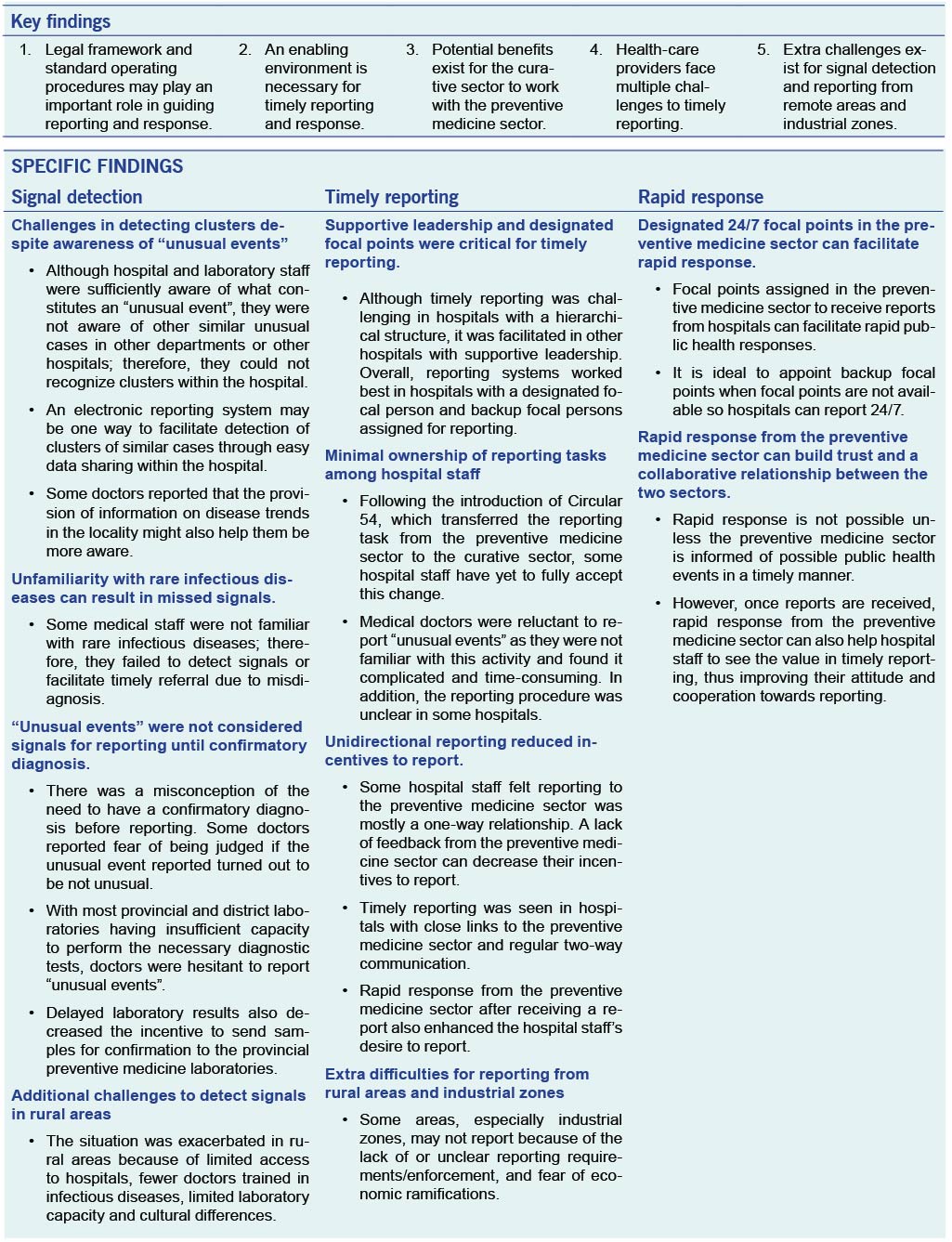

In this study, we showed that an enabling environment is critical for timely event reporting. This encompasses multiple components such as having leadership support, a good relationship between the two sectors, clear guidance on the process of reporting, and focal points to streamline reporting. However, we believe the fundamental key to success for both IBS and EBS is cultivating a “win-win” relationship between the curative and preventive medicine sectors, where both sides can see the value and benefits of this synergistic collaboration. Moving forward, as outlined in Table 2, we believe there are priority actions that can be taken to strengthen this important relationship further and ultimately to improve the overall health security system in Viet Nam.