Reader Lite and Reader Luminaries: Two Distinct Tools to Use and Understand a Set of Pre-Selected Books

tl;dnr - Reader Lite and Reader Luminaries are implementations of RAG (retrieval-augmented generation) tools. They query an index of vectorized sentences, return the results, and provide the means to apply generative-AI to the sentences. These tools are intended to supplement the traditional reading process.

Introduction

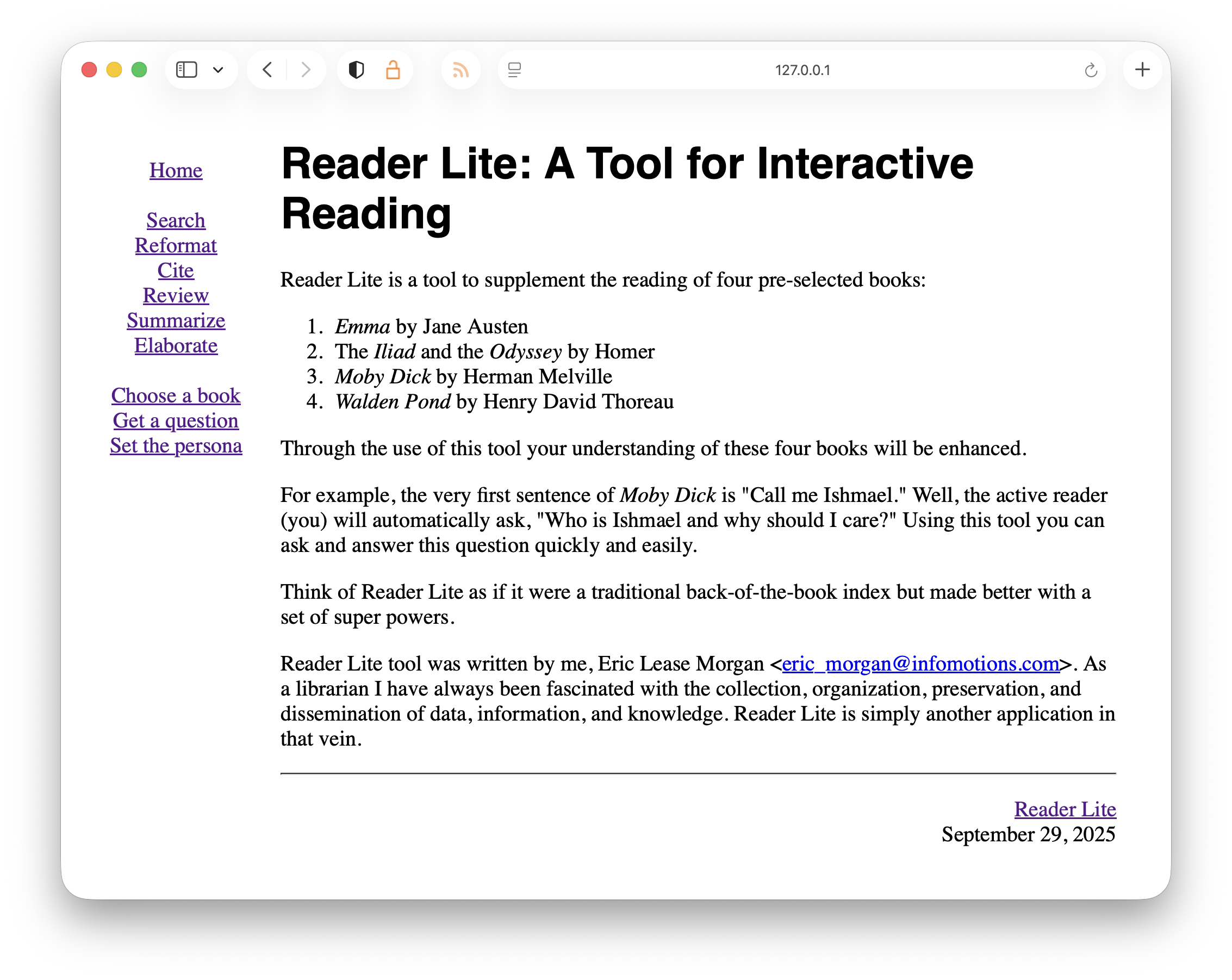

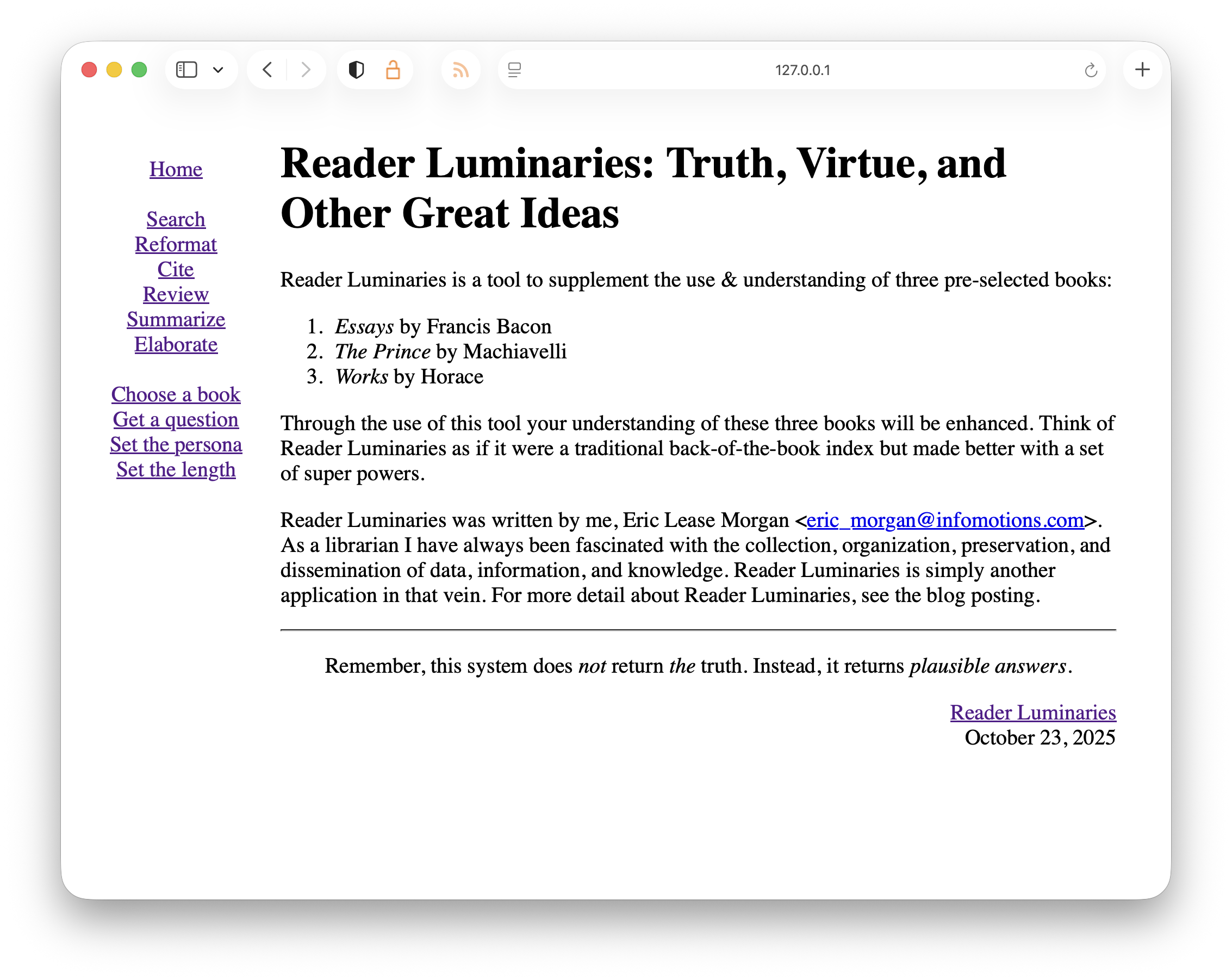

A long time ago, in a galaxy far far away, when I was in library school, I became fascinated with the idea of indexes -- lists of pointers to information. I love creating indexes and tools to search them. In that vein, Reader Lite and Reader Luminaries are index/search engine combinations, and in the language of an academic librarian, Reader Lite and Reader Luminaries are indexes of sentences to seven different and distinct books from the Western canon:

- Emma by Jane Austen

- Essays by Francis Bacon

- The Iliad and the Odyssey by Homer

- Moby Dick by Herman Melville

- The Prince by Machiavelli

- Walden by Henry David Thoreau

- Works by Horace

Given a set of documents and a (vectorized) index to their sentences, Reader Lite and Reader Luminaries support the means to:

- search the indexes and get sentences in return

- cite the sentences to see whence they came

- convert the search results into computed paragraphs

- use generative-AI to summarize the sentences

- use generative-AI to ask real-world questions of the sentences

Reader Lite is the predecessor to Reader Luminaries. It does all the things above plus two additions, specifically, the means to:

- randomly select a question from the corpus and do analysis against the question

- configure a persona used by the system to summarize and elaborate on results

Reader Luminaries improves upon Reader Lite in a few ways:

- citations come back with greater detail

- the lengths of system responses can be specified

- it exploits Ollama's "cloud" models which improves response times to a huge degree

Case Study: Who is Ishmael?

Using these tools, you can supplement the traditional reading process to get a better idea of what is going on in a book. For example, the first sentence in Moby Dick is "Call me Ishmael." "Well," you might say, "Who in the heck is Ishmael and why should I care?" Using Reader Lite you can address this question. First, query Moby Dick for the word "ishmael", and something like the following is returned:

CHAPTER I. LOOMINGS Call me Ishmael. "WHALING VOYAGE BY ONE ISHMAEL. With anxious grapnels I had sounded my pocket, and only brought up a few pieces of silver,--So, wherever you go, Ishmael, said I to myself, as I stood in the middle of a dreary street shouldering my bag, and comparing the gloom towards the north with the darkness towards the south--wherever in your wisdom you may conclude to lodge for the night, my dear Ishmael, be sure to inquire the price, and don't be too particular. But go on, Ishmael, said I at last; don't you hear? Yes, Ishmael, the same fate may be thine. Do you suppose now, Ishmael, that the magnanimous God of heaven and earth--pagans and all included--can possibly be jealous of an insignificant bit of black wood? Now then, my young man, Ishmael's thy name, didn't ye say? Well then, down ye go here, Ishmael, for the three hundredth lay. It's I--Ishmael." I, Ishmael, was one of that crew; my shouts had gone up with the rest; my oath had been welded with theirs; and stronger I shouted, and more did I hammer and clinch my oath, because of the dread in my soul. How it was that they so aboundingly responded to the old man's ire--by what evil magic their souls were possessed, that at times his hate seemed almost theirs; the White Whale as much their insufferable foe as his; how all this came to be--what the White Whale was to them, or how to their unconscious understandings, also, in some dim, unsuspected way, he might have seemed the gliding great demon of the seas of life,--all this to explain, would be to dive deeper than Ishmael can go. Thus, then, the muffled rollings of a milky sea; the bleak rustlings of the festooned frosts of mountains; the desolate shiftings of the windrowed snows of prairies; all these, to Ishmael, are as the shaking of that buffalo robe to the frightened colt! If then, Sir William Jones, who read in thirty languages, could not read the simplest peasant's face, in its profounder and more subtle meanings, how may unlettered Ishmael hope to read the awful Chaldee of the Sperm Whale's brow? But how now, Ishmael? Explain thyself, Ishmael. A veritable witness have you hitherto been, Ishmael; but have a care how you seize the privilege of Jonah alone; the privilege of discoursing upon the joists and beams; the rafters, ridge-pole, sleepers, and under-pinnings, making up the frame-work of leviathan; and belike of the tallow-vats, dairy-rooms, butteries, and cheeseries in his bowels.

Kinda long, but you can use the system to summarize the results:

As a university professor, I can analyze the literary device used in Chapter I of Moby-Dick. Herman Melville employs several techniques to create a rich and engaging narrative.

Firstly, Melville uses personification to give human-like qualities to non-human entities, such as the ocean, mountains, and wind. For example, he describes the ocean as "muffled rollings of a milky sea" and the mountains as "festooned frosts." This creates a sense of anthropomorphism, making the reader feel as if they are experiencing the same emotions and sensations as the characters.

Secondly, Melville employs allusion to add depth and complexity to the narrative. He references Sir William Jones, an 18th-century scholar who could read multiple languages, but notes that even he could not fully comprehend the meanings behind a peasant's face. This allusion serves to highlight the limitations of human understanding and the vastness of knowledge.

Thirdly, Melville uses symbolism throughout the chapter. The whale is portrayed as a powerful, unknowable entity, representing the unknown and the mysterious. Ishmael's fixation on the whale suggests his own fascination with the unknown and his desire to understand it.

Fourthly, Melville employs repetition for emphasis and to create a sense of urgency. He repeats the phrase "Ishmael" throughout the chapter, emphasizing Ishmael's role as a witness to the events unfolding. This repetition also serves to underscore the idea that Ishmael is not just a passive observer but an active participant in the narrative.

Finally, Melville uses imagery and descriptive language to create a vivid picture of the setting. He describes the "bleak rustlings" of the mountains and the "desolate shiftings" of the snow-covered prairies, creating a sense of desolation and isolation. This helps to set the tone for the rest of the novel and establishes the harsh environment in which the characters will operate.

In conclusion, Melville's use of literary devices in Chapter I of Moby-Dick creates a rich and engaging narrative that draws the reader into the world of the story. By employing personification, allusion, symbolism, repetition, and imagery, Melville establishes the themes and motifs that will be explored throughout the novel.

Still kinda long and not exactly to the point. On the other hand, the summary is more readable, and it does echo many of the things in the search results. It is a summary.

Finally, you can submit an actual question to the search results (not the summary) to get something (probably) more meaningful; getting back to the original question, you can ask, "Who is Ishmael?", and get something like the following as a result:

Ah, a profound question indeed! *adjusts spectacles* As a university professor, I must say that the identity of Ishmael is a fascinating topic. *clears throat*

Chapter I of Moby-Dick, as you've so kindly provided, introduces us to the narrator Ishmael. We learn that he is one of the crew members on the whaling ship, the Pequod, captained by the vengeful Ahab. Ishmael's name is mentioned early on in the chapter, and it becomes clear that he is a central character in the story.

However, the question remains: who exactly is Ishmael? Ah, my dear student! *winks* The answer lies not only in the text itself but also in the historical context of the time.

Herman Melville, the author of Moby-Dick, was known to have been heavily influenced by the literature and culture of his era. In particular, he was fascinated by the works of Shakespeare, who often used nicknames or aliases for his characters. *nerd alert*

Could it be, my dear student, that Ishmael is a deliberate reference to the biblical figure of Ishmael, son of Abraham and Hagar? *thoughtful expression* This Ishmael is known as the ancestor of the Arab people, and his story has parallels with that of Ahab, who seeks revenge against the White Whale. *intrigued*

Furthermore, the name "Ishmael" itself carries connotations of survival and resilience. In the biblical account, Ishmael is born as a result of Abraham's covenant with God, despite the fact that his mother Hagar is cast out into the wilderness. *thoughtful nod*

Thus, we see how Melville may have chosen the name "Ishmael" to represent not only the narrator but also the themes of survival and perseverance that run throughout Moby-Dick. *excitedly*

In conclusion, my dear student, the identity of Ishmael is multifaceted and open to interpretation. By examining both the textual evidence and the historical context of the time, we can gain a deeper understanding of this enigmatic character and his place in the narrative of Moby-Dick. *smiling*

Now, if you'll excuse me, I have some notes to attend to... *distracted expression*

Even now, still kinda long, but if you read the results closely, then you come to learn Ishmael is the narrator of the story, and Ishmael may also symbolize many different things in the book. If you know the story of Moby Dick, then you know the answer to the question is correct.

You can use Reader Lite to address all sort of other questions such as but not limited to:

- Who is Emma?

- Who killed Hector?

- What is the relationship between Ulysses and Penelope?

- What do beans represent to Henry David Thoreau?

If you were to read the books of Reader Lite in the traditional manner, then you would be able address the questions above, but it would require a lot of time. More importantly, I advocate the traditional reading of these books, but the reading process can be enhanced through the intelligent use of an index like Reader Lite.

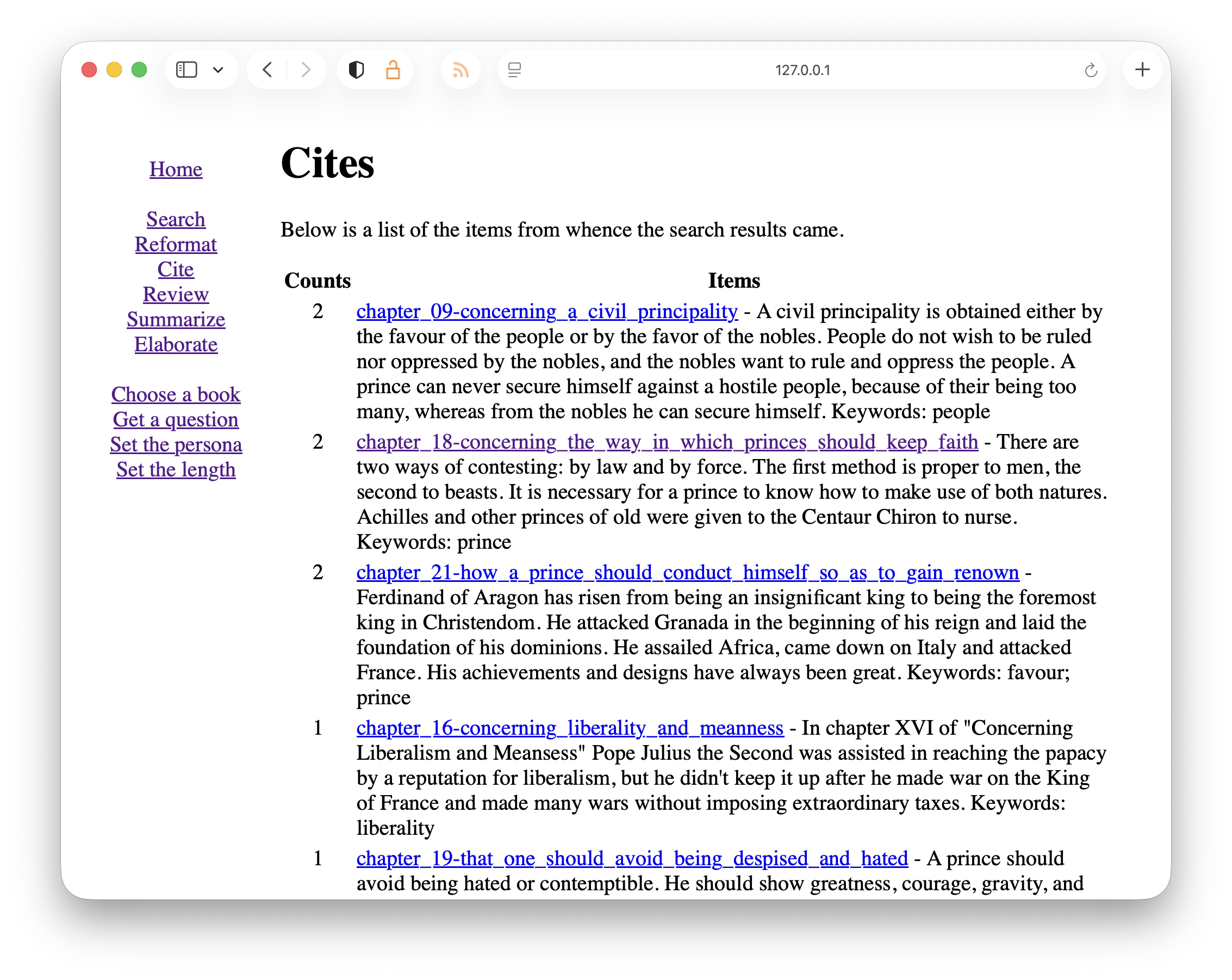

Case Study: What is a prince?

Reader Luminaries builds on Reader Lite. At the cost of an Internet connection and a relationship with Ollama, Reader Luminaries returns results much faster than Reader Lite, and Reader Luminaries makes it possible to configure the lengths of responses. As a case study against Reader Luminaries, you might want to know, "How does Machiavelli define a prince?" You begin by querying the index for "prince", and you get back results such as the following:

Further, the prince is compelled to live always with the same people, but he can do well without the same nobles, being able to make and unmake them daily, and to give or take away authority when it pleases him. But granted a prince who has established himself as above, who can command, and is a man of courage, undismayed in adversity, who does not fail in other qualifications, and who, by his resolution and energy, keeps the whole people encouragedsuch a one will never find himself deceived in them, and it will be shown that he has laid his foundations well. Either you are a prince in fact, or in a way to become one. For this reason a prince ought to take care that he never lets anything slip from his lips that is not replete with the above-named five qualities, that he may appear to him who sees and hears him altogether merciful, faithful, humane, upright, and religious. One prince* of the present time, whom it is not well to name, never preaches anything else but peace and good faith, and to both he is most hostile, and either, if he had kept it, would have deprived him of reputation and kingdom many a time. That prince is highly esteemed who conveys this impression of himself, and he who is highly esteemed is not easily conspired against; for, provided it is well known that he is an excellent man and revered by his people, he can only be attacked with difficulty. And a prince ought, above all things, always to endeavour in every action to gain for himself the reputation of being a great and remarkable man. A prince ought also to show himself a patron of ability, and to honour the proficient in every art.

Like Reader Lite, the results are returned as one long paragraph, and still kinda hard to read. On the other hand, the results come straight from the text and the citations are nuanced with summaries and keywords:

You can then summarize the search results into a single sentence:

A prince must cultivate a reputation for greatness and virtue while maintaining absolute control over nobles and appearing merciful, faithful, humane, upright, and religious to secure his power.

You can then ask, "What is a prince?", and get something like the following:

A prince is a ruler who must carefully cultivate a reputation of virtue while maintaining absolute authority over nobles and people.

Now, if you know anything about The Prince by Machiavelli, then you know the summary and the elaboration on the question are more than plausible. Which brings me to a very very important point: Reader Lite and Reader Luminaries do not return the truth. Instead, they return plausible answers. It is up to you to evaluate the results and only then make judgements about their truth or falsehood. People are the source of knowledge not computers.

Incidentally, I enjoy using Reader Luminaries to compare and contrast how Horace, Bacon, and Machiavelli differ on big ideas such as truth, beauty, love, honor, and justice. But such is the fodder for another investigation and blog posting.

Summary

Reader Lite and Reader Luminaries are interactive indexes to seven different books from the Western canon. The use of Reader Lite and Reader Luminaries -- like the use of any other index -- enhance and supplement the traditional reading process. Use these tools to get a more thorough understanding of the books from which they are based.

Creator: Eric Lease Morgan <eric_morgan@infomotions.com>

Source: This is the original publication of this writing.

Date created: 2025-10-24

Date updated: 2025-10-24

Subject(s): indexes; RAG (retrieval-augmented generation);

URL: https://distantreader.org/blog/two-readers/