Plato

Plato | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 428/427 or 424/423 BC |

| Died | 348/347 BC (age c. 80) Athens, Greece |

Notable work | |

| Era | Ancient Greek philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Platonism |

| Notable students | |

Main interests | |

Notable ideas | |

Influenced

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Platonism |

|---|

|

| Allegories and metaphors |

| Related articles |

| Related categories |

|

► Plato |

Plato (/ˈpleɪtoʊ/ PLAY-toe;[2] Greek: Πλάτων Plátōn, pronounced [plá.tɔːn] in Classical Attic; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was an Athenian philosopher during the Classical period in Ancient Greece, founder of the Platonist school of thought, and the Academy, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world.

He is widely considered the pivotal figure in the history of Ancient Greek and Western philosophy, along with his teacher, Socrates, and his most famous student, Aristotle.[a] Plato has also often been cited as one of the founders of Western religion and spirituality.[4] The so-called Neoplatonism of philosophers like Plotinus and Porphyry greatly influenced Christianity through Church Fathers such as Augustine. Alfred North Whitehead once noted: "the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato."[5]

Plato was the innovator of the written dialogue and dialectic forms in philosophy. Plato is also considered the founder of Western political philosophy. His most famous contribution is the theory of Forms known by pure reason, in which Plato presents a solution to the problem of universals known as Platonism (also ambiguously called either Platonic realism or Platonic idealism). He is also the namesake of Platonic love and the Platonic solids.

His own most decisive philosophical influences are usually thought to have been along with Socrates, the pre-Socratics Pythagoras, Heraclitus and Parmenides, although few of his predecessors' works remain extant and much of what we know about these figures today derives from Plato himself.[b] Unlike the work of nearly all of his contemporaries, Plato's entire body of work is believed to have survived intact for over 2,400 years.[7] Although their popularity has fluctuated over the years, the works of Plato have never been without readers since the time they were written.[8]

Biography

Early life

Birth and family

Due to a lack of surviving accounts, little is known about Plato's early life and education. Plato belonged to an aristocratic and influential family. According to a disputed tradition, reported by doxographer Diogenes Laërtius, Plato's father Ariston traced his descent from the king of Athens, Codrus, and the king of Messenia, Melanthus.[9] According to the ancient Hellenic tradition, Codrus was said to have been descended from the mythological deity Poseidon.[10][11]

Plato's mother was Perictione, whose family boasted of a relationship with the famous Athenian lawmaker and lyric poet Solon, one of the seven sages, who repealed the laws of Draco (except for the death penalty for homicide).[11] Perictione was sister of Charmides and niece of Critias, both prominent figures of the Thirty Tyrants, known as the Thirty, the brief oligarchic regime (404–403 BC), which followed on the collapse of Athens at the end of the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC).[12] According to some accounts, Ariston tried to force his attentions on Perictione, but failed in his purpose; then the god Apollo appeared to him in a vision, and as a result, Ariston left Perictione unmolested.[13]

The exact time and place of Plato's birth are unknown. Based on ancient sources, most modern scholars believe that he was born in Athens or Aegina[c] between 429 and 423 BC, not long after the start of the Peloponnesian War.[d] The traditional date of Plato's birth during the 87th or 88th Olympiad, 428 or 427 BC, is based on a dubious interpretation of Diogenes Laërtius, who says, "When [Socrates] was gone, [Plato] joined Cratylus the Heracleitean and Hermogenes, who philosophized in the manner of Parmenides. Then, at twenty-eight, Hermodorus says, [Plato] went to Euclides in Megara." However, as Debra Nails argues, the text does not state that Plato left for Megara immediately after joining Cratylus and Hermogenes.[23] In his Seventh Letter, Plato notes that his coming of age coincided with the taking of power by the Thirty, remarking, "But a youth under the age of twenty made himself a laughingstock if he attempted to enter the political arena." Thus, Nails dates Plato's birth to 424/423.[24]

According to Neanthes, Plato was six years younger than Isocrates, and therefore was born the same year the prominent Athenian statesman Pericles died (429 BC).[25] Jonathan Barnes regards 428 BC as the year of Plato's birth.[21][22] The grammarian Apollodorus of Athens in his Chronicles argues that Plato was born in the 88th Olympiad.[18] Both the Suda and Sir Thomas Browne also claimed he was born during the 88th Olympiad.[17][26] Another legend related that, when Plato was an infant, bees settled on his lips while he was sleeping: an augury of the sweetness of style in which he would discourse about philosophy.[27]

Besides Plato himself, Ariston and Perictione had three other children; two sons, Adeimantus and Glaucon, and a daughter Potone, the mother of Speusippus (the nephew and successor of Plato as head of the Academy).[12] The brothers Adeimantus and Glaucon are mentioned in the Republic as sons of Ariston,[28] and presumably brothers of Plato, though some have argued they were uncles.[e] In a scenario in the Memorabilia, Xenophon confused the issue by presenting a Glaucon much younger than Plato.[30]

Ariston appears to have died in Plato's childhood, although the precise dating of his death is difficult.[31] Perictione then married Pyrilampes, her mother's brother,[32] who had served many times as an ambassador to the Persian court and was a friend of Pericles, the leader of the democratic faction in Athens.[33] Pyrilampes had a son from a previous marriage, Demus, who was famous for his beauty.[34] Perictione gave birth to Pyrilampes' second son, Antiphon, the half-brother of Plato, who appears in Parmenides.[35]

In contrast to his reticence about himself, Plato often introduced his distinguished relatives into his dialogues, or referred to them with some precision. In addition to Adeimantus and Glaucon in the Republic, Charmides has a dialogue named after him; and Critias speaks in both Charmides and Protagoras.[36] These and other references suggest a considerable amount of family pride and enable us to reconstruct Plato's family tree. According to Burnet, "the opening scene of the Charmides is a glorification of the whole [family] connection ... Plato's dialogues are not only a memorial to Socrates, but also the happier days of his own family."[37]

Name

The fact that the philosopher in his maturity called himself Platon is indisputable, but the origin of this name remains mysterious. Platon is a nickname from the adjective platýs (πλατύς) 'broad'. Although Platon was a fairly common name (31 instances are known from Athens alone),[38] the name does not occur in Plato's known family line.[39] The sources of Diogenes Laërtius account for this by claiming that his wrestling coach, Ariston of Argos, dubbed him "broad" on account of his chest and shoulders, or that Plato derived his name from the breadth of his eloquence, or his wide forehead.[40][41] While recalling a moral lesson about frugal living Seneca mentions the meaning of Plato's name: "His very name was given him because of his broad chest."[42]

His true name was supposedly Aristocles (Ἀριστοκλῆς), meaning 'best reputation'.[f] According to Diogenes Laërtius, he was named after his grandfather, as was common in Athenian society.[43] But there is only one inscription of an Aristocles, an early archon of Athens in 605/4 BC. There is no record of a line from Aristocles to Plato's father, Ariston. Recently a scholar has argued that even the name Aristocles for Plato was a much later invention.[44] However, another scholar claims that "there is good reason for not dismissing [the idea that Aristocles was Plato's given name] as a mere invention of his biographers", noting how prevalent that account is in our sources.[39]

Education

Ancient sources describe him as a bright though modest boy who excelled in his studies. Apuleius informs us that Speusippus praised Plato's quickness of mind and modesty as a boy, and the "first fruits of his youth infused with hard work and love of study".[45] His father contributed all which was necessary to give to his son a good education, and, therefore, Plato must have been instructed in grammar, music, and gymnastics by the most distinguished teachers of his time.[46] Plato invokes Damon many times in the Republic. Plato was a wrestler, and Dicaearchus went so far as to say that Plato wrestled at the Isthmian games.[47] Plato had also attended courses of philosophy; before meeting Socrates, he first became acquainted with Cratylus and the Heraclitean doctrines.[48]

Ambrose believed that Plato met Jeremiah in Egypt and was influenced by his ideas. Augustine initially accepted this claim, but later rejected it, arguing in The City of God that "Plato was born a hundred years after Jeremiah prophesied."[49][need quotation to verify]

Later life and death

Plato may have travelled in Italy, Sicily, Egypt and Cyrene.[50]Plato's own statement was that he visited Italy and Sicily at the age of forty and was disgusted by the sensuality of life there. Said to have returned to Athens at the age of forty, Plato founded one of the earliest known organized schools in Western Civilization on a plot of land in the Grove of Hecademus or Academus.[51] The Academy was a large enclosure of ground about six stadia outside of Athens proper. One story is that the name of the Academy comes from the ancient hero, Academus; still another story is that the name came from a supposed former owner of the plot of land, an Athenian citizen whose name was (also) Academus; while yet another account is that it was named after a member of the army of Castor and Pollux, an Arcadian named Echedemus.[52] The Academy operated until it was destroyed by Lucius Cornelius Sulla in 84 BC. Many intellectuals were schooled in the Academy, the most prominent one being Aristotle.[53][54]

Throughout his later life, Plato became entangled with the politics of the city of Syracuse. According to Diogenes Laërtius, Plato initially visited Syracuse while it was under the rule of Dionysius.[55] During this first trip Dionysius's brother-in-law, Dion of Syracuse, became one of Plato's disciples, but the tyrant himself turned against Plato. Plato almost faced death, but he was sold into slavery.[g] Anniceris, a Cyrenaic philosopher, subsequently bought Plato's freedom for twenty minas,[57] and sent him home. After Dionysius's death, according to Plato's Seventh Letter, Dion requested Plato return to Syracuse to tutor Dionysius II and guide him to become a philosopher king. Dionysius II seemed to accept Plato's teachings, but he became suspicious of Dion, his uncle. Dionysius expelled Dion and kept Plato against his will. Eventually Plato left Syracuse. Dion would return to overthrow Dionysius and ruled Syracuse for a short time before being usurped by Calippus, a fellow disciple of Plato.

According to Seneca, Plato died at the age of 81 on the same day he was born.[58] The Suda indicates that he lived to 82 years,[17] while Neanthes claims an age of 84.[18] A variety of sources have given accounts of his death. One story, based on a mutilated manuscript,[59] suggests Plato died in his bed, whilst a young Thracian girl played the flute to him.[60] Another tradition suggests Plato died at a wedding feast. The account is based on Diogenes Laërtius's reference to an account by Hermippus, a third-century Alexandrian.[61] According to Tertullian, Plato simply died in his sleep.[61]

Plato owned an estate at Iphistiadae, which by will he left to a certain youth named Adeimantus, presumably a younger relative, as Plato had an elder brother or uncle by this name.

Influences

Pythagoras

Although Socrates influenced Plato directly as related in the dialogues, the influence of Pythagoras upon Plato, or in a broader sense, the Pythagoreans, such as Archytas also appears to have been significant. Aristotle claimed that the philosophy of Plato closely followed the teachings of the Pythagoreans,[62] and Cicero repeats this claim: "They say Plato learned all things Pythagorean."[63] It is probable that both were influenced by Orphism, and both believed in metempsychosis, transmigration of the soul.

Pythagoras held that all things are number, and the cosmos comes from numerical principles. He introduced the concept of form as distinct from matter, and that the physical world is an imitation of an eternal mathematical world. These ideas were very influential on Heraclitus, Parmenides and Plato.[64]

George Karamanolis notes that

Numenius accepted both Pythagoras and Plato as the two authorities one should follow in philosophy, but he regarded Plato's authority as subordinate to that of Pythagoras, whom he considered to be the source of all true philosophy—including Plato's own. For Numenius it is just that Plato wrote so many philosophical works, whereas Pythagoras' views were originally passed on only orally.[65]

According to R. M. Hare, this influence consists of three points:

- The platonic Republic might be related to the idea of "a tightly organized community of like-minded thinkers", like the one established by Pythagoras in Croton.

- The idea that mathematics and, generally speaking, abstract thinking is a secure basis for philosophical thinking as well as "for substantial theses in science and morals".

- They shared a "mystical approach to the soul and its place in the material world".[66][67]

Plato and mathematics

Plato may have studied under the mathematician Theodorus of Cyrene, and has a dialogue named for and whose central character is the mathematician Theaetetus. While not a mathematician, Plato was considered an accomplished teacher of mathematics. Eudoxus of Cnidus, the greatest mathematician in Classical Greece, who contributed much of what is found in Euclid's Elements, was taught by Archytas and Plato. Plato helped to distinguish between pure and applied mathematics by widening the gap between "arithmetic", now called number theory and "logistic", now called arithmetic.[h]

In the dialogue Timaeus Plato associated each of the four classical elements (earth, air, water, and fire) with a regular solid (cube, octahedron, icosahedron, and tetrahedron respectively) due to their shape, the so-called Platonic solids. The fifth regular solid, the dodecahedron, was supposed to be the element which made up the heavens.

Heraclitus and Parmenides

The two philosophers Heraclitus and Parmenides, following the way initiated by pre-Socratic Greek philosophers like Pythagoras, depart from mythology and begin the metaphysical tradition that strongly influenced Plato and continues today.[64]

The surviving fragments written by Heraclitus suggest the view that all things are continuously changing, or becoming. His image of the river, with ever-changing waters, is well known. According to some ancient traditions like that of Diogenes Laërtius, Plato received these ideas through Heraclitus' disciple Cratylus, who held the more radical view that continuous change warrants scepticism because we cannot define a thing that does not have a permanent nature.[69]

Parmenides adopted an altogether contrary vision, arguing for the idea of changeless Being and the view that change is an illusion.[64] John Palmer notes "Parmenides' distinction among the principal modes of being and his derivation of the attributes that must belong to what must be, simply as such, qualify him to be seen as the founder of metaphysics or ontology as a domain of inquiry distinct from theology."[70]

These ideas about change and permanence, or becoming and Being, influenced Plato in formulating his theory of Forms.[69]

Plato's most self-critical dialogue is called Parmenides, featuring Parmenides and his student Zeno, who following Parmenides' denial of change argued forcefully with his paradoxes to deny the existence of motion.

Plato's Sophist dialogue includes an Eleatic stranger, a follower of Parmenides, as a foil for his arguments against Parmenides. In the dialogue Plato distinguishes nouns and verbs, providing some of the earliest treatment of subject and predicate. He also argues that motion and rest both "are", against followers of Parmenides who say rest is but motion is not.

Socrates

Plato was one of the devoted young followers of Socrates. The precise relationship between Plato and Socrates remains an area of contention among scholars.

Plato never speaks in his own voice in his dialogues, and speaks as Socrates in all but the Laws. In the Second Letter, it says, "no writing of Plato exists or ever will exist, but those now said to be his are those of a Socrates become beautiful and new";[71] if the Letter is Plato's, the final qualification seems to call into question the dialogues' historical fidelity. In any case, Xenophon's Memorabilia and Aristophanes's The Clouds seem to present a somewhat different portrait of Socrates from the one Plato paints. The Socratic problem asks how to reconcile these various accounts. Leo Strauss notes that Socrates' reputation for irony casts doubt on whether Plato's Socrates is expressing sincere beliefs.[72]

Aristotle attributes a different doctrine with respect to Forms to Plato and Socrates.[73] Aristotle suggests that Socrates' idea of forms can be discovered through investigation of the natural world, unlike Plato's Forms that exist beyond and outside the ordinary range of human understanding. In the dialogues of Plato though, Socrates sometimes seems to support a mystical side, discussing reincarnation and the mystery religions, this is generally attributed to Plato.[clarification needed][74] Regardless, this view of Socrates cannot be dismissed out of hand, as we cannot be sure of the differences between the views of Plato and Socrates. In the Meno Plato refers to the Eleusinian Mysteries, telling Meno he would understand Socrates's answers better if he could stay for the initiations next week. It is possible that Plato and Socrates took part in the Eleusinian Mysteries.[75]

Philosophy

Metaphysics

In Plato's dialogues, Socrates and his company of disputants had something to say on many subjects, including several aspects of metaphysics. These include religion and science, human nature, love, and sexuality. More than one dialogue contrasts perception and reality, nature and custom, and body and soul.

The Forms

"Platonism" and its theory of Forms (or theory of Ideas) denies the reality of the material world, considering it only an image or copy of the real world. The theory of Forms is first introduced in the Phaedo dialogue (also known as On the Soul), wherein Socrates refutes the pluralism of the likes of Anaxagoras, then the most popular response to Heraclitus and Parmenides, while giving the "Opposites Argument" in support of the Forms.

According to this theory of Forms there are at least two worlds: the apparent world of concrete objects, grasped by the senses, which constantly changes, and an unchanging and unseen world of Forms or abstract objects, grasped by pure reason (λογική). which ground what is apparent.

It can also be said there are three worlds, with the apparent world consisting of both the world of material objects and of mental images, with the "third realm" consisting of the Forms. Thus, though there is the term "Platonic idealism", this refers to Platonic Ideas or the Forms, and not to some platonic kind of idealism, an 18th-century view which sees matter as unreal in favour of mind. For Plato, though grasped by the mind, only the Forms are truly real.

Plato's Forms thus represent types of things, as well as properties, patterns, and relations, to which we refer as objects. Just as individual tables, chairs, and cars refer to objects in this world, 'tableness', 'chairness', and 'carness', as well as e. g. justice, truth, and beauty refer to objects in another world. One of Plato's most cited examples for the Forms were the truths of geometry, such as the Pythagorean theorem.

In other words, the Forms are universals given as a solution to the problem of universals, or the problem of "the One and the Many", e. g. how one predicate "red" can apply to many red objects. For Plato this is because there is one abstract object or Form of red, redness itself, in which the several red things "participate". As Plato's solution is that universals are Forms and that Forms are real if anything is, Plato's philosophy is unambiguously called Platonic realism. According to Aristotle, Plato's best known argument in support of the Forms was the "one over many" argument.[76]

Aside from being immutable, timeless, changeless, and one over many, the Forms also provide definitions and the standard against which all instances are measured. In the dialogues Socrates regularly asks for the meaning – in the sense of intensional definitions – of a general term (e. g. justice, truth, beauty), and criticizes those who instead give him particular, extensional examples, rather than the quality shared by all examples.

There is thus a world of perfect, eternal, and changeless meanings of predicates, the Forms, existing in the realm of Being outside of space and time; and the imperfect sensible world of becoming, subjects somehow in a state between being and nothing, that partakes of the qualities of the Forms, and is its instantiation.

The soul

Plato advocates a belief in the immortality of the soul, and several dialogues end with long speeches imagining the afterlife. In the Timaeus, Socrates locates the parts of the soul within the human body: Reason is located in the head, spirit in the top third of the torso, and the appetite in the middle third of the torso, down to the navel.[77][78]

Epistemology

Several aspects of epistemology are also discussed by Socrates, such as wisdom. More than one dialogue contrasts knowledge and opinion. Plato's epistemology involves Socrates arguing that knowledge is not empirical, and that it comes from divine insight. The Forms are also responsible for both knowledge or certainty, and are grasped by pure reason.

In several dialogues, Socrates inverts the common man's intuition about what is knowable and what is real. Reality is unavailable to those who use their senses. Socrates says that he who sees with his eyes is blind. While most people take the objects of their senses to be real if anything is, Socrates is contemptuous of people who think that something has to be graspable in the hands to be real. In the Theaetetus, he says such people are eu amousoi (εὖ ἄμουσοι), an expression that means literally, "happily without the muses".[79] In other words, such people are willingly ignorant, living without divine inspiration and access to higher insights about reality.

In Plato's dialogues, Socrates always insists on his ignorance and humility, that he knows nothing, so called Socratic irony. Several dialogues refute a series of viewpoints, but offer no positive position of its own, ending in aporia.

Recollection

In several of Plato's dialogues, Socrates promulgates the idea that knowledge is a matter of recollection of the state before one is born, and not of observation or study.[80] Keeping with the theme of admitting his own ignorance, Socrates regularly complains of his forgetfulness. In the Meno, Socrates uses a geometrical example to expound Plato's view that knowledge in this latter sense is acquired by recollection. Socrates elicits a fact concerning a geometrical construction from a slave boy, who could not have otherwise known the fact (due to the slave boy's lack of education). The knowledge must be present, Socrates concludes, in an eternal, non-experiential form.

In other dialogues, the Sophist, Statesman, Republic, and the Parmenides, Plato himself associates knowledge with the apprehension of unchanging Forms and their relationships to one another (which he calls "expertise" in Dialectic), including through the processes of collection and division.[81] More explicitly, Plato himself argues in the Timaeus that knowledge is always proportionate to the realm from which it is gained. In other words, if one derives one's account of something experientially, because the world of sense is in flux, the views therein attained will be mere opinions. And opinions are characterized by a lack of necessity and stability. On the other hand, if one derives one's account of something by way of the non-sensible forms, because these forms are unchanging, so too is the account derived from them. That apprehension of forms is required for knowledge may be taken to cohere with Plato's theory in the Theaetetus and Meno.[82] Indeed, the apprehension of Forms may be at the base of the "account" required for justification, in that it offers foundational knowledge which itself needs no account, thereby avoiding an infinite regression.[83]

Justified true belief

Many have interpreted Plato as stating—even having been the first to write—that knowledge is justified true belief, an influential view that informed future developments in epistemology.[84] This interpretation is partly based on a reading of the Theaetetus wherein Plato argues that knowledge is distinguished from mere true belief by the knower having an "account" of the object of their true belief.[85] And this theory may again be seen in the Meno, where it is suggested that true belief can be raised to the level of knowledge if it is bound with an account as to the question of "why" the object of the true belief is so.[86][87]

Many years later, Edmund Gettier famously demonstrated the problems of the justified true belief account of knowledge. That the modern theory of justified true belief as knowledge which Gettier addresses is equivalent to Plato's is accepted by some scholars but rejected by others.[88] Plato himself also identified problems with the justified true belief definition in the Theaetetus, concluding that justification (or an "account") would require knowledge of difference, meaning that the definition of knowledge is circular.[89][90]

Ethics

Several dialogues discuss ethics including virtue and vice, pleasure and pain, crime and punishment, and justice and medicine. Plato views "The Good" as the supreme Form, somehow existing even "beyond being".

Socrates propounded a moral intellectualism which claimed nobody does bad on purpose, and to know what is good results in doing what is good; that knowledge is virtue. In the Protagoras dialogue it is argued that virtue is innate and cannot be learned.

Socrates presents the famous Euthyphro dilemma in the dialogue of the same name: "Is the pious (τὸ ὅσιον) loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is loved by the gods?" (10a)

Justice

As above, in the Republic, Plato asks the question, “What is justice?” By means of the Greek term dikaiosune – a term for “justice” that captures both individual justice and the justice that informs societies, Plato is able not only to inform metaphysics, but also ethics and politics with the question: “What is the basis of moral and social obligation?”

Plato's well-known answer rests upon the fundamental responsibility to seek wisdom, wisdom which leads to an understanding of the Form of the Good. Plato further argues that such understanding of forms produces and ensures the good communal life when ideally structured under a philosopher king in a society with three classes (philosophers kings, guardians and workers) that neatly mirror his triadic view of the individual soul (reason, spirit and appetite). In this manner, justice is obtained when knowledge of how to fulfill one's moral and political function in society is put into practice.[91]

Politics

The dialogues also discuss politics. Some of Plato's most famous doctrines are contained in the Republic as well as in the Laws and the Statesman. Because these doctrines are not spoken directly by Plato and vary between dialogues, they cannot be straightforwardly assumed as representing Plato's own views.

Socrates asserts that societies have a tripartite class structure corresponding to the appetite/spirit/reason structure of the individual soul. The appetite/spirit/reason are analogous to the castes of society.[92]

- Productive (Workers) – the labourers, carpenters, plumbers, masons, merchants, farmers, ranchers, etc. These correspond to the "appetite" part of the soul.

- Protective (Warriors or Guardians) – those who are adventurous, strong and brave; in the armed forces. These correspond to the "spirit" part of the soul.

- Governing (Rulers or Philosopher Kings) – those who are intelligent, rational, self-controlled, in love with wisdom, well suited to make decisions for the community. These correspond to the "reason" part of the soul and are very few.

According to this model, the principles of Athenian democracy (as it existed in his day) are rejected as only a few are fit to rule. Instead of rhetoric and persuasion, Socrates says reason and wisdom should govern. As Socrates puts it:

- "Until philosophers rule as kings or those who are now called kings and leading men genuinely and adequately philosophize, that is, until political power and philosophy entirely coincide, while the many natures who at present pursue either one exclusively are forcibly prevented from doing so, cities will have no rest from evils,... nor, I think, will the human race."[93]

Socrates describes these "philosopher kings" as "those who love the sight of truth"[94] and supports the idea with the analogy of a captain and his ship or a doctor and his medicine. According to him, sailing and health are not things that everyone is qualified to practice by nature. A large part of the Republic then addresses how the educational system should be set up to produce these philosopher kings.

In addition, the ideal city is used as an image to illuminate the state of one's soul, or the will, reason, and desires combined in the human body. Socrates is attempting to make an image of a rightly ordered human, and then later goes on to describe the different kinds of humans that can be observed, from tyrants to lovers of money in various kinds of cities. The ideal city is not promoted, but only used to magnify the different kinds of individual humans and the state of their soul. However, the philosopher king image was used by many after Plato to justify their personal political beliefs. The philosophic soul according to Socrates has reason, will, and desires united in virtuous harmony. A philosopher has the moderate love for wisdom and the courage to act according to wisdom. Wisdom is knowledge about the Good or the right relations between all that exists.

Wherein it concerns states and rulers, Socrates asks which is better—a bad democracy or a country reigned by a tyrant. He argues that it is better to be ruled by a bad tyrant, than by a bad democracy (since here all the people are now responsible for such actions, rather than one individual committing many bad deeds.) This is emphasised within the Republic as Socrates describes the event of mutiny on board a ship.[95] Socrates suggests the ship's crew to be in line with the democratic rule of many and the captain, although inhibited through ailments, the tyrant. Socrates' description of this event is parallel to that of democracy within the state and the inherent problems that arise.

According to Socrates, a state made up of different kinds of souls will, overall, decline from an aristocracy (rule by the best) to a timocracy (rule by the honourable), then to an oligarchy (rule by the few), then to a democracy (rule by the people), and finally to tyranny (rule by one person, rule by a tyrant).[96] Aristocracy in the sense of government (politeia) is advocated in Plato's Republic. This regime is ruled by a philosopher king, and thus is grounded on wisdom and reason.

The aristocratic state, and the man whose nature corresponds to it, are the objects of Plato's analyses throughout much of the Republic, as opposed to the other four types of states/men, who are discussed later in his work. In Book VIII, Socrates states in order the other four imperfect societies with a description of the state's structure and individual character. In timocracy the ruling class is made up primarily of those with a warrior-like character.[97] Oligarchy is made up of a society in which wealth is the criterion of merit and the wealthy are in control.[98] In democracy, the state bears resemblance to ancient Athens with traits such as equality of political opportunity and freedom for the individual to do as he likes.[99] Democracy then degenerates into tyranny from the conflict of rich and poor. It is characterized by an undisciplined society existing in chaos, where the tyrant rises as popular champion leading to the formation of his private army and the growth of oppression.[100][96][101]

Art and poetry

Several dialogues tackle questions about art, including rhetoric and rhapsody. Socrates says that poetry is inspired by the muses, and is not rational. He speaks approvingly of this, and other forms of divine madness (drunkenness, eroticism, and dreaming) in the Phaedrus,[102] and yet in the Republic wants to outlaw Homer's great poetry, and laughter as well. In Ion, Socrates gives no hint of the disapproval of Homer that he expresses in the Republic. The dialogue Ion suggests that Homer's Iliad functioned in the ancient Greek world as the Bible does today in the modern Christian world: as divinely inspired literature that can provide moral guidance, if only it can be properly interpreted.

Unwritten doctrines

For a long time, Plato's unwritten doctrines[103][104][105] had been controversial. Many modern books on Plato seem to diminish its importance; nevertheless, the first important witness who mentions its existence is Aristotle, who in his Physics writes: "It is true, indeed, that the account he gives there [i.e. in Timaeus] of the participant is different from what he says in his so-called unwritten teachings (ἄγραφα δόγματα)."[106] The term "ἄγραφα δόγματα" literally means unwritten doctrines or unwritten dogmas and it stands for the most fundamental metaphysical teaching of Plato, which he disclosed only orally, and some say only to his most trusted fellows, and which he may have kept secret from the public. The importance of the unwritten doctrines does not seem to have been seriously questioned before the 19th century.

A reason for not revealing it to everyone is partially discussed in Phaedrus where Plato criticizes the written transmission of knowledge as faulty, favouring instead the spoken logos: "he who has knowledge of the just and the good and beautiful ... will not, when in earnest, write them in ink, sowing them through a pen with words, which cannot defend themselves by argument and cannot teach the truth effectually."[107] The same argument is repeated in Plato's Seventh Letter: "every serious man in dealing with really serious subjects carefully avoids writing."[108] In the same letter he writes: "I can certainly declare concerning all these writers who claim to know the subjects that I seriously study ... there does not exist, nor will there ever exist, any treatise of mine dealing therewith."[109] Such secrecy is necessary in order not "to expose them to unseemly and degrading treatment".[110]

It is, however, said that Plato once disclosed this knowledge to the public in his lecture On the Good (Περὶ τἀγαθοῦ), in which the Good (τὸ ἀγαθόν) is identified with the One (the Unity, τὸ ἕν), the fundamental ontological principle. The content of this lecture has been transmitted by several witnesses. Aristoxenus describes the event in the following words: "Each came expecting to learn something about the things that are generally considered good for men, such as wealth, good health, physical strength, and altogether a kind of wonderful happiness. But when the mathematical demonstrations came, including numbers, geometrical figures and astronomy, and finally the statement Good is One seemed to them, I imagine, utterly unexpected and strange; hence some belittled the matter, while others rejected it."[111] Simplicius quotes Alexander of Aphrodisias, who states that "according to Plato, the first principles of everything, including the Forms themselves are One and Indefinite Duality (ἡ ἀόριστος δυάς), which he called Large and Small (τὸ μέγα καὶ τὸ μικρόν)", and Simplicius reports as well that "one might also learn this from Speusippus and Xenocrates and the others who were present at Plato's lecture on the Good".[44]

Their account is in full agreement with Aristotle's description of Plato's metaphysical doctrine. In Metaphysics he writes: "Now since the Forms are the causes of everything else, he [i.e. Plato] supposed that their elements are the elements of all things. Accordingly the material principle is the Great and Small [i.e. the Dyad], and the essence is the One (τὸ ἕν), since the numbers are derived from the Great and Small by participation in the One".[112] "From this account it is clear that he only employed two causes: that of the essence, and the material cause; for the Forms are the cause of the essence in everything else, and the One is the cause of it in the Forms. He also tells us what the material substrate is of which the Forms are predicated in the case of sensible things, and the One in that of the Forms—that it is this the duality (the Dyad, ἡ δυάς), the Great and Small (τὸ μέγα καὶ τὸ μικρόν). Further, he assigned to these two elements respectively the causation of good and of evil".[112]

The most important aspect of this interpretation of Plato's metaphysics is the continuity between his teaching and the Neoplatonic interpretation of Plotinus[i] or Ficino[j] which has been considered erroneous by many but may in fact have been directly influenced by oral transmission of Plato's doctrine. A modern scholar who recognized the importance of the unwritten doctrine of Plato was Heinrich Gomperz who described it in his speech during the 7th International Congress of Philosophy in 1930.[113] All the sources related to the ἄγραφα δόγματα have been collected by Konrad Gaiser and published as Testimonia Platonica.[114] These sources have subsequently been interpreted by scholars from the German Tübingen School of interpretation such as Hans Joachim Krämer or Thomas A. Szlezák.[k]

Themes of Plato's dialogues

Trial of Socrates

The trial of Socrates and his death sentence is the central, unifying event of Plato's dialogues. It is relayed in the dialogues Apology, Crito, and Phaedo. Apology is Socrates' defence speech, and Crito and Phaedo take place in prison after the conviction.

Apology is among the most frequently read of Plato's works. In the Apology, Socrates tries to dismiss rumours that he is a sophist and defends himself against charges of disbelief in the gods and corruption of the young. Socrates insists that long-standing slander will be the real cause of his demise, and says the legal charges are essentially false. Socrates famously denies being wise, and explains how his life as a philosopher was launched by the Oracle at Delphi. He says that his quest to resolve the riddle of the oracle put him at odds with his fellow man, and that this is the reason he has been mistaken for a menace to the city-state of Athens.

In Apology, Socrates is presented as mentioning Plato by name as one of those youths close enough to him to have been corrupted, if he were in fact guilty of corrupting the youth, and questioning why their fathers and brothers did not step forward to testify against him if he was indeed guilty of such a crime.[115] Later, Plato is mentioned along with Crito, Critobolus, and Apollodorus as offering to pay a fine of 30 minas on Socrates' behalf, in lieu of the death penalty proposed by Meletus.[116] In the Phaedo, the title character lists those who were in attendance at the prison on Socrates' last day, explaining Plato's absence by saying, "Plato was ill".[117]

The trial in other dialogues

If Plato's important dialogues do not refer to Socrates' execution explicitly, they allude to it, or use characters or themes that play a part in it. Five dialogues foreshadow the trial: In the Theaetetus and the Euthyphro Socrates tells people that he is about to face corruption charges.[118][119] In the Meno, one of the men who brings legal charges against Socrates, Anytus, warns him about the trouble he may get into if he does not stop criticizing important people.[120] In the Gorgias, Socrates says that his trial will be like a doctor prosecuted by a cook who asks a jury of children to choose between the doctor's bitter medicine and the cook's tasty treats.[121] In the Republic, Socrates explains why an enlightened man (presumably himself) will stumble in a courtroom situation.[122] Plato's support of aristocracy and distrust of democracy is also taken to be partly rooted in a democracy having killed Socrates. In the Protagoras, Socrates is a guest at the home of Callias, son of Hipponicus, a man whom Socrates disparages in the Apology as having wasted a great amount of money on sophists' fees.

Two other important dialogues, the Symposium and the Phaedrus, are linked to the main storyline by characters. In the Apology, Socrates says Aristophanes slandered him in a comic play, and blames him for causing his bad reputation, and ultimately, his death.[123] In the Symposium, the two of them are drinking together with other friends. The character Phaedrus is linked to the main story line by character (Phaedrus is also a participant in the Symposium and the Protagoras) and by theme (the philosopher as divine emissary, etc.) The Protagoras is also strongly linked to the Symposium by characters: all of the formal speakers at the Symposium (with the exception of Aristophanes) are present at the home of Callias in that dialogue. Charmides and his guardian Critias are present for the discussion in the Protagoras. Examples of characters crossing between dialogues can be further multiplied. The Protagoras contains the largest gathering of Socratic associates.

In the dialogues Plato is most celebrated and admired for, Socrates is concerned with human and political virtue, has a distinctive personality, and friends and enemies who "travel" with him from dialogue to dialogue. This is not to say that Socrates is consistent: a man who is his friend in one dialogue may be an adversary or subject of his mockery in another. For example, Socrates praises the wisdom of Euthyphro many times in the Cratylus, but makes him look like a fool in the Euthyphro. He disparages sophists generally, and Prodicus specifically in the Apology, whom he also slyly jabs in the Cratylus for charging the hefty fee of fifty drachmas for a course on language and grammar. However, Socrates tells Theaetetus in his namesake dialogue that he admires Prodicus and has directed many pupils to him. Socrates' ideas are also not consistent within or between or among dialogues.

Allegories

Mythos and logos are terms that evolved along classical Greek history. In the times of Homer and Hesiod (8th century BC) they were essentially synonyms, and contained the meaning of 'tale' or 'history'. Later came historians like Herodotus and Thucydides, as well as philosophers like Heraclitus and Parmenides and other Presocratics who introduced a distinction between both terms; mythos became more a nonverifiable account, and logos a rational account.[124] It may seem that Plato, being a disciple of Socrates and a strong partisan of philosophy based on logos, should have avoided the use of myth-telling. Instead he made an abundant use of it. This fact has produced analytical and interpretative work, in order to clarify the reasons and purposes for that use.

Plato, in general, distinguished between three types of myth.[l] First there were the false myths, like those based on stories of gods subject to passions and sufferings, because reason teaches that God is perfect. Then came the myths based on true reasoning, and therefore also true. Finally there were those non verifiable because beyond of human reason, but containing some truth in them. Regarding the subjects of Plato's myths they are of two types, those dealing with the origin of the universe, and those about morals and the origin and fate of the soul.[125]

It is generally agreed that the main purpose for Plato in using myths was didactic. He considered that only a few people were capable or interested in following a reasoned philosophical discourse, but men in general are attracted by stories and tales. Consequently, then, he used the myth to convey the conclusions of the philosophical reasoning. Some of Plato's myths were based in traditional ones, others were modifications of them, and finally he also invented altogether new myths.[126] Notable examples include the story of Atlantis, the Myth of Er, and the Allegory of the Cave.

The Cave

The theory of Forms is most famously captured in his Allegory of the Cave, and more explicitly in his analogy of the sun and the divided line. The Allegory of the Cave is a paradoxical analogy wherein Socrates argues that the invisible world is the most intelligible ('noeton') and that the visible world ((h)oraton) is the least knowable, and the most obscure.

Socrates says in the Republic that people who take the sun-lit world of the senses to be good and real are living pitifully in a den of evil and ignorance. Socrates admits that few climb out of the den, or cave of ignorance, and those who do, not only have a terrible struggle to attain the heights, but when they go back down for a visit or to help other people up, they find themselves objects of scorn and ridicule.

According to Socrates, physical objects and physical events are "shadows" of their ideal or perfect forms, and exist only to the extent that they instantiate the perfect versions of themselves. Just as shadows are temporary, inconsequential epiphenomena produced by physical objects, physical objects are themselves fleeting phenomena caused by more substantial causes, the ideals of which they are mere instances. For example, Socrates thinks that perfect justice exists (although it is not clear where) and his own trial would be a cheap copy of it.

The Allegory of the Cave is intimately connected to his political ideology, that only people who have climbed out of the cave and cast their eyes on a vision of goodness are fit to rule. Socrates claims that the enlightened men of society must be forced from their divine contemplation and be compelled to run the city according to their lofty insights. Thus is born the idea of the "philosopher-king", the wise person who accepts the power thrust upon him by the people who are wise enough to choose a good master. This is the main thesis of Socrates in the Republic, that the most wisdom the masses can muster is the wise choice of a ruler.[127]

Ring of Gyges

A ring which could make one invisible, the Ring of Gyges is proposed in the Republic by the character of Glaucon, and considered by the rest of characters for its ethical consequences, whether an individual possessing it would be most happy abstaining or doing injustice.

Chariot

He also compares the soul (psyche) to a chariot. In this allegory he introduces a triple soul which composed of a charioteer and two horses. The charioteer is a symbol of intellectual and logical part of the soul (logistikon), and two horses represents the moral virtues (thymoeides) and passionate instincts (epithymetikon), respectively, to illustrate the conflict between them.

Dialectic

Socrates employs a dialectic method which proceeds by questioning. The role of dialectic in Plato's thought is contested but there are two main interpretations: a type of reasoning and a method of intuition.[128] Simon Blackburn adopts the first, saying that Plato's dialectic is "the process of eliciting the truth by means of questions aimed at opening out what is already implicitly known, or at exposing the contradictions and muddles of an opponent's position."[128] A similar interpretation has been put forth by Louis Hartz, who suggests that elements of the dialectic are borrowed from Hegel.[129] According to this view, opposing arguments improve upon each other, and prevailing opinion is shaped by the synthesis of many conflicting ideas over time. Each new idea exposes a flaw in the accepted model, and the epistemological substance of the debate continually approaches the truth. Hartz's is a teleological interpretation at the core, in which philosophers will ultimately exhaust the available body of knowledge and thus reach "the end of history." Karl Popper, on the other hand, claims that dialectic is the art of intuition for "visualising the divine originals, the Forms or Ideas, of unveiling the Great Mystery behind the common man's everyday world of appearances."[130]

Family

Plato often discusses the father-son relationship and the question of whether a father's interest in his sons has much to do with how well his sons turn out. In ancient Athens, a boy was socially located by his family identity, and Plato often refers to his characters in terms of their paternal and fraternal relationships. Socrates was not a family man, and saw himself as the son of his mother, who was apparently a midwife. A divine fatalist, Socrates mocks men who spent exorbitant fees on tutors and trainers for their sons, and repeatedly ventures the idea that good character is a gift from the gods. Plato's dialogue Crito reminds Socrates that orphans are at the mercy of chance, but Socrates is unconcerned. In the Theaetetus, he is found recruiting as a disciple a young man whose inheritance has been squandered. Socrates twice compares the relationship of the older man and his boy lover to the father-son relationship,[131][132] and in the Phaedo, Socrates' disciples, towards whom he displays more concern than his biological sons, say they will feel "fatherless" when he is gone.

Though Plato agreed with Aristotle that women were inferior to men, in the fourth book of the Republic the character of Socrates says this was only because of nomos or custom and not because of nature, and thus women needed paidia, rearing or education to be equal to men. In the "merely probable tale" of the eponymous character in the Timaeus, unjust men who live corrupted lives would be reincarnated as women or various animal kinds.

Narration

Plato never presents himself as a participant in any of the dialogues, and with the exception of the Apology, there is no suggestion that he heard any of the dialogues firsthand. Some dialogues have no narrator but have a pure "dramatic" form (examples: Meno, Gorgias, Phaedrus, Crito, Euthyphro), some dialogues are narrated by Socrates, wherein he speaks in first person (examples: Lysis, Charmides, Republic). One dialogue, Protagoras, begins in dramatic form but quickly proceeds to Socrates' narration of a conversation he had previously with the sophist for whom the dialogue is named; this narration continues uninterrupted till the dialogue's end.

Two dialogues Phaedo and Symposium also begin in dramatic form but then proceed to virtually uninterrupted narration by followers of Socrates. Phaedo, an account of Socrates' final conversation and hemlock drinking, is narrated by Phaedo to Echecrates in a foreign city not long after the execution took place.[m] The Symposium is narrated by Apollodorus, a Socratic disciple, apparently to Glaucon. Apollodorus assures his listener that he is recounting the story, which took place when he himself was an infant, not from his own memory, but as remembered by Aristodemus, who told him the story years ago.

The Theaetetus is a peculiar case: a dialogue in dramatic form embedded within another dialogue in dramatic form. In the beginning of the Theaetetus,[134] Euclides says that he compiled the conversation from notes he took based on what Socrates told him of his conversation with the title character. The rest of the Theaetetus is presented as a "book" written in dramatic form and read by one of Euclides' slaves.[135] Some scholars take this as an indication that Plato had by this date wearied of the narrated form.[136] With the exception of the Theaetetus, Plato gives no explicit indication as to how these orally transmitted conversations came to be written down.

History of Plato's dialogues

Thirty-five dialogues and thirteen letters (the Epistles) have traditionally been ascribed to Plato, though modern scholarship doubts the authenticity of at least some of these. Plato's writings have been published in several fashions; this has led to several conventions regarding the naming and referencing of Plato's texts.

The usual system for making unique references to sections of the text by Plato derives from a 16th-century edition of Plato's works by Henricus Stephanus known as Stephanus pagination.

One tradition regarding the arrangement of Plato's texts is according to tetralogies. This scheme is ascribed by Diogenes Laërtius to an ancient scholar and court astrologer to Tiberius named Thrasyllus.

Chronology

No one knows the exact order Plato's dialogues were written in, nor the extent to which some might have been later revised and rewritten. The works are usually grouped into Early (sometimes by some into Transitional), Middle, and Late period.[137][138] This choice to group chronologically is thought worthy of criticism by some (Cooper et al),[139] given that it is recognized that there is no absolute agreement as to the true chronology, since the facts of the temporal order of writing are not confidently ascertained.[140] Chronology was not a consideration in ancient times, in that groupings of this nature are virtually absent (Tarrant) in the extant writings of ancient Platonists.[141]

Whereas those classified as "early dialogues" often conclude in aporia, the so-called "middle dialogues" provide more clearly stated positive teachings that are often ascribed to Plato such as the theory of Forms. The remaining dialogues are classified as "late" and are generally agreed to be difficult and challenging pieces of philosophy. This grouping is the only one proven by stylometric analysis.[142] Among those who classify the dialogues into periods of composition, Socrates figures in all of the "early dialogues" and they are considered the most faithful representations of the historical Socrates.[143]

The following represents one relatively common division.[144] It should, however, be kept in mind that many of the positions in the ordering are still highly disputed, and also that the very notion that Plato's dialogues can or should be "ordered" is by no means universally accepted. Increasingly in the most recent Plato scholarship, writers are sceptical of the notion that the order of Plato's writings can be established with any precision,[145] though Plato's works are still often characterized as falling at least roughly into three groups.[6]

Early: Apology, Charmides, Crito, Euthyphro, Gorgias, (Lesser) Hippias (minor), (Greater) Hippias (major), Ion, Laches, Lysis, Protagoras

Middle: Cratylus, Euthydemus, Meno, Parmenides, Phaedo, Phaedrus, Republic, Symposium, Theaetetus

Late: Critias, Sophist, Statesman / Politicus, Timaeus, Philebus, Laws.[143]

A significant distinction of the early Plato and the later Plato has been offered by scholars such as E.R. Dodds and has been summarized by Harold Bloom in his book titled Agon: "E.R. Dodds is the classical scholar whose writings most illuminated the Hellenic descent (in) The Greeks and the Irrational ... In his chapter on Plato and the Irrational Soul ... Dodds traces Plato's spiritual evolution from the pure rationalist of the Protagoras to the transcendental psychologist, influenced by the Pythagoreans and Orphics, of the later works culminating in the Laws."[146]

Lewis Campbell was the first[147] to make exhaustive use of stylometry to prove the great probability that the Critias, Timaeus, Laws, Philebus, Sophist, and Statesman were all clustered together as a group, while the Parmenides, Phaedrus, Republic, and Theaetetus belong to a separate group, which must be earlier (given Aristotle's statement in his Politics[148] that the Laws was written after the Republic; cf. Diogenes Laërtius Lives 3.37). What is remarkable about Campbell's conclusions is that, in spite of all the stylometric studies that have been conducted since his time, perhaps the only chronological fact about Plato's works that can now be said to be proven by stylometry is the fact that Critias, Timaeus, Laws, Philebus, Sophist, and Statesman are the latest of Plato's dialogues, the others earlier.[142]

Protagoras is often considered one of the last of the "early dialogues". Three dialogues are often considered "transitional" or "pre-middle": Euthydemus, Gorgias, and Meno. Proponents of dividing the dialogues into periods often consider the Parmenides and Theaetetus to come late in the middle period and be transitional to the next, as they seem to treat the theory of Forms critically (Parmenides) or only indirectly (Theaetetus).[149] Ritter's stylometric analysis places Phaedrus as probably after Theaetetus and Parmenides,[150] although it does not relate to the theory of Forms in the same way. The first book of the Republic is often thought to have been written significantly earlier than the rest of the work, although possibly having undergone revisions when the later books were attached to it.[149]

While looked to for Plato's "mature" answers to the questions posed by his earlier works, those answers are difficult to discern. Some scholars[143] indicate that the theory of Forms is absent from the late dialogues, its having been refuted in the Parmenides, but there isn't total consensus that the Parmenides actually refutes the theory of Forms.[151]

Writings of doubted authenticity

Jowett mentions in his Appendix to Menexenus, that works which bore the character of a writer were attributed to that writer even when the actual author was unknown.[152]

For below:

(*) if there is no consensus among scholars as to whether Plato is the author, and (‡) if most scholars agree that Plato is not the author of the work.[153]

First Alcibiades (*), Second Alcibiades (‡), Clitophon (*), Epinomis (‡), Epistles (*), Hipparchus (‡), Menexenus (*), Minos (‡), (Rival) Lovers (‡), Theages (‡)

Spurious writings

The following works were transmitted under Plato's name, most of them already considered spurious in antiquity, and so were not included by Thrasyllus in his tetralogical arrangement. These works are labelled as Notheuomenoi ("spurious") or Apocrypha.

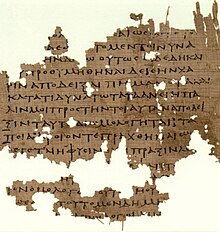

Textual sources and history

Some 250 known manuscripts of Plato survive.[154] The texts of Plato as received today apparently represent the complete written philosophical work of Plato and are generally good by the standards of textual criticism.[155] No modern edition of Plato in the original Greek represents a single source, but rather it is reconstructed from multiple sources which are compared with each other. These sources are medieval manuscripts written on vellum (mainly from 9th to 13th century AD Byzantium), papyri (mainly from late antiquity in Egypt), and from the independent testimonia of other authors who quote various segments of the works (which come from a variety of sources). The text as presented is usually not much different from what appears in the Byzantine manuscripts, and papyri and testimonia just confirm the manuscript tradition. In some editions however the readings in the papyri or testimonia are favoured in some places by the editing critic of the text. Reviewing editions of papyri for the Republic in 1987, Slings suggests that the use of papyri is hampered due to some poor editing practices.[156]

In the first century AD, Thrasyllus of Mendes had compiled and published the works of Plato in the original Greek, both genuine and spurious. While it has not survived to the present day, all the extant medieval Greek manuscripts are based on his edition.[157]

The oldest surviving complete manuscript for many of the dialogues is the Clarke Plato (Codex Oxoniensis Clarkianus 39, or Codex Boleianus MS E.D. Clarke 39), which was written in Constantinople in 895 and acquired by Oxford University in 1809.[158] The Clarke is given the siglum B in modern editions. B contains the first six tetralogies and is described internally as being written by "John the Calligrapher" on behalf of Arethas of Caesarea. It appears to have undergone corrections by Arethas himself.[159] For the last two tetralogies and the apocrypha, the oldest surviving complete manuscript is Codex Parisinus graecus 1807, designated A, which was written nearly contemporaneously to B, circa 900 AD.[160] A must be a copy of the edition edited by the patriarch, Photios, teacher of Arethas.[161][162][163]A probably had an initial volume containing the first 7 tetralogies which is now lost, but of which a copy was made, Codex Venetus append. class. 4, 1, which has the siglum T. The oldest manuscript for the seventh tetralogy is Codex Vindobonensis 54. suppl. phil. Gr. 7, with siglum W, with a supposed date in the twelfth century.[164] In total there are fifty-one such Byzantine manuscripts known, while others may yet be found.[165]

To help establish the text, the older evidence of papyri and the independent evidence of the testimony of commentators and other authors (i.e., those who quote and refer to an old text of Plato which is no longer extant) are also used. Many papyri which contain fragments of Plato's texts are among the Oxyrhynchus Papyri. The 2003 Oxford Classical Texts edition by Slings even cites the Coptic translation of a fragment of the Republic in the Nag Hammadi library as evidence.[166] Important authors for testimony include Olympiodorus the Younger, Plutarch, Proclus, Iamblichus, Eusebius, and Stobaeus.

During the early Renaissance, the Greek language and, along with it, Plato's texts were reintroduced to Western Europe by Byzantine scholars. In September or October 1484 Filippo Valori and Francesco Berlinghieri printed 1025 copies of Ficino's translation, using the printing press at the Dominican convent S.Jacopo di Ripoli.[167][168] Cosimo had been influenced toward studying Plato by the many Byzantine Platonists in Florence during his day, including George Gemistus Plethon.

The 1578 edition[169] of Plato's complete works published by Henricus Stephanus (Henri Estienne) in Geneva also included parallel Latin translation and running commentary by Joannes Serranus (Jean de Serres). It was this edition which established standard Stephanus pagination, still in use today.[170]

Modern editions

The Oxford Classical Texts offers the current standard complete Greek text of Plato's complete works. In five volumes edited by John Burnet, its first edition was published 1900–1907, and it is still available from the publisher, having last been printed in 1993.[171][172] The second edition is still in progress with only the first volume, printed in 1995, and the Republic, printed in 2003, available. The Cambridge Greek and Latin Texts and Cambridge Classical Texts and Commentaries series includes Greek editions of the Protagoras, Symposium, Phaedrus, Alcibiades, and Clitophon, with English philological, literary, and, to an extent, philosophical commentary.[173][174] One distinguished edition of the Greek text is E. R. Dodds' of the Gorgias, which includes extensive English commentary.[175][176]

The modern standard complete English edition is the 1997 Hackett Plato, Complete Works, edited by John M. Cooper.[177][178] For many of these translations Hackett offers separate volumes which include more by way of commentary, notes, and introductory material. There is also the Clarendon Plato Series by Oxford University Press which offers English translations and thorough philosophical commentary by leading scholars on a few of Plato's works, including John McDowell's version of the Theaetetus.[179] Cornell University Press has also begun the Agora series of English translations of classical and medieval philosophical texts, including a few of Plato's.[180]

Criticism

The most famous criticism of the Theory of Forms is the Third Man Argument by Aristotle in the Metaphysics. Plato had actually already considered this objection with the idea of "large" rather than "man" in the dialogue Parmenides, using the elderly Elean philosophers Parmenides and Zeno characters anachronistically to criticize the character of the younger Socrates who proposed the idea. The dialogue ends in aporia.

Many recent philosophers have diverged from what some would describe as the ontological models and moral ideals characteristic of traditional Platonism. A number of these postmodern philosophers have thus appeared to disparage Platonism from more or less informed perspectives. Friedrich Nietzsche notoriously attacked Plato's "idea of the good itself" along with many fundamentals of Christian morality, which he interpreted as "Platonism for the masses" in one of his most important works, Beyond Good and Evil (1886). Martin Heidegger argued against Plato's alleged obfuscation of Being in his incomplete tome, Being and Time (1927), and the philosopher of science Karl Popper argued in The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945) that Plato's alleged proposal for a utopian political regime in the Republic was prototypically totalitarian.

The Dutch historian of science Eduard Jan Dijksterhuis criticizes Plato, stating that he was guilty of "constructing an imaginary nature by reasoning from preconceived principles and forcing reality more or less to adapt itself to this construction."[181] Dijksterhuis adds that one of the errors into which Plato had "fallen in an almost grotesque manner, consisted in an over-estimation of what unaided thought, i.e. without recourse to experience, could achieve in the field of natural science."[182]

Legacy

In the arts

Plato's Academy mosaic was created in the villa of T. Siminius Stephanus in Pompeii, around 100 BC to 100 CE. The School of Athens fresco by Raphael features Plato also as a central figure. The Nuremberg Chronicle depicts Plato and other as anachronistic schoolmen.

In philosophy

Plato's thought is often compared with that of his most famous student, Aristotle, whose reputation during the Western Middle Ages so completely eclipsed that of Plato that the Scholastic philosophers referred to Aristotle as "the Philosopher". However, in the Byzantine Empire, the study of Plato continued.

The only Platonic work known to western scholarship was Timaeus, until translations were made after the fall of Constantinople, which occurred during 1453.[183] George Gemistos Plethon brought Plato's original writings from Constantinople in the century of its fall. It is believed that Plethon passed a copy of the Dialogues to Cosimo de' Medici when in 1438 the Council of Ferrara, called to unify the Greek and Latin Churches, was adjourned to Florence, where Plethon then lectured on the relation and differences of Plato and Aristotle, and fired Cosimo with his enthusiasm;[184] Cosimo would supply Marsilio Ficino with Plato's text for translation to Latin. During the early Islamic era, Persian and Arab scholars translated much of Plato into Arabic and wrote commentaries and interpretations on Plato's, Aristotle's and other Platonist philosophers' works (see Al-Farabi, Avicenna, Averroes, Hunayn ibn Ishaq). Many of these commentaries on Plato were translated from Arabic into Latin and as such influenced Medieval scholastic philosophers.[185]

During the Renaissance, with the general resurgence of interest in classical civilization, knowledge of Plato's philosophy would become widespread again in the West. Many of the greatest early modern scientists and artists who broke with Scholasticism and fostered the flowering of the Renaissance, with the support of the Plato-inspired Lorenzo (grandson of Cosimo), saw Plato's philosophy as the basis for progress in the arts and sciences. More problematic was Plato's belief in metempsychosis as well as his ethical views (on polyamory and euthanasia in particular), which did not match those of Christianity. It was Plethon's student Bessarion who reconciled Plato with Christian theology, arguing that Plato's views were only ideals, unattainable due to the fall of man.[186] The Cambridge Platonists were around in the 17th century.

By the 19th century, Plato's reputation was restored, and at least on par with Aristotle's. Notable Western philosophers have continued to draw upon Plato's work since that time. Plato's influence has been especially strong in mathematics and the sciences. Plato's resurgence further inspired some of the greatest advances in logic since Aristotle, primarily through Gottlob Frege and his followers Kurt Gödel, Alonzo Church, and Alfred Tarski. Albert Einstein suggested that the scientist who takes philosophy seriously would have to avoid systematization and take on many different roles, and possibly appear as a Platonist or Pythagorean, in that such a one would have "the viewpoint of logical simplicity as an indispensable and effective tool of his research."[187]

The political philosopher and professor Leo Strauss is considered by some as the prime thinker involved in the recovery of Platonic thought in its more political, and less metaphysical, form. Strauss' political approach was in part inspired by the appropriation of Plato and Aristotle by medieval Jewish and Islamic political philosophers, especially Maimonides and Al-Farabi, as opposed to the Christian metaphysical tradition that developed from Neoplatonism. Deeply influenced by Nietzsche and Heidegger, Strauss nonetheless rejects their condemnation of Plato and looks to the dialogues for a solution to what all three latter day thinkers acknowledge as 'the crisis of the West.[citation needed]

W. V. O. Quine dubbed the problem of negative existentials "Plato's beard". Noam Chomsky dubbed the problem of knowledge Plato's problem. One author calls the definist fallacy the Socratic fallacy[188].[relevant? ]

More broadly, platonism (sometimes distinguished from Plato's particular view by the lowercase) refers to the view that there are many abstract objects. Still to this day, platonists take number and the truths of mathematics as the best support in favour of this view. Most mathematicians think, like platonists, that numbers and the truths of mathematics are perceived by reason rather than the senses yet exist independently of minds and people, that is to say, they are discovered rather than invented.[citation needed]

Contemporary platonism is also more open to the idea of there being infinitely many abstract objects, as numbers or propositions might qualify as abstract objects, while ancient Platonism seemed to resist this view, possibly because of the need to overcome the problem of "the One and the Many". Thus e. g. in the Parmenides dialogue, Plato denies there are Forms for more mundane things like hair and mud. However, he repeatedly does support the idea that there are Forms of artifacts, e. g. the Form of Bed. Contemporary platonism also tends to view abstract objects as unable to cause anything, but it is unclear whether the ancient Platonists felt this way.[citation needed]

See also

| Library resources about Plato |

| By Plato |

|---|

Philosophy

- Socratic Problem

- Platonic Academy

- Plato's unwritten doctrines

- List of speakers in Plato's dialogues

- Commentaries on Plato

- Neoplatonism

- Academic Skepticism

Ancient scholars

- Philip of Opus, Plato's amanuensis

- Speusippus, Plato's nephew and the second scholarch of the academy

- Menedemus of Pyrrha

- Xenocrates

- Crantor

- Polemon

- Crates of Athens

- Arcesilaus

- Carneades

- Plotinus, founder of Neoplatonism, although he had no connection to the previous Academy of Plato

- Proclus

- Ammonius Saccas

- Yahya Ibn al-Batriq, Syrian scholar and associate of Al-Kindi who translated Timaeus into Arabic

- Hunayn ibn Ishaq, Arab scholar who either amended or surpassed the Timaeus of al-Batriq and translated Plato's Republic and Laws into Arabic

- Ishaq ibn Hunayn, translated Plato's Sophist with the commentary of Olympiodorus the Younger

- Yahya ibn Adi, translated Laws into Arabic

- Al-Farabi, author of a commentary on Plato's political philosophy

- Averroes, author of a commentary on the Republic

- Marsilio Ficino, Italian scholar and first translator of Plato's complete works into Latin

- Stephanus pagination, the standard reference numbering in Platonic scholarship, based on the 1578 complete Latin translation by Jean de Serres, and published by Henri Estienne

Modern scholars

- Johann Gottfried Stallbaum, major Plato scholar and commentator in Latin

- Eduard Zeller, scholar and classicist

- John Alexander Stewart, major Plato scholar and classicist

- Victor Cousin, scholar and the first translator Plato's complete works into French

- Émile Saisset, scholar and a translator Plato's complete works into French

- Émile Chambry, scholar and a translator Plato's complete works into French

- Otto Apelt, scholar and the first translator Plato's complete works into German

- Benjamin Jowett, scholar and the first translated Plato's complete works into English

- James Adam, major Plato scholar and author of the authoritative critical edition of the Republic

- John Burnet, major Plato scholar and translator

- Francis Macdonald Cornford, translator of Republic and author of commentaries

- William Keith Chambers Guthrie, classical scholar and historian

- E. R. Dodds, classical scholar and author of commentaries on Plato

- Allan Bloom, major Plato scholar and translator of Republic in English

- Myles Burnyeat, major Plato scholar

- Harold F. Cherniss, major Plato scholar

- Guy Cromwell Field, Plato scholar

- Paul Friedländer, Plato scholar

- Terence Irwin, major Plato scholar

- Richard Kraut, major Plato scholar

- Ellen Francis Mason, translator of Plato

- Eric Havelock, Plato scholar

- Alexander Nehamas, major Plato scholar

- Thomas Pangle, major Plato scholar and translator of Laws in English

- Friedrich Schleiermacher, commentator

- Paul Shorey, major Plato scholar and translator of Republic

- John Madison Cooper, major Plato scholar and translator of several works of Plato, and editor of the Hackett edition of the complete works of Plato in English

- Leo Strauss, major Plato scholar

- Seth Benardete, major Plato scholar

- Gregory Vlastos, major Plato scholar

- Hans-Georg Gadamer, major Plato scholar

- Paul Woodruff, major Plato scholar

- Catherine Zuckert, Plato scholar and political philosopher

- Julia Annas, Plato scholar and moral philosopher

- John McDowell, translated Theaetetus in English

- Robin Waterfield, Plato scholar and translator in English

- Léon Robin, scholar of Ancient Greek philosophy, translator of the complete works of Plato in French

- Alain Badiou, French philosopher, loosely translated Republic in French

- Chen Chung-hwan, scholar and commentator, translated Parmenides in Chinese

- Liu Xiaofeng, scholar and commentator, translated Symposium in Chinese

- Michitaro Tanaka and Norio Fujisawa, translators of the complete works of Plato in Japanese

- Joseph Gerhard Liebes, major scholar and commentator, the first to translate Plato's complete works in Hebrew

- Margalit Finkelberg, scholar and commentator, translated Symposium in Hebrew

- Virgilio S. Almario, translated Republic to Filipino

- Mahatma Gandhi, translated Apology in Gujarati

- Zakir Husain, Indian politician and academic, translated Republic in Urdu[189]

- Pierre Hadot, scholar and author of commentaries of Plato in French

- Luc Brisson, translator and author of commentaries on several works of Plato, and editor of the complete French translations; widely considered to be the most important contemporary scholar of Plato[190]

Other

- Oxyrhynchus Papyri, including the Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 228, containing the oldest fragment of the Laches, and Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 24, that of the Book X of the Republic

- Plato, a lunar impact crater on the Moon aged 3.8 billion years, named after the Greek philosopher

Notes

- ^ "...the subject of philosophy, as it is often conceived—a rigorous and systematic examination of ethical, political, metaphysical, and epistemological issues, armed with a distinctive method—can be called his invention."[3]

- ^ "Though influenced primarily by Socrates, to the extent that Socrates is usually the main character in many of Plato's writings, he was also influenced by Heraclitus, Parmenides, and the Pythagoreans"[6]

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius mentions that Plato "was born, according to some writers, in Aegina in the house of Phidiades the son of Thales". Diogenes mentions as one of his sources the Universal History of Favorinus. According to Favorinus, Ariston, Plato's family, and his family were sent by Athens to settle as cleruchs (colonists retaining their Athenian citizenship), on the island of Aegina, from which they were expelled by the Spartans after Plato's birth there.[14] Nails points out, however, that there is no record of any Spartan expulsion of Athenians from Aegina between 431–411 BC.[15] On the other hand, at the Peace of Nicias, Aegina was silently left under Athens' control, and it was not until the summer of 411 that the Spartans overran the island.[16] Therefore, Nails concludes that "perhaps Ariston was a cleruch, perhaps he went to Aegina in 431, and perhaps Plato was born on Aegina, but none of this enables a precise dating of Ariston's death (or Plato's birth).[15] Aegina is regarded as Plato's place of birth by the Suda as well.[17]