Ideal (ethics)

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

(Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

An ideal is a principle or value that an entity actively pursues as a goal and holds above other, more petty concerns perceived as being less meaningful.[2] Terms relating to the general belief in ideals include ethical idealism,[3] moral idealism,[4] and principled idealism.[5] A person with a particular insistence on holding to ideals, often even at considerable cost as a consequence of holding such a belief, is usually called an ethical idealist, moral idealist, principled idealist, or simply an idealist for short. The latter term is not to be confused with metaphysical idealism, a viewpoint about existence and rationality unrelated to the ethical concept.[citation needed] The term ideal is applied not only to individuals but also to organizations large and small from independent churches to social activist groups to political parties to nation states and more. An entity's ideals usually function as a way to set firm guidelines for decision making, with the possibility of having to sacrifice and undergo loss being in the background. While ideals constitute fuzzy concepts without that clear-cut a definition, they remain an influential part not just of personal choice but of larger, civilization-wide social direction. Ideals as a topic receive both scholarly and layman discussion within a variety of fields including philosophy both historically and more recently.[citation needed]

In the broader context of ethics, the very terms ethical and ideal are inherently tied. Philosopher Rushworth Kidder has stated that "standard definitions of ethics have typically included such phrases as 'the science of the ideal human character'".[6] Whether based in religious traditions or fundamentally secular, an entity's relative prioritization of ideals often serves to indicate the extent of that entity's moral dedication. For example, someone who espouses the ideal of honesty yet expresses the willingness to lie to protect a friend demonstrates not only devotion to the different ideal of friendship but also belief in that other ideal to supersede honesty in importance. A particular case of this, frequently known as 'the inquiring murderer', is well known as an intellectual criticism of Kantianism and its categorical imperative.[citation needed] Broader philosophical schools with a strong emphasis on idealistic viewpoints include Christian ethics, Jewish ethics, and Platonist ethics.[7] The development of state-based and international ideals in terms of large-scale social policy has additionally been long studied by scholars, their analysis looking particularly at the psychological foresight and determination required to manage effective foreign policy. Democratic peace theory in international relations study is an example.[citation needed] Idealism in the context of foreign relations generally involves advocating for institutions that enact measures such as international law implementation in order to avoid warfare.[8]

A variety of different issues in analyzing idealistic ethics exist. Specifically, scholars such as Terry Eagleton have opined that the practical plausibility of particular ideals winds up being inverse to their intellectual legitimacy. Thus, an idealist with values at odds with his or her actual behavior stands apart, in Eagleton's view, from one who sets forth his or her ethics based fundamentally on his or her pragmatic desires, the latter person's set of principles losing the philosophically appealing nature of the former person's views.[9] As well, thinkers such as Richard Rorty have criticized the very concept of unchanging ideals existing somewhat separately from human nature in the first place.[7] In the political context, scholars such as Gerald Gaus have argued that particular strains of idealism cause individuals to wish for impossible political perfection and thus lose their sense of what constituents practical policy advocacy, ideals getting in the way of incremental yet meaningful progress.[10] Historically, advocates for idealism in the context of the "Age of Enlightenment" include Immanuel Kant and John Locke. Their emphasis on rational thinking led them to develop theories of ideal morality based around reason. Works authored by the former on the topic include the initial publication The Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals followed by The Critique of Practical Reason, The Metaphysics of Morals, Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View, and Religion within the Boundaries of Mere Reason, the later commentaries developing the intellectual figure's thinking.[11] To Kant, no clear-cut divide exists between morality and the natural world, with empirical analysis of human psychology dovetailing with ethical analysis.[12]

In terms of demonstrated life experience and the proliferation of personal stories via mass media, multiple idealistic individuals have received attention as moral examples for others to draw understanding from. For instance, United States leaders known for their idealism include presidents Theodore Roosevelt,[13][14] Ronald Reagan,[15][16] and Barack Obama,[17][18][19] while European officials similarly known for such ethical attitudes include Konrad Adenauer, Prime Minister of Germany,[20][8][21] Charles de Gaulle, Prime Minister of France and senior general,[16] and Vaclav Havel, dissident and President of Czechoslovakia.[22][23] Juan Manuel Santos of Colombia has gained attention in terms of the central and south Americas.[24][25] Private individuals known for their prominent ideals include Fred Rogers, U.S. television personality,[26] and Terry Fox, Canadian athlete and charity advocate.[27][28][29] Multiple idealistically optimistic characters have been featured in prominent creative media, the Star Trek franchise centered around space exploration being a well-known instance of fictional idealism.[30][31] In addition, musical artists known for creating songs with an atmosphere of idealism include singer-songwriters David Bowie,[32] Curtis Mayfield,[33] and Tom Paxton,[34] with bands The Beatles,[35] Queen,[36] and Maze being examples as well.[37]

Background and history[edit]

Applications of different terminology[edit]

The term "idealism" and the related labeling, whether self-applied or otherwise, of individuals and/or groups as being "idealistic" or against such viewpoints has a certain complexity to it. In the sense of metaphysical thought, "idealism" is generally described as centering around a particular view of objective reality versus the perception of reality; the question of whether or not potential knowledge exists independently to humanity or whether such knowledge is solely tied to experiences in the mind gets debated. Even within that particular intellectual sphere, the stamp of "idealist" as applied to particular philosophers, with them often possessing rather nuanced views, attracts considerable controversy.[citation needed]

In colloquial language, the term "ideal" is often applied loosely, with varying circumstances getting described as such in highly different contexts. For instance, in cooking the descriptions of certain ingredient portions, heating temperatures, preparation times, and the like are often labeled as "ideal" or otherwise. Such uses of the term are often distinct from the historical and social concept of having an "ethical ideal" as such.[citation needed]

Definitions and justifications[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

American scholar Nicholas Rescher has drawn upon ancient philosophy to state that the metaphysical nature of ideals gives them a particular status as "useful fictions" in terms of their special existence, writing in his book Ethical Idealism: An Inquiry Into the Nature and Function of Ideals,

"The 'reality' of an ideal lies not in its substantive realization in some separate domain but in its formative impetus upon human thought and action in this imperfect world. The object at issue with an ideal does not, and cannot, exist as such. What does, however, exist is the idea of such an object. Existing, as it must, in thought alone (in the manner appropriate to ideas), it exerts a powerful[ly] organizing and motivating force on our thinking, providing at once a standard of appraisal and [also] a stimulus to action."[3]

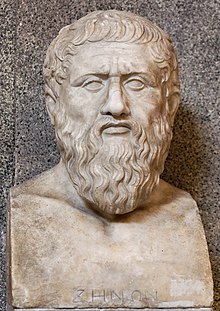

Nonetheless, multiple thinkers have asserted that ideals as such constitute things that ought to be said to exist in the real world, having a substance partly to the same extent as flesh and blood people and similar concrete entities. A prominent example of this certain viewpoint is the iconic Greek philosopher Plato. To him, ideals represent self-contained objects existing in their own domain that humanity discovered through reason rather than invented out of whole cloth for narrow benefit. Thus, while existing in relation to the human mind, ideals still possess a certain kind of metaphysical independence according to Plato.[3]

With respect to specific definitions, U.S. philosopher Ralph Barton Perry has defined idealistic morality as being the result of a particular viewpoint about knowledge itself, writing in his book The Moral Economy,

"Moral idealism means to interpret life consistently with ethical, scientific, and metaphysical truth. It endeavors to justify the maximum of hope, without compromising or confusing any enlightenment judgement of truth. In this it is, I think, not only consistent with the spirit of a liberal and rational age but also with the primary motive of religion. There can be no religion... without an open and candid mind as well as an indomitable purpose."[4]

Focusing on the practical nature of moral choices, recent scholarly analysis in journals such as Academia Revista Latinoamerica de Administracion have framed definitions in terms of social decision making, one study stating,

"Idealism concerns the welfare of others. On one hand, a low idealist assumes that harming others is not always avoidable and that sometimes harm may be necessary to produce good[.] [...] On the other hand, a high idealist assumes that harming others is always avoidable and that it is unethical to have to choose between the lesser of two evils. In other words, for a high idealist, morality always results from not harming others".[38]

Ethical idealism has often defined either in relative comparison to or in direct contradiction to the doctrine of moral relativism. The latter concept has been associated with a philosophical skepticism in which an individual questions the value of commonly held cultural principles. A strongly relativist person will, scholars have stated, judge morality according to particular circumstances. Individuals with stridently idealistic beliefs and little sense of relativism have been known as "absolutists" while those with principles seeking to synthesize those two concepts have been known as "situationists".[38]

Historical development and recent analysis[edit]

Ideals from antiquity to the Age of Reason[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

In the wider context of ethics, the very terms "ethical" and "ideal" have been inherently tied. Philosopher Rushworth Kidder has stated that "standard definitions of ethics have typically included such phrases as 'the science of the ideal human character'".[6] Thus, ideals have been the topic of discussion and debate since the beginnings of organized human civilization. The types of ideals dealt with during the history of philosophy have varied widely over the many centuries, many conceptions existing of what moral idealism actually is and how it gets applied in actual life experiences.[citation needed]

From the far distant history to today, multiple philosophers have remarked that human beings appear to, by instinct, behave in a matter with few if any ideals and even general morals of whatever kind. The works of British thinker David Hume, for instance, explicitly declared people to be inherent "slaves" to their passions.[11] When articulating a particularly nuanced theory of morality, Hume's writings labeled it folly to emphasize what people hopefully wish to achieve and additionally argued that enforcing ideals without proper grounding in practical, already existing mores undermines society itself.[40]

Cynics of the ancient world frequently referred to humanity in general as not only not perfectible but fundamentally depraved. The historical Greek figure of Diogenes, while arguing that some individuals could through great effort achieve some kind of a moral dignity, was a prominent example in his dismissal of the values common in his day. He sought his own path based on a particular set of ideals that involved begging on the streets, living in a barrel, and wearing rags.[39]

In both Jewish ethics and later Christian ethics, however, advocacy for a stridently idealistic view of the world, in which principles get held over personal convenience and even otherwise perfectly logical expectations, has attracted praise. Golden rule based moral standards have involved restrictions such as holding back the quest for vengeance by the wronged such that punishment only gets applied in a limited, specific fashion, this example being later evaluated as the tit-for-tat strategy in game theory. In terms of Christianity, the teachings of the Gospels have constituted an extension of the golden rule; individuals, under Jesus' example, have gotten called to hold to the ideal of treating other people even better than they rationally expect to be treated back.[citation needed]

In the context of the various religious movements of the 1st and 2nd century in the Roman Empire, the ideals of Christian thinking constituted a radical break with the ethical doctrines that had been advocated by those in power. Rejecting views of the upper classes, both during the empire's time and previously in Greco-Roman civilization, the rising Christian community set forth clear-cut principles based on narratives such as the Sermon on the Mount, which was included in the Gospel of Matthew. Specifically, Jesus' exhortations for his followers to "turn the other cheek" as well to "love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you" and practice other idealistic behaviors established a general view emphasizing spiritual standards over material concerns.[41]

Despite the degree that Christian viewpoints contradicted Roman traditions, early Christianity spread throughout the Empire and became a particularly robust force in the empire's society by the 4th century. Reasons for the appeal included not only the idealistic messages but also the similarity between the belief system and previously popular mystery cults. Finally, emperor Theodosius the Great made Christianity the official religion of the entire realm.[41]

While Western nations widely retained the influences of Jewish and Christian morality over multiple centuries, in practical terms a great many powerful rulers and prominent thinkers both before and after the fall of the Roman Empire pushed back on higher notions of idealistic ethics. Many did so based on little other than expediency. However, whether explicitly in words or implicitly through deeds, more cynical figures have counter-argued from points of view that can broadly be labeled as "moral relativism". As the arguments have gone, human beings have been little more than crude matter and cannot reasonably be held to act based in any sort of larger principle; survival has remained people's core instinct such that civilization, through relativist eyes, functions as a thin veneer over base instincts.[citation needed]

Multiple philosophers have argued in favor of particular types of idealism as well for years. The course of the "Age of Enlightenment" (also known as the "Age of Reason") from the 17th to the 19th centuries, being a movement that in large part centered around the application of rationality-based principles such as the scientific method upon human nature, caused increased interest in ethical philosophy as a field of study. Notions of "benevolence" attracted widespread attention in terms of governance, with leaders exhorted to act based on idealistic principles and to particularly champion causes such as the facilitating of the arts, increased educational efforts, effective stewardship of national resources, and so on. This movement increased trends away from absolute monarchy and dictatorship towards that of constitutional monarchy and republican government. The scientifically based, forward thinking viewpoint about human nature when applied to socio-political organization became later known as "classical liberalism".[citation needed]

In terms of broader discussions on ethics, many classical Enlightenment thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes and John Locke have famously argued that strong moral standards on individual choice exist based upon standards of rationality that can be found through logical analysis by reasonable observers. Specifically, instrumental principles based on satisfying one's desires made up the basis for morality through Hobbes' approach. External principles existing in the discoverable state of nature outside of human experience that became possible to tease out due to personal study constituted Locke's theoretical background for ideals and broader ethics.[11]

With respect to social order, Locke's highly influential writings applied rational principles to governance in support of the doctrine of social contract theory, which permeated Enlightenment discussions about the best form of organizing a country. Locke's works such as the Two Treatises of Government set forth an ethical framework in which rational individuals establish a government in order to guarantee their fundamental rights and possess the understanding that they not only can but should alter said government when rational application of the fair-minded "rule of law" has broken down. Thus, Locke labeled fundamental change as a natural consequence of when liberty no longer receives protection. He criticized competing theories such as the divine right of kings, which the thinker viewed as folly.[citation needed]

In terms of individual thinking on principles, Locke never wrote a single work laying down in depth his conceptual understanding of ethics and morality. However, Lockean thought as described in various writings have emphasized holding to prominent ideals about human behavior in terms of the rational capacity for good, a particular topic of Locke's concern having been the power of education. Locke wrote of its importance within the pages of Some Thoughts Concerning Education. Outlining the best way to rear children in his eyes, Lockean arguments stressed that virtuous actions by adults arose as a direct result of the habits of body and mind taught during youth by forward thinking instructors.[citation needed]

Locke wrote in his work An Essay Concerning Human Understanding dividing rational understanding into three inherent areas of scope, the philosopher defining the second as "practica" and describing it as,

"The skill of right applying our own powers and actions, for the attainment of things good and useful. The most considerable... is ethics, which is the seeking out those rules and measures of human actions, which lead to happiness, and the means to practise them. The end of this is not bare speculation and the knowledge of truth; but right, and a conduct suitable to it."[42]

German philosopher Immanuel Kant's particular view of human nature and intellectual inquiry, later summed up under the banner of "Kantianism", stressed the inherent power of logical thinking in terms of moral analysis. Kant's advocacy for the "categorical imperative", a doctrine through which every individual choice has to be made with the consideration of the decider that it ought to be a universally held maxim, took place in the broader context of his metaphysical views. In Kant's writings, defiance of higher idealistic principles was not only wrong in a practical sense but in a fundamentally rational and thus moral sense as well.[11]

Works authored by Kant on the topic include the initial publication The Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals followed by The Critique of Practical Reason, The Metaphysics of Morals, Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View, Religion within the Boundaries of Mere Reason, the latter commentaries developing the intellectual figure's thinking.[11] Within the pages of Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View in particular, the philosopher articulated a vision of people as by their very essence driven by meaningful ethics. Through the lens of Kant's doctrine, no ironclad divide has existed between morality and the natural world, with empirical analysis of human psychology dovetailing with studies of people's ideals.[12]

The philosopher's metaphysics tied closely with his socio-political views and belief in evolutionary advancement, Kant writing in The Critique of Pure Reason in detail,

"What the highest level might be at which humanity may have to come to rest, and how great a gulf may still be left between the idea [of perfection] and its realization, are questions which no one can, or ought to answer. For the matter depends upon freedom; and it is in the very nature of freedom to pass beyond any and every specified limit."[43]

Summing up Kant's views on ideals specifically in context, scholar Frederick P. Van De Pitte has written about the primacy of rationality to the philosopher, Pitte remarking,

"Kant realized that man's rational capacity alone is not sufficient to constitute his dignity and elevate him above the brutes. If reason only enables him to do for himself what instinct does for the animal, then it would indicate for man no higher aim or destiny than that of the brute but only a different way of attaining the same end. However, reason is man's most essential attribute because it is the means by which a truly distinctive dimension is made possible for him. Reason, that is, reflective awareness, makes it possible to distinguish between good and bad, and thus morality can be made the ruling purpose of life. Because man can consider an array of possibilities, and which among them is the most desirable, he can strive to make himself and his world into a realization of his ideals."[43]

Ideals in post-Enlightenment thought[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

Broadly speaking, Western philosophy in terms of its discussion of ideals largely takes place within the framework of Enlightenment thinking, with figures such as the aforementioned Hobbes, Kant, and Locke dominating debate. In the shadow of material such as the United Nation's Universal Declaration of Human Rights, itself an evolution from the earlier American Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States as well as similar such documents in the history of human rights, many theorizing academics of the 19th century and the 20th century have set forth an optimistic view in which even radically different cultures possess shared ethical values common to humanity in general that both nations and individuals can aspire towards. This idealism has found particular emphasis in discussions of socio-political issues.[citation needed]

Through this moralistic lens, all people by nature of their mere existence have been thought to have been born inherently good, inherently equal, and inherently free. This doctrine has been seen to hold all bigotry, discrimination, and prejudice as inherently wrong not only ethically but logically as well. Although varying greatly in application based on the social context, the framework of the age of reason has overall continued to represent the intellectual stream that has fed the waters of more recent discussions.[citation needed]

A defining inflection point of this trend has been the experience of World War II and the Holocaust. The historical memory has been argued to have created a sort of dualistic approach to ideology in which capitalistic democracy, centered around classical liberalism, gets inherently pitted forever in struggle with tyrannies, centered around the stratification of various groups over others and mass misery. In the aftermath of the end of the Cold War, studies upon moral idealism have often asked if Enlightenment viewpoints face an inherent intellectual challenge that the doctrines cannot eventually overcome.[citation needed]

Examples of specific post-Enlightenment philosophers who have garnered notice for their defense of the movement's ideals include Ernst Cassirer. The thinker's advocacy for liberal democracy at a time when the rise of fascism and other doctrines faced an environment that found his views unfashionable. A German Jew who had staunchly supported the Weimar Republic in power before the Nazi Party's takeover and fled for his family's own safety, Cassirer wrote philosophical investigations of art, language, myth, and science.[44] In terms of human progress, Cassierer remarked that "what is truly permanent in human nature is not any condition in which it once existed and from which it has fallen; rather it is the goal for which and toward which it moves."[43] This theories merged the study of human cultures and particularly their symbols with higher philosophy, Cassierer strongly defending the path of history as that of "man's progressive self-liberation."[44]

With the advent of the 21st century, philosophizers have debated the rapid evolution of different societies, particularly given advancing technology, and the seeming acceptance of egalitarian values previously thought of as radical or undesirable by center-left, moderate, and center-right individuals. The conflict between these people, many of them belonging to younger generations such as the Millennials, and those political extremists of the global far-right movement, the social trend often called "new nationalism", has defined new distinctions between what it means to be a "moral idealist". As well, the question of the fundamental biological advancement of humanity itself has attracted much attention. What a transhuman or even posthuman individual would possess terms of ideals in contrast with regular human beings has remained an open question.[citation needed]

In the broadest sense, the question of whether or not humanity as a whole has fundamentally progressed towards a set of moral ideals over the past multiple centuries has never achieved any particular consensus. Examples of philosophers who argue partially in support of the notion include the American thinker Richard Rorty, a figure who has criticized the very concept of unchanging ethical principles set forth in inherent nature while still lauding general social progress.[7]

In contrast, multiple scholars concerned with issues such as global climate change and potential use of weapons of mass destruction in future warfare have lamented particular technological advancements and related alterations in broader social culture, the thinkers arguing that fundamental moral progress has truly not occurred given forms of increasing danger to humanity. The evolution of particular scientific areas such as artificial intelligence research has generated concerns about long-term threats and the possibility of eventual human extinction. Critical views have also been set forth by various religious philosophers who have argued that humanity remains full of sin in its general behavior, this trend perhaps even getting worse as time has passed. Multiple secular thinkers have made similar comments about the proliferation of moral breakdown, particularly in the context of the rise of post-factual politics and the related issue of politicization.[citation needed]

A contrasting approach arising in the 20th century and continuing to receive notice is that of prominent Roman Catholic figure Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. He famously predicted that humanity will eventually advance in terms of not just scientific development through natural and engineered biological evolution but also idealistic morality to a sort of final oneness regarded by him as the 'Omega Point', a mode of existence taking place not only without hatred, pain, and misery but with perfect collective action and consciousness. Known as the "Catholic Darwin", his view of evolutionary advancement came out of a religious context through which he identified humanity's final state with Jesus Christ as the "Logos" or sacred "Word". To Chardin, the power of love has constituted a sort of elemental drive as strong as that of fire and other natural forces.[45][46][47] A geologist, paleontologist, and Jesuit priest, Chardin was later described by a Cyclopedia of World Authors volume as having "combined his scientific beliefs and Christian convictions in an idealistic [and] evolutionary vision of the universe."[47]

Pope Benedict XVI notably made an approving reference to Chardin's views within a reflection on the Epistle to the Romans during a vespers service in Aosta Cathedral, the Pope asserting before the audience,

"It's the great vision that later Teilhard de Chardin... had: At the end we will have a true cosmic liturgy, where the cosmos becomes a living host. Let's pray to the Lord that he help us be priests in this sense, to help in the transformation of the world in adoration of God, beginning with ourselves."[45]

Debates and discussions involving ethical theory[edit]

In applied ethics[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

The specific philosophical school known as "applied ethics" has frequently involved discussion over ideals and the desirability of holding to them or abandoning them, depending on the context. In some theories of applied ethics, relative importance has gotten assigned to certain social preferences over others as a way to resolve disputes effectively. In analysis of legal theory, for instance, judges have been sometimes called on to resolve the balance between the ideal of truth, which would likely advise hearing out all evidence, and the ideal of broader social equality, which would likely advise seeking to restore goodwill between individuals regardless of specific findings during a particular case. Said judges have also been required to consider the principle of the right to a speedy trial as well, which places limits on the previous two ideals given the time involved in ferreting out details.[citation needed]

In an August 2005 address, philosopher Richard Rorty remarked upon the "moral idealism common to Platonism, Judaism, and Christianity" and the related notion of strictly specified principles through the lens of applied ethics, asserting to a group of business professionals,

"[I]ndividuals become aware of more alternatives, and therefore wiser, as they grow older. The human race as a whole has become wiser as history has moved along. The source of these new alternatives is the human imagination. It is the ability to come up with new ideas, rather than the ability to get in touch with unchanging essences, that is the engine of moral progress."[7]

In medical ethics[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

Academic specialists such as physician and scholar Matjaž Zwitter have raised concerns that inadequate preparation in medical school, with instructors failing to teach challenges including having to work inside substandard facilities and facing difficult time restrictions, set young professionals up to have their idealism drained quickly when they begin real practice. This, the argument has gone, causes major issues in terms of medical ethics. Individual physicians possibly have faced unfair burdens due to general issues with national healthcare systems getting placed onto their shoulders, with this making their idealistic views falter even more.[48]

Fading idealism has been cited as a contributor to the serious issue of burnout among medical professionals.[48]

In secular ethics[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

With the widespread movement away from traditional religious beliefs in both the Anglosphere and other nations during the 20th century and into the 21st century, the question of to what extent the ideals held by the irreligious owe a debt to particular faith groups has attracted much attention. Specifically, certain authors known as "new atheists" such as biologist Richard Dawkins and journalist Christopher Hitchens have argued that newly emerging forms of secular ethics constitute an approach of people treating each other that is more logical, just, and reasonable when seen as a rejoinder to previous forms of "traditional values". At the same time, multiple thinkers have advocated for moral relativism and a reduced or non-existent sense of holding to previously well-promoted ideals as a direct result of their wholesale rejection of religion. As well, scholars regardless of personal faith background have commented about the complex nature of ethics when taken from spiritual movements.[citation needed]

Idealistic appeals in practice[edit]

In conceptual and historical politics[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

Ideals have played a role in politics for millennia. For example, iconic Greek statesman Pericles famously presented an ideal-based view of the Mediterranean world. In 431, shortly after the Peloponnesian War had started, Pericles' "Funeral Oration" made to commemorate fallen soldiers, described for posterity by the historian Thucydides, presented a view of Athens and the city-state's broader civilization that emphasized a sense of cleverness and open-mindedness that Pericles believed gave it the strength to rise to different challenges.[49] Other early historical figures known for appealing to ethical ideals in their oratory include Roman statesman Cato the Elder, the figure's commentary on Hellenized values leading to his moral appeal among supporters. In contrast to what he saw as decadence spreading into Rome and nearby areas from elsewhere, Cato articulated support for what he labeled as traditional Roman ethics.[citation needed]

Most political revolutions have drawn support from the mass appeal of a certain moral idealism in contrast to the doctrines of those holding power, having the various grievances with the status quo created from real or perceived misrule spark ethical debate. During the French Revolution, the rhetorical principles of "Liberté, égalité, fraternité" (English: "Liberty, Equality, Brotherhood") got raised to the status of clear-cut ideals; the new nation state constituted a sort of grand experiment in what became in de facto and later de jure a new religion. Many political movements in modern times have centered themselves upon multiple ideals found to be mutually reinforcing. Recent examples have included the peace movement and the broader opposition expressed worldwide to war in Afghanistan and Iraq as well as elsewhere.[citation needed]

In many cases current and historical, instances have popped up in which proclaimed ideals simply weren't lived up to by various figures while in office, despite claims made by the officials before taking power and since attaining it. In British English, politicians openly changing their opinions in defiance of previous assertions about their ethics have been labeled as making a "u-turn". In American English, similar individuals have been pejoratively called "flip-floppers". While different, the terms have meant the same thing.[citation needed]

Idealism in the context of politics has attracted criticism from multiple fronts. For instance, U.S. philosopher Gerald Gaus, the author of The Tyranny of the Ideal: Justice in a Diverse Society, has prominently argued that an overriding emphasis on ideals causes individuals to wish for impossible political perfection and thus lose their sense of what constituents practical policy advocacy as well as logical choices during elections. Gaus has made other warnings such as cautioning that people can lose their sense of how much has already been achieved and how well current situations have become in certain circumstances. In general, Gaus has advocated for compromise and incremental socio-political reform.[10]

In traditional achievement[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

In a less abstract sense, multiple famous private individuals have been thought to embody certain ideals due to multiple factors such as their courage, intelligence, personal endurance, and so on. Although existing in real life and thus being subject to complexities that philosophical thought experiments often don't feature, these moral examples have established a link between dry intellectual principles and broader issues found in regular people's decision making. Naturally, even the famous have possessed diverse and multi-faceted traits. To get considered representative of an ideal has usually constituted a necessary simplification process; with only a few traits on prominent display, some individuals have become easy archetypes which others have tried to mimic.[citation needed]

For instance, disabled athlete Terry Fox has been a prominent example of idealistic values. Known for his "Marathon of Hope", Fox's public running helped raise huge amounts for charity and spread awareness of the achievement possible among those possessing a handicap (in Fox's case, a lost leg due to cancer).[27][28][29] An article from Maclean's has referred to him simply as: "The humanitarian, the athlete, the idealist."[29] Within Fox's native Canada, his actions have earned him praise many years after his life ended, attracting commentary labeling him a "hero".[28]

Fox finished second to politician Tommy Douglas in the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation program The Greatest Canadian, which the organization broadcast in 2004.[50] Fox's iconic status has been attributed to his image as an ordinary person attempting a remarkable and inspirational feat.[28][29] Aside from Fox's organization engaging in decade-spanning work successfully raising funds for Canadian health, his foundation achieving a total of over $750 million in donations as of 2018,[27] Fox's legacy additionally includes the promotion of social tolerance and active inclusion between the broader society and those with disabilities.[28][29] The athlete had optimistically aimed to motivate his nation enough to raise a dollar from every single Canadian, and his organization managed to greatly exceed that after his death.[27]

Commenting in depth on Fox's set of ideals, Maclean's journalists Dan Robson and Catherine McIntyre have remarked,

"During those early days of his 'Marathon of Hope', as he covered the equivalent of a marathon a day, very few people knew of the 21-year-old from Port Coquitlam, B.C. But through the spring and summer of 1980, Fox captivated the nation with his display of will and strength. And nearly four decades later, his legacy continues to inspire people around the world. In what would be the final stretch of his journey, Fox's daily progress through the northern Ontario landscape was a moving picture of humility, dedication and unrelenting courage... [blazing] a trail that inspired millions to follow."[29]

As well, multiple figures with a sincerely revered or otherwise prominent status within religious and broadly spiritual beliefs have been seen by individuals within those movements as representative of an ethical idealism worth mimicking. In Islam, for instance, the life of the prophet Muhammad has been held up as a comprehensive ideal for Muslims to study. However, all of his words and deeds must be interpreted for believers through the lens of his life's broader path and the larger religious context, according to Islamic scholars. Multiple other prophets exist in Islam and have been considered worth devoted study including Jesus and previous figures such as Abraham and Moses.[citation needed]

In the Jewish context, the term "mensch" has gotten frequently used to describe an individual of great worth due to his or her moral actions. Originally coming from Yiddish, the labeling of idealistic people as such has since become co-opted into regular use within the English language in certain areas.[citation needed] Different scholarly traditions within Judaism have articulated theories of promoting moral behavior as well as more generally seeking to improve both humanity and nature in order to meet higher ideals; the process has been known as "tikkun olam", a term often translated to mean "repairing the world". In 2013, the surveying analysis group Pew Research Center polled American Jews what specific traits were essential to Jewish identity and found that 56% said "working for justice/equality".[51]

Christian thinking has often encouraged regular people to highlight certain individuals as ethical examples. In both Eastern Orthodoxy and the traditions of the Roman Catholic Church, saints have received veneration due to their heroic deeds. Within Protestantism and other sects, similar practices have taken place in terms of holding up particular believers for widespread adulation.[citation needed]

Another famous example of a self-described "starry-eyed idealist" getting notice has been the reverend and television personality Fred Rogers. Known for hosting the iconic program Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, Rogers later stated that he started out "bursting with enthusiasm for the potential I felt that television held not only for entertaining but for helping people."[26] His widely praised work in children's television for the American station PBS over multiple decades involved tackling various issues unusual for a program of his nature, including discussing with children the nature of divorce and helping them comprehend death. Variety has frankly remarked that Rodgers "attempted to change the world."[52]

The host's personal image became a major part of his programming, with Rogers wearing a prominent hand-knitted cardigan and using a voice that maintained both a soft yet deliberate tone. This clothing additionally featured colors such as pink and lavender that have stereotypically perceived as un-masculine. Although slender as an adult, Rogers mentioned being overweight as a child and experiencing bullying that led him to reject expressions of prejudice throughout his later life.[52] "There’s just one person in the whole world like you," he stated at the end of every episode, “and people can like you just the way you are."[26]

Upon Rogers' death from cancer in 2003, the U.S. House of Representatives voted unanimously to honor "his dedication to spreading kindness through example."[52] His idealistic approach to television hosting and broader advocacy for social progress in the U.S. brought Rogers a variety of honorary degrees and esteemed awards during his lifetime. The latter includes a Lifetime Achievement Emmy in 1997 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2002. Rogers' commentary, particularly regarding that of how to best respond to disasters and other moments of national crisis, has continued to attract attention into the 21st century years after his death.[citation needed] His life and legacy was detailed in the documentary film Won't You Be My Neighbor?, which came out in 2018.[52]

In united policy and international relations[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

With respect to government policy, appeals to idealistic values and the sense of reaching beyond petty concerns have long been a part of U.S. space exploration. For instance, the U.S. President's Science Advisory Committee published an "explanatory statement" in 1958 on the possible future of traveling through outer space using language later described by the Financial Times as "a shot of pure idealism." The white paper cited multiple reasons to enact a national space program. Yet it described as a core principle "the compelling urge of man to explore and to discover, the thrust of curiosity that leads men to try to go where no one has gone before".[30]

In terms of the idealism behind space-based research and development, astronaut and U.S. politician John Glenn, known for his orbits of the Earth in 1962 inside the capsule Friendship 7, wrote in 1987,

"As we approach the 21st century, I want to think we are outgrowing our need to exploit the resources of our planet earth– or reaches of space- for power or profit. I'd like to think that our explorations are more and more being directed toward increasing our knowledge and mastery of the physical universe. I see in the explorers of today men and women led by visions of wonders and unexpected discoveries, driven by curiosity and a quest for knowledge, and sustained by personal courage, faith[,] and strength."[53]

In general leadership terms, specific national officials known for their sense of personal idealism include American presidents Theodore Roosevelt,[13][14] Ronald Reagan,[15][16] and Barack Obama.[17][18][19] As well, European leaders such as Charles de Gaulle, French Prime Minister and senior general,[16] and Konrad Adenauer, German Prime Minister, have attracted notice for their steadfast ideals.[20][8][21] Outside of these Western nations, examples include Juan Manuel Santos of Colombia.[24][25]

Within American history, Theodore Roosevelt has been described by historian Doris Kearns Goodwin as a champion of the common person and a determined advocate for social progress, with a biography on him and his times being aimed by Goodwin to "guide readers" to "bring... [the] country closer to its ancient ideals". Having possessed an assertive personality with a striking physical image, Roosevelt has also garnered attention as an icon of American masculinity. Writers Robert Kagan and William Kristol have labeled the statesman an "idealist of a different sort" such that, unlike other leaders, Roosevelt "did not attempt to wish away the realities of power... but insisted that the defenders of civilization must exercise their power against civilization's opponents."[13]

Roosevelt himself notably cited his belief in idealistic morality when giving his speech upon receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1906, the statesman remarking,

"Moreover, and above all, let us remember that words count only when they give expression to deeds, or are to be translated into them... [M]any a tyrant has called it peace when he has scourged honest protest into silence. Our words must be judged by our deeds; and in striving for a lofty ideal we must use practical methods; and if we cannot attain all at one leap, we must advance towards it step by step, reasonably content so long as we do actually make some progress in the right direction."[14]

Fellow 20th century American leader Ronald Reagan's tenure as president of the U.S. began amidst a general atmosphere of malaise and uncertainty throughout the country's society. Yet the leader's deeply optimistic style managed to spread due to his advocacy for certain ideals.[16] In 2005, journalist Jamie Wilson of The Guardian stated that Reagan's "two terms as president heralded an era of unprecedented economic growth and restored pride to a nation still reeling from the" conflict in Vietnam.[54] Historian John P. Diggins has written that, in contrast to other approaches set forth during the Cold War for policy experts, the moralistic "Reagan was an idealist who put more trust in words than in weapons."[15] The Discovery Channel, surveying more than two million individuals in partnership with AOL, found Reagan to be the nation's greatest American in 2005.[54]

In terms of 21st century America, The New York Times commented in a 2018 article about Barack Obama that the then ex-president possessed a "signature idealism".[17] In terms of detailed analysis, professor Steven Sarson wrote in 2018 that the statesman acts and speaks like "a half-way utopian" that avoids "imposing prescriptive ideas" and thus admires those of absolutist views and personal zealotry in the cause of social advancement even while emphasizing with those individuals. Thus, Sarson argued that Obama remained "idealistic" but "free of blinding visions" given Obama's sense of practical compromise and willingness to tolerate diverse opinions, expressing an "ecumenical" approach.[18]

During his seminal speech titled A More Perfect Union, delivered in 2008 at the National Constitution Center, then presidential candidate Obama took stock of his particular view of the American experience and his own ethical idealism, commenting,

"[O]ur Constitution... had at is very core the ideal of equal citizenship under the law; a Constitution that promised its people liberty, and justice, and a union... [it] could be and should be perfected over time. And yet words on a parchment would not be enough to deliver slaves from bondage, or provide men and women of every color and creed their full rights and obligations as citizens of the United States. What would be needed were Americans in successive generations who were willing to do their part - through protests and struggle, on the streets and in the courts, through a civil war and civil disobedience and always at great risk- to narrow that gap between the promise of our ideals and the reality of their time."[19]

With respect to European history, Konrad Adenauer has been regarded in academic analysis as one of the "Founding Fathers of Post-War Europe",[8] with the statesman's sense of idealistic leadership reinvigorating West Germany after the chaos of World War II.[21] Historian Golo Mann, using terminology borrowed from the philosopher Plato, has labeled Adenauer a "cunning idealist" due to the statesman's experiences providing a profound sense of human frailty coupled as well with a gift for persuasion and a broad sense of always striving for the right.[20]

Being in the public eye during that same general era, Charles de Gaulle's lifelong pursuit of "a certain idea of France" and sense of socio-political ethics about the limits of power has also attracted notice. Writing for the Houston Chronicle, columnist Robert Zaretsky has labeled de Gaulle "an idealist who understood the need for pragmatism."[16] Known for his leadership in the French opposition to the Axis powers during the Second World War and his establishment of the new republican government that emerged after the conflict, thus gaining the reputation of having saved France, Kirkus Reviews has stated that the "uncompromising" and "incomparable character... acted as his country's conscience and rudder."[55]

Within the central and south Americas, Juan Manuel Santos of Colombia has received international acclaim for his idealistic efforts to end his country's long-running civil war.[24][25] After giving him the Nobel Peace Prize in 2016, the Nobel committee's official press release praised Santos' efforts, stating that the leader "has consistently sought to move the peace process forward".[24] In a 2018 column, Santos wrote that "the negotiation process and our efforts toward building a lasting peace constitute a true laboratory of ideas, experimentation, and lessons learned that could help find solutions in other parts of the world with similar or worse problems." In response to the label of being "an idealist", he remarked that he has "found that... it is always more popular to wage war than to seek peace" generally and more specifically "always more popular and more emotionally satisfying to pander to the extremes than to promote thoughtful, pragmatic centrist positions."[25]

In the broad sense, "idealism" in the sense of foreign policy can be defined as a viewpoint in which human rights and a generally positive view of the nation state gets encouraged, with warfare seen not as inevitable but as the result of avoiding constructive policies that would otherwise prevent conflict. Said policies often include the promotion of international trade as well as international law. Influenced by the thinking of Kant, the approach to international relations envisions a strong sense of morality as creating a more just world.[8] Specific foreign policy scholars identified with the school of idealism include S. H. Bailey, Philip Noel-Baker, David Mitrany, and Alfred Zimmern in the U.K. as well as Parker T. Moon, Pitman Potter, and James T. Shotwell in the U.S.[56]

Idealistic principles and their complexities[edit]

Creation of ideals in the psyche[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

Swiss psychologist Carl Jung proposed, based on his analysis of his patients' reporting of their struggles, a theory in which all individuals possesses within themselves a kind of mental structure based on three layers: the "personal conscious", the "personal subconscious", and the "collective subconscious". The former represents higher thinking and rationality while the latter two exist in a more shadowy realm that profoundly influences peoples' minds, Jung wrote, even as said individuals cannot reason through what happens subconsciously. The "collective" part of the subconscious, Jung determined, "constitutes a common psychic substrate of a suprapersonal nature which is present in every one of us" and comes about through existence itself.[57]

Thus, Jung stated that personal ideals arise out of abstract concepts held collectively in the subconscious to later see specific expression in the conscious based on particular contexts. He theorized that individuals think in terms of certain character forms that he labeled as "archetypes" and associated prominent traits to those forms; for instance, the archetypes of the "great mother" and "wise old man" embody the ideal of wisdom. As a result of all this, idealistic notions become seen in real-world people. The reverence of African leader Shaka Zulu on the continent has been cited as an example.[57]

Demographic differences[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

Despite the fact that behavioral philosophies develop at a personal level and get lived out as such, a variety of publications by multiple scholars have found that the broader social context matters. The cultural, historical, political, and religious background that individuals experience greatly influences their sense of ethical idealism, research has stated, such that aggregate views vary between specific groups.[38] Examples of studied categorizations include age, economic class, ethnicity, gender identity, nationality, and race. The general field of anthropology has explored the evolution of differing societies and come to contradictory conclusions about whether or not certain ideals can be said to be innate to human existence and/or universal in terms of rational advocacy.[citation needed]

Empirical research has demonstrated differences between men and women in terms of their relative approaches to moral idealism. Specifically, a 2012 report in the journal Academia Revista Latinoamerica de Administracion stated that four scholarly studies published in the past had determined that women appeared to be more idealistic than men while one had failed to detect any significant differences between the sexes. Finding similar results in its own analysis, the report speculated as a driving cause the notion that women express more concern over interpersonal relationships in comparison to men.[38]

The aforementioned article additionally evaluated distinctions in nationality and determined that significant differences exist between the various peoples when it comes to idealism. In depth, the analysis of Brazil, Chile, China, Estonia, and the U.S. seemed to the researchers to have illustrated the effects of contrasting social mores. Particularly strong notions of idealism appeared "consistent with the moral philosophies in the traditional Catholic and Islamic cultures" found in "Mediterranean ethics" as well as "Middle Eastern regions", the authors of the study stated, while nations with a considerably pragmatic and utilitarian social undercurrent possess less idealistic people. The U.S. was cited as a prominent example of the latter type of country.[38]

As well, a 2008 report published in the Journal of Business Ethics concluded that "levels of idealism... vary across regions of the world in predictable ways" such that a nation's ethical "position predicted that country's location on previously documented cultural dimensions, such as individualism and avoidance of uncertainty".[58]

Studies have additionally evaluated differences based on varying generations in terms of their ideals. The aforementioned Academia Revista Latinoamerica de Administracion report concluded that particular gaps exist between age groups. Broadly speaking, the older an individual was, the more importance they gave to idealistic ethics according to the analysis.[38]

Research has also found a positive relationship with beliefs in idealism and religiosity.[38]

Ideals versus absolute or conditional obligations[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

Philosopher Norbert Paulo has stated that, in common life, ideals as such appear to exist in relation to general social obligations. Many of the latter concepts have tended to appear, according to Paulo, absolute and essentially mandatory while also existing in highly particular circumstances. For instance, Paulo has written, physicians and nurses face a variety of ethical obligations imposed on them when treating their patients that regular individuals encountering said patients randomly do not. He had added that a continuum exists between clear-cut, widely held obligations applied via social norms and vague ones only partially behold to cultural sanction.[2]

Paulo's argument, thus, has concluded that idealist behavior takes place at a behavioral and mental level above and beyond mere social rules, such actions being "warranted" yet "not strictly required" either while their optional nature sets them up as being "praiseworthy". Ideals represent a method of putting into action an individual's personal character and its given traits such that, Paulo has argued, moral standards get fleshed out beyond the rigid framework of mere obligations. One person's altruistic caring for another generally has constituted a particular example.[2]

Ideals versus virtues[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

The line between an ideal and a virtue has been difficult to access. Ideals have been argued to inherently involve aspirations while virtues function as direct guides for assigned conduct given social standards.[2] Analysis has run into problems given that both entities are fuzzy concepts. In general, some philosophers have argued that an ideal usually constitutes something more inherent that one can make a habit while virtues, instead, necessarily involve going above and beyond regular decision making in order to actively strive for something. Thus, these thinkers have stated, virtues inherently constitute a behavior that's by its very nature highly difficult to turn into a regular practice. Other philosophers have made the exact opposite argument and seen virtues as fundamentally philosophically weaker entities than ideals.[citation needed]

Given the complexity of putting ideals into practice, not to mention resolving conflicts between them, many individuals have chosen to narrowly pick a certain group of them and then harden them into absolute dogma. Political theorist Bernard Crick has stated that a way to solve this dilemma is to have ideals that themselves are descriptive of a generalized process rather than a specific outcome, particularly when the latter is hard to achieve.[citation needed]

Kant wrote in his work Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View pitting idealism against the enactment of personal vice, the philosopher arguing,

"Young man! Deny yourself satisfaction (of amusement, of debauchery, of love, etc.), not with the Stoical intention of complete abstinence, but with the refined Epicurean intention of having in view an ever-growing pleasure. This stinginess with the cash of your vital urge makes you definitely richer through the postponement of pleasure, even if you should, for the most part, renounce the indulgence of it until the end of your life. The awareness of having pleasure under your control is, like everything idealistic, more fruitful and more abundant than everything that satisfies the sense through indulgence because it is thereby simultaneously consumed and consequently lost from the aggregate of totality."[43]

Relative ideals[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

Robert S. Hartman has contended that since, colloquially, labeling an entity as ideal means that something is the best member of the set of all things of that class, thus the term has particular implications when used in an ethical context. For example, he has stated, the ideal student constitutes the best member of the set of all students in exactly the same way that the ideal circle is the best circle that can be imagined of the class of all circles. Since one can define the properties that the ideal member of a class should have, according to Hartman, the value of any actual object can be empirically determined by comparing it to the ideal. The closer an object's actual properties match up to the properties of the ideal, the better the object is to Hartman. Thus, a bumpy circle drawn in the sand is worse than a very smooth one drawn with a compass' aid, but both are better than a regularly made square.[citation needed]

For Hartman, the world in general has presented a situation in which each particular entity ought usually to become more like its ideal if possible. This entails that, in ethics, each individual should analogously to become more like the hypothetical ideal person, and a person's morality can actually be measured by examining how close they live up to their ideal self, in Hartman's view.[citation needed]

Totalizing ideals versus emergent ideals[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

The question of to what extent one can hold to certain ideals practically and how facing resistance will shape them has attracted debate from multiple thinkers. The related issue of to what extent idealistic morality held by individuals reflects broader cultures has done so as well. The extent to which human beings think through their behavior irrationally or rationally has been a major issue in these such discussions.[59][9]

One 21st century philosopher who has delved into the topics is Terry Eagleton. Writing in his book After Theory, he has commented critically about the practicality of ethical idealism, Eagleton arguing,

"Moral values which state what you ought to do are impressively idealistic, but too blatantly at odds with your behaviour. Moral values which reflect what you actually do are far more plausible, but only at the cost of no longer serving to legitimate your activity."[9]

Another 21st century philosopher who has questioned traditional understandings of idealistic morality is Kwame Anthony Appiah. In particular, his book As If: Idealization and Ideals examined the usefulness of the concepts and the processes through which they've been articulated. Appiah found fault in the general assumptions made by certain thinkers of human rationality and advocated for a larger understanding of the practical nature of the idealization process among scholars of multiple disciplines as well as laypeople.[59]

In depth, Appiah's book presented a nuanced picture of ethical idealism in the context of cultural organization, the philosopher writing,

"The history of our collective moral learning doesn't start with the growing acceptance of a picture of an ideal society. It starts with the rejection of some current practice or structure, which we come to see as wrong. You learn to be in favor of equality by noticing what is wrong with the unequal treatment of blacks, or women, or working-class or lower-caste people."[59]

Instances of morally idealistic views in created media[edit]

Idealism in film and television[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

Multiple forms of media in terms of filmed and serially televised production have portrayed issues surrounding ideals and characters facing tests of their personal ethics. The fictional universe of the Star Trek franchise has traditionally aimed to portray humanity in general through the lens of idealistic morality.[30][31] Creator Gene Roddenberry, a former pilot with the U.S. Air Force as well as an officer of the Los Angeles Police Department, prominently laced his character designs and overall plot threads with strong ideals such as toleration, religious skepticism, and the promotion of peace among different groups.[30] However, this has changed with the new tone of more recent productions,[30][31] a particular example being the series Star Trek: Picard.[31]

Centered upon the U.S. politics from a detailed perspective, the television program The West Wing notably portrayed a fictional administration that filtered the nation's issues through the lens of character of Jed Bartlet, the president being an idealist with a strong ethical drive and oratorical skills. Running from 1999 to 2006, the series had achieved influence not only in terms of fandom but in its legacy of inspiring multiple individuals' belief's about American democracy itself.The news website Vox.com has labeled it "a beloved show" and argued that "Washington can't escape The West Wing".[60]

With respect to movies and the golden age of Hollywood, the works of American filmmaker Frank Capra have long attracted attention for their ideals and overall presentation of regular life, particularly when it came to lead characters. Upon Capra's death, The New York Times published an article stating that his works "were idealistic, sentimental and patriotic", Capra's releases having "embodied his flair for improvisation and spontaneity" as well as his "buoyant humor".[61] The titular protagonist of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and his "backwoods ideals", as Variety put things, in the face of the U.S. federal government's corruption has been an example.[62]

Movies prominently featuring pre-teen acting have sometimes become known for their idealistic portrayal of childhood. The early filmography of silent picture star Jackie Coogan serve as an example. In that era, child performers became known for their exaggerated dramatics and for facing plots placing them in unfortunate situations in order to foster emotional resonance with audiences.[63]

To Kill a Mockingbird, released in 1962, has become known as one of the most idealistic movies in Anglo-American history. Leading character Atticus Finch, a crusading lawyer defending a man falsely accused of rape in a racially-charged atmosphere, was played by Gregory Peck. Upon the actor's death in 2003, journal The Guardian published a review of his life that labeled him the "screen epitome of idealistic individualism"; the actor's liberal values became as much a part of his public persona as his film career, Peck particularly taking a stand in his choice of roles against antisemitism. That same year, members of the American Film Institute voted Peck's character as Finch the greatest ever hero in motion pictures.[64][65]

An article published by the Michigan Law Review has remarked upon Finch's particular influence in terms of promoting idealistic views of American legal system among many lawyers as well as the character's broader legacy,

"As the legal profession becomes further unmoored from its noble ideals, Atticus serves as an important symbol for a profession struggling to live up to its potential. And while symbols are not the solution to a corrupt legal culture, it is important to have beacons to remind us that, at our best, lawyers are vehicles through which equal justice is realized. Atticus serves as such an example. He has inspired countless young men and women to embark on legal careers, and he continues to influence legal practitioners for the better."[65]

The original Star Wars trilogy made up of the movies A New Hope, The Empire Strikes Back, and Return of the Jedi have attracted commentary due to the character arc of series protagonist Luke Skywalker, a former farmer coming from a place of naivety and vulnerability to become a victorious hero. The films' creation intentionally drew upon Jungian archetypes of human psychology such that Skywalker's idealistic nature has gained an emotional resonance with audiences. The theory of the monomyth was important in the trilogy's coming into being as well.[66]

In terms of more recent films, the movie Wonder Woman and its titular protagonist has been cited as a commercially successful instance of idealism on the silver screen. Within the film's plot, the central character has to work against the machinations of the Greek god of war, Ares, as a matter of moral duty; learning of the First World War and the suffering of humanity, she has to act. Despite her innocence and lack of understanding about the world, the film has overall been cited as demonstrating the ability for an individual to make a difference out of love.[67][68] A reviewer for Radio Times labeled the protagonist "a heroine who lives up to the majesty of her moniker and stands apart from her superhero brethren, not just in her gender but in her well-communicated ideals."[68]

Anime has frequently featured characters acting out of broader desires to assist others, with a strong sense of ideals guiding their actions. A notable example has been protagonist Kenshiro of the highly influential Fist of the North Star franchise. Known for his incorruptible nature and ironclad sense of determination as well as massive physical strength, the character has utilized a particular fighting style focusing on various pressure points in order to defeat his opponents while traveling through a landscape that nuclear warfare has devastated, Kenshiro serving as a violent kind of messianic archetype.[69] In the 2010s, the character's catchphrase "Omae Wa Mou Shindeiru" ("You Are Already Dead") became one a popular internet meme.[70]

The titular character behind the Sailor Moon franchise has gained notice for her altruism and assertive personality. Both her and the overall collection of media involving her have featured a dogged idealism through which emotionally positive values such as friendship and love win out against just about adversity.[71] Unusually for an animated production based around young middle-class women, the franchise's fandom notably has stood out for its diversity in terms of age, class, and gender.[citation needed]

Idealism in historical and modern printed media[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

Characters in stories still well known from classical antiquity for their idealistic actions and words include, for instance, Achilles. The heroic figure, a prominent part of stories such as the ancient Greek work the Iliad, has attracted notice for his immense courage and powerful sense of individual honor. Writing for CEC Critic, professor Thomas S. Kane has stated that Achilles' particular portrayal constitutes "idealism in an excessive, radical[,] and absolute way" that makes the character's actions in the Iliad essentially "sadomasochistic".[1]

The debate about the possible lack of goodness inherent in mankind and its capacity to hold to high-minded ideals is prominently displayed in The Grand Inquisitor, with the fictional confrontation between Jesus Christ and an outwardly Christian appearing leader who actually holds cynical views attracting great attention since its authorship by Fyodor Dostoevsky in 1880. While the titular inquisitor rationally argues for the relativist view that people seek safety and security over higher callings, Christ surprisingly kisses the aged, emotionally distant leader on the lips; while still holding to his views, the moved inquisitor allows Christ to leave freely. The ethical conflict posed by the characters' fundamental opposition, notably, fails to come to a resolution in the work, the ambiguity gaining much notice by later commentators.[72]

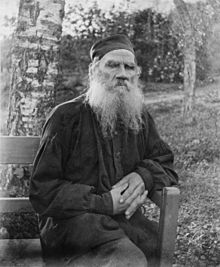

The material of Russian writer Leo Tolstoy have had massive influence within Eurasia and elsewhere. Working through his strident sense of religious ideals, his argumentative works notably include The Kingdom of God Is Within You. Possessing principles that put him at odds with the Russian Orthodox Church, which excommunicated him in a failed attempt to reduce his popularity, the author's bibliography additionally includes fictional works such as Anna Karenina and War and Peace.[73][74]

Multiple stories authored by Tolstoy set forth a deep ethical criticism of the mores of his day. In the novella The Death of Ivan Ilyich, for instance, the titular protagonist gets described as only truly understanding his place in the world and the meaning of his existence on his deathbed, the character realizing that the concerns he spent the vast majority of his time on such as the advancement of his career ultimately meant nothing. Tolstoy's idealism led him to abandon the regular living expected of such a prominent figure and to live on a commune in similar practice to the early Christians shortly after the death of Jesus; in both his fiction and other writings, he's molded the development of not only Christian ethics but other idealistic traditions as well.[citation needed]

"Tolstoy is a reflector as vast as a natural lake; a monster harnessed to his great subject— all human life," translator and writer Henry James famously remarked. Later figures influenced by Tolstoy's ideals notably include Indian independence activist and social leader Mahatma Gandhi.[74] Upon the author's later years, his status as a cultural icon meant that a worldwide collection of followers worked to apply his ideals.[73]

Comic books often incorporate conflicts between traditional heroes and heroines, ones who act out of a sense of altruism and cling to strict sets of ideals, with antiheroes and other morally ambiguous individuals that still feature prominent superpowers. A particular example that's attracted commentary is the tension between Superman,[75] one so bound by ideals he's been nicknamed the "big blue boy scout",[76] and groups such as the Elite, who face little qualms engaging in brutality. Discussing the animated film Superman vs. The Elite, an adaptation of a plot featured in the Action Comics story What's So Funny About Truth, Justice & the American Way?, one movie critic opined that Superman faced his worst nemesis of all in "public opinion", with a cynical populace finding it harder in a terrorism-influenced world to support an advocate of "idealistic optimism".[75]

Other characters of a similar type include Nightwing, with a commentator remarking that "while Batman fights in the name of vengeance, Nightwing does it because it’s the right thing to do."[77] Different comics have explored the contrast between Nightwing's idealism and the views of Batman, the former figure's mentor, given that the latter figure possess a far more jaded nature with a particular lack of trust. Thus, while teaming up on multiple occasions, Nightwing in contrast to Batman has felt comfortable fighting in a team to accomplish larger, altruistic goals and additionally has expressed his willingness to share his civilian alter ego with others.[78]

In the context of European comics, the Adventures of Tintin original series and related media, originally created by Belgian cartoonist Hergé, has featured a protagonist in foreign correspondent Tintin regarded by publications such as The Guardian as "[b]roadly speaking... Herge's ideal self", the character serving as "the perfect boy scout" in being "idealistic, brave, [and] pure-hearted". The publication has recommended three particular Tintin stories within its project titled 1000 Novels Everyone Must Read.[79] French statesman Charles de Gaulle notably remarked that "my only international rival is Tintin" since they had both been "the little guys who refuse to let the big guys walk all over us."[80]

Idealism in music and other material[edit]

Overview of idealism in music[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

In the history of recorded music, a great many albums and songs have been distributed with an idealistic kind of emotional tone. Such material has often featured lyrics emphasizing psychologically positive and assuring themes, examples being compassion, faith, forgiveness, generosity, and so on. In terms of instrumental work, said music additionally has frequently featured upbeat sounds meant to provide a melodramatic undercurrent, the musicians having intended feelings of contentment, joy, victory, et cetera. Idealistic material has gotten released across multiple genres from heavy metal to jazz to light rock to pop and more.[citation needed]

Although idealistic lyrical content has been usually considered to exist in tandem with the rest of a given song, it has additionally not been uncommon for that not to be the case. Prominent examples exist of light-sounding vocals accompanying a dark-sounding background and vice versa. Labeling particular material as being notably idealistic within the broader market for recorded music has been a broad subject, praising commentary for various releases having been written in a variety of different social environments.[citation needed]

The straight edge movement and related sub-genres of punk rock have particularly attracted much attention in this context. Fans of positive hardcore specifically have been known for promoting song lyrics emphasizing camaraderie and a shared sense of purpose. Examples of the idealist hardcore sound include the bands 7 Seconds and Youth of Today. Within this particular strain of the larger punk movement, music has been used as inspiration to reject the broader sense of hedonism among rock groups, with causes such as fighting against racism, opposition to war, and raising funds for charity getting emphasized. The ideal of unity in the face of adversity has been a core principle of the scene.[81]