University of Edinburgh

Scottish Gaelic: Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Latin: Universitas Academica Edinburgensis | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Public university/ancient university | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Established | 1583[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Endowment | £459.9 million (as of 31 July 2019)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Budget | £1.081 billion (university); £1.102 billion (consolidated) (2018-19)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Chancellor | Anne, Princess Royal | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Rector | Ann Henderson | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Principal | Peter Mathieson | ||||||||||||||||||||

Academic staff | 4,589 FTE[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||

Administrative staff | 6,107 FTE [3] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Students | 34,275 (2018-19) [4] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Undergraduates | 22,750 [4] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Postgraduates | 11,525 [4] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | , | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Campus | Urban | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Colours | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Affiliations | Alan Turing Institute Coimbra Group EUA LERU Russell Group UNA Europa UNICA Universitas 21 Universities Scotland Universities UK | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | www | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

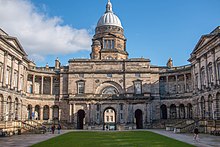

The University of Edinburgh (abbreviated as Edin. in post-nominals), founded in 1582,[1] is the sixth oldest university in the United Kingdom and English-speaking world and one of Scotland's ancient universities. The university has five main campuses in the city of Edinburgh, which include many buildings of historical and architectural significance such as those in Old Town.[5] The university played an important role in Edinburgh becoming a chief intellectual centre during the Scottish Enlightenment, contributing to the city being nicknamed the "Athens of the North".

The university is a member of a number of prestigious academic organisations, including the Russell Group, the Coimbra Group, the Universitas 21, and the League of European Research Universities, a consortium of 23 leading research universities in Europe. It has the third largest endowment of any university in the United Kingdom, after the universities of Cambridge and Oxford. In 2018-19, the university has a consolidated annual income of £1,101.6 million, of which £285.7 million was from research grants and contracts, with a total expenditure of £1,236.1 million.[2]

The alumni of the university include some of the major figures of modern history, including three signatories of the United States Declaration of Independence and nine heads of state and government (including three Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom). As of 2020, Edinburgh's alumni, faculty members and researchers include 19 Nobel laureates, three Turing Award laureates, an Abel Prize winner and Fields Medalist, two Pulitzer Prize winners, two currently sitting UK Supreme Court Justices, and several Olympic gold medallists.[6] It continues to have links to the British Royal Family, having had the Duke of Edinburgh as its Chancellor from 1953 to 2010 and Princess Anne since 2011.[7]

Edinburgh receives approximately 60,000 applications every year, making it the second most popular university in the United Kingdom by volume of applications.[8] It has the 4th-highest average UCAS entry tariff in Scotland, and 8th overall in the United Kingdom.[9]

History[edit]

Founding[edit]

Founded by the Edinburgh Town Council, the university began life as a college of law using part of a legacy left by a graduate of the University of St Andrews, Bishop Robert Reid of St Magnus Cathedral, Orkney.[10] Through efforts by the council and ministers of the city, such as John Knox's successor James Lawson, the institution broadened in scope and became formally established as a college by a Royal Charter, granted by King James VI on 14 April 1582.[1][11] This was unprecedented in newly Presbyterian Scotland, as older universities in Scotland had been created through Papal bulls.[12] Established as the "Tounis College", it opened its doors to students in October 1583.[1] Instruction began under the charge of another St Andrews graduate, theologian Robert Rollock.[10] It was the fourth Scottish university in a period when the richer and much more populous England had only two. The school was renamed King James's College in 1617. By the 18th century, the university was a leading centre of the Scottish Enlightenment.

Development[edit]

In 1762, Reverend Hugh Blair was appointed by King George III as the first Regius Professor of Rhetoric and Belles-Lettres. This formalised literature as a subject at the university and the foundation of the English Literature department, making Edinburgh the oldest centre of literary education in Britain.[13]

Before the building of Old College by architect William Henry Playfair to plans by Robert Adam, the University of Edinburgh existed in a hotchpotch of buildings from its establishment until the early 19th century. The university's first custom-built building was Old College, now home to Edinburgh Law School, situated on South Bridge. The South Bridge Act 1785 was passed in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom on 21st April 1785 for rebuilding or improving the University. Its first forte in teaching was anatomy and the developing science of surgery, from which it expanded into many other subjects. Bodies to be used for dissection were brought to the university's anatomy lecture theatre through a secret tunnel from the basement of a nearby house (today's College Wynd student accommodation). It was also through this tunnel that the victims of murderers William Burke and William Hare were delivered in the 1820s, and so was the body of Burke himself after his execution in 1829.[14]

Towards the end of the 19th century, Old College was becoming overcrowded and Sir Robert Rowand Anderson was commissioned to design new premises for the Medical School in 1875. Initially, the design incorporated a graduation hall, but this was seen as too ambitious. After funds were donated by brewer and politician Sir William McEwan in 1894, a separate graduation building was constructed after all, also designed by Anderson. The resulting McEwan Hall was presented to the University in 1897.

New College was originally opened in 1846 as a Free Church of Scotland college, later of the United Free Church of Scotland. Since the 1930s it has been the home of the School of Divinity. Prior to the 1929 reunion of the Church of Scotland, candidates for the ministry in the United Free Church studied at New College, whilst candidates for the old Church of Scotland studied in the Divinity Faculty of the University of Edinburgh. During the 1930s the two institutions came together, sharing the New College site on The Mound.[15]

By the end of the 1950s, there were around 7,000 students matriculating annually.[16]

A Students' Representative Council (SRC) was founded in 1884 by student Robert Fitzroy Bell.[17] In 1889, the SRC voted to establish a union (the Edinburgh University Union, EUU), to be housed in Teviot Row House. Edinburgh University Sports Union (EUSU) was founded in 1866, and the Edinburgh University Women's Union in 1906. On 1 July 1973 the SRC, EUU and Chambers Street Union merged to form Edinburgh University Students' Association (EUSA).[18]

Medical school[edit]

Edinburgh's Medical School is renowned throughout the world. It was widely considered the best medical school in the English-speaking world throughout the 18th century and first half of the 19th century.[19]

The Edinburgh Seven were the first group of matriculated undergraduate female students at any British university. Led by Sophia Jex-Blake, they began studying medicine at the University of Edinburgh in 1869. Although they were unsuccessful in their struggle to graduate and qualify as doctors, their campaign gained national attention and won them many supporters including Charles Darwin. Their efforts put the rights of women to university education on the national political agenda, which eventually resulted in legislation to ensure women could study at university in 1877. The University of Edinburgh admitted women to graduate in medicine in 1894.[20] In 2015, the Edinburgh Seven were commemorated with a plaque at the University.[21]

The Polish School of Medicine was established in 1941 as "a wartime testament to this spirit of enlightenment". Students were to be those drawn from the Polish army to Britain and were taught in Polish. When the school was closed in 1949, 336 students had matriculated, of which 227 students graduated with the equivalent of an MBChB. A total of 19 doctors obtained a doctorate or MD. A bronze plaque commemorating the existence of the Polish School of Medicine is located in the Quadrangle of the Medical School in Teviot Place.[22]

The Little France campus, including the Chancellor's Building, was opened on 12 August 2002 by the Duke of Edinburgh. The campus houses the Medical School on the site of the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh.[23]

2000 to present[edit]

The Edinburgh Cowgate Fire of December 2002 destroyed a number of university buildings, including some 3,000 m2 (30,000 sq ft.) of the School of Informatics at 80 South Bridge.[24] This was replaced with the Informatics Forum on the central campus, completed in July 2008.

The Edinburgh Cancer Research Centre (ECRC) was opened in 2002 by The Princess Royal on the Western General Hospital site.[25] In 2007, the MRC Human Genetics Unit formed a partnership with the Centre for Genomic and Experimental Medicine and the Edinburgh Cancer Research Centre to create the Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine (IGMM).[26]

The Euan MacDonald Centre was established in 2007 as a research centre for motor neuron disease (MND). The centre was part funded by a donation from Scottish entrepreneur Euan MacDonald and his father Donald.[27][28]

On 1 August 2011, the Edinburgh College of Art (founded in 1760) merged with the university's School of Arts, Culture and Environment.[29]

The Scottish Centre for Regenerative Medicine, a stem cell research centre dedicated to the development of regenerative treatments, was opened by the Anne, Princess Royal on 28 May 2012.[30] It is home to biologists and clinical academics from the MRC Centre for Regenerative Medicine (CRM), and applied scientists working with the Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service and Roslin Cells.[31] On 25 August 2014, the centre reported on the first working organ, a thymus, grown from scratch inside an animal.[32]

In 2014, the Zhejiang University-University of Edinburgh Institute was founded as a joint institute offering degrees in biomedical sciences, taught in English. The campus, located in Haining, Zhejiang Province, China, opened on 16 August 2016.[33]

Beginning in 2015, the University of Edinburgh maintains a Wikimedian in Residence.[34]

In 2018, the University of Edinburgh was a signatory in the landmark £1.3bn Edinburgh and South East Scotland City Region Deal[35], with the UK and Scottish governments, six local authorities and all universities and colleges in the region. The University committed to delivering a range of economic benefits to the region through the Data-Driven Innovation initiative. In conjunction with Heriot-Watt University, the initiative created four innovation hubs - the Bayes Centre, Usher Institute, Edinburgh Futures Institute, Easter Bush Campus, and one based at Heriot-Watt, the National Robotarium. The deal also included creation of the Edinburgh International Data Facility, which performs high-speed data processing in a secure environment.[36][37]

Campuses[edit]

The university has five main sites in Edinburgh: Central, King's Buildings, BioQuarter, Western General, Easter Bush.[38]

The university is responsible for a number of historic and modern buildings across the city, including Scotland's oldest purpose-built concert hall, and the second oldest in use in the British Isles, St Cecilia's Hall; Teviot Row House, which is the oldest purpose-built student union building in the world; and the restored 17th-century Mylne's Court student residence which stands at the head of Edinburgh's Royal Mile.

Central area[edit]

The Central campus is spread around numerous squares and streets in Edinburgh's Southside, with some buildings in Old Town. It is the university's oldest area, occupied primarily by the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, the School of Computing, and the School of Law. The highest concentration of university buildings is around George Square, which includes the Central campus' largest lecture hall, the Gordon Aikman Lecture Theatre, Edinburgh University Library, and the Appleton Tower and 40 George Square[39] teaching and administrative buildings. Around nearby Bristo Square lie the Dugald Stewart Building, the Informatics Forum, McEwan Hall, Teviot Row House, and the old Medical School buildings in Teviot Place, which still house pre-clinical medical courses and biomedical sciences despite the relocation of the Medical School to Little France. The main EUSA buildings of Potterrow, Pleasance and Teviot are located near the Central area, as is the Edinburgh College of Art in Lauriston Place. North of George Square lies the university's Old College housing the School of Law, St Cecilia's Hall, and the School of Divinity's New College on The Mound. Some of these buildings are used to host events during the Edinburgh International Festival every summer.

Pollock Halls[edit]

Pollock Halls, adjoining Holyrood Park to the east, provides accommodation (mainly half board) for a minority of students in their first year. Two of the older houses in Pollock Halls were demolished in 2002 and a new building (Chancellor's Court) has been built in their place, leaving a total of ten buildings. Self-catered flats elsewhere account for the majority of university-provided accommodation. The area also includes a £9 million redeveloped John McIntyre Conference Centre, which is the University's premier conference space.

Holyrood (Moray House)[edit]

The Moray House School of Education and Sport,[40] just off the Royal Mile, used to be the Moray House Institute for Education until this merged with the University in August 1998. The University has since extended Moray House's Holyrood site.[41] The buildings include redeveloped and extended Sports Science, Physical Education and Leisure Management facilities at St Leonard's Land linked to the Sports Institute in the Pleasance.[42] The 2016 Holyrood North halls have been named after former principal Sir Timothy O'Shea and further student accommodation is provided at Holyrood South.[43][44][45] The Outreach Centre, Institute for Academic Development (University Services Group) and the Edinburgh Centre for Professional Legal Studies (School of Law) are also located at Holyrood.[46][47][48]

King's Buildings[edit]

The King's Buildings (KB) campus is located in the south of the city. Most of the Science and Engineering College's research and teaching activities take place at the King's Buildings, which occupy a 35-hectare site. It includes C. H. Waddington Building (the Centre for Systems Biology at Edinburgh), James Clerk Maxwell Building (the administrative and teaching centre of the School of Physics and Astronomy and the School of Mathematics), The Royal Observatory, William Rankine Building (School of Engineering's Institute for Infrastructure and Environment) and others. Until 2012, the King's Buildings campus was served by three libraries: Darwin Library, James Clerk Maxwell Library, and Robertson Engineering and Science Library. These were replaced by the Noreen and Kenneth Murray Library opened for the 2012/13 academic year. The KB also hosts the National e-Science Centre (NeSC), Scottish Microelectronics Centre (SMC), Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre (SUERC), and the Scottish Institute for Enterprise.

BioQuarter[edit]

BioQuarter, south of Edinburgh is home to the majority of medical facilities of the university, alongside the city's hospital - the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. At Little France, the £40 million Chancellor's Building was opened on 12 August 2002 by the Duke of Edinburgh, which houses the Medical School at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. The building was a joint project between private investors, local authorities and the University to create a large modern hospital, veterinary clinic and research institute. It has two large lecture theatres and a medical library. It is connected to the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh by a series of corridors. Queen's Medical Research Institute was opened in 2005 and provides facilities for research into the understanding of common diseases.

Easter Bush[edit]

The Easter Bush campus houses the Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, The Roslin Institute, Jeanne Marchig International Centre for Animal Welfare Education, and the Veterinary Oncology and Imaging Centre.

The Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, founded in 1823 by William Dick, is a world leader in veterinary education, research and practice. Its new 11,500 square metre building opened in 2011.

The Roslin Institute is an animal sciences research institute which is sponsored by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.[49] The Institute won international fame in 1996, when its researchers Ian Wilmut, Keith Campbell and their colleagues created Dolly the sheep, the first mammal to be cloned from an adult cell.[50][51] A year later Polly and Molly were cloned; both sheep contained a human gene.

Western General[edit]

The Western General Hospital campus contains the Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility, and Clinical Neuroscience.

- Modern architecture at the University of Edinburgh

Evolution House, Edinburgh College of Art

Organisation and administration[edit]

The University Court is the University's governing body and is the legal persona of the University. By the Universities (Scotland) Act 1889, the University Court is a body corporate, with perpetual succession and a common seal; and all the property belonging to the University at the passing of the Act was vested in the Court.

In 2002, the university was reorganised from its nine faculties into three "colleges". While technically not a collegiate university, it now comprises the Colleges of Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS), Science & Engineering (SCE) and Medicine & Vet Medicine (MVM). Within these colleges are "schools" – roughly equivalent to the departments they succeeded; individual schools have a good degree of autonomy regarding their finances and internal organisation. This has brought a certain degree of uniformity (in terms of administration at least) across the university.

Colleges and schools[edit]

Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences[edit]

The College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences[52] is the largest of the three Colleges in the University of Edinburgh. It has 11 Schools, one Centre, 25,185 students and 1,501 academic staff.[53] An advantage of its size is the very wide range of subjects and research specialisms. There are over 300 undergraduate, 200 taught postgraduate programmes and over 2,200 PhD students. Its research strength, as affirmed in the 2008 RAE, has attracted over 1,200 researchers.[54] It includes the oldest English Literature department in Britain.[13] It was ranked 12th in the world according to the Times Higher Education 2014–15 Ranking. The college hosts Scotland's Economic & Social Research Council Doctoral Training Centre (DTC): The Scottish Graduate School of Social Science is the biggest of 21 ESRC-accredited DTC's in the United Kingdom.

- Business School

- Edinburgh College of Art

- Moray House School of Education

- School of Divinity

- School of Economics

- School of Health in Social Science

- School of History, Classics and Archaeology

- School of Law

- School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures

- School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences

- School of Social and Political Science

- The Centre for Open Learning

- The Urban Institute

Medicine and Veterinary Medicine[edit]

The College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine has a long history as one of the best medical institutions in the world.[55] In the last research assessment exercise, it was rated 1st in the UK for medical research submitted to the Hospital-based Clinical Subjects Panel. All of the work was rated at International level and 40% at the highest, "world-leading" level.[56] The medical school is ranked 1st in Scotland and 3rd in the UK by The Times Good University Guide 2013, The Complete University Guide 2013 and The Guardian University Guide 2013.[57][58]

Graduates of the University of Edinburgh Medical School have gone on to found five out of the seven Ivy League medical schools, become US Senators, become Prime Minister of Canada, invent the hypodermic syringe, cure scurvy, discover carbon dioxide and isolate nitrogen, develop IV therapy, invent the decompression chamber, develop the oophorectomy, and discover the SARS virus. Faculty of the University of Edinburgh Medical School have introduced antiseptic to sterilize surgical instruments, discovered chloroform anesthesia, discovered oxytocin, developed the Hepatitis B vaccine, co-founded Biogen, pioneered treatment for tuberculosis, discovered apoptosis and tyramine among others.

The eight original faculties formed four Faculty Groups in August 1992. Medicine and Veterinary Medicine became one of these, and in September 2002, became the smallest of the university's three Colleges, with 7,250 students and 1,615 academic staff.[53]

- University of Edinburgh Medical School

- Royal School of Veterinary Studies

- School of Biomedical Sciences

- School of Clinical Sciences and Community Health

Science and Engineering[edit]

In the sixteenth century science was taught as 'natural philosophy'. The seventeenth century saw the institution of the University Chairs of Mathematics and Botany, followed the next century by Chairs of Natural History, Astronomy, Chemistry and Agriculture. During the eighteenth century, the University was a key contributor to the Scottish Enlightenment and it educated many of the most notable scientists of the time. It was Edinburgh's professors who took a leading part in the formation of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1783. In 1785, Joseph Black, Professor of Chemistry and discoverer of carbon dioxide, founded the world's first Chemical Society.[59] The nineteenth century was a time of huge advances in scientific thinking and technological development. The first named degrees of Bachelor and Doctor of Science was instituted in 1864, and a separate 'Faculty of Science' was created in 1893 after three centuries of scientific advances at Edinburgh.[59] The Regius Chair in Engineering was established in 1868, and the Regius Chair in Geology in 1871. In 1991 the Faculty of Science was renamed the Faculty of Science and Engineering, and in 2002 it became the College of Science and Engineering. The college has 11,445 undergraduate and postgraduate students, and 1,455 academic staff.[53]

- School of Biological Sciences

- School of Chemistry

- School of Engineering

- School of GeoSciences

- School of Informatics

- School of Mathematics

- School of Physics and Astronomy

Academic profile[edit]

All teaching is now done over two semesters (rather than 3 terms) – bringing the timetables of different Schools into line with one another, and coming into line with many other large universities (in the US, and to an increasing degree in the UK as well).[citation needed]

The University of Edinburgh is a member of the Russell Group of research-led British universities and one of several British universities to be a member of both the Coimbra Group and the LERU (League of European Research Universities). The university is also a member of Universitas 21, an international association of research-led universities. Edinburgh is a member of the 'Sutton 13' of top-ranked Universities in the UK.[60] Beside, the university maintains historically strong ties with the neighbouring Heriot-Watt University for teaching and research.

Moreover, the University of Edinburgh has around 300 student exchange partners in nearly 40 countries world-wide including exchange programs with Peking University, Washington University in St. Louis, Karolinska Institute, and Caltech.[61]

Admissions[edit]

| 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applications[62] | 62,480 | 61,650 | 59,255 | 55,060 | 50,750 |

| Offer Rate (%)[63] | 50.4 | 48.6 | 49.2 | 45.9 | 44.3 |

| Enrols[64] | 6,800 | 6,250 | 6,185 | 5,780 | 5,490 |

| Yield (%) | 21.6 | 20.9 | 21.2 | 22.9 | 24.4 |

| Applicant/Enrolled Ratio | 9.19 | 9.86 | 9.58 | 9.53 | 9.24 |

| Average Entry Tariff[65][a] | 189 | 180 | 483 | 485 | 482 |

As of 2019, Edinburgh had the 8th highest average entry qualification for undergraduates among UK universities, with new students averaging 189 UCAS points,[9] equivalent to just above AAAaa in A-level grades. The university gives offers of admission to 20% of its 18 year old applicants, the 5th lowest amongst the Russell Group.[66]

As the number of places available for Scottish and EU students are capped by the Scottish Government since students do not pay tuition fees, students applying from the UK and outside of the European Union have a higher likelihood of an offer.[67] Excluding courses within the Edinburgh College of Art, the most competitive courses for Scottish/EU applicants in 2016 were International Relations, Oral Health Sciences and Business Studies with offer rates of 7%, 8% and 9% respectively.[68] In comparison, students from the rest of the UK have a 55% chance of receiving an offer for International Relations[69] and students from outside of the EU have a 79% chance of an offer for International Relations.[70]

33.6% of Edinburgh's undergraduates are privately educated, the seventh highest proportion amongst mainstream British universities.[71] As of the end of 2016, the university has a higher proportion of female than male students with a male to female ratio of 39:61 in the undergraduate population. The undergraduate student body is composed of 37% Scottish students, 31% from the rest of the UK, 11% from the EU and 20% from outside of the EU.[72]

Rankings and reputation[edit]

| National rankings | |

|---|---|

| Complete (2021)[73] | 15 |

| Guardian (2021)[74] | 13 |

| Times / Sunday Times (2021)[75] | 17 |

| Global rankings | |

| ARWU (2020)[76] | 42 |

| QS (2021)[77] | 20 |

| THE (2021)[78] | 30 |

In the 2014 UK Research Excellence Framework, Edinburgh was ranked fourth in the UK and first in Scotland. The results also indicate that the university is home to over 35% of Scotland's 4* research.[79] In 2008, the RAE rated the medicine and informatics 1st in the UK.[80] Edinburgh places within the top 10 in the UK and 2nd in Scotland for the employability of its graduates as ranked by recruiters from the UK's major companies.[81] A 2015 government report found that Edinburgh is one of only two Scottish universities (along with St Andrews), London-based recruitment and elite professions such as investment banking consider applicants from.[82] Edinburgh was ranked 13th overall in The Sunday Times 10-year average (1998–2007) ranking of British universities based on consistent league table performance.[83]

The QS World University Rankings 2020 ranked Edinburgh 20th in the world. The Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2020 ranked Edinburgh 30th in the world. In 2020, the Academic Ranking of World Universities placed Edinburgh as 42nd overall and 6th in the UK. Edinburgh was ranked 37th in the world (6th in the UK) in the 2020 Round University Ranking.[84] In 2020, it ranked 66th among the universities around the world by SCImago Institutions Rankings.[85]

The noticeable disparity between the University of Edinburgh's research capacity, endowment and international status on the one hand, and its ranking in national league tables on the other, is largely on account of the central role which 'student satisfaction' plays in the latter.[86] The University of Edinburgh was ranked bottom in the UK for teaching quality by its students in the 2012 National Student Survey.[87][88][89] According to The Times and Sunday Times Good University Guide 2015, "The university is trying to address undergraduates' concerns with a new personal tutor system and a peer support scheme. However, Edinburgh achieved an unwanted clean sweep of rock bottom rankings among universities in this year's National Student Survey (NSS) for questions to do with the promptness, usefulness and extent of academic feedback, suggesting the university still has a long way to go to turn around a poor position".[90] In the 2017 guide, Edinburgh fell to its worst-ever position of joint 37th (placed with local Heriot-Watt University) in a domestic league table. The fall was attributed to lower NSS scores combined with a significant drop (78.6% to 73%) in the prospects of its graduates.[91]

In the 2016 Complete University Guide, 19 out of the 50 subjects offered by Edinburgh rank within the top 10 nationally,[92] with Architecture, Chemical Engineering, East and South Asian Studies, Linguistics, Middle Eastern and African Studies, Social Policy and Veterinary Medicine occupying the top five positions.[93] The 2020 Times Higher Education World University Rankings listed Edinburgh in 36th place worldwide for social sciences.[94]

Student life[edit]

Students' Association[edit]

The Edinburgh University Students' Association (EUSA) consists of the unions and the Student Representative Council. The union buildings include Teviot Row House, Potterrow, Kings Buildings House, the Pleasance, and shops, cafés and refectories across the various campuses. Teviot Row House is claimed to be the oldest purpose-built student union building in the world.[95] EUSA represents students to the university and the outside world. It is also responsible for over 250 student societies at the University. The association has five sabbatical office bearers – a president and four vice presidents. The association is affiliated to the National Union of Students.

Performing arts[edit]

The city of Edinburgh is an important cultural hub for comedy, amateur and fringe theatre throughout the UK. Amateur dramatic societies at the University benefit from this, and especially from being based in the home of the Edinburgh Fringe Festival.[96]

Edinburgh University Theatre Company (EUTC), founded in 1896 as the Edinburgh University Drama Society, is known for running Bedlam Theatre, the oldest student-run theatre in Britain. Bedlam Theatre is an award-winning Edinburgh Fringe venue.[97] The EUTC also fund and run acclaimed[98] student improvised comedy troupe The Improverts during term time and fringe.[99] Alumni include Ian Charleson, Michael Boyd, Kevin McKidd, and Greg Wise.

Edinburgh Studio Opera (formerly Edinburgh University Opera Club) is the only student opera company in Edinburgh. The group performs at least one fully staged opera each year.

The Edinburgh University Savoy Opera Group (EUSOG) are an opera/musical theatre company founded by students in 1961 to promote and perform the comic operettas of William Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan,[100] collectively known as Savoy Operas after the theatre in which they were originally staged.

The Edinburgh University Footlights are a musical theatre company founded in 1989 and produce two large scale shows a year.

Theatre Parodok, founded in 2004, is a student theatre company that aims to produce shows that are "experimental without being exclusive". They produce a large show each semester and one for the festival.[101][102]

Media[edit]

The Student is a weekly Scottish newspaper produced by students at the University of Edinburgh. Founded in 1887, it is the oldest student newspaper in the United Kingdom.[citation needed]

The Journal was an independent publication, established in 2007 by three students at the University of Edinburgh, and was also distributed to the four other higher education institutions in the city – Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh Napier University, Queen Margaret University and the Edinburgh College of Art. It was the largest such publication in Scotland, with a print run of 14,000 copies and was produced by students from across the city. It folded in 2015.[103]

Fresh Air is an alternative music student radio station, one of the oldest surviving student radio stations in the UK. It was founded in October 1992.[citation needed]

In September 2015, Edinburgh University Student Television (EUTV) became the newest addition to the student media scene at the university, producing a regular magazine styled programme, documentaries and other special events.[104]

Sport[edit]

Edinburgh University's student sport consists of 67 clubs from the traditional rugby, football, rowing and Judo to the more unconventional Korfball and gliding. Over 67 sports clubs are run by the Edinburgh University Sports Union. The Scottish Varsity, known as the "world's oldest varsity match", is a rugby match played annually against the University of St Andrews.[105] It is played at the beginning of the academic year and since 2015 it has been played at Murrayfield Stadium in Edinburgh.[106]

During the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, the University of Edinburgh alumni and students secured four medals – three gold and a silver. The three gold medals were won by the cyclist Chris Hoy and the silver was won by Katherine Grainger in rowing.

In the 2012 Summer Olympics Edinburgh University Alumni topped the UK University Medals table with three gold medals, two from Chris Hoy and one from Katherine Grainger.[107]

Student activism[edit]

There are a number of campaigning societies at the university. The largest of these include the environment and poverty campaigning group People & Planet and the Amnesty International Society. International development organisations include Edinburgh Global Partnerships, which was established as a student-led charity in 1990. There is also a significant left-wing presence on campus,[108] including an active anti-cuts group, an anarchist society, Edinburgh University Socialist Society, Marxist Society, feminist society, Young Greens, a Students for Justice in Palestine group, and the Edinburgh University Conservative and Unionist Association.[109][110] Protests, demonstrations and occupations are regular occurrences at the university.[111][112][113]

The activist group People and Planet took over Charles Stewart House in 2015 and again in 2016 in protest over the Universities investment in Arms and Fossil fuels[114][115] In May 2015, a security guard was charged in relation to the occupations.[116]

Student co-operatives[edit]

There are three student-run co-operatives on campus: Edinburgh Student Housing Co-operative, providing affordable housing for 106 students;[117] The Hearty Squirrel Food Cooperative, selling 'healthy, local, ethical, organic and Fairtrade' food;[118] and the SHRUB Co-op, a 'swap and re-use hub' aimed at reducing waste and promoting sustainability.[119] The co-operatives form part of the Students for Cooperation network.[120]

Library[edit]

The Edinburgh University Library pre-dates the university by three years. Founded in 1580 through the donation of a large collection by Clement Littill, its collection has grown to become the largest university library in Scotland with over 2.5 million volumes.[121] These are housed in the main University Library building in George Square – one of the largest academic library buildings in Europe, designed by Basil Spence.

The library system also includes many faculty and collegiate libraries.

Notable alumni and academic staff[edit]

The university is associated, through alumni and academic staff, with some of the most significant intellectual and scientific contributions in human history. As of March 2019[update], 19 Nobel laureates have been affiliated with the university as alumni, faculty and researchers (three additional laureates acted as administrative staff), including one of the fathers of quantum mechanics Max Born, theoretical physicist Peter Higgs, supramolecular chemist Sir Fraser Stoddart, biophysicist Richard Henderson, and pioneer of in-vitro fertilisation Robert Edwards. Computer scientists Robin Milner and Leslie Valiant, both Turing Award laureates, and mathematician Sir Michael Atiyah, Fields Medallist and Abel Prize winner, are associated with the university.

The university is further associated with scientists whose contributions include: laying the foundations of Bayesian statistics (Thomas Bayes), nephrology (Richard Bright), the theory of evolution (Charles Darwin), the initial development of sociology (Adam Ferguson), modern geology (James Hutton), antiseptic surgery (Joseph Lister), the classical theory of electromagnetism (James Clerk Maxwell), and thermodynamics (William John Macquorn Rankine); the discovery of carbon dioxide, latent heat and specific heat (Joseph Black), the HPV vaccine (Ian Frazer), the Higgs mechanism (Peter Higgs and Tom Kibble), the Hepatitis B vaccine (Kenneth Murray), nitrogen (Daniel Rutherford), chloroform anaesthesia (James Young Simpson) and SARS (Nanshan Zhong); and the invention of the telephone (Alexander Graham Bell), the hypodermic syringe (Alexander Wood), the kaleidoscope (David Brewster), the telpherage (Fleeming Jenkin), the vacuum flask (James Dewar), the ATM (John Shepherd-Barron), and the diving chamber (John Scott Haldane).

Other notable alumni and academic staff of the university have included signatories to the US Declaration of Independence Benjamin Rush, James Wilson and John Witherspoon, Prime Ministers Gordon Brown, Lord Palmerston and Lord John Russell (the latter matriculated at Edinburgh, but did not graduate), actor Ian Charleson, astronaut Piers Sellers, biologist Ian Wilmut, botanist Robert Brown, chemist Alexander R. Todd, composers Marjory Kennedy-Fraser and Kenneth Leighton, economists Kenneth E. Boulding and James Mirrlees, editor Ella Carmichael, geologist William Edmond Logan, philosophers David Hume and Adam Smith, physicists Sir David Brewster, Peter Guthrie Tait and Sheila Tinney, pilot Eric Brown, polymath Thomas Young, surgeons James Barry and Gertrude Herzfeld, writers J.M. Barrie, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Aeneas Francon Williams, Sir Walter Scott and Robert Louis Stevenson, former Home Secretary and Chancellor of the Exchequer Sir John Anderson, Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville, and former director general of MI5 Stella Rimington.

Olympic Games gold medallists from the university include six-times Olympic champion cyclist Sir Chris Hoy, rower Katherine Grainger and runner Eric Liddell.

In 2020, Peter Sawkins – who studies Accounting and Finance – won The Great British Bake Off. He is the youngest winner and the first Scottish winner of the show.

James Barry, surgeon

Alexander Graham Bell, engineer and inventor

Joseph Black, chemist

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, writer

Charles Darwin, naturalist

David Hume, philosopher

James Hutton, geologist

James Clerk Maxwell, mathematical physicist

Viscount Palmerston, Prime Minister

Sir Walter Scott, novelist and poet

Robert Louis Stevenson, novelist

At graduation ceremonies, the Vice-Chancellor caps graduates with the Geneva Bonnet, a hat which legend says was originally made from cloth taken from the breeches of John Knox or George Buchanan. The hat was last restored in 2000, when a note from 1849 was discovered in the fabric.[122][123] In 2006, a University emblem taken into space by Piers Sellers was incorporated into the Geneva Bonnet.[124]

Heads of state and government[edit]

| State/Government | Leader | Office |

|---|---|---|

| John Russell, 1st Earl Russell | Prime Minister (1846–52 and 1865–66) | |

| Henry Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston | Prime Minister (1855–58 and 1859–65) | |

| William Walker | President of Nicaragua (1856–1857) | |

| Charles Tupper | Prime Minister of Canada (1 May 1896 – 8 July 1896) | |

| Jang Taek-sang | Prime Minister of South Korea (6 May 1952 – 6 October 1952) | |

| Yun Bo-seon | President of South Korea (1960–1962) | |

| Julius Nyerere | President of Tanzania (1964–1985) | |

| Hastings Banda | President of Malawi (1966–1994) | |

| Gordon Brown | Prime Minister (2007–2010) |

Notable honorary alumni[edit]

Since 1695 the University of Edinburgh has awarded honorary degrees to over 2,900 individuals.[125] The University of Edinburgh awards both honorary doctorate degrees (in all subjects including Medicine, Dental Surgery and Veterinary Medicine and Surgery) and honorary master's degrees.

Bill Gates (2006), Principal founder of Microsoft Corporation[126]

Louise Richardson (2018), Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford[127]

Justin Trudeau (2017), 23rd Prime Minister of Canada[130]

Michael D. Higgins (2015), 9th President of Ireland[131]

Alan Greenspan (2004), 13th Chair of the Federal Reserve[132]

A. P. J. Abdul Kalam (2013), 11th President of India[133]

Irina Bokova (2010), 9th Director-General of UNESCO[135]

Historical links[edit]

- Harvard University, an American Ivy League university, had its medical school founded by three surgeons, one of whom was Benjamin Waterhouse, an alumnus of Edinburgh Medical School.[136]

- Dalhousie University, Canadian U15 university, founded in 1818. In the early 19th century, George Ramsay, the ninth Earl of Dalhousie and Nova Scotia Lieutenant-Governor at the time, wanted to establish a Halifax college open to all, regardless of class or creed. The earl modeled the fledgling college after the University of Edinburgh, near his Scottish home.[137]

- McGill University, Canadian U15 university, founded in 1821, has strong Edinburgh roots and links to the University of Edinburgh as McGill's first (and, for several years, its only) faculty, Medicine, was founded by four physicians/surgeons, including Andrew Fernando Holmes and John Stephenson, who had trained in Edinburgh.[138][139]

- University of Pennsylvania, an American Ivy League university, has long-standing historical links with the University of Edinburgh, Penn's School of Medicine was founded by John Morgan, an Edinburgh medical graduate and was modeled after Edinburgh Medical School.[140][141]

- Princeton University, an American Ivy League university, had its academic syllabus and structure reformed along the lines of the University of Edinburgh and other Scottish universities by its sixth president John Witherspoon, an Edinburgh theology graduate.[142]

- The College of William & Mary, the second-oldest university in the US, was founded by Edinburgh graduate James Blair, who served as the college's founding president for fifty years.[143]

- Columbia University, an American Ivy League university, had its medical school founded by Samuel Bard, an Edinburgh medical graduate.

- University of Sydney, the first Australian university, was founded by Charles Nicholson, a physician and graduate of the University of Edinburgh Medical School.

- India, where during British rule many officers of the Imperial Civil Service (1858 to 1947) and Imperial Forest Service (1864 to 1935) were educated and trained at Edinburgh.[144]

See also[edit]

- Centre for the History of the Book

- Edinburgh University Press

- Edinburgh University Settlement

- Epistemics, a term for cognitive science coined in 1969 by the University of Edinburgh with the foundation of its School of Epistemics

- Gifford Lectures

- Institute for the Study of Science, Technology and Innovation

- James Tait Black Memorial Prize

- List of early modern universities in Europe

Notes[edit]

- ^ New UCAS Tariff system from 2016.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Hermans, Jos. M. M.; Nelissen, Marc (1 January 2005). Charters of Foundation and Early Documents of the Universities of the Coimbra Group. Leuven University Press. p. 42. ISBN 9058674746.

- ^ a b c "The University of Edinburgh Reports & Financial Statements for the year to July 2019" (PDF). University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Staff Headcount & Full Time Equivalent Statistics (FTE) as at September 2019". Human Resources, The University of Edinburgh. September 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ a b c "Student data". Higher Education Statistics Agency. 7 August 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ "University Heritage". Edinburgh World Heritage. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020.

- ^ "Alumni in history". The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ "New Chancellor elected". Ed.ac.uk. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ "The Times Good University Guide 2018: Most Applications". The Good University Guide. London. Retrieved 7 December 2017.(subscription required)

- ^ a b "Top UK University League Tables and Rankings 2019". Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ a b A Short History of the University of Edinburgh: 1556–1889. Horn, D. B. 1967.

- ^ Grant, Alexander (1884). The Story of the University of Edinburgh. London.

- ^ "The Origin Of Universities". Cwrl.utexas.edu. Archived from the original on 20 February 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ a b "About the Anniversary | 250th Anniversary of English Literature | English Literature". Ed.ac.uk. 18 October 2011. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ "University of Edinburgh - Self-guided tour" (PDF). University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ Brown, Stewart J. (1996). "The Disruption and the Dream: The Making of New College 1843–1861". In Wright, David F.; Badcock, Gary D. (eds.). Disruption to Diversity: Edinburgh Divinity 1846-1996. Edinburgh: T&T Clark. pp. 29–50. ISBN 978-0567085177.

- ^ "Edinburgh's student roll now 7,400". The Glasgow Herald. 5 October 1960. p. 6. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ Wintersgill, Donald. "Bell, Robert Fitzroy (1859–1908)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/100753. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Catto, Iain (1989). 'No spirits and precious few women' - Edinburgh University Union - 1889-1989. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Union. p. 120.

- ^ Eddy, Matthew Daniel (2008). The Language of Mineralogy: John Walker, Chemistry and the Edinburgh Medical School, 1750–1800. London: Ashgate.

- ^ McCullins, Darren (16 November 2018). "Blazing a trail for first women doctors". BBC News.

- ^ "'Edinburgh Seven' honoured with plaque". BBC News. 10 September 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ "The Polish School of Medicine at the University of Edinburgh (1941–1949)". University of Edinburgh. 9 April 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ "Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh from The Gazetteer for Scotland". www.scottish-places.info. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ^ Gerard Seenan (9 December 2002). "Fire devastates Edinburgh's Old Town". The Guardian.

- ^ "Royal launch for cancer centre". BBC. 6 December 2002. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "Experts join up for cancer fight". BBC. 26 November 2007. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ Donnelly, Brian. "Hotel chain's founder gives cash for motor neurone centre". The Herald. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ "Motor neurone sufferer gives £1m to create research centre". The Scotsman. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ "Introduction | ECA Merger | Edinburgh College of Art". Ed.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ^ "Princess Royal opens Scottish Centre for Regenerative Medicine". BBC News. BBC. 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Scottish Centre for Regenerative Medicine". Regenerative Medicine. Health Science Scotland. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ Freeman, David (25 August 2014). "Scientists Create Working Organ From Scratch For First Time Ever". Huffington Post. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ Morris, Bridget. "Edinburgh University teams up with Chinese in joint campus venture". Herald Scotland.

- ^ "University of Edinburgh – Wikimedian in Residence".

- ^ "The Edinburgh and South East Scotland City Region Deal". acceleratinggrowth.org.uk. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "Edinburgh's city deal bets £791m on technology". www.newstatesman.com.

- ^ Kemp, Kenny (19 December 2018). "First tranche of Edinburgh City Region deal investment unveiled". businessInsider.

- ^ "Campus Maps". Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Equality, Diversity and Inclusion - an update". The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ "Moray House School of Education and Sport". The University of Edinburgh.

- ^ "Holyrood Campus – buildings and opening hours". The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "St Leonard's Land building profile". The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Halls given royal seal of approval". The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Property". Accommodation Catering and Events, The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Property". Accommodation Catering and Events, The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Outreach Centre building profile". The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Institute for Academic Development". University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Edinburgh Centre for Professional Legal Studies". www.law.ed.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "The Roslin Institute (University of Edinburgh) – Home Page". Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ^ Campbell, K. H. S.; McWhir, J.; Ritchie, W. A.; Wilmut, I. (1996). "Sheep cloned by nuclear transfer from a cultured cell line". Nature. 380 (6569): 64–66. Bibcode:1996Natur.380...64C. doi:10.1038/380064a0. PMID 8598906. S2CID 3529638.

- ^ Firn, D. (1999). "Roslin Institute upset by human cloning suggestions". Nature Medicine. 5 (3): 253. doi:10.1038/6449. PMID 10086368. S2CID 41278352.

- ^ "College renamed to reflect growth in arts | The University of Edinburgh". www.ed.ac.uk. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ a b c "Student figures" (PDF). Governance & Strategic Planning, The University of Edinburgh. 7 August 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ "About the College". Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ "College Overview". Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ "College Today". Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ "University guide 2013: league table for medicine". The Guardian. London. 22 May 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ "Medicine – Top UK University Subject Tables and Rankings 2013". Complete University Guide. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ a b "About the College". Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ "Old school 'key to student place'". BBC. 20 September 2007. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ^ "Where can I go?". The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ "End of Cycle 2017 Data Resources DR4_001_03 Applications by provider". UCAS. UCAS. 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ "Sex, area background and ethnic group: E56 The University of Edinburgh". UCAS. UCAS. 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ "End of Cycle 2017 Data Resources DR4_001_02 Main scheme acceptances by provider". UCAS. UCAS. 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ "Top UK University League Table and Rankings". Complete University Guide.

- ^ "2017 entry UCAS Undergraduate reports by sex, area background, and ethnic group". UCAS. 8 January 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ McIvor, Jamie. "University offer rate for Scottish students falls". BBC News. BBC News. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "Scotland and EU tuition fee status admissions statistics" (PDF). University of Edinburgh.

- ^ "Rest of UK (England, Wales and Northern Ireland) tuition fee status admissions statistics" (PDF). University of Edinburgh.

- ^ "Overseas (Non-EU) tuition fee status admissions statistics" (PDF). University of Edinburgh. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ "Widening participation: UK Performance Indicators 2016/17". hesa.ac.uk. Higher Education Statistics Authority. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ "The University of Edinburgh Factsheet 2016/2017: Student Figures" (PDF). University of Edinburgh.

- ^ "University League Table 2021". The Complete University Guide. 1 June 2020.

- ^ "University league tables 2021". The Guardian. 5 September 2020.

- ^ "The Times and Sunday Times University Good University Guide 2021". Times Newspapers.

- ^ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2020". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2021". Quacquarelli Symonds Ltd.

- ^ "World University Rankings 2021". Times Higher Education.

- ^ "Research Excellence Framework (REF) 2014". The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ "World-leading research". 22 December 2011.

- ^ "The best UK universities chosen by major employers". Times Higher Education. London. 12 November 2015.

- ^ "A qualitative evaluation of non-educational barriers to the elite professions" (PDF). www.gov.uk. Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ^ "University ranking based on performance over 10 years" (PDF). The Times. London. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 April 2008. Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- ^ "Round University Rankings 2020". RUR Rankings Agency. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ https://www.scimagoir.com/rankings.php?sector=Higher%20educ

- ^ Turner, Camilla (9 August 2017). "Two of Britain's leading universities fall well below benchmark for student satisfaction, survey finds". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ "Edinburgh University worst for teaching". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ^ "Students give Edinburgh worst marks for teaching". The Times. London. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ^ "Students give Edinburgh worst marks for teaching". The Australian. 8 October 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ^ "Edinburgh University". The Times. London. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ "Good University Guide 2017". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 25 September 2016.

- ^ "University League Tables 2021". www.thecompleteuniversityguide.co.uk.

- ^ "University of Edinburgh - Complete University Guide". www.thecompleteuniversityguide.co.uk.

- ^ "Social Sciences". THE World University Rankings. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "The Students' Association". Ed.ac.uk. 31 August 2009. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ "Edinburgh festival news and reviews". The Guardian. London. 10 February 2008. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ "Fringe 2013 – Bedlam Theatre, Venue 49". Bedlamfringe.co.uk. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ "The Improverts – Edinburgh Fringe 2010 – British Comedy Guide". Comedy.co.uk. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ "Improverts | Edinburgh Festival Fringe". Edfringe.com. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ "Edinburgh University Savoy Opera Group". Eusog.org. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ "Theatre Paradok". Edinburgh University Students' Association. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ "Theatre Paradok". Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ www.lexlaw.co.uk, LEXLAW Solicitors & Barristers +44(0)207 1830 529. (3 September 2015). "The Journal Served with Winding-up Petition".

- ^ "Television Society (EUTV)". www.eusa.ed.ac.uk.

- ^ "World's oldest varsity match returns to Scotland". Herald Scotland. 19 May 2015.

- ^ "Royal Bank of Scotland Scottish Varsity Rugby Matches". University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- ^ "Edinburgh tops university medals table". The Daily Telegraph. London. 12 August 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ^ "EUSA democracy abolished in massive coup". The Journal (student newspaper). April 2012. Archived from the original on 20 April 2013.

- ^ "Edinburgh University Students' Association Societies". Eusa.ed.ac.uk. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ "Official Website of Edinburgh University Conservative and Unionist Association". Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ^ "Protest students occupy Edinburgh University hall". BBC News. 16 September 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ "Appleton Tower comes under occupation". The Student (newspaper). 17 December 2010. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ "Students disrupt royal visit in protest over tuition fees". STV News. 26 September 2011. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ "Student protesters at Edinburgh University are occupying a building". The Independent. 5 April 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ "Students vow to continue occupation over fossil fuels". www.edinburghnews.scotsman.com. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ "Security guard charged over student 'attack'". www.edinburghnews.scotsman.com. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- ^ "100 flats at £250 a month: Co-op housing project moves closer to goal". The Student Newspaper. 22 January 2014. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Hearty Squirrel Cooperative Edinburgh". Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ "What we do – The SHRUB Co-operative". Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Scotland Co-op List". students.coop. Students for Cooperation. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ "Edinburgh University Library". Britain in Print. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ^ "Omniana". University of Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 16 August 2005. Retrieved 14 January 2007.

- ^ "Graduation cap (Object Details)". University of Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 12 October 2006. Retrieved 14 January 2007.

- ^ Luscombe, Richard (25 June 2006). "One small step for John Knox, one giant leap for university". Scotland on Sunday. Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 14 January 2007.

- ^ "Honorary graduates database - The University of Edinburgh". University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ "Honorary graduates 2006/07". University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ a b "Honorary graduates 2017/18". University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ "Honorary graduates 2009/10". University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ "Honorary graduates 2007/08". University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ "Honorary graduates 2016/17". University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ "Honorary graduates 2015/16". University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ "Honorary graduates 2004/05". University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ "Honorary graduates 2004/05". University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ "Honorary graduates 2011/12". University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ "Honorary graduates 2010/11". University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ Schatzki, Stefan C. (2006). "Benjamin Waterhouse". American Journal of Roentgenology. 187 (2): 585. doi:10.2214/AJR.05.2125. PMID 16861568.

- ^ "Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online". Biographi.ca. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- ^ Cruess, Richard L. (26 November 2007). "Brief history of Medicine at McGill". Mcgill.ca. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- ^ Joseph Hanaway and Richard Cruess (8 March 1996). "McGill Medicine, Volume 1, 1829–1885". Mqup.mcgill.ca. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- ^ "School of Medicine: A Brief History, University of Pennsylvania University Archives". Archives.upenn.edu. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- ^ Lisa Rosner (1 April 1992). "Thistle on the Delaware: Edinburgh Medical Education and Philadelphia Practice, 1800–1825 — Soc Hist Med". Shm.oxfordjournals.org. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- ^ "Edinburgh and the USA". Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ^ "Edinburgh's Links to the USA". Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ^ Bennett, Brett; Kruger, Fred (11 November 2015). Forestry and Water Conservation in South Africa: History, Science and Policy. ANU Press, 2015. ISBN 9781925022841.

Further reading[edit]

- Horn, D. B. (1967). A Short History of the University of Edinburgh: 1556–1889.

- Grant, Alexander (1884). The Story of the University of Edinburgh. London.

- Dalzel, Andrew (1862). History of the University of Edinburgh. Edmonston and Douglas.

- Robert D. Anderson; Michael Lynch; Nicholas T. Phillipson (2003). University of Edinburgh: an illustrated history. Edinburgh University Press.

- Nick Haynes; Clive B. Fenton (2017). Building Knowledge: An Architectural History of the University of Edinburgh. Historic Environment Scotland. ISBN 9781849172462.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to University of Edinburgh. |